Black Ops & Beaver Bombing: Adventures with Britain’s Wild Mammals is a captivating and entertaining deep dive into many of the mammals of Britain. Fiona Mathews and Tim Kendall explore mines inhabited by great horseshoe bats, go on overnight stakeouts in search of pine martens and travel from Scotland to the Isles of Scilly in search of their elusive subjects. This book puts animals at the heart of the story, revelling in their peculiarities and exploring the threats to their survival and the struggles that plague their conservation in Britain. The depth of knowledge, witty commentary and obvious enthusiam creates a beautifully written book that is difficult to put down.

Black Ops & Beaver Bombing: Adventures with Britain’s Wild Mammals is a captivating and entertaining deep dive into many of the mammals of Britain. Fiona Mathews and Tim Kendall explore mines inhabited by great horseshoe bats, go on overnight stakeouts in search of pine martens and travel from Scotland to the Isles of Scilly in search of their elusive subjects. This book puts animals at the heart of the story, revelling in their peculiarities and exploring the threats to their survival and the struggles that plague their conservation in Britain. The depth of knowledge, witty commentary and obvious enthusiam creates a beautifully written book that is difficult to put down.

Each chapter focuses on a different UK mammal, from wild boars and beavers to red squirrels and grey seals. Fiona and Tim explore the history, ecology and current conservation of these species, focusing on what is threatening them and what should or is being done to protect them. They do not shy away from giving criticism and sharing their frustration when the attitudes of policy makers stand against environmental protection and restoration. In search of answers to the problems that beset our wildlife, the authors reveal the wonder of creatures that are worth fighting for.

Fiona Mathews is a professor of environmental biology at the University of Sussex and the founding chair of Mammal Conservation Europe. Tim Kendall is a professor of English Literature at the University of Exeter and edited Britain’s Mammals 2018. They have kindly agreed to an extended interview with us, where we discuss the role of public education in conservation projects, how climate change may be impacting population recruitment in bats and seals, whether there is hope for the reintroduction of top mammalian predators, and much much more.

Could you tell us how you both became interested in mammals and what inspired you to create this deep dive into the mammals of Britain?

Tim: I grew up right next door to Devonport Dockyard in Plymouth. I was obsessed with spotting mammals as a child, but the only ones I ever saw were grey squirrels. When I was 8 or 9, I wrote a poem for school about seeing a badger, describing the joy and excitement I felt. It was all made up: I didn’t see a live badger until after I left for university. Luckily, I had the good sense to marry a mammal biologist and carry out fieldwork with her, which means that I’ve now seen all but three of our native mammal species.

Fiona: I’ve been interested in mammals for as long as I can remember, but I decided it should become my career after I went on my first bat walk. Black Ops and Beaver Bombing was partly inspired by my work reviewing the population status of Britain’s mammals and drawing up the Red List with the Mammal Society.

The preface, I-Spy, makes an interesting point about the interconnectedness of species as well as the focus of conservation: “If you want to save the barn owl, start by saving the field vole”. Do you believe the focus on ‘charismatic’ species, which are often higher up in the food chain, more often aids the conservation of prey species (such as by increasing or improving habitats) or harms these species by increasing the population of their predators? Should more conservation projects take a more ‘grassroots’ focus, by helping species lower down on the food chain?

We ignore the small species at our peril, and the fact that they’re almost all in decline is deeply worrying. Of course, wolves and wild cats grab the headlines, but if we don’t pay attention to the bioabundant species, everything across the food web is affected. We talk a lot in the book about the Scilly shrew, and if we’d thought anyone would read it, we’d have included a chapter on field voles.

In Chapter 3 ‘On the Trail of the Lonesome Pine Marten’, you discuss the extensive work done to win over the local people before the ‘recovery’ project began. Do you believe the public will become more and more open to these types of projects or will public education always need to play such an extensive role?

The general public is already becoming more welcoming, but the people who control landscapes are a small subset of the population, and they often have their own priorities that they believe (rightly or wrongly) will be damaged by reintroduction and recovery projects. One of the unfortunate things about rewilding is that it’s becoming as divisive as Brexit. We should all be working together to reverse the biodiversity crisis.

Wild mammals only make up between 2–4% of the world’s mammal biomass, decreasing by more than 85% since the rise of humans. In contrast, livestock makes up more than 63% of mammal biomass. How has this drop in wild mammal biomass impacted ecosystems and do you think we’ll be able to repair this?

