Sverker Sörlin is an author, historian, and science communicator. He is currently Professor of Environmental History at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

Sverker Sörlin is an author, historian, and science communicator. He is currently Professor of Environmental History at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

He has published more than forty books including bestselling literary non-fiction, biographies, academic books and journalism. In 2004, he received the August Award for Non-fiction, Sweden’s pre-eminent literary award, and in 2024 the Inge Jonsson Prize, awarded by ‘The Nine Foundation’ for outstanding non-fiction.

We recently spoke to Sverker about his new book Snö, where he told us what inspired him to write the book, why he loves winter and the message he hoes people will take away.

You seem to have been inspired by and reflective about snow for most of your life. At which point did you decide that it was time that the ‘Angel of History’ and the ‘Snow Angel’ started talking to each other?

Yes, snow has been part of my life since I was a child in the 1950s and 1960s. My professional interest in snow and ice also began a long time ago when I was a PhD student researching the history of glaciology in the 1980s. I then worked both on and in the Arctic for a long time and led the Swedish commission for the International Polar Year 2007-2009.

It was only in the last decade, with the rise of the concept of the ‘Anthropocene’ that my outlook on snow as a ‘vulnerable element’ started to grow. In the current epoch of massive and irreversible human impact on the earthly elements, snow and ice have become, we might say, drawn into history. Snow, ice, water and also wetlands, forests, oceans, deserts, minerals and of course all sorts of life on earth are acquiring more and more ‘agency’ which is often destructive. They get this agency from the ‘human super agency’ that starts moving the entire planet faster, raising temperatures, destroying species, ecosystems and much else. In working on Snö — a History, I started to frame this as a dialogue between two angels, the ‘Angel of History’ and ‘the ‘Snow Angel’. To my knowledge, no one has ever done that so I thought it was about time. I wanted to use these concepts as metaphorical tools to draw attention to complicated matters that would otherwise require a lot of words to explain.

In your view, why is winter ‘the best season of all’, as you describe it?

Well, if you want to get into the world of snow and understand it, winter is of course the season to cherish! My appreciation of winter was also a basic value that I learned and cultivated when I was a child. I loved winter play and winter sports, like ice hockey and especially cross-country skiing. In the latter sport I had a career of sorts until I was around 20 and had to make a choice for my future -should I become a skier aiming high, or should I take university seriously I chose the latter, but it was a tough choice.

Your book weaves together religious, philosophical, and scientific perspectives. Do you ever find it challenging to intersect those attitudes? Is it ever cause for internal conflict?

In fact, this hasn’t caused a conflict for me. I also don’t confess to any religious conviction. I use the spiritual mindset to understand what goes on with me and, I assume, many other humans when we stand in front of phenomena in nature and history that are hard to fully fathom or explain. That doesn’t make me less interested in finding more knowledge about the same phenomena. In Snö I write literary non-fiction. My relationship to religion and the spiritual, but also to philosophy and the scientific, is respectful of the internal rationality of these approaches to their various versions of knowledge. I would acknowledge and, if necessary, make it clear, that these versions of ‘knowledge’, or sometimes ‘experience’ come from very different methodologies. As a scholar I subscribe with particular care to the knowledge we call scientific.

You refer to snow as ‘historical’. Could you elaborate on what you mean by this? How does snow carry or reveal history in ways that might not be immediately obvious?

It connects to what I said above on the implications of the Anthropocene. In the past, for example when I went to school and later university in the 1970s and 1980s, we learnt that ‘history’ was a record of the past that related to what humans did and thought. This required, as famously argued by British philosopher R.G. Collingwood in his book The Idea of History (written in the 1930s), a distinction between natural history (marked by aimless events) and the human history of intentional actions. What we experience in our contemporary Anthropocene world is that agency, usually reserved for humans, is increasingly distributed into what I call the ‘elemental’ categories of the world. I listed some of those above and snow is a good example.

When snow and ice (which is old, packed snow) melt in a systematic long-term fashion, it is a result of human agency through global warming. But the implications are considerable in a sequence of steps. For example, irrigation from seasonal melt becomes reduced and irregular. This affects millions of people and households south and east of the Himalayas, near the Andes in South Africa and in other regions. For the same basic reasons, the geography of winter tourism is changing, and ski resorts are closing. Snow drought appears in vast regions. Hydro-electrical production in rivers is disturbed. Extreme weather- including massive unseasonable melting means growing risk of floods. There are other cultural, social and psychological effects wrought by lack of snow and a lack of possible seasonal variations and pastimes and activities. Simply put: this is change and it is part of history since it is born out of human agency, which are to varying degrees intentional. This means it also becomes part of our responsibility, for ourselves, our nations, cities and citizens, and for this thing we used to call nature but which we now often call ‘the environment’ or ‘the planet’- or as we did long ago and now return to calling: the elements. As we speed them up and tweak and dominate them, we make them an intertwined part of our (human) history.

I think it is profound. It is an example of what we now refer to as ‘Anthropocene history’, which is an expansion, or augmentation, of the history we always had. It is, at the same time, a specialisation building on previous sub-specialties such as environmental history, history of science, history of knowledge, history of technology, climate history and a range of knowledge usually connected with geography.

Some argue that climate change is a natural, cyclical process, and therefore not something we should be overly concerned about—even if human activity is accelerating it. How would you respond to this view?

I smile and hope it will finally go away, the sooner the better. It is a long time ago that science left this position. We have known that most, almost all of our contemporary climate change is anthropogenic and stems predominantly from the human burning of fossil fuels. This has been scientific orthodoxy since around 1980 and the scientific ideas behind it date back to the 19th century. I think the only choice is to go by the established science. Anything else is unwise and will make the already severe consequences of climate change only worse and hinder the work to mitigate the change.

