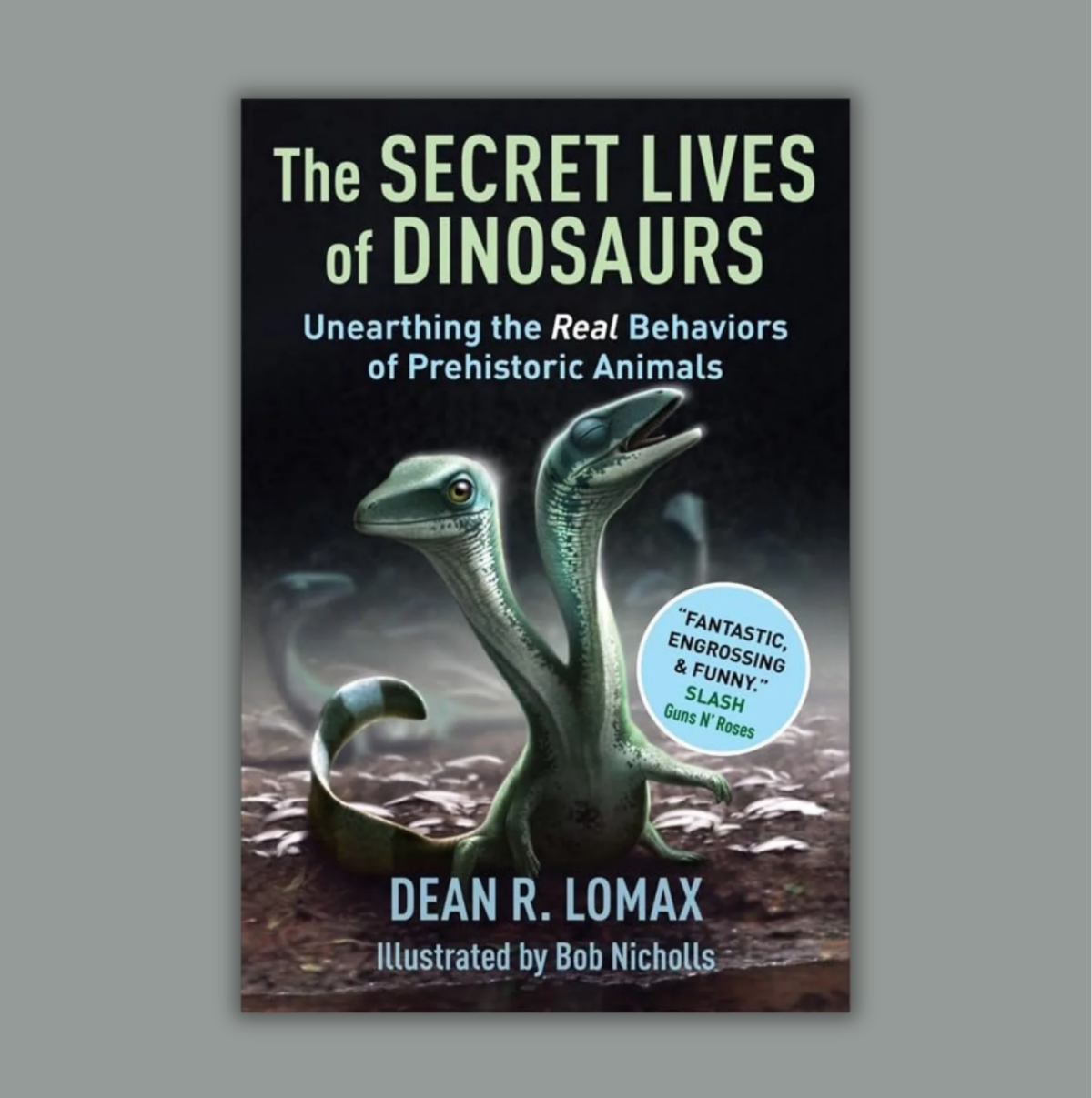

Back in 2021, palaeontologist Dean Lomax impressed me with Locked in Time, a popular science book that looked at the behaviour of extinct animals as revealed by a selection of extraordinary fossils. Showing that there is more to be said on the topic, he now returns with The Secret Lives of Dinosaurs, which features another tranche of remarkable fossils. More than just a sequel, this book improves on its predecessor in several respects.

Since the publication of Locked in Time, there have been several other popular books on trace fossils and the behaviour of extinct animals. I reviewed Michael J. Benton’s introductory guide Dinosaur Behavior and David Hone’s excellent Uncovering Dinosaur Behavior, while Jean Le Loeuff’s What Did Dinosaurs Think About? is on my radar. Anthony J. Martin, whose 2014 book on trace fossils, Dinosaurs Without Bones, merits mention in this context, returned in 2023 with Life Sculpted to look at trace fossils of bioerosion. Collectively, these books show what else you can do with this topic, so I was curious to see what tack Lomax would take this time.

