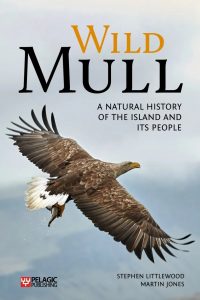

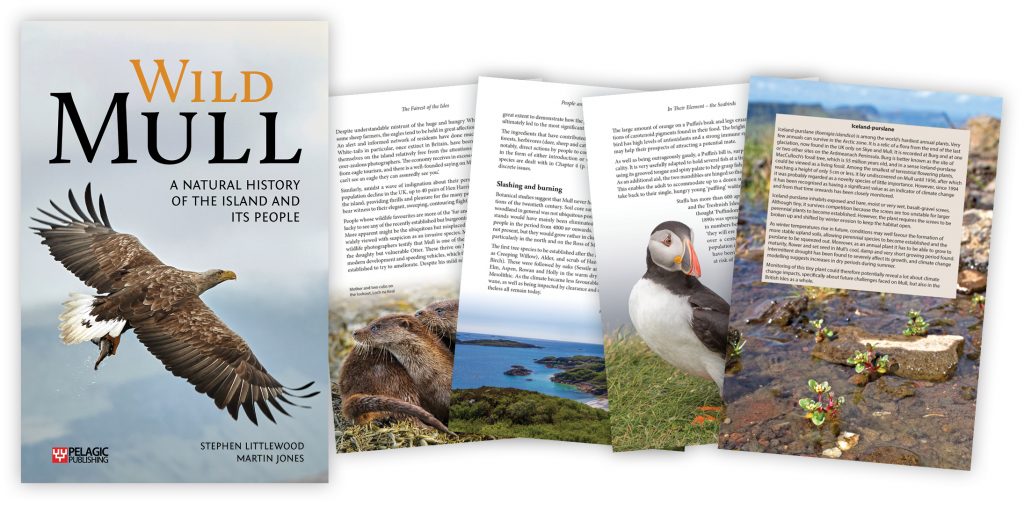

Wild Mull: A Natural History of the Island and its People guides the reader through the world of the Isle of Mull in its glory, considering every facet of the island’s natural history, diverse species and stories of past, present and future.

Wild Mull: A Natural History of the Island and its People guides the reader through the world of the Isle of Mull in its glory, considering every facet of the island’s natural history, diverse species and stories of past, present and future.

Mull is a seaborne landscape off the west coast of Scotland, displaying uncommon biodiversity and full of rare wildlife experiences, but today it faces some of its greatest challenges. With superb illustrations and illuminating text, Wild Mull is testimony to the power of wild places and the duty we have to protect and learn from them.

Stephen Littlewood kindly agreed to answer some of our questions below.

Could you tell us what inspired you to write this natural history of the Isle of Mull and its people?

We live in an era when wildlife is being pushed more and more into the margins, and many people are starved of the experience and understanding of wild places. In this context, there is a consensus that Mull is formidably equipped to display a concentration of land and marine species that is very rare today. It is also a relatively accessible destination. Consequently, the island and its surroundings have become significant attractions for a burgeoning population of wildlife tourists and, it must be said, for the tourism industry which has prospered on the back of a fascination with the so-called ‘wild’. Today, Mull’s reputation for delivering outstanding and intimate associations with many iconic British species draws people from far and wide. However, until now there has been no single resource that explains how Mull came to this position, or what it is about its aggregation of species and habitats that makes it so outstanding. I felt that it was high time to rectify that, but in doing so it was important to address some of the questions that are often overlooked during the pursuit of the profound pleasure to be gained from embracing nature in cherished land and seascapes. The book was always intended to be as much a history, an explanation and an exploration of this special place, as it was a guide to its species and habitats.

Visitors typically arrive on Mull with a wish-list of species to see. That list is invariably topped by eagles (white-tailed and golden), otters, puffins, and cetaceans. What people tend to be less appreciative of, or often not at all interested in, is the backstory both to these species and of the multitude of supporting flora and fauna. All of them are equally beautiful and extraordinary in different ways, and it is the sum of their parts that enables the headline species to thrive. I wanted to encourage the reader to explore as much of Mull’s complex biodiversity as possible, whilst also explaining how, in such an apparently injury-free landscape, it is constantly under pressure and subject to continual interventions by people, in the same way as anywhere else. To do so the book had to be factual but at the same time attractive and not overbearing. This meant that it would have to deliver a visual thrill; to make all of it, even the smallest elements, tangible and exciting. I also knew that Martin could sprinkle that magic, embroider the broad design concept, and embellish the text with the kind of high-quality photo images that would prove irresistible to the potential readership. He has done this wonderfully well.

