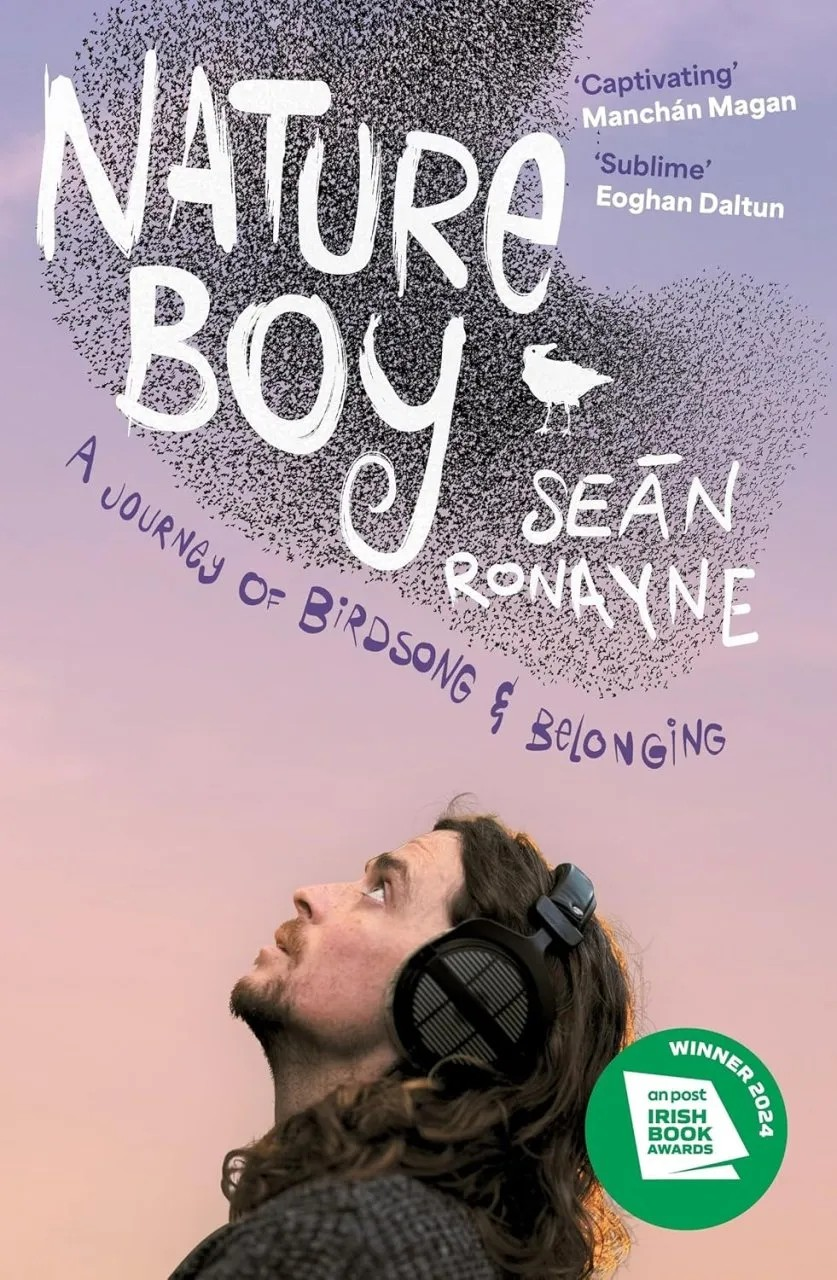

An inspiring story of love, connection and the healing power of nature, author Seán Ronayne recounts his journey to record all the regularly occurring species of birds in Ireland. He also tells the stories of his adventures across the Sahara Desert, the jungles of Nepal, and the streets of Thailand, revealing the wonders of the natural world.

