Throughout May 2022 Plantlife have once again made their impassioned annual plea for garden owners across the UK to resist the urge to mow lawns and tidy up their gardens and to join in with #NoMowMay. It’s a simple enough premise to leave grassy areas alone for a month, and it has huge benefits for biodiversity at this time of year to do so, giving a wide variety of flowering plants a chance to bloom early in appeal to our rich network of vital pollinators.

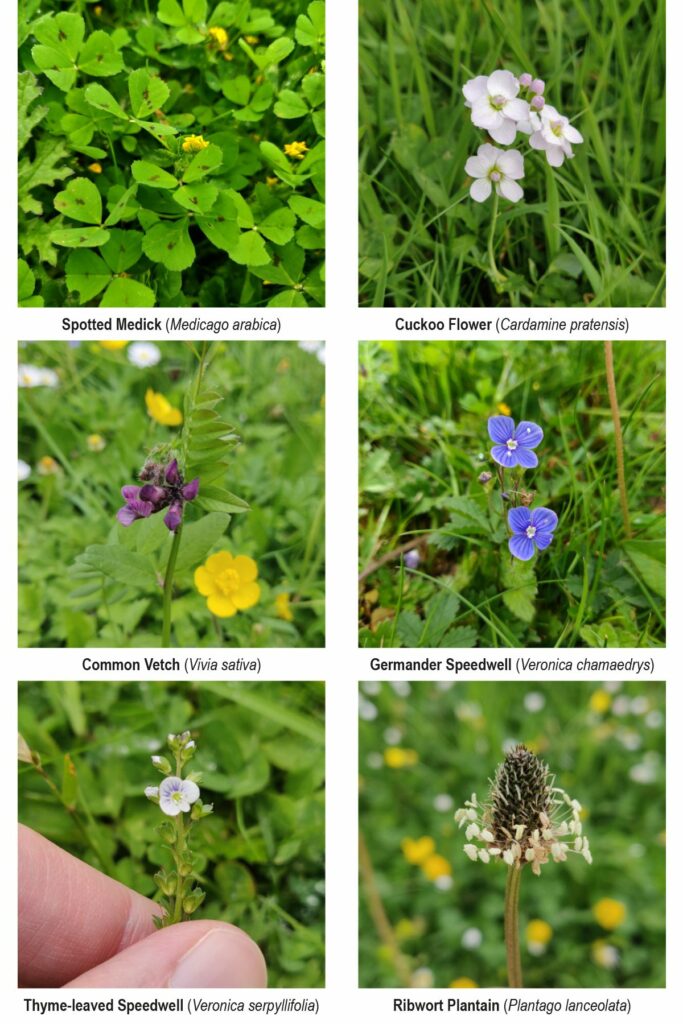

As in 2021, we here at NHBS have participated this year by letting the grassy areas on our premises flower and the results were quickly quite astounding. Within days there was a carpet of daisies and dandelions, Germander Speedwell and Black and Spotted Medic, and, as the month progressed and we explored further, the picture grew more and more complex. Tangles of Common Vetch, Creeping Buttercup and Common Mouse-ear proliferated, and tall fronds of Beaked Hawk’s Beard, Ribwort Plantain and Prickly Sow-thistle appeared. Hidden deep within a mixed mat of grasses the miniscule flowers of Cut-leaved Crane’s-bill, Thyme-leaved Speedwell and Scarlet Pimpernel flourished and, at the lawn edges, tall stands of Garlic Mustard and Cleavers towered over the last of the seasons Bluebell flowers.