You mention that human intervention has had a profound effect on Mull. Could you tell us a little more about the historical relationship between humans and the environment on the island?

Mull’s environment isn’t perfect, or unblemished. Most of that is down to the fact that people have been surviving on, profiting from, and ‘improving’ it for 10,000 years. If we were going to tell an honest story of the island’s natural history, it had to include the role of people, for better or worse, in shaping it. To begin with, I thought that this would be a tale largely of land use, of subsistence arable farming, grazing by domestic animals, wholesale planting and harvesting of cash-crop conifer plantations and so on. Of course, these are significant elements in the story, but only when I started to examine the historical record did I realise the extent to which species have been manipulated, consciously and unconsciously, by human interventions that have fundamentally impacted the flora and fauna over time. The picture of what we think of as a natural biodiversity, not only on Mull, isn’t necessarily as we perceive it. An extraordinary proportion of our flora and fauna has been introduced, exterminated, or tampered with. What I find interesting is that each time these actions have occurred they have been judged by the social, moral or economic expediency of the age. Today, we may feel confident that we know the right and wrong ways of addressing biodiversity issues, but one wonders if future generations will have a different perspective again.

The pine marten is flourishing on Mull, which is considered by some to be a success story, given their critical status in England and Wales. However, you highlight their potential negative impact on many of Mull’s endangered bird species. How does Mull plan to tackle this conservation conundrum?

In short, Mull doesn’t plan to tackle it at all nor, I think, is it a topic that is widely discussed. The pine marten is a very recent arrival on the island, and although it was not ‘formally’ introduced, it is generally accepted that it is here to stay. Its presence is mostly felt by the inhabitants to be desirable, so hopefully, its impact upon other species will not be to drive them beyond sustainable populations. Its role as a new predator does raise interesting questions, however. It is certainly thriving, but nobody is monitoring the impact of its reintroduction, nor the size of its population. It is a protected species in Scotland, so, therefore, cannot be deliberately trapped, whilst at the same time, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) have said that, because its introduction was never officially sanctioned, if it is accidentally caught in mink traps, for example, it should be removed from the island as an illegal immigrant and liberated elsewhere. We don’t really know if its migration is good or bad for Mull’s wildlife, and we don’t have any inclination to find out. I find this a confused response and a fascinating conundrum in the light of current approaches to the restoration of our damaged environments.

Tourism, particularly ecotourism, contributes a large proportion of the island’s economy. However, negative aspects of ecotourism, such as overuse of areas, can lead to environmental damage. What measures are being taken to keep tourism sustainable?

Ecotourism is probably now the largest contributor to the economy of Mull, but again this isn’t a question that is really generating much deliberation about the future or consideration of potential interventions. There are parking issues, particularly in the centre of Tobermory, which have been the subject of debate and are likely to result in the community and local authority trialling solutions to excess traffic in urban areas. However, in terms of ameliorating traffic growth on the roads, the impact of ‘wild’ camping, or the increasing pressures on species such as puffins and otters by wildlife photographers and so on, there is little formal debate and very little coming forward by way of attempts to make tourism more sustainable to protect the environment. It was interesting, whilst writing the book, to reflect upon the significant behavioural responses of wildlife during the Covid-19 lockdowns. There were many discernible changes, both as a response to restrictions upon tourism and the subsequent lifting of those restrictions.

Do you have any future projects planned that you can tell us about?

Mull could be likened to an accessible ‘mini laboratory’ with the potential to explore many environmental issues which are being played out on a much bigger stage. I would like to use the prism of Mull to address some of the big questions that arose in writing the book, although unpacking and making sense of the many wicked issues that come to mind is a complex and hazard-strewn path which would be a wholly different kind of journey. In the meantime, perhaps Martin and I will further develop some of the core themes of this book, which continue to fascinate and engage an ever-increasing number of interested individuals.

Wild Mull: A Natural History of the Island and its People

Wild Mull: A Natural History of the Island and its People

Stephen Littlewood (Author) and Martin Jones (Photographer) | October 2021