An inspiring story of love, connection and the healing power of nature, author Seán Ronayne recounts his journey to record all the regularly occurring species of birds in Ireland. He also tells the stories of his adventures across the Sahara Desert, the jungles of Nepal, and the streets of Thailand, revealing the wonders of the natural world.

Seán Ronayne is an ornithologist and naturalist who was born in Cork, Ireland. He spent his childhood exploring the fields and woodlands around his hometown, before studying Zoology at University College Cork, followed by a Master’s in Marine Biology. He secured his first ornithology role in 2017, before relocating to Barcelona with his partner where he began recording local wildlife and birds in earnest. Upon their return to Ireland in 2020, Seán embarked on a project to record all of Ireland’s birds, some of which are on the cusp of extinction, and he now has only three species left to record.

We recently had the opportunity to speak to Seán about Nature Boy, including what first sparked his interest in nature, which equipment he uses for sound recording and more.

In your book, you talk about how nature has been a constant source of comfort and curiosity for you. Do you remember when the natural world first began to resonate with you? Was there a key event which sparked your interest?

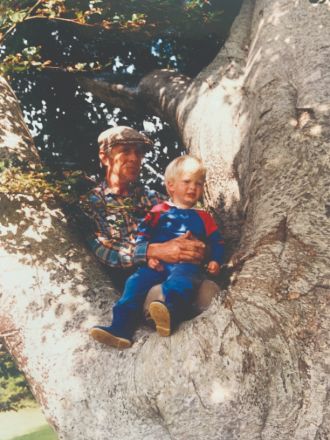

Yes! I have two standout moments, both of which are particularly special in different ways. I was a very active child, and I really mean that. I was always on the go, and if I couldn’t be on the go, I was wriggling, squirming, and crying – longing to be free. My father quickly learned that a foray into nature was the cure. He would take me to our local nature reserve and imitate the sounds of all the wildlife around us. I would belly laugh at his attempts and give him my best guess. It was a great game to me, but it was also an education in disguise – Dad was teaching me to listen to nature, and to get to know my neighbours by ear.

The other is my first memory of a bird. I was very young, around 2 years old off the top of my head, and the bird was pointed out to me by my Dad’s father – Pops. He loved birds too. I’ll never forget that first view of a magpie, with its regal pied plumage, draping long tail, and green and purple shimmying iridescence. Pops died not long after. I did not understand, but today, every time I see a magpie I see Pops, smile and thank him for the journey he sent me on.

Can you share with us what equipment you use for recording and what your decision process was for selecting it?

