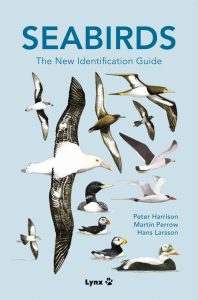

Lynx Edicions is a Barcelona-based publishing house, originally founded in 1989 to create the Handbook of the Birds of the World series. They are known for their fantastic ornithology titles, alongside a varied collection of general natural history. They have published over 150 titles, including field guides and bird checklists, and continually produce exciting works, such as their most recent publication Seabirds: The New Identification Guide, a full, 600-page treatment of all known seabird species.

Lynx Edicions is a Barcelona-based publishing house, originally founded in 1989 to create the Handbook of the Birds of the World series. They are known for their fantastic ornithology titles, alongside a varied collection of general natural history. They have published over 150 titles, including field guides and bird checklists, and continually produce exciting works, such as their most recent publication Seabirds: The New Identification Guide, a full, 600-page treatment of all known seabird species.

Lynx Edicions are our Publisher of the Month for August and have taken the time to answer some questions about their background, motivations, and current major project.

Could you please tell us a little bit about Lynx Edicions and your mission as a publishing house?

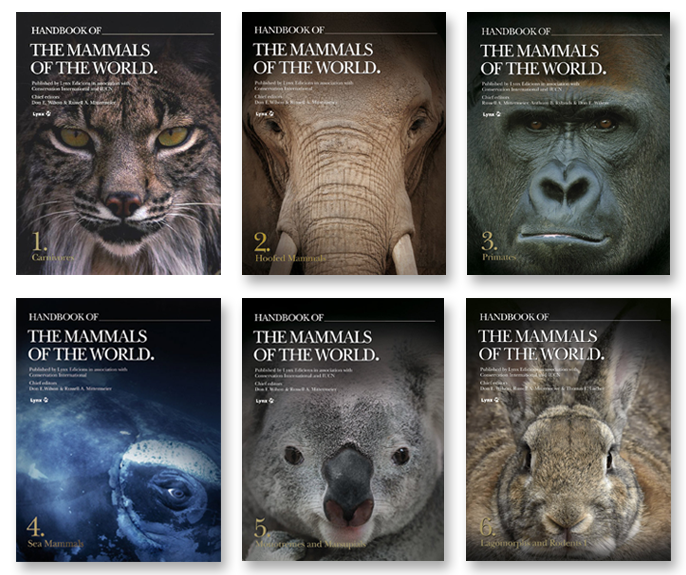

Lynx Edicions is a publishing house committed to providing high-quality ornithology and natural history books. It was founded to create the 17-volume Handbook of the Birds of the World series, the first work ever to illustrate and describe in-depth each member of an entire Class of the Animal Kingdom: Class Aves. We then applied the same detailed treatment to Class Mammalia with the Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Our work has not stopped there, but rather it has grown from this strong foundation. Furthermore, we are proud to collaborate with many different organizations and professionals to publish a wide range of titles devoted to promoting understanding and appreciation of ornithology and nature, as well as its conservation.

What inspired you to create your flagship publication, the Handbook of the Birds of the World?

In 1980, Lynx Co-founder Josep del Hoyo took a 13-month trip to Africa to explore the wildlife with a special focus on birds. In preparation for the trip, he purchased several bird field guides to help identify the species that he would be seeing. On his trip, he soon discovered that the books were not as helpful as he had imagined – they lacked details and, in some cases, they even lacked species! The experience with the books was frustrating, but Josep just thought that he had purchased the wrong books and that certainly a definitive work covering all the birds existed. However, when he returned from the trip and searched for a comprehensive treatise dedicated to birds, he surprisingly found there was none. This inspired him to create one himself and he was fortunate to find two partners, Jordi Sargatal and Ramón Mascort, to join him in this monumental effort. Together they founded Lynx Edicions in 1989 and set to work on the Handbook of the Birds of the World project.

What is the process of creating handbooks of this scale? What are the challenges involved?

Creating handbooks of this large scale involve a huge amount of collaborative effort and intricate coordination of data, materials, processes and professionals. For example, the Handbook of the Birds of the World includes detailed texts and high-quality illustrations from 277 specialists and 33 illustrators from 40 countries. The impactful photographs are the contributions of more than 850 photographers from all over the world. Of course, behind the scenes is also the hard work of a carefully orchestrated team including editors, coordinators, and production staff, as well as those dedicated to the logistics of selling and distributing the books across the world.

In addition to the challenges inherent in producing such a vast work, there are also challenges related to the important focus of the handbooks – the birds and mammals themselves – with information on species sometimes hard to find. Luckily the international ornithological and mammalogical communities have been highly supportive of the Handbook projects and have come to our aid repeatedly with data, photographs and other help to treat all the world’s birds and mammals in detail. We hope that, in a small way, the Handbooks have also encouraged some professionals to investigate, photograph and even protect species that had formerly not received as much attention.