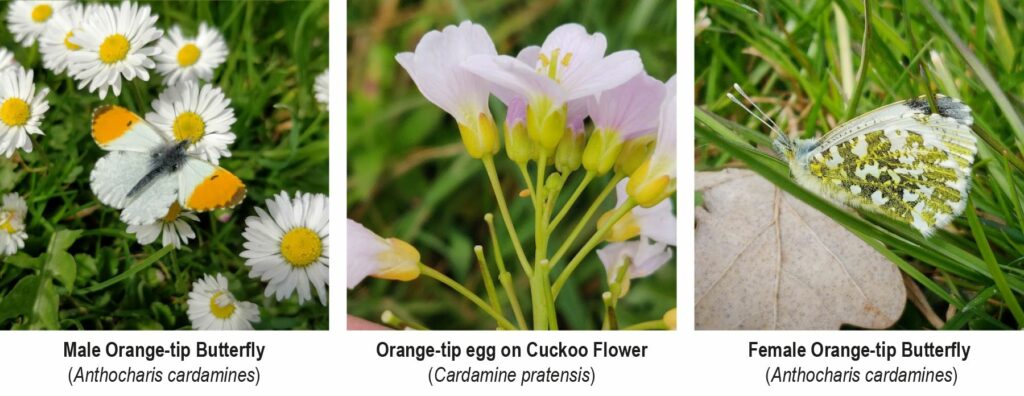

It can still feel strangely radical to let an area of public space, or even a private garden, to grow wild. Perhaps it can feel like going against the flow to sit back and not mow or trim the grass, and to embrace a modicum of wild chaos. Much of our wildlife relies on the flowering plants that we suppress with our tidiness and our control of lawns. Multitudes of beetles, bees, ants, moths and butterflies have evolved alongside plants that, given half a chance, can still thrive in our green spaces. No Mow May offers us a glimpse into this rich relationship, this conversation in time, and it provides a lifeline. One flower that showed up in our lawn here, by way of an example, is the Cuckoo flower or Lady’s Smock, a light and elegant pink flower of grasslands that is almost exclusively selected by the Orange-tip (and Green-veined White) butterfly in spring to lay their eggs on, as it feeds the caterpillars when they hatch. Growing up to 50cm in height its reach is well within the mowing range.