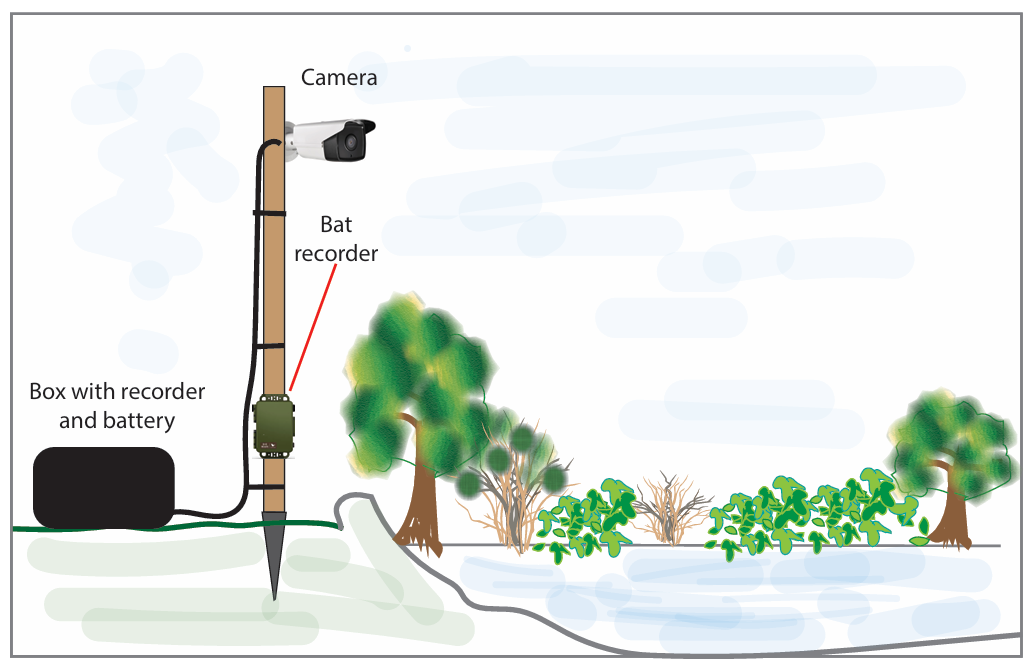

I am not a technical sound-recordist. I follow my ears, and my heart, and then I record the sounds that call to me with whatever tools I have at my disposal. I learned my skills through trial and error (mostly through error), but you know the phrase – even a broken-down clock is right twice a day! For isolating birds and getting a close intricate recording, I use a Dodotronic Hi-Sound parabolic reflector, paired with a second-hand Olympus LS-12 recorder – the Nokia 3210 of the sound recording world. To capture really intimate moments, or for longer, all weather deployments, I used a Song Meter Mini II. The sound is superb, and the device can be hidden easily, allowing birds to approach close and whisper into the mics unbeknownst to themselves. This provides intimate chitter-chatter I’d never otherwise get the opportunity to capture, and the Song Meter runs for weeks and can survive all manner of weather conditions! I guess these two pieces are my go-to tools.

Bioacoustics is one of the fastest-growing industries in the ecological sector. Are there any technological advances you’d like to see in this field?

I am really happy with where it’s at, to be honest! I can see that AI software to auto-identify birds is being worked on, but I don’t really care for that. I absolutely adore pouring through raw audio with a fine-tooth comb myself. In doing so, I enter that world, and I learn so much – a fast summary response kills the magic and learning for me. Perhaps others will disagree with me, but for my needs I am happy with where the technology is at, and the constant need for ‘progress’ in today’s world has a lot to answer for in terms of ecological, climate, and planetary degradation, after all.

While watching your documentary, I was very moved by your recording of the last known pair of Ring Ouzels in Ireland. Can you describe what it felt like to capture that moment, knowing you were recording a piece of history?

It was utterly devastating, and highly stressful. We’re talking about a bird that has been visiting our uplands each summer for hundreds, even thousands of years, wiped out in a heartbeat, with the majority of people not even knowing it existed at all. The stress came into the equation because I felt a strong desire, responsibility even, to capture its voice to show people the sonic beauty of what we are erasing, and what we need to stand up and fight for. With just one known pair remaining I was unsure if I had time to give this bird a voice, and if I didn’t capture it I’d have been doubly devastated – I’d have felt like I left it down, leaving it to die out in silence, unheard and forgotten. That did not happen though, at least.

Birdsong seems to have the ability to engage and move people in a way that perhaps other facets of nature don’t. Why do you think this is?

Well, I think it’s hard not to love it, isn’t it? Birdsong is nature’s melody! The dawn chorus is nature’s orchestra. It’s always there, it’s such a treat to listen to and it’s completely free. We have evolved in tandem with it. We hear birdsong, and everything is right with the world…we don’t hear birdsong, and something has gone terribly wrong. Right? A forest has been felled, a river has been covered, a bog has been drained, a city has enveloped, a motorway has drowned it out.

In your book, you talk about the importance you placed on your first bird ID guide as a child. Do you have any go-to books for bird identification?

This is easy – the Collins Bird Guide (the bible), and of course the legendary Sound Approach collection.

With your recent book, tour and documentary, you’ve made a real push to engage with the public and remind them of the natural world. What do you hope people take from your work?

