The magazine that went on to become Conservation Land Management (CLM) first went to print in the spring of 1993. At this time it was named enact, and was published by English Nature (the predecessor of Natural England). The aim then was to promote land management for nature conservation and provide easy-to-understand advice on useful techniques – an objective that CLM still stands by today, but now covering a much wider variety of conservation issues. Here, Assistant Editor Catherine Mitson highlights the key articles of the latest Spring 2021 issue.

The UK’s departure from the EU offers a number of opportunities for the environment, and in particular for the future of farming in the UK. And so, agricultural policy is undergoing a reform and a new payment scheme, the Environmental Land Management scheme (ELM), has been introduced to England.

ELM will pay farmers based on the public goods they provide, such as habitat restoration or flood management, as a means of contributing to the government’s 25 Year Environment Plan. But is ELM up to the task of delivering its aim? In this issue Alice Groom, RSPB’s senior policy officer, provides an up to date overview of what we know about ELM so far, the proposed timeline of the seven-year agricultural transition period, and, importantly, highlights the pitfalls and challenges that need to be addressed in order for ELM to be a success.

Staying within the theme of farming, exciting new approaches are being trialled in the The Great Fen, which stretches between Huntingdon and Peterborough, and is undergoing landscape-wide restoration to improve the sustainability of the fens for both people and wildlife. Within this vision, the Great Fen team are in the midst of the three-year Water Works project that is focused on a ‘wet farming’ approach. Wet farming is a type of agriculture on wetter soils, a much more suited approach for the natural conditions of the fens; this will help to protect peat, lock in carbon, support wildlife and provide local farmers with new economic opportunities.

Staying within the theme of farming, exciting new approaches are being trialled in the The Great Fen, which stretches between Huntingdon and Peterborough, and is undergoing landscape-wide restoration to improve the sustainability of the fens for both people and wildlife. Within this vision, the Great Fen team are in the midst of the three-year Water Works project that is focused on a ‘wet farming’ approach. Wet farming is a type of agriculture on wetter soils, a much more suited approach for the natural conditions of the fens; this will help to protect peat, lock in carbon, support wildlife and provide local farmers with new economic opportunities.

Novel crops, such as gypsywort, bulrush, sphagnum moss and watercress, chosen for their potential uses for food, flavourings and medicine, are currently being trailed in specially prepared planting beds. Data is simultaneously being collected to measure the rate of carbon capture and loss in these trial plots – it is hoped that not only will carbon loss be reduced within the Great Fen, but also that these changes in fenland agriculture will help sequester carbon too.

Ribble Rivers Trust (RRT) also seeks to improve the condition of existing habitats, and uses an evidence-based approach to target land management where it will have the biggest benefits for wildlife, people, and the environment. Focused in the Ribble catchment in north-west England, Ellie Brown, GIS data and evidence officer at RRT, demonstrates how the use of mapping and data analysis has helped the charity to identify key areas for conservation projects.

One example of this has been along Bashall Brook. Using solar radiation maps RRT identified a particular stretch of the watercourse that was at risk of overheating. The main reason behind the increase in water temperature in this area was a lack of surrounding vegetation providing enough shade, and so it was decided to create a woodland running along either side of the bank. RRT is conscious to only ever plant trees where it is appropriate, and the resulting vegetation has helped to create much-needed shade along the brook.

In some circumstances all it takes is just a handful of people in a local community with a shared passion to come together to make a difference. In 1970 the Bristol section of the M5 motorway was opened and, during this work, a particular stretch of St George’s Hill had the topsoil removed from the roadside verge. Giles Morris, a conservation volunteer with St. George’s Flower Bank, describes how a dedicated team of volunteers from the local villages worked together to clear the encroaching scrub on this verge, and how this led to the establishment of a species-rich grassland. This on-going management project has been a huge success, and the site has since been declared a Local Nature Reserve.

