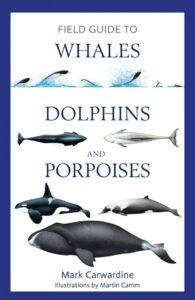

Practical and portable, this is the ultimate field guide to the world’s cetaceans. This is the most comprehensive, authoritative and up-to-date guide to whales, dolphins and porpoises. Containing more than 500 accurate illustrations – complete with detailed annotations pointing out the most significant field marks – this new field guide covers all 93 species and every subspecies in the world.

Practical and portable, this is the ultimate field guide to the world’s cetaceans. This is the most comprehensive, authoritative and up-to-date guide to whales, dolphins and porpoises. Containing more than 500 accurate illustrations – complete with detailed annotations pointing out the most significant field marks – this new field guide covers all 93 species and every subspecies in the world.

The informative text, produced in collaboration with many of the world’s most respected whale biologists, is accompanied by distribution maps, size demonstrations, dive sequences and additional information such as comparisons of silhouettes and illustrations of barnacles, lice and callosities.

Cetacean expert Mark Carwardine kindly took the time to discuss this new field guide with us, discussing how the outlook for cetaceans has changed since he first began to study them, why he chose to use illustrations over photographs and what he is working on now.

What inspired you to write this new field guide and how does it differ from your previous handbook?

The Handbook of Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises was the culmination of a life’s work, really, and took six years to research and write. It was designed as a comprehensive reference book to be used at home or in the office – and, consequently, weighs almost as much as a small porpoise. The pocket-sized Field Guide to Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises is an abbreviated (and fully updated) version, focusing more on identification, and it has been designed specifically to take into the field. Since our knowledge of cetaceans has improved so much, with new behaviour and many new species described in recent years, previous field guides (my own included) are drastically out of date. I think a new guide was desperately needed.

Your book includes a number of threatened species, including the functionally extinct Yangtze river dolphin and the vaquita, many of which we may lose entirely over the next decade. How has the outlook for whales, dolphins and porpoises changed since you first started to study cetaceans?