I just hope that people realise how inexplicably beautiful, educational, nourishing, wondrous, and ever-giving nature is. But I also need them to know that it’s in freefall. Because of our own very actions. And inactions. My work is a call to arms, with hope and beauty being my primary weapons – with a brief but sharp slap of loss and despair. The latter is necessary, but it is my secondary weapon. Love and hope outgun loss and despair always.

You currently only have 3 species left to record to complete your mission to record every Irish bird. Do you have any plans for afterwards?

Of course. I will be on this journey for as long as I’m gifted time on this earth. Recording all of these birds was never intended to be a tick and run exercise. Every time I listen to a given species or individual I learn something new. I capture a new voice. The more I listen, the more I realise how little I know. And that’s gorgeous, isn’t it!? This is what I mean when I say that nature is ever-giving. And to answer you in more direct terms, I fully intend to write more, and to work on more film projects. I’ll also tour my talks, stories and sounds until people have had enough of me, which I hope never happens (haha)!

Nature Boy: A Memoir of Birdsong and Belonging by Seán Ronayne is published by Hachette Books Ireland in Trade Paperback and is available from nhbs here.

Nature Boy: A Memoir of Birdsong and Belonging by Seán Ronayne is published by Hachette Books Ireland in Trade Paperback and is available from nhbs here.