In some circumstances all it takes is just a handful of people in a local community with a shared passion to come together to make a difference. In 1970 the Bristol section of the M5 motorway was opened and, during this work, a particular stretch of St George’s Hill had the topsoil removed from the roadside verge. Giles Morris, a conservation volunteer with St. George’s Flower Bank, describes how a dedicated team of volunteers from the local villages worked together to clear the encroaching scrub on this verge, and how this led to the establishment of a species-rich grassland. This on-going management project has been a huge success, and the site has since been declared a Local Nature Reserve.

Conservation success stories, such as that of St George’s Flower Bank, make for an inspirational read. And staying on a positive note, beavers are certainly grabbing the attention of many in recent years and have been reintroduced to a number of different sites across the UK. For our Introducing feature it was a delight to have Eva Bishop discuss how the Beaver Trust came to be, what it is trying to achieve, and the exciting projects it has been involved in.

In every issue you can expect to see Briefing and On the ground, but other features that regularly appear include Viewpoint, a similar length to our main articles, but here authors can voice their own views on various conservation issues; Introducing, a feature focused on organisations involved in conservation, and here they can discuss their aim and describe specific conservation projects they are involved in; and Review, which can include letters from readers or updates from our authors.

In every issue you can expect to see Briefing and On the ground, but other features that regularly appear include Viewpoint, a similar length to our main articles, but here authors can voice their own views on various conservation issues; Introducing, a feature focused on organisations involved in conservation, and here they can discuss their aim and describe specific conservation projects they are involved in; and Review, which can include letters from readers or updates from our authors.

CLM is published four times a year in March, June, September and December, and is available by subscription only, delivered straight to your door. Subscriptions start from £22 per year. Previous back issues are also available to purchase individually (subject to availability).

If you are involved in a conservation project and think your experiences could be useful to other practitioners, we would love to hear from you. If you are interested in writing for CLM feel free to contact us – we will be happy to discuss your ideas with you.