The Handbook of the Birds of the World includes sections on species known to be extinct; why was this information important to include?

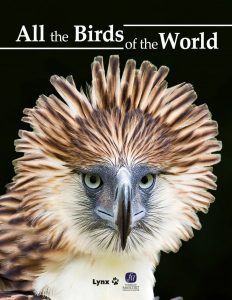

Conservation has always been an important goal of our publications, and we believe that “you cannot protect what you do not know”. So, to start, we aim to explain and illustrate the wonders of the natural world, so that people can see its value and fight to protect it. Another aspect is showing the reality of extinction and those remarkable species that we have already lost, which will hopefully lead people to act to avoid more species crossing  the line into extinction. In our Handbooks, Illustrated Checklists, Field Guides and most recently All the Birds of the World, we have included the IUCN/BirdLife International conservation status for every species to help call attention to these important data. We have been very fortunate to collaborate with BirdLife International, Conservation International, IUCN, Re:wild and other international organizations to pursue the important goals of conservation through our work.

the line into extinction. In our Handbooks, Illustrated Checklists, Field Guides and most recently All the Birds of the World, we have included the IUCN/BirdLife International conservation status for every species to help call attention to these important data. We have been very fortunate to collaborate with BirdLife International, Conservation International, IUCN, Re:wild and other international organizations to pursue the important goals of conservation through our work.

One of the publishing house’s main areas of expertise is in ornithology, with publications including field guides, illustrated checklists, and guides to bird conservation. What, in your opinion, are the greatest threats to bird biodiversity?

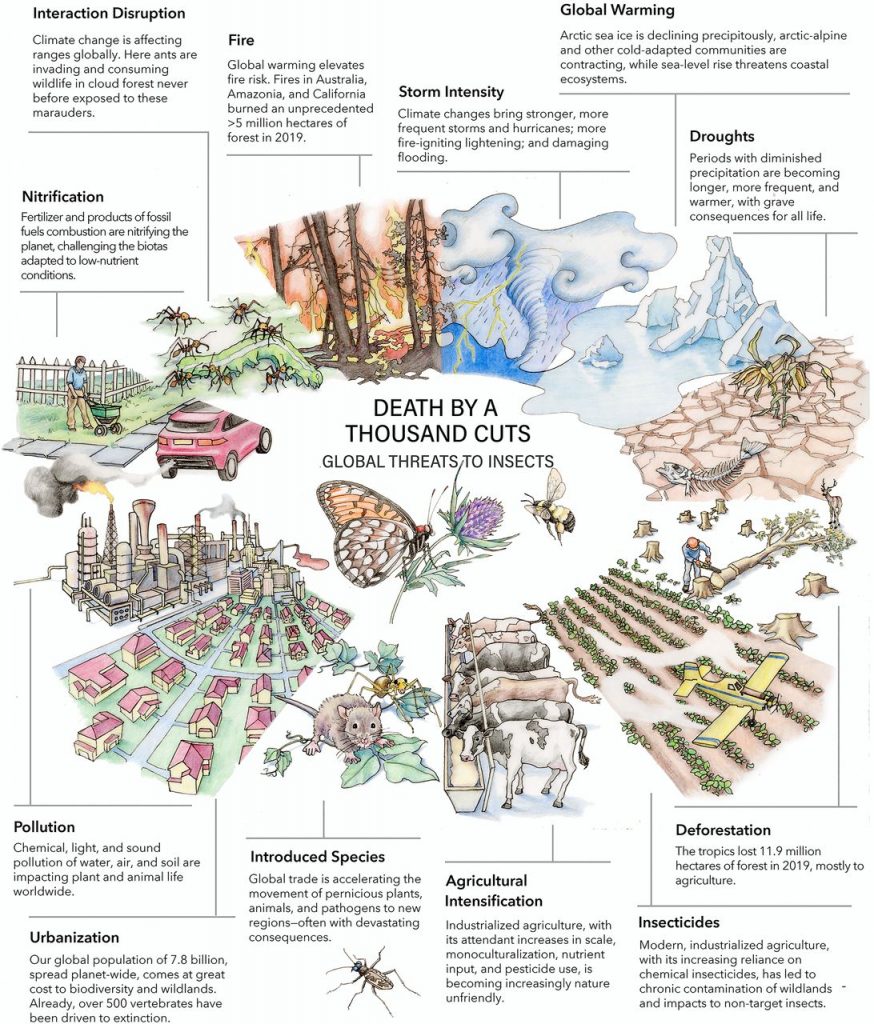

Habitat loss is probably the greatest threat to biodiversity on Earth today and it is certainly a devastating threat to bird biodiversity. In turn, habitat loss is directly related to human action as we modify and reshape the Earth for our uses. For example, some of the top threats to birds are related to habitat destruction and degradation, like agriculture, logging, invasive species, and climate change. Action by humans has been especially detrimental to forests, grasslands, wetlands, and other freshwater habitats.