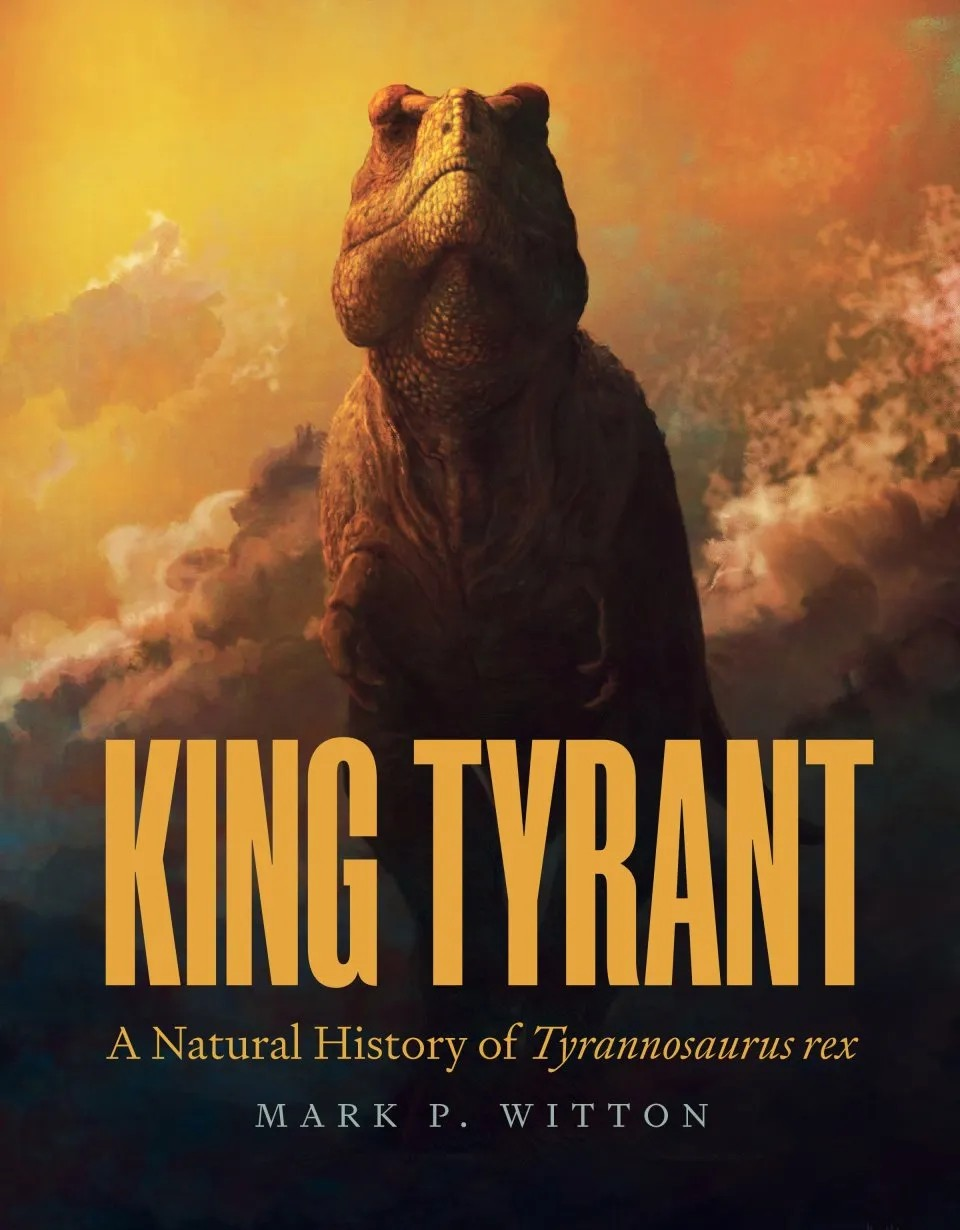

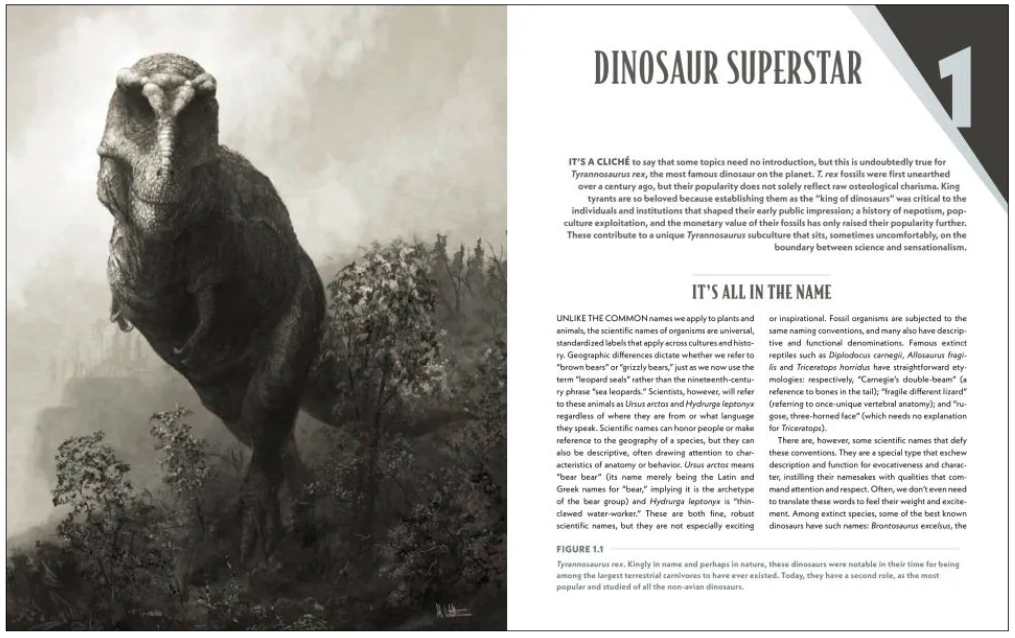

Given how frequently the name T. rex crops up, you might even get a bit annoyed: not you again! All the more reason to read this book. Witton is acutely aware that a veritable subculture has grown up around this one species that “sits, sometimes uncomfortably, on the boundary between science and sensationalism” (p. 1). These popular depictions, often carrying with them an air of scientific authority, bleed into people’s consciousness, creating something less of a dinosaur and more of a chimaera, with traits both exaggerated and fictional. One of Witton’s most important goals with King Tyrant is to “deconstruct hype and controversy” (p. 41). The first chapter daringly combines a précis of the first century of research with an examination of the sociological side. How did this particular species become palaeontology’s rock star? It is a fascinating history that starts at the American Museum of Natural History who promoted it to attract large crowds. It was “proverbial lightning in a bottle” (p. 278), with an influential legacy that lasts to this day in movies, documentaries, and merchandise. And yet, popular depictions “have nothing on what science tells us about the reality of Tyrannosaurus rex” (p. 279).