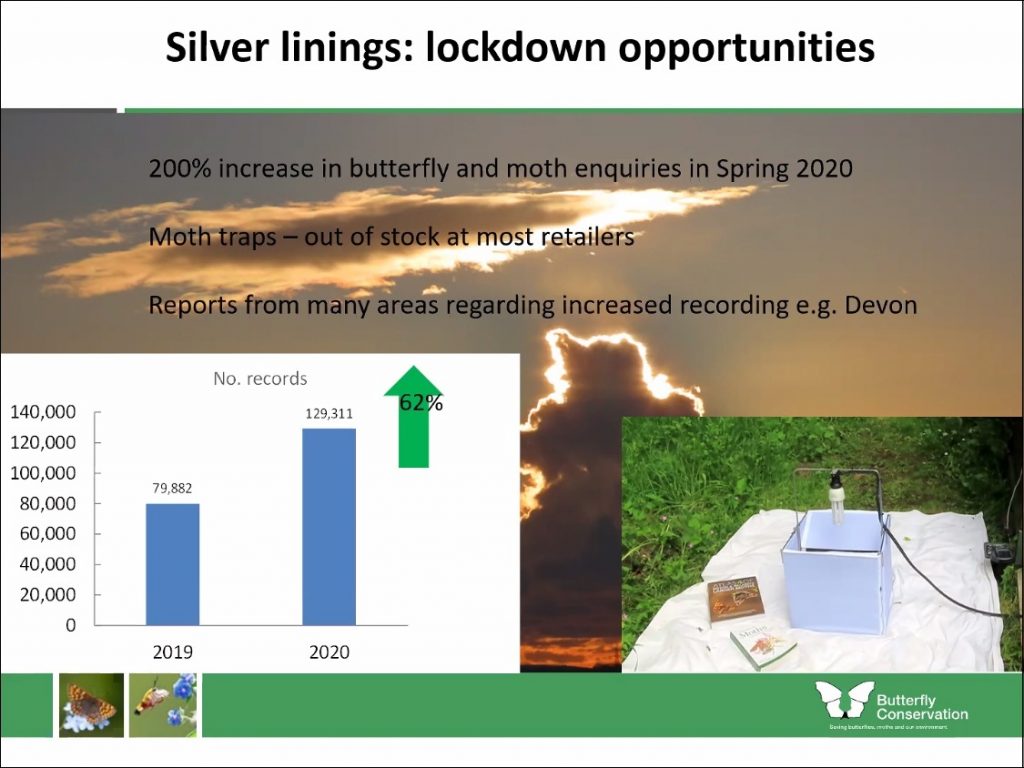

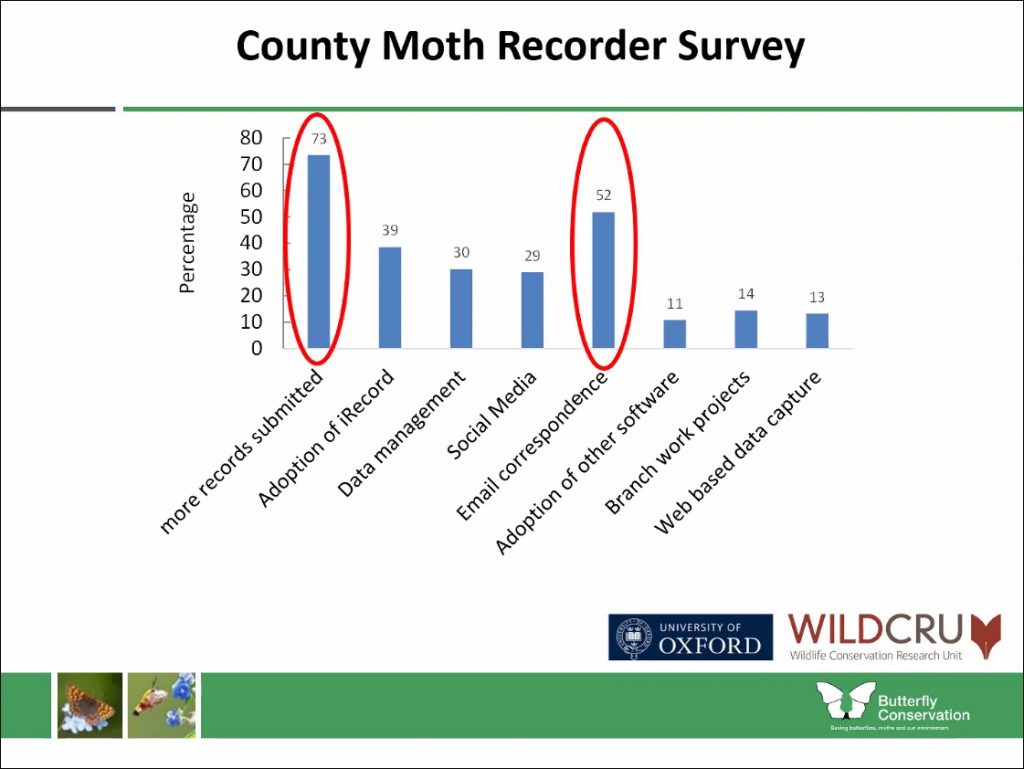

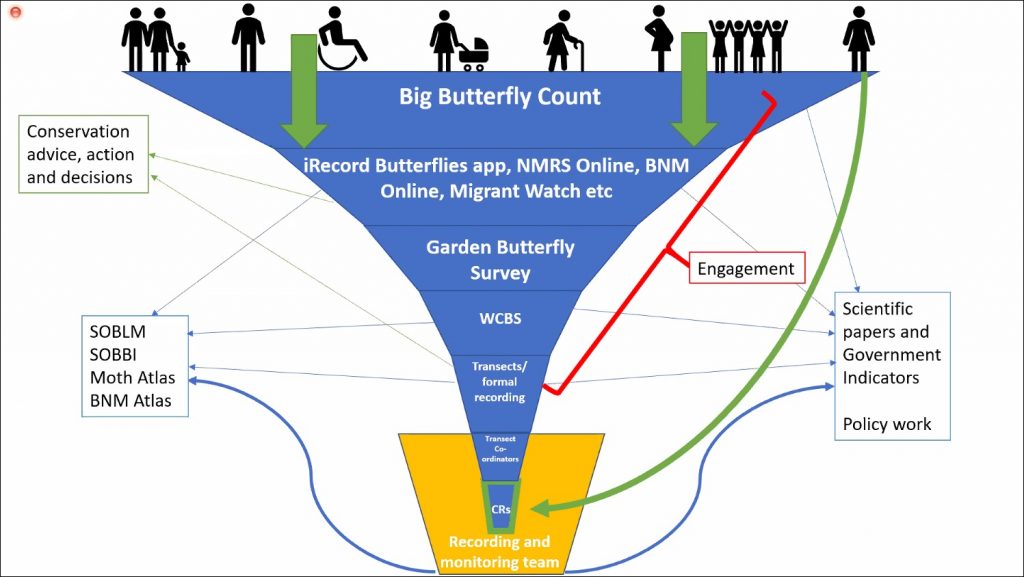

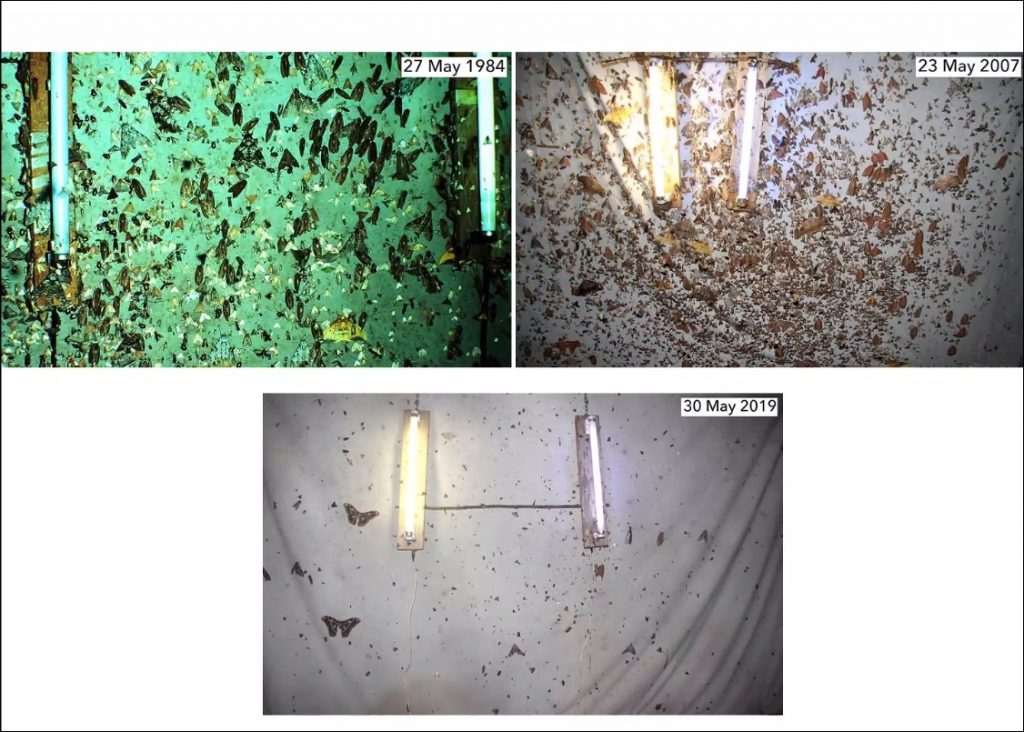

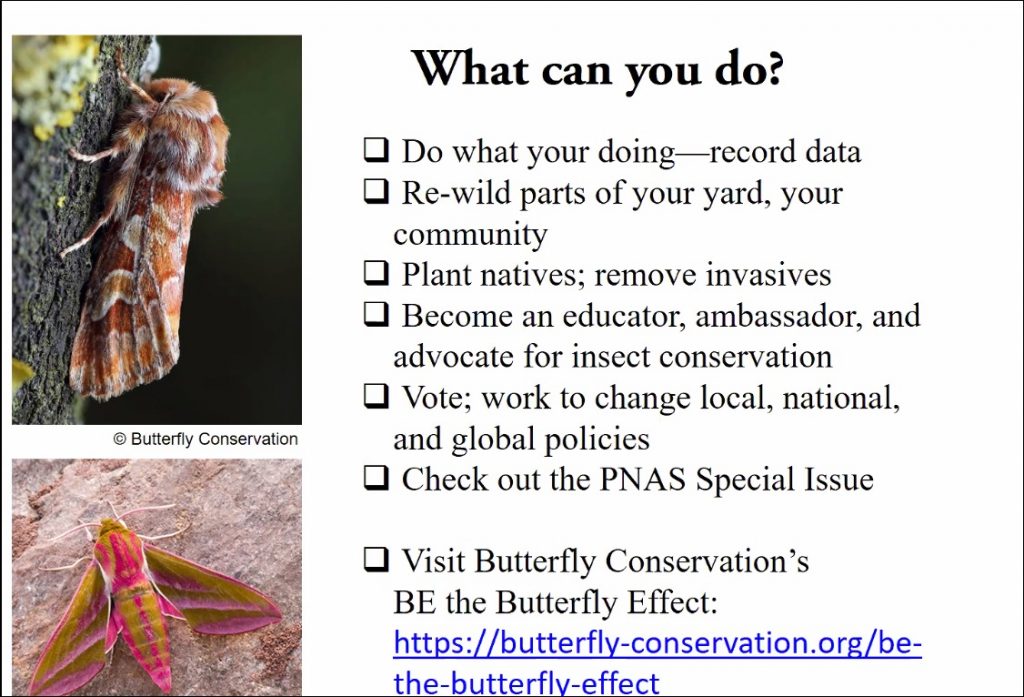

Katie spoke about the benefits of this widening pool of public participation suggesting that, not only does it expand our understanding of national biodiversity, but it also connects us meaningfully with wildlife and has positive effects on our own personal wellbeing. Public perception of moths and butterflies is improving through events like Butterfly Conservation’s Big Butterfly Count, which encourages people to log the species they see in their local patch for a set period of time using a dedicated app. The wealth of sightings that come through apps like this and iRecord – alongside information gathered from social media and anecdotal sources – has meant that the recording process is a vast and time consuming activity for volunteers. Katie spoke on how this process currently works and speculated on how it might be streamlined moving forwards.

Katie spoke about the benefits of this widening pool of public participation suggesting that, not only does it expand our understanding of national biodiversity, but it also connects us meaningfully with wildlife and has positive effects on our own personal wellbeing. Public perception of moths and butterflies is improving through events like Butterfly Conservation’s Big Butterfly Count, which encourages people to log the species they see in their local patch for a set period of time using a dedicated app. The wealth of sightings that come through apps like this and iRecord – alongside information gathered from social media and anecdotal sources – has meant that the recording process is a vast and time consuming activity for volunteers. Katie spoke on how this process currently works and speculated on how it might be streamlined moving forwards.