There’s growing discussion about how global warming, in the short term, could paradoxically lead to a long-term ice age due to the weakening or collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). What are your most recent thoughts on this anticipated event?

Not many, really. It is correct that there is growing research into this issue but is quite speculative. The likelihood of it happening is under discussion. I have no other thoughts on this issue than what you can read in any newspaper, unfortunately, including that the risks do not seem big enough, by far, to make immediate action advisable. I am sure the issue will be followed though, so that, if necessary appropriate, preparations could be considered.

In your book you mention the decline of traditional water management systems, such as the acequias in the Sierra Nevada. How do you envision the future of water management?

Oh, that is a big issue. The answer largely depends on how successful we can be in pushing back against climate change. If we can push back, we will be able to hold on better to traditional management methods, like the acequias in southern Spain. These methods are an example of how local traditions have managed to make the most of high elevation snow reservoirs and preserve them until summer and use it economically and sustainably. If we fail to push back against climate change, I fear we will need to use more and more large and heavy-handed infrastructure that is both costly and risky. Big dams are for example vulnerable targets in war. And they are often too costly in developing countries, plus water is so scarce in large regions that dams are not a solution.

Over the decades, you’ve built an extensive body of work. How did the experience of writing Snö differ from your previous books—both in terms of process and personal resonance?

Since it is a more literary work than most of my previous work, it has been a quite different experience. I based much of my work on research I did myself over many years. The challenge was to supplement this body of knowledge with new knowledge and engaging stories that in a sense filled out the gaps, both chronologically and globally. Although quite a bit of this book is centred on the north- especially the European Arctic and the Scandinavian countries- it is quite literally a global history with examples from the Mediterranean world, the European Alps (in particular Switzerland), Russia, the Americas, Antarctica, New Zealand, Australia, Asia, even Africa. It stretches across thousands of years although certainly the two last centuries take up most of the space, and our present time especially since elemental change is now so rapid and the social and political consequences so big.

There is also more history of art and literature built into the narrative that I didn’t work on so much before. Plus, a wealth of new stories that I tell which I didn’t even plan to include; I came across them in my research. One example is a long chapter called ‘Nivea’. It is about the controversial politics of the skin creme (Nivea means snow white before and during Third Reich Germany and the Nazi passion for snow. There are a number of in depth, often fascinating, stories which work as an assemblage in a literary work but may not seem relevant in a scientific journal article. The form offers a more holistic view of the topic that reaches out to a wider readership, I think.

Has the journey of writing Snö led you to any new perspectives or awareness? If so, would you care to share some thoughts?

Well, some such perspectives are presented above. All in all, I have been acutely more aware in writing this book how important snow is. Even more than I was before. It is fundamental to the water balance of the planet and to water supplies in vast regions, particularly as it functions as a holder, or a parking place for ‘slow water’. When water doesn’t slow down properly during winter and spring much of it goes away useless and can create disaster downstream. No new glaciers are being formed. The old are melting. Snow cover gets thinner and stays fewer days for every decade. We will have a planet of rapid water streams but less water security, in some areas drastically so. That has been a revelation to me.

What is the core message or insight you hope readers will take away from Snö?

First of all, I really hope that the reader appreciates this as a reading experience. Experience is unique for every reader, based on the reader’s own background, perception and imaginative powers. This is something I cherish and respect. Still, if the reader will see and take to heart some of the core ideas in the book that I have presented briefly in these answers, it is a bonus. Snow may seem a marginal thing to people in most parts of the world. But it is bigger, and more central than you might think.

Do you see enough reasons to remain hopeful for the future of the planet?

Yes, of course! Most things these days, including climate change, don’t go the right way but I am always confident. It is a better idea to retain hope and work for the better. It at least makes you feel better to work toward the good than to become cynical and opt out. Reading good, rewarding and fascinating books is to me a good part of such work.

Sverker Sörlin is an author, historian, and science communicator. He is currently Professor of Environmental History at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

Sverker Sörlin is an author, historian, and science communicator. He is currently Professor of Environmental History at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

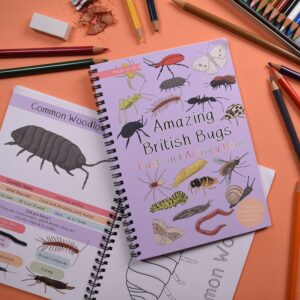

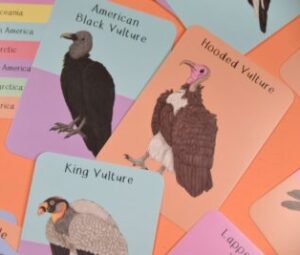

NHBS is excited to be working with Button and Squirt – a company with a strong focus and commitment to environmental education for children. Specialising in creating nature-themed educational games, Button and Squirt has a wide range of unique and engaging fact cards, activity books and other products.

NHBS is excited to be working with Button and Squirt – a company with a strong focus and commitment to environmental education for children. Specialising in creating nature-themed educational games, Button and Squirt has a wide range of unique and engaging fact cards, activity books and other products.

As a self-taught nature illustrator, Ferne Glannan-MacRae brings the intricacies of British species to life using Procreate on iPad. Her designs are inspired by a love for the environment and, in particular, British wildlife.

As a self-taught nature illustrator, Ferne Glannan-MacRae brings the intricacies of British species to life using Procreate on iPad. Her designs are inspired by a love for the environment and, in particular, British wildlife.