Given how frequently the name T. rex crops up, you might even get a bit annoyed: not you again! All the more reason to read this book. Witton is acutely aware that a veritable subculture has grown up around this one species that “sits, sometimes uncomfortably, on the boundary between science and sensationalism” (p. 1). These popular depictions, often carrying with them an air of scientific authority, bleed into people’s consciousness, creating something less of a dinosaur and more of a chimaera, with traits both exaggerated and fictional. One of Witton’s most important goals with King Tyrant is to “deconstruct hype and controversy” (p. 41). The first chapter daringly combines a précis of the first century of research with an examination of the sociological side. How did this particular species become palaeontology’s rock star? It is a fascinating history that starts at the American Museum of Natural History who promoted it to attract large crowds. It was “proverbial lightning in a bottle” (p. 278), with an influential legacy that lasts to this day in movies, documentaries, and merchandise. And yet, popular depictions “have nothing on what science tells us about the reality of Tyrannosaurus rex” (p. 279). T. rex, more than any other species, attracts a lot of fringe ideas from inside and outside of academia, and Witton leaves no rock unturned. On the one hand, there are the minority views and “non-troversies” (thanks Witton, I am stealing that brilliant term) that get far too much airtime, such as the existence (or not) of a dwarf species, “Nanotyrannus“, or the scavenging hypothesis, the notion that T. rex was a scavenger rather than a hunter. Needless to say, neither idea curries much favour among professionals. On the other hand, actual scientific debates are often ignored by the press. Opinions are divided on whether dinosaurs were already on their way out before the asteroid impact or were still in their prime. Witton provides the best overview of this topic that I have read so far.

T. rex, more than any other species, attracts a lot of fringe ideas from inside and outside of academia, and Witton leaves no rock unturned. On the one hand, there are the minority views and “non-troversies” (thanks Witton, I am stealing that brilliant term) that get far too much airtime, such as the existence (or not) of a dwarf species, “Nanotyrannus“, or the scavenging hypothesis, the notion that T. rex was a scavenger rather than a hunter. Needless to say, neither idea curries much favour among professionals. On the other hand, actual scientific debates are often ignored by the press. Opinions are divided on whether dinosaurs were already on their way out before the asteroid impact or were still in their prime. Witton provides the best overview of this topic that I have read so far.