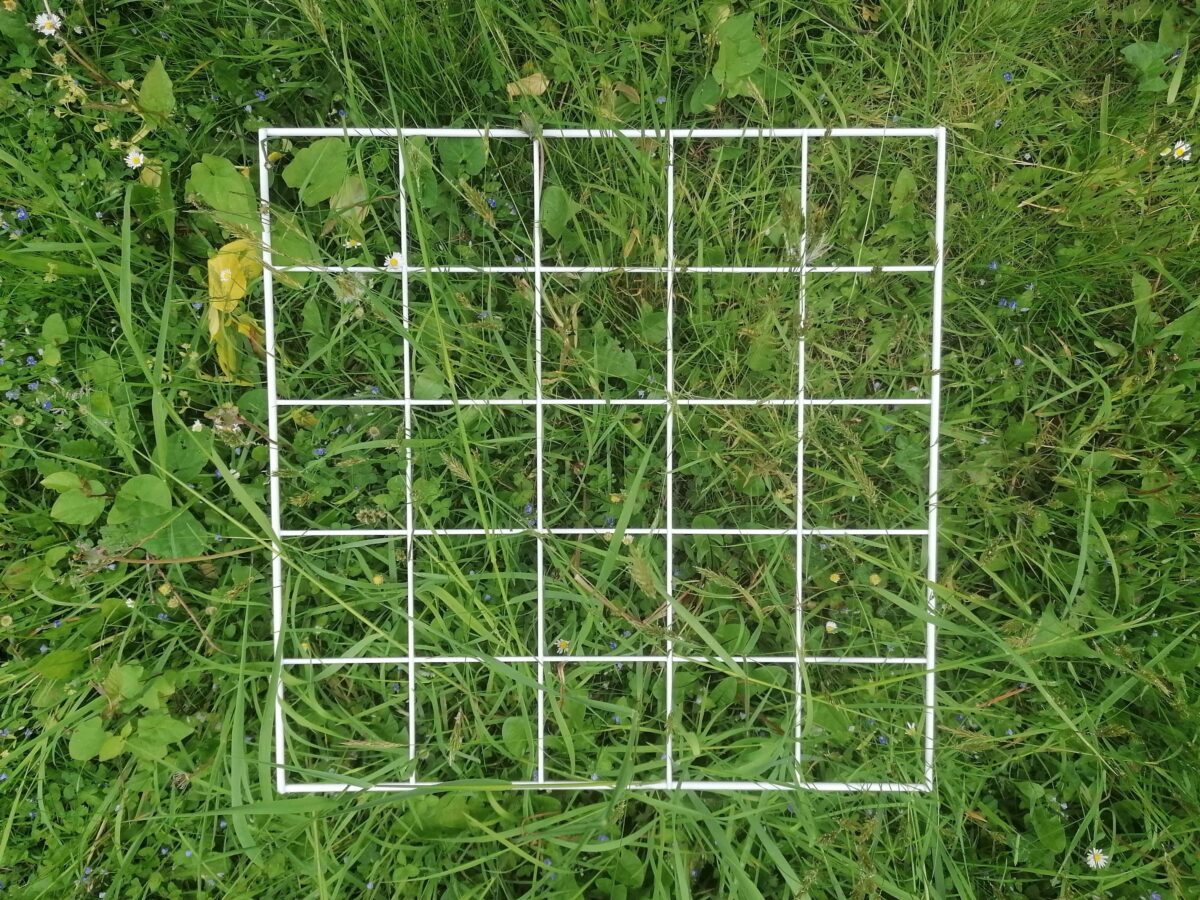

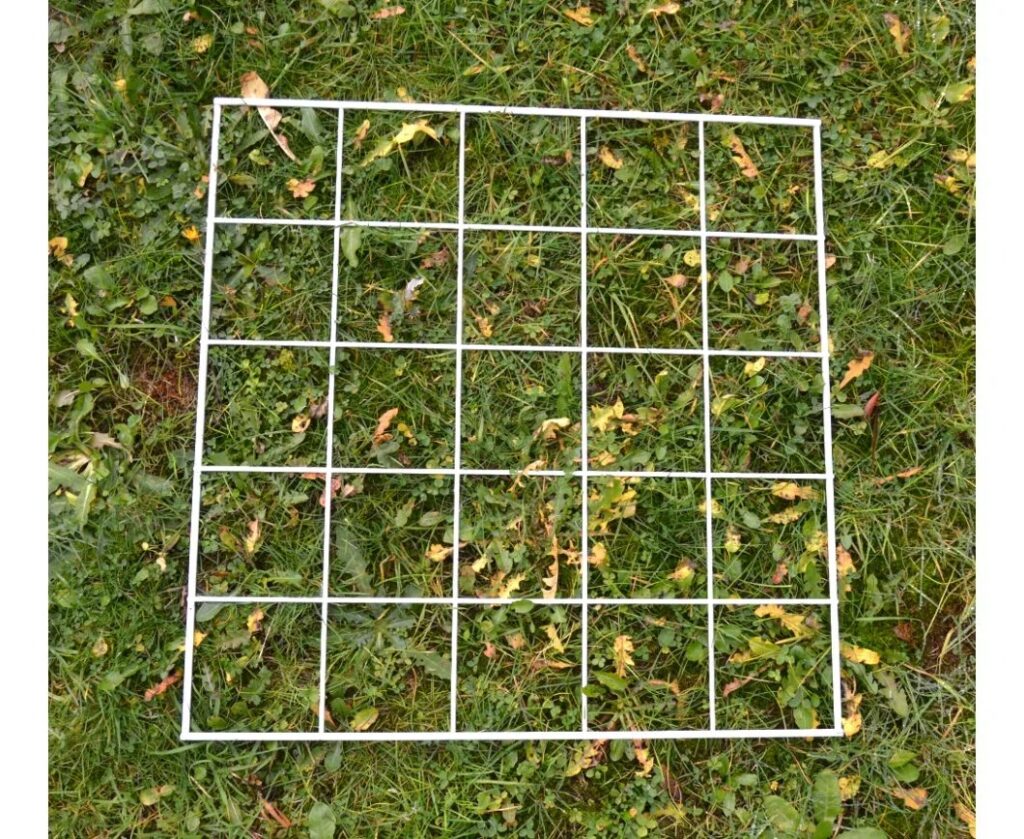

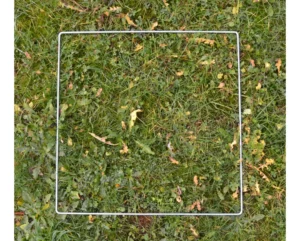

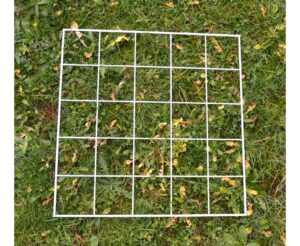

In addition to the No Mow May initiative, Plantlife have also introduced Every Flower Counts, a citizen science survey that asks participants to count, record and report back the flowers found in a single metre squared patch of lawn . This will enable them to gather important data on the impact that leaving areas to grow can have on abundance and biodiversity.

As May winds to a close, species are still beginning to emerge in our lawn ready to flower in June: Spear Thistle, Oxeye Daisy, members of the Carrot family and, with a final flourish of the month, a Bee Orchid slowly opens its blooms right by the footway, surprisingly cryptic until you meet it at ground level.