High intensity livestock production is undoubtedly a massive contributor to biodiversity loss, but we mustn’t perceive farmers as the enemy. We need good farmers producing good food and getting rewarded for sustainable and wildlife-friendly production. Progress towards reforming agricultural subsidies has moved at glacial speed. Our government, like most across the globe, is much too heavily influenced by the lobbying of large agribusinesses which want to preserve the status quo.

In Chapter 5 ‘Hanging Out with Greater Horseshoe Bats’, you mention that Fiona is working on a long-term plan to re-establish the British population of the greater mouse-eared bat. Could you tell us a little bit more about how this process would work?

Fiona: Historically, the greater mouse-eared bat has been found in Dorset and Sussex, but with climate change we would expect its range to shift northwards. There are large and thriving colonies in Brittany and Normandy at the moment. We have to work out whether they will arrive in England under their own steam, or whether we need to give them a helping hand. Translocating bats isn’t easy. I’ve set up a working group at Eurobats to bring together experts looking at the best way forward.

You mention that the greater horseshoe bat population has stabilised and is now increasing in Britain. Why do you think this is happening?

The species is struggling across mainland Europe but it has responded well to a series of mild winters in England and Wales. Organisations like the Vincent Wildlife Trust have done a fantastic job to protect and improve roosts. We should remember, though, that greater horseshoes once had a range that extended to the east of England, and it’s estimated that there was a population of 300,000 at the end of the nineteenth century. The current population is about 4% of that total, which is a remarkable recovery from their lowest levels, but we need to be aware of shifting baseline syndrome before we celebrate the good news too enthusiastically.

Chapter 5 also mentions a new system for monitoring bats, which monitors the flight paths using radio receivers. Do you think that, by highlighting important flight paths, this system will be able to be used to reduce the impacts of new developments?

Although legislative protection means that we now know a lot about bat roosts in buildings, there’s not much point protecting a roost if the animals lack places to forage or mate. New techniques such as static radio tracking allow us to identify important sites and protect them for the future.

As cool weather in spring can have an impact on the growth and development of young bats, has climate change impacted juvenile survival rates and population recruitment?

We know that baby bats grow less well, with short- and long-term consequences, when weather conditions are poor in the breeding season. We would expect to see negative effects from climate change, and this is something we are currently looking at in a European-wide project. The challenge is that few researchers have datasets that span at least 20 years, which is the timeframe you need for analysing these long-term trends. So we’re also conducting other research on shorter timescales to assess whether mother bats are moving around their roosts to select different temperatures.

Chapter 6 ‘Tiggywinkle Goes Rogue’, mentions how ‘tidiness’ harms biodiversity. Do you think the growth in recent campaigns such as No Mow May will help to reduce society’s obsession with garden ‘neatness’?

Yes! It also requires us to hassle our local councils until we outnumber those strange people who complain about overgrown verges. Councils will take the path of least resistance, which should be to do as little ‘tidying’ as possible.

A common threat for several of the species you cover in Black Ops & Beaver Bombing is light pollution. Is there momentum at the moment that would see light pollution effectively combated in the coming years?

No, and the problem is worsened by the fact that lighting is getting cheaper and more intense. It’s frustrating because light is one of the few pollutants that simply disappears as soon as you flick a switch.

In chapter 7, ‘Who Cares What Colour the Squirrels Are?’, you mention that certain conservation strategies, such as the culling of grey squirrels to protect red squirrels, are unlikely to receive funding due to fears of adverse publicity. How much do you think conservation strategies are affected by how palatable they are to the public? Do you think this impacts the effectiveness of some conservation projects?

The biggest issue is the insatiable appetite for novelty over longevity. Nobody wants to fund routine maintenance. You may get grant money to reintroduce water voles, but will you still be funded to cull American mink a decade later?

As storms often lead to the deaths of many seal pups, will the increased occurrence of extreme weather due to climate change have a significant effect on population recruitment for seals on our shores?

We don’t know. In our seal chapter, we call the recovery of grey seals the great mammal conservation story of the twentieth century. Their numbers increased from about 500 during the First World War to well over 100,000, which makes up around 40% of the global population for the species. Storms and tidal surges can wipe out entire colonies of pups in any given season, but thankfully so far that doesn’t seem to have dented their population growth. Shout out to the amazing volunteers who rescue and raise pups for 6 months before they’re strong enough to be released!