We feel it is important to educate people about the importance of birds and their natural habitats, so that they can be encouraged to protect them and to find ways to coexist harmoniously. This is what has also inspired us to pursue our Field Guide collection for birds, as well as our Illustrated Checklist collection for mammals, in order to give local communities and travellers the tools to discover and protect local species and their habitats.

A current, major project is the Lynx and BirdLife International Field Guide Collection. Can you tell us a little about the motivation behind this series and why it is so important?

Carrying on from the previous point, this project came to life after years of conversations motivated by a shared idea between Lynx and BirdLife International that the existence of country field guides is a basic element for the “emergence” and education of birdwatchers, ornithologists, bird guides and naturalists in any given country, which, in turn, has important repercussions on the conservation of nature and biodiversity, both locally and globally. The principal goal of this collection is to produce modern, standardized field guides, especially for countries without any recent or country-level guide. The main collection is produced in English, including local-language names for the species when an official list exists. But we also have a secondary goal of publishing several of the titles in their local languages to enhance the local effects of the work. We are delighted by the success of the collection so far, with a growing number of titles authored by top experts, and we look forward to producing more now that hopefully travel will increase again after the challenging times of the COVID-19 pandemic.

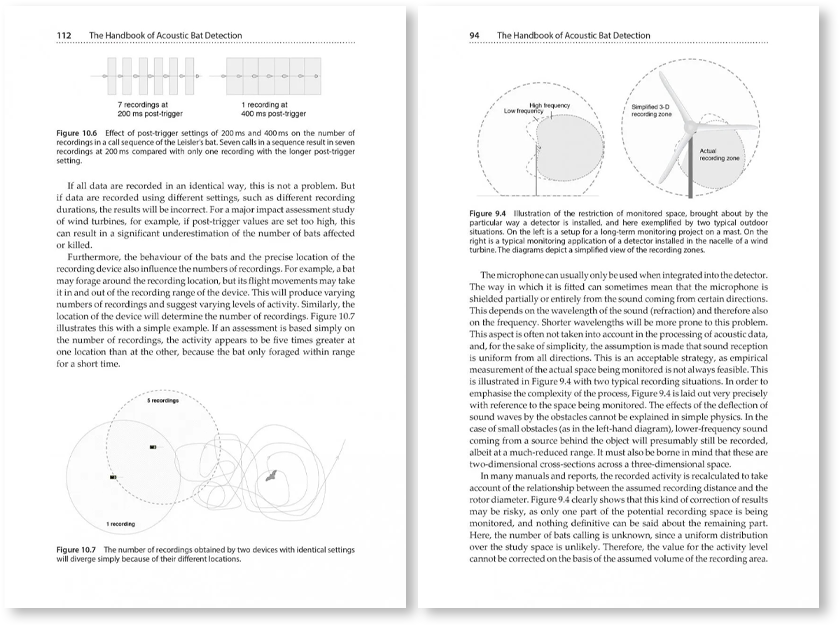

Acoustic detection is a popular and widespread method of environmental assessment, and its use is increasing, driven by the development of increasingly accessible and sophisticated detection devices.

Acoustic detection is a popular and widespread method of environmental assessment, and its use is increasing, driven by the development of increasingly accessible and sophisticated detection devices.

In his latest book,

In his latest book,  shapes, forms and colours of the birds. They were so very different to the birds I was used to seeing in the Somerset countryside around our home. After that, every now and again I’d see footage of hummingbirds on wildlife documentaries, and began to appreciate further just how remarkable they were – what Tim Dee described as ‘strange birds: not quite birds or somehow more than birds, birds 2.0, perhaps’.

shapes, forms and colours of the birds. They were so very different to the birds I was used to seeing in the Somerset countryside around our home. After that, every now and again I’d see footage of hummingbirds on wildlife documentaries, and began to appreciate further just how remarkable they were – what Tim Dee described as ‘strange birds: not quite birds or somehow more than birds, birds 2.0, perhaps’. There were plenty of other moments that I’ll hold in my heart, and they don’t all involve the iconic, rare species. One such was watching Golden-tailed Sapphires, a hummingbird that looks as if it’s been dipped in rainbows, feeding in a clearing in the immediate aftermath of a heavy rain shower. As the sun broke through the dripping vegetation and steaming air we were suddenly surrounded by myriad small rainbows through which the birds were flying. That moment was ephemeral, over almost as soon as it began, but it’s etched in my memory forever.

