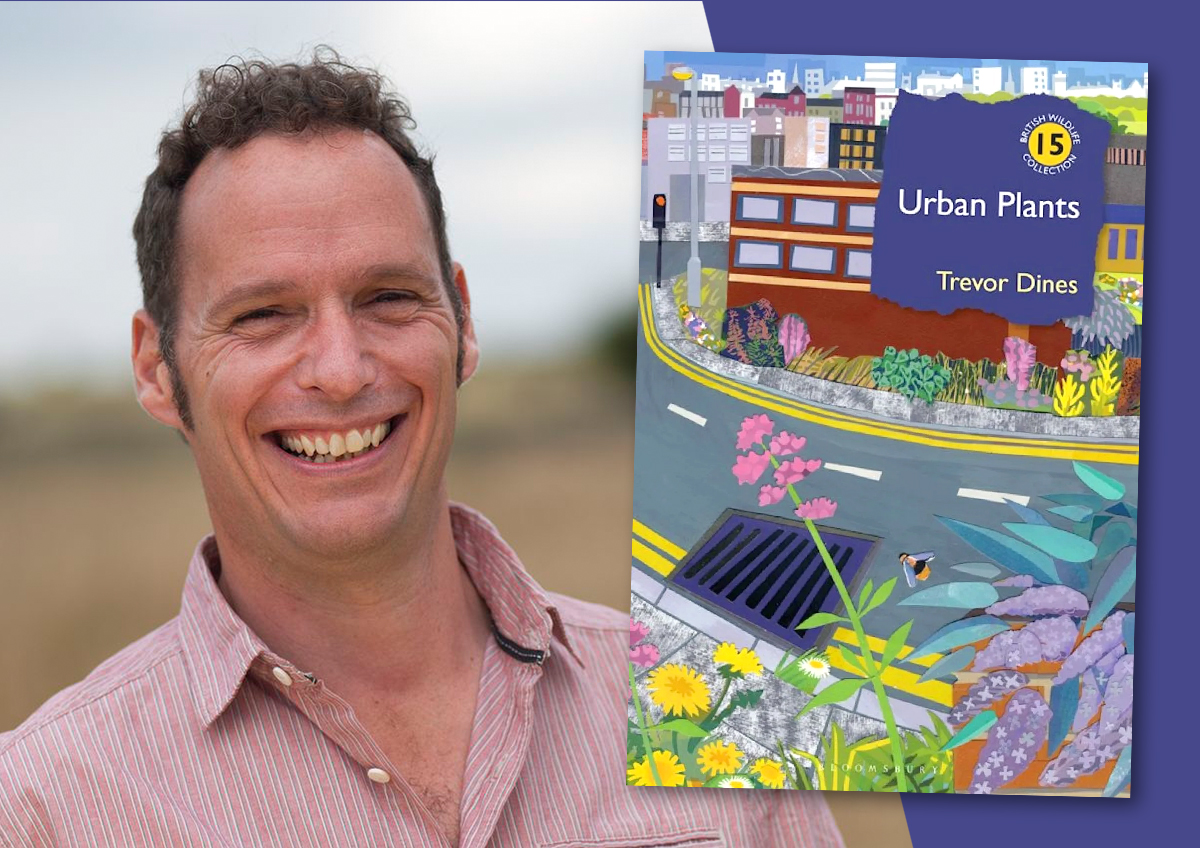

The 15th volume in the insightful British Wildlife Collection is this timely and illuminating journey into the wild lives of Urban Plants. In this book, Trevor Dines explores the floral species that pioneer our pavements and walls, break ground in our towns and cities and strive to connect corridors for pollinating invertebrates through our built-up landscapes. Trevor also looks to the future and the potential impacts of invasive species, herbicides and climate change, as well as the concept of urban rewilding.

Trevor Dines, a farmer’s son from Hampshire, co-authored the New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora, mapping every native and naturalised plant in these islands. A campaigner for better management of road verges and lawns and the creation of wildflower meadows, he appears regularly on the Radio 4 Today programme, BBC Breakfast and Countryfile. Trevor also presented Channel 4’s Wild Things and wrote the accompanying book The Wild Things: Guide to the Changing Plant Life of the British Isles.

We recently had the pleasure of asking Trevor more about why and how he came to write Urban Plants

Firstly, can you tell us a little about yourself and how you came to write the 15th volume in the renowned British Wildlife Collection?

I was incredibly lucky to grow up on two farms -one in Wiltshire and another in Hampshire -where I developed a deep passion for wild plants. I’d spend hours searching dad’s fields for rare arable flowers like Venus’s-looking-glass and Rough Poppy, as well as orchids on the chalk downland. After leaving Bangor University with a PhD in plant architecture, I worked for the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, co-authoring the New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora (2002). This is when I really got to know our flora, travelling the length and breadth of the country meeting plants and the network of incredibly talented plant recorders that are so happy to share their knowledge. For 20 years I then worked for Plantlife – the plant conservation charity – in particular championing the creation of wildflower meadows, the better management of road verges, and changing attitudes towards lawns through the invention of No Mow May.

During this time, I also presented a Channel 4 TV series (Wild Things) that showed how and why plants are changing their distributions around Britain and Ireland. This led to more work in the communications side of things at Plantlife, something I’ve always had a passion for because it’s such an important element of conservation. This was an exciting time, with appearances on BBC Countryfile, BBC Breakfast and Gardeners’ World, as well as many local radio and newspaper interviews and writing articles for magazines. Katy Roper, Commissioning Editor at Bloomsbury Wildlife, became aware of my work through an item I’d written about the spread of Oxford Ragwort and invited me to consider writing a book on urban plants for the series. I was, of course, thrilled at the prospect, and threw myself into the project in 2022 when I became a freelance botanist.