We hope that we can leave our grass uncut for a little longer so we can see who’s still there to flower, and that those of you who have participated in No Mow May may feel inspired to do the same.

Below is a list (in no particular order) of the flowering plants we discovered on our premises during No Mow May this year and a small selection of guides for wildflowers and grasses, plus some suggested reads for those who have inspired to take wild gardening further.

- White Clover – Trifolium repens

- Red Clover – Trifolium pratense

- Common Vetch – Vicia Sativa

- Germander Speedwell – Veronica chamaedrys

- Common Speedwell – Veronica persica

- Thyme-leaved Speedwell – Veronica serpyllifolia

- Common Dandelion – Taraxacum officinale

- Common Daisy – Bellis Perennis

- Meadow Buttercup – Ranunculus acris

- Creeping Buttercup – Ranunculus repens

- Cuckoo Flower – Cardamine pratensis

- Yarrow – Achillea millefolium

- Spotted Medick – Medicago Arabica

- Black Medick – Medicago lupulina

- Bluebell – Hyacinthoides non-scripta

- Cut-leaved Crane’s-bill – Geranium dissectum

- Common Mouse-ear – Cerastium fontanum

- Ribwort Plantain – Plantago lanceolata

- Bee Orchid – Ophrys apifera

- Herb Robert – Geranium robertianum

- Oxeye daisy – Leucanthemum vulgare

- Beaked Hawk’s-beard – Crepis vesicaria

- Catsear – Hypochaeris radicata

- Broad-leaved Dock – Rumex obtusifolius

- Sheep’s Sorrel – Rumex acetosella

- Southern Marsh/spotted Orchid Hybrid

- Creeping Cinquefoil – Potentilla reptans

- Primrose – Primula vulgaris

- Common Ragwort – Senecio jacobaea

- Hemlock – Conium maculatum

- Hemlock Water Dropwort – Oenanthe crocata

- Cuckoo-pint – Arum alpinum

- Scarlet Pimpernel – Anagallis arvensis

- Nipplewort – Lapsana communis

- Bristly Oxtongue – Helminthotheca echioides

- Cleavers – Galium aparine

- Ivy-Leaved Toadflax – Cymbalaria muralis

- Wood Avens – Geum urbanum

- Garlic Mustard – Alliaria petiolata

- Red Valarian – Centranthus ruber

- Hoary Willowherb – Epilobium parviflorum

- Broad-leaved Willowherb – Epilobium montanum

- Fringed Willowherb – Epilobium ciliatum

- Procumbent Pearlwort – Sagina procumbens

- Groundsel – Senecio vulgaris

- Cornsalad – Valerianella locusta

- Spear Thistle – Cirsium vulgare

- Prickly Sow-thistle – Sonchus asper

- Common Nettle – Urtica dioica

- Lesser Trefoil – Trifolium dubium

Suggested books and equipment

Wild Flower Flowcharts Species: ID the Easy Way

Wild Flower Flowcharts Species: ID the Easy Way

Spiralbound | March 2022

£6.99

A Field Guide to Grasses, Sedges and Rushes

A Field Guide to Grasses, Sedges and Rushes

Spiralbound | April 2016

£11.99

The Wild Flower Key: How to identify wild flowers, trees and shrubs in Britain and Ireland

The Wild Flower Key: How to identify wild flowers, trees and shrubs in Britain and Ireland

Paperback | March 2006

£24.99

Harrap’s Wild Flowers: A Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain & Ireland

Harrap’s Wild Flowers: A Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain & Ireland

Paperback | November 2018

£19.99

Collins Wild Flower Guide: The Most Complete Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain and Ireland

Collins Wild Flower Guide: The Most Complete Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain and Ireland

Paperback | June 2016

£24.99

Making a Wildflower Meadow: The Definitive Guide to Grassland Gardening

Making a Wildflower Meadow: The Definitive Guide to Grassland Gardening

Paperback | February 2015

£16.99

Wildlife Gardening: For Everyone and Everything

Wildlife Gardening: For Everyone and Everything

Paperback | April 2019

£14.99

Q1 Quadrat

Q1 Quadrat

£14.99

Q2 Quadrat

Q2 Quadrat

£15.50

Opticron Hand Lens 23mm 10x Magnification

Opticron Hand Lens 23mm 10x Magnification

£12.95 £14.95

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.