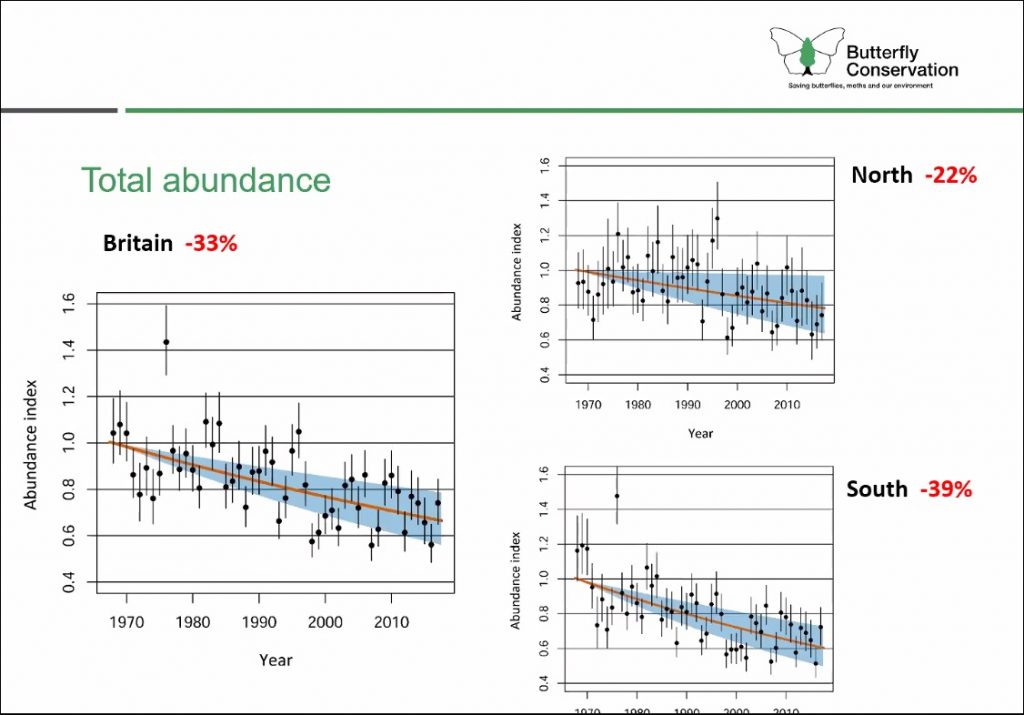

The compilation of data for the new

The compilation of data for the new

We joined the session on thermal imaging run by Dr Kayleigh Fawcett Williams to learn more about how this equipment is being used in ecological consultancy. Most participants were new to thermal imagery, so Dr Fawcett Williams walked us through the basics. She explained that thermal imaging works by picking up thermoelectrics from the environment – infrared radiation, meaning that it is not at all invasive to the animals as the scopes emit no light (as opposed to night vision cameras that use infrared to light up the subjects).

We joined the session on thermal imaging run by Dr Kayleigh Fawcett Williams to learn more about how this equipment is being used in ecological consultancy. Most participants were new to thermal imagery, so Dr Fawcett Williams walked us through the basics. She explained that thermal imaging works by picking up thermoelectrics from the environment – infrared radiation, meaning that it is not at all invasive to the animals as the scopes emit no light (as opposed to night vision cameras that use infrared to light up the subjects). The benefits of this survey method were explained, including: ability to use at all times of day and for long durations and cost effectiveness due to lack of man power needed. Thermal imaging can reduce the risk of false positives when it comes to identification of species and also provide a wider picture of landscape or infrastructure use by illustrating patterns of activity. She also highlighted that it is good for multidisciplinary work (e.g. for firms that work with engineers) as it has a range of applications that are not just ecology based.

The benefits of this survey method were explained, including: ability to use at all times of day and for long durations and cost effectiveness due to lack of man power needed. Thermal imaging can reduce the risk of false positives when it comes to identification of species and also provide a wider picture of landscape or infrastructure use by illustrating patterns of activity. She also highlighted that it is good for multidisciplinary work (e.g. for firms that work with engineers) as it has a range of applications that are not just ecology based. She explained that bats are protected by law and that while only licensed individuals should be in contact with bats, first aid is considered emergency care and so this can be administered without a license. That being said, you will need to be able to justify any contact you have had with a bat so she strongly suggested that you keep records of the encounter.

She explained that bats are protected by law and that while only licensed individuals should be in contact with bats, first aid is considered emergency care and so this can be administered without a license. That being said, you will need to be able to justify any contact you have had with a bat so she strongly suggested that you keep records of the encounter.

Over the coming months, British Wildlife will be exploring the many facets of rewilding as they relate to conservation in Britain through a new series, ‘Wilding for Conservation’, a title which, we hope, captures the wide range of approaches to letting nature take back control. We start things off in

Over the coming months, British Wildlife will be exploring the many facets of rewilding as they relate to conservation in Britain through a new series, ‘Wilding for Conservation’, a title which, we hope, captures the wide range of approaches to letting nature take back control. We start things off in