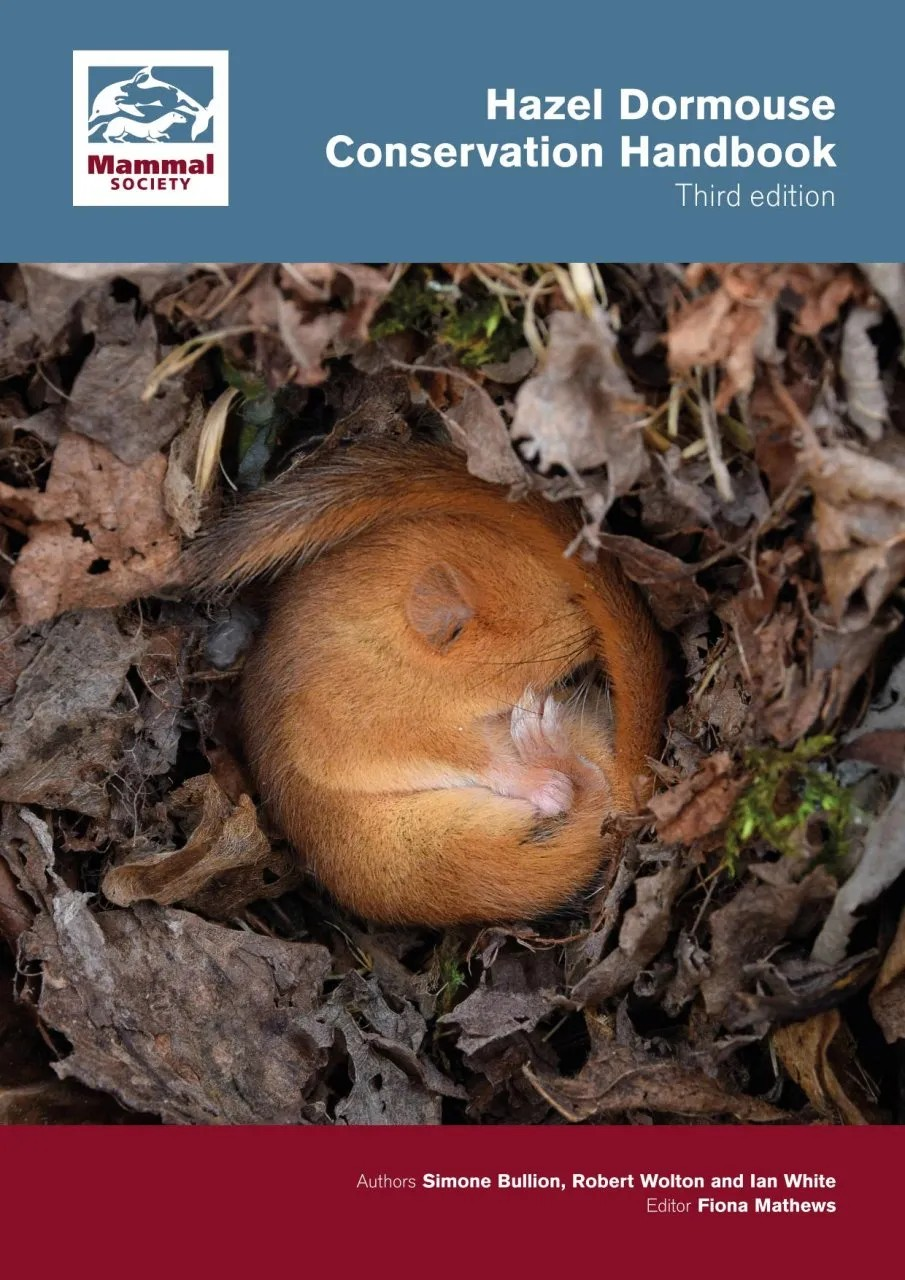

Flemming Ulf-Hansen is an ecologist with nearly 37 years of experience working in wildlife conservation, primarily across Exmoor and Salisbury Plain. He is the founding chair of the Exmoor Mires Project and specializes in ecological restoration, with a host of expertise in grassland, woodland, and heathland management, as well as invasive species control. He joined the Nature Conservancy Council in 1988 and was awarded a Churchill Fellowship in 2010 to study habitat restoration.

Flemming Ulf-Hansen is an ecologist with nearly 37 years of experience working in wildlife conservation, primarily across Exmoor and Salisbury Plain. He is the founding chair of the Exmoor Mires Project and specializes in ecological restoration, with a host of expertise in grassland, woodland, and heathland management, as well as invasive species control. He joined the Nature Conservancy Council in 1988 and was awarded a Churchill Fellowship in 2010 to study habitat restoration.

Susan Young is a photographer and writer based in South Devon, who has a wealth of experience in wildlife photography. She has authored several books, including

Susan Young is a photographer and writer based in South Devon, who has a wealth of experience in wildlife photography. She has authored several books, including