Undeniably, The Secret Lives of Dinosaurs has all the appearances of being Locked in Time II. It follows the same formula: previously, we got 50 case studies under five subject headings; now we get another 49 case studies under eleven headings. Furthermore, in his introduction, Lomax adds that “You might even consider this a sort of sequel” (p. 1). Finally, when I interviewed Lomax back in 2021, he mentioned originally wanting to discuss 100 fossils but having to cut his selection in half. One fossil he regretted having to omit was the arthropod Aquilonifer spinosus, nicknamed the kite runner, that was found with its offspring tethered to its body by long filaments. That fossil here appears in chapter 3 as “Tethered Toddlers”. However, calling this book a mere sequel would be doing it a disservice: this is more than a compilation of the leftovers that missed the cut last time.

For starters, we can establish that the three strong points I highlighted last time are all still in effect. First, Lomax reiterates that not all interpretations of certain behaviours are uncontested. Though we have interesting evidence of swimming tracks made by small theropods, sauropod swimming tracks are more controversial, while palaeontologists continue to discuss whether the rocks swallowed by marine reptiles (gastroliths) acted as ballast or digestive aids. Second, Lomax continues to shine a light on the inner workings of palaeontology. When an excavator bucket cuts right through an elasmosaur fossil, he brushes this aside with a casual “These things happen” (p. 240). Several case studies show how certain fossil discoveries play out over decades of intermittent study and attempts to relocate historic dig sites. Third, Lomax continues to mix entertaining popular science writing that has lost none of its enthusiasm with gentle education. He still defines terminology on first use and continues to stress the relevance of studying animal behaviour today to understand animals of the past.

More importantly, The Secret Lives of Dinosaurs improves on its predecessor in several respects, most noticeably in its lush presentation. The publisher has thrown its full weight behind this book, printing it in colour on thicker paper stock. It is thus noticeably heavier than Locked in Time, even after accounting for its extra 54 pages. Bob Nicholls’s excellent artwork—and there is a lot of it—really pops this time around, while the numerous photos and illustrations of fossils are crisp and informative. One outstanding example of how this is put to good use is the section on the fossil evidence for caudal autotomy, i.e. the voluntary amputation of one’s tail, shown by many small reptiles today as a defence against predators. Page 117 shows two colour photos of a lizard fossil under visible and UV light, the latter revealing a regenerated, cartilaginous tail invisible to the naked eye. Another change is that all entries are slightly longer, increasing from an average of 4–5 pages to 5–7 pages. On several occasions, Lomax uses this to detail the chain of reasoning by which scientists eliminate competing explanations to arrive at their conclusions. How do you tell apart stomach contents from fossil embryos when a species is a known cannibal? Have we found evidence of ammonite eggs, or did another cephalopod repurpose empty ammonite shells? And how do you conclude that a combined trackway is evidence of two giant millipedes mating?

Finally, I think that more of the same, when done well, is not a bad thing. On that note, Lomax has again curated a collection of truly exceptional fossils. Though at least two case studies were discussed in Uncovering Dinosaur Behavior and that giant Tyrannosaurus rex turd featured in King Tyrant, much here was new to me. Never mind the title, this is about much more than just dinosaurs. Lomax jokes how one of the best ways of surviving in the fossil record is being eaten, as evidenced by descriptions of a new lizard and a new beetle species from respectively Microraptor stomach contents and coprolites from (likely) Silesaurus. And while the present often informs the past, sometimes the past reveals something about biology today, such as the discovery of an amber-encased fossil of a tiny springtail hitching a ride on a mayfly. Conventional wisdom had it that springtails spread via oceanic currents or aerial plankton; now we can add phoresy (the act of attaching oneself to a host organism to catch a free ride) to that list. Or take the footprint on a coprolite, showing that crocodilians, too, sometimes stepped in it. Or the scars on a plant leaf that, according to one team of researchers, exactly match those made by zombified ants today when they clamp their jaws down on a leaf vein just before dying and sprouting a fungus from their head. Yep, an unusual example of fossilised evidence of ant-fungal parasitism! It is hard to pick favourites with such a remarkable list of fossils.

How Lomax got Slash from Guns N’ Roses (!) to provide a blurb for the book? I am sure there is an interesting story here, but his praise, placed prominently on the cover, is one that I can echo. If you liked Locked in Time, this book is a no-brainer, improving on the execution of the concept. If you would like a novel kind of popular palaeontology book, whether for yourself or for somebody else, this book also comes highly recommended.

Sverker Sörlin is an author, historian, and science communicator. He is currently Professor of Environmental History at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

Sverker Sörlin is an author, historian, and science communicator. He is currently Professor of Environmental History at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.