My favourite excerpt from the book was hearing about the newly established population of Lesser Tongue-orchids thriving on the roof of a large city bank. Do you have a favourite, but possibly less well-known, urban botanical enclave you can share with us?

I particularly enjoy finding mundane or even rather grotty places with completely unexpected plants. Between a footbridge and the railway into my local town, Conwy, for example, there’s a thin sliver of fallow waste ground that’s home to a very bizarre mix of plants. Alongside the usual suspects like Buddleja and Oxford Ragwort, bright pink Pyramidal Orchid and Zigzag Clover push up between clumps of Pampas Grass, an increasingly invasive garden escape from South America. And, for the last few years, Iris reticulata × histrioides ‘George’ has also flowered here, the only place in Britain where it’s known to be established outside gardens. Tantalisingly, all these plants are unreachable behind a metal fence, adding another level of challenge for the urban botanist.

There has been a sad decline in the number of higher education courses offering botany as an option. However, with the news of the natural history GCSE coming this year, how would you integrate uUrban botany into the course as a way to encourage future botanists?

Urban botany is unique in being accessible to everyone, everywhere. You don’t need to travel to a nature reserve, a woodland, a meadow or other special place to engage with it – it’s quite literally right there on your doorstep. This makes it an ideal subject for the new GCSE, and there are lots of opportunities. Students could look at the phenology of flowering through the year, counting the number of flowers in a given area from the first Dandelions and Groundsel of the year to Herb-Robert and Red Dead-nettle at Easter, and finally Red Valerian and Purple Toadflax before the end of term. Or they could study local walls, seeing how the vegetation varies according to building materials and the direction the wall faces. Or they could look at the impact of footfall on pavements, with fewer plants in areas having most pedestrian traffic. The important thing is that urban plants are fascinating because every species has a story to tell; I love the reaction from kids when you tell them that germinating seeds of Shepherd’s-purse actually kill nematodes to help them survive. It helps bring their environment alive (unless you’re a nematode!).

Rewilding is a hot topic in conservation and biodiversity, and No Mow May is a growing campaign many partake in. Can we ‘rewild’ our immediate environment with this changing mindset to benefit urban plants and biodiversity?

I’m glad you’ve put ‘rewild’ in quotes, as it’s become such a diluted phrase – it now seems to cover any conservation action, from planting wildflowers in a window box to reintroducing beavers. Rewilding in its original form (the reintroduction of charismatic mammals to kick-start natural processes) is very difficult to do in urban areas because habitats are so fragmented and anthropogenic pressures are so high. As engaging as they are, I’m afraid beavers can’t do much to improve the diversity of life in the built environment.

But for many people, rewilding simply means reining back on the intensity of management (or even abandoning management at all) and just letting things grow, seed and recover. And in this case, yes, it’s what the urban environment desperately needs. As the creator of the No Mow May campaign, it’s fantastic to see how this approach has captured people’s imaginations and encouraged us to put the mower away, hopefully not just for May but the whole of summer. The results can be spectacular, with orchids appearing on lawns and mini-meadows with carpets of White Clover, Selfheal, Bird’s-foot-trefoil and buttercups.

Urban biodiversity is all about the tension between our desire for control – an environment kept ‘neat and tidy’ through the use of herbicides, mowing and strimming – and our desire for something wilder. We are, I think, still exploring this relationship, trying to become more comfortable with ‘messier’ streets. Many towns and cities are relaxing their use of herbicides and allowing more vegetation to grow, but then often face a backlash from the neat-and-tidy brigade. Hopefully, as is the case in much of Europe, we’ll become more relaxed in the future and begin to embrace more flowers on our streets in the future.

You discuss how the successional stages of our urban landscape provide a unique opportunity for plants from around the world, which is a win for cosmopolitan biodiversity. What can we learn as individuals from the resilience of this vast array of plant life?

I think botanists inherently appreciate that diversity is not just a good thing, but the very foundation of resilience. Each species has its own suite of unique characteristics that help it survive – be it tolerance of drought or pollution, the ability to set seed within just a few weeks, or a particularly successful method of dispersal – and building communities of plants with these different traits helps them survive the intense stresses of the urban environment. We humans are just the same; we are all different, we all have different skills and talents, and we all bring something unique to the party. And if we come together and draw strength from our diversity, we’re much more likely to cope with the everyday stresses of urban life.

Finally, what’s taking up your time at the moment? Are there any other projects you’re working on that we can hear about?

I’m currently working for the Species Recovery Trust, a small but brilliant charity that’s dedicated to the long-term survival and recovery of a suite of highly threatened species. Alongside traditional conservation subjects like Field Gentian and Forked Spleenwort, I’ve just started working on Welsh Groundsel (Senecio cambrensis) – a hybrid between Oxford Ragwort and Common Groundsel. This unique endemic species is only found in north Wales where it grows along pavement edges, roadside hedgerows and on waste ground, usually in urban settings. Unfortunately, it’s fallen victim to the neat-and-tidy brigade, having been lost from dozens of sites due to herbicides and strimming. It’s now only known from five places and is on the brink of extinction, so we have a lot of work to do to bring it back. But I relish this sort of challenge and hopefully we can recover some lost populations in the next few years.

Urban Plants by Trevor Dines is volume 15 of the British Wildlife Collection published by Bloomsbury in Hardback and is available from nhbs here.

Urban Plants by Trevor Dines is volume 15 of the British Wildlife Collection published by Bloomsbury in Hardback and is available from nhbs here.