There were plenty of other moments that I’ll hold in my heart, and they don’t all involve the iconic, rare species. One such was watching Golden-tailed Sapphires, a hummingbird that looks as if it’s been dipped in rainbows, feeding in a clearing in the immediate aftermath of a heavy rain shower. As the sun broke through the dripping vegetation and steaming air we were suddenly surrounded by myriad small rainbows through which the birds were flying. That moment was ephemeral, over almost as soon as it began, but it’s etched in my memory forever.  I found myself asking myself that very question as my journey into their world unfolded… Hummingbirds certainly seem to touch something deep inside us. They featured in the mythology of the Aztecs; inspired the most dramatic of all of the immense geoglyphs carved into the desert floor by the Nazca; appear in renowned art and literature; and, to this day, are singled out for particular love by those whose gardens they frequent, people who would not necessarily identify themselves as birders.

I found myself asking myself that very question as my journey into their world unfolded… Hummingbirds certainly seem to touch something deep inside us. They featured in the mythology of the Aztecs; inspired the most dramatic of all of the immense geoglyphs carved into the desert floor by the Nazca; appear in renowned art and literature; and, to this day, are singled out for particular love by those whose gardens they frequent, people who would not necessarily identify themselves as birders. Inevitably there were some logistical challenges to contend with, not least having to reacquaint myself with horse-riding after a decades-long and deliberate avoidance of it! There were a couple of close encounters with large predators that were, in hindsight, more alarming than they felt at the time – as a naturalist, I was thrilled to get (very) close views of a puma… But perhaps the most challenging moment of all was landing in Bolivia at the very moment the country was taking to the streets to protest the outcome of a recent presidential election. There was an incident at a roadblock manned by armed men that was genuinely scary, with an outcome that hung in the balance for a terrifying instant, and could easily have ended badly.

Inevitably there were some logistical challenges to contend with, not least having to reacquaint myself with horse-riding after a decades-long and deliberate avoidance of it! There were a couple of close encounters with large predators that were, in hindsight, more alarming than they felt at the time – as a naturalist, I was thrilled to get (very) close views of a puma… But perhaps the most challenging moment of all was landing in Bolivia at the very moment the country was taking to the streets to protest the outcome of a recent presidential election. There was an incident at a roadblock manned by armed men that was genuinely scary, with an outcome that hung in the balance for a terrifying instant, and could easily have ended badly. I sometimes think there’s almost too much optimism expressed when talking about conservation challenges anywhere in the world – a narrative that suggests “if we only care enough, the [insert iconic species name here] can be saved”. And to a degree, that’s good – we’ve got to have hope, as the alternative is too dreadful to countenance – but given our impact to date, and in an uncertain future where the effects of climate change are still unfolding and will continue for many decades to come, to name just the biggest of the mounting pressures on the natural world, I’m not sure that I do feel terribly optimistic, least of all for those hummingbird species that have very localized populations, or depend upon very specific habitats. They’re undeniably vulnerable. But like Fox Mulder,

I sometimes think there’s almost too much optimism expressed when talking about conservation challenges anywhere in the world – a narrative that suggests “if we only care enough, the [insert iconic species name here] can be saved”. And to a degree, that’s good – we’ve got to have hope, as the alternative is too dreadful to countenance – but given our impact to date, and in an uncertain future where the effects of climate change are still unfolding and will continue for many decades to come, to name just the biggest of the mounting pressures on the natural world, I’m not sure that I do feel terribly optimistic, least of all for those hummingbird species that have very localized populations, or depend upon very specific habitats. They’re undeniably vulnerable. But like Fox Mulder,

As recently featured on

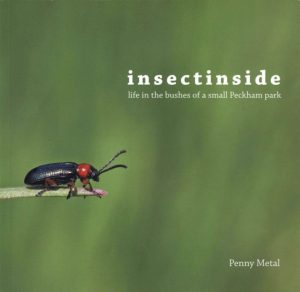

As recently featured on  photographing and surveying insects. I learned about the insects, watched them and counted the sheer number of species, and realised that no one else had actually surveyed a small urban park extensively. The book came about as I wanted to show people what was living in the bushes and to put Peckham on the entomological map!

photographing and surveying insects. I learned about the insects, watched them and counted the sheer number of species, and realised that no one else had actually surveyed a small urban park extensively. The book came about as I wanted to show people what was living in the bushes and to put Peckham on the entomological map!

and usually open 24 hours – but there is no reason why we can’t include habitats for our wildlife. A simple solution would be to leave areas un-mowed to grow wild. In the parks of my local area in London, large swathes of grasses and flowers have been left to mature and people have been really receptive to it. I think we are finally moving away from the Victorian ideal of neat and tidy!

and usually open 24 hours – but there is no reason why we can’t include habitats for our wildlife. A simple solution would be to leave areas un-mowed to grow wild. In the parks of my local area in London, large swathes of grasses and flowers have been left to mature and people have been really receptive to it. I think we are finally moving away from the Victorian ideal of neat and tidy!