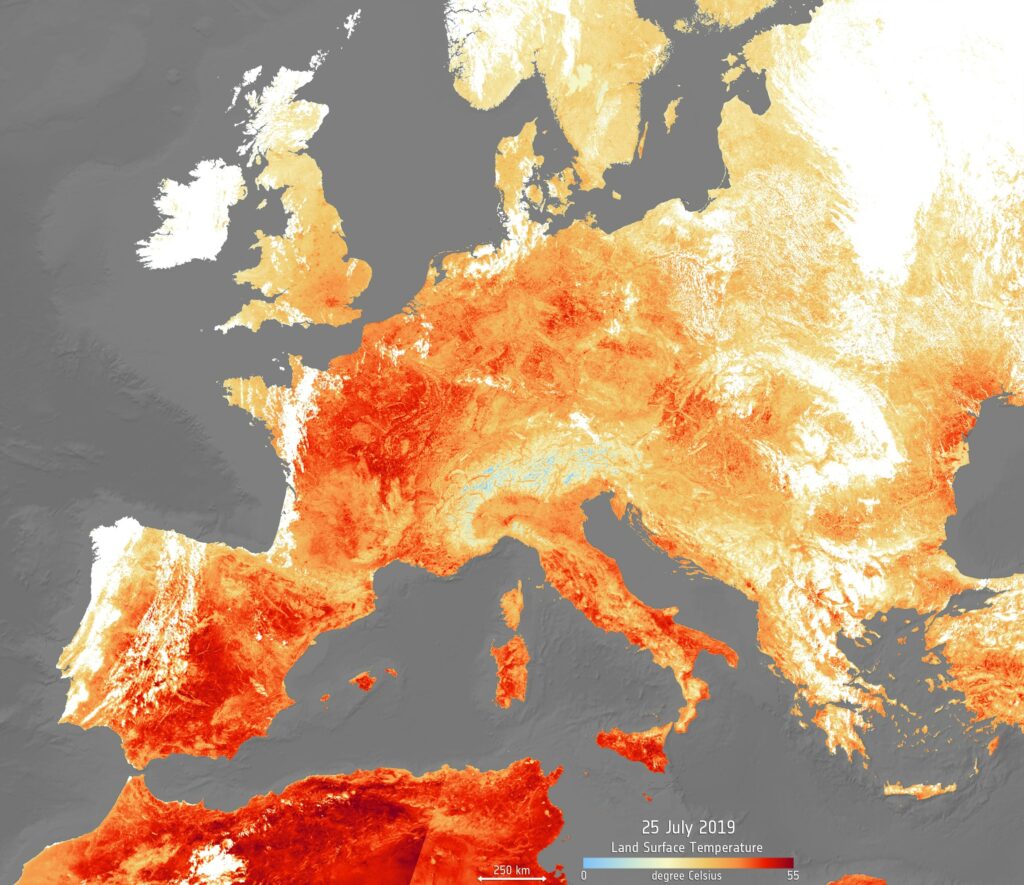

There’s no doubt that for many cetacean species, if not most, the outlook is worse than it was when I started working in this field. Some – the humpback whale is a good example – are doing surprisingly well, against all odds. But many others are not. The vaquita, we believe, is down to the last 10 individuals and is almost certainly the next (after the Yangtze river dolphin) doomed to extinction. Sadly, though, it’s not alone. The North Atlantic right whale comes to mind – there are fewer than 350 survivors and, with numbers continuing to decline, we fear for its future. Countless others are on the verge of extinction or have all but disappeared from many of their former haunts. Sometimes, I am surprised that any survive at all, given the shocking number of threats they face, such as commercial whaling and other forms of hunting, myriad conflicts with fisheries, pollution, habitat degradation and disturbance, underwater noise, entanglement in or ingestion of marine debris, ship strikes and climate change.

This field guide is full of beautiful and detailed illustrations. Why did you choose to include these rather than photographs?

I prefer the use of illustrations in field guides, because I think they demonstrate the key identification features more effectively. Also, there is a huge amount of variation within each species of cetacean – geographical variations, races and sub-species etc – and good photographs do not exist of many of the most critical ones!

Relatively little is known about the population estimates or trends of many of the species listed in this book. Why do you think this is the case, and is there ongoing research taking place to fill these knowledge gaps?

It’s true to say that our knowledge of cetaceans has grown from virtually nothing to just a little bit – despite decades of wild whale research. They are incredibly difficult animals to study, because they spend most of their lives underwater, often live far out to sea and regularly travel vast distances. They are even more difficult to count. I take people to see the friendly grey whales in San Ignacio Lagoon, Mexico, every year and we have fun trying to estimate the number of whales within the relatively small lagoon. Everyone comes up with wildly different numbers. Just imagine trying to estimate the number of minke whales, for example, in the North Atlantic. In some cases, a species is so rare that we know every individual and have an accurate population size. But in many cases it’s an informed guesstimate. The key thing is to be able to compare these guesstimates from time to time and place to place to get relative population trends. And, with some exceptions, I do think we have a pretty good idea about which species are declining and which are doing relatively well.

Is there anything that you are currently working on or do you have any plans for future projects that you would like to tell us about?

Well, I’ll never stop spending as much time with whales, dolphins and porpoises as possible! And I’ll be keeping the field guide up-to-date, of course, for future editions. But I’ve also been working on a book closer to home, called RSPB How to Photograph Garden Birds, which will be out early next year (to tie in with the RSPB’s Big Garden Birdwatch). It started as an excuse during lockdown to photograph my own garden birds but, as I developed and discovered more tricks and techniques, it gradually turned into a book. One thing I’ve learned is that you don’t have to travel to far-flung corners of the world to take great pictures of wildlife. Indeed, some of the most memorable and eye-catching images I’ve ever seen – especially while judging umpteen wildlife photography competitions over the years – have been of common and familiar species taken close to home. Yet these more ‘ordinary’ subjects tend to be ignored by many photographers. They are considered too obvious or insufficiently compelling (although I’ve never understood why because, by any standard, many of our garden birds are strikingly beautiful). While there are countless awe-inspiring images of polar bears and humpback whales, when was the last time you saw a truly inspirational image of a house sparrow or a robin, for example? Exactly. Hopefully, that’s where this book will help and inspire.

Field Guide to Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises

Field Guide to Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises

By: Mark Carwardine

Paperback | May 2022 | £12.99 £16.99

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.