The government recently released England’s first Marine and Coastal Wildlife Code, do you think this guidance will significantly help to protect wildlife such as grey and harbour seals from the impacts of visitors?

Yes. It was long overdue, and it’s vital. Some people will remember seeing the footage of a runner deliberately chasing a colony of seals into the sea in Yorkshire. If that happens to a moulting seal or a pup, they can die. We’re all tempted to take selfies next to wildlife, but it’s rarely a good idea.

This book ends by asking why Britain cannot seem to accept mammalian predators in the way that European countries have. Do you think there is hope for change in attitudes that could see the re-introduction of species such as lynx, wolves and bears within the coming decades?

We end the book in the Abruzzo National Park, 90 minutes drive from Rome, where there are now about 11 active wolf packs and 50 bears. The Cairngorms is ten times bigger, and has roughly the same human population. So much for the argument that we’re a crowded island! So we could and should reintroduce these apex predators, but we have to deal with misinformation from (for example) the current President of the National Farmers’ Union, who claims that lynx would pose a threat to ramblers. No wild lynx has ever attacked a human. Cattle, on the other hand, kill 8-10 people a year in Britain.

Do you have any future plans that you could tell us about?

We’ve just started a podcast, ‘Mammals R Us’ (https://rss.com/podcasts/mammalsrus/). We have very different working habits, so our big question is: can we finish another book without getting divorced?

Black Ops & Beaver Bombing by Fiona Mathews and Tim Kendall was published by Oneworld Publications in April 2023 and is available from nhbs.com.

Black Ops & Beaver Bombing by Fiona Mathews and Tim Kendall was published by Oneworld Publications in April 2023 and is available from nhbs.com.

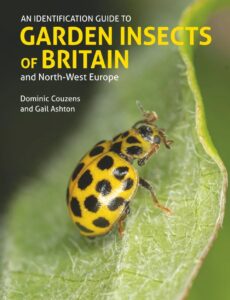

An Identification Guide to Garden Insects of Britain and North-West Europe

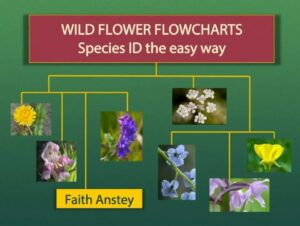

An Identification Guide to Garden Insects of Britain and North-West Europe Wild Flower Flowcharts: Species ID the Easy Way

Wild Flower Flowcharts: Species ID the Easy Way

This informative and wide-ranging book examines the nature conservation responses of the UK and twenty-five EU Member States, analysing their achievements and failures and providing notable case studies from which comparisons and lessons can be obtained. Covering topics such as biodiversity pressure, legislation and governance, biodiversity strategies, species protection, protected areas, habitat management and funding, the book provides an incredibly in-depth appraisal of our management of European ecosystems and species and how this has contributed to the current concerning state of nature in these regions.

This informative and wide-ranging book examines the nature conservation responses of the UK and twenty-five EU Member States, analysing their achievements and failures and providing notable case studies from which comparisons and lessons can be obtained. Covering topics such as biodiversity pressure, legislation and governance, biodiversity strategies, species protection, protected areas, habitat management and funding, the book provides an incredibly in-depth appraisal of our management of European ecosystems and species and how this has contributed to the current concerning state of nature in these regions.

An Identification Guide to Garden Birds of Britain and North-West Europe is a photographic guide to 75 species of bird most commonly found in or over the gardens of Britain and North-West Europe. The text combines scientific facts with affectionate descriptions of the birds’ identifying features, including sex and age differences, habits, nest types, eggs and calls. The introduction contains tips on how to identify birds, how to look after garden birds, which species can be seen throughout the year, a glossary and anatomy details. For each species, there are two or three photographs labelled with distinguishing features where appropriate, a calendar showing the time of year when the adult can be seen and star facts that give further proof of the birds’ fascinating features.

An Identification Guide to Garden Birds of Britain and North-West Europe is a photographic guide to 75 species of bird most commonly found in or over the gardens of Britain and North-West Europe. The text combines scientific facts with affectionate descriptions of the birds’ identifying features, including sex and age differences, habits, nest types, eggs and calls. The introduction contains tips on how to identify birds, how to look after garden birds, which species can be seen throughout the year, a glossary and anatomy details. For each species, there are two or three photographs labelled with distinguishing features where appropriate, a calendar showing the time of year when the adult can be seen and star facts that give further proof of the birds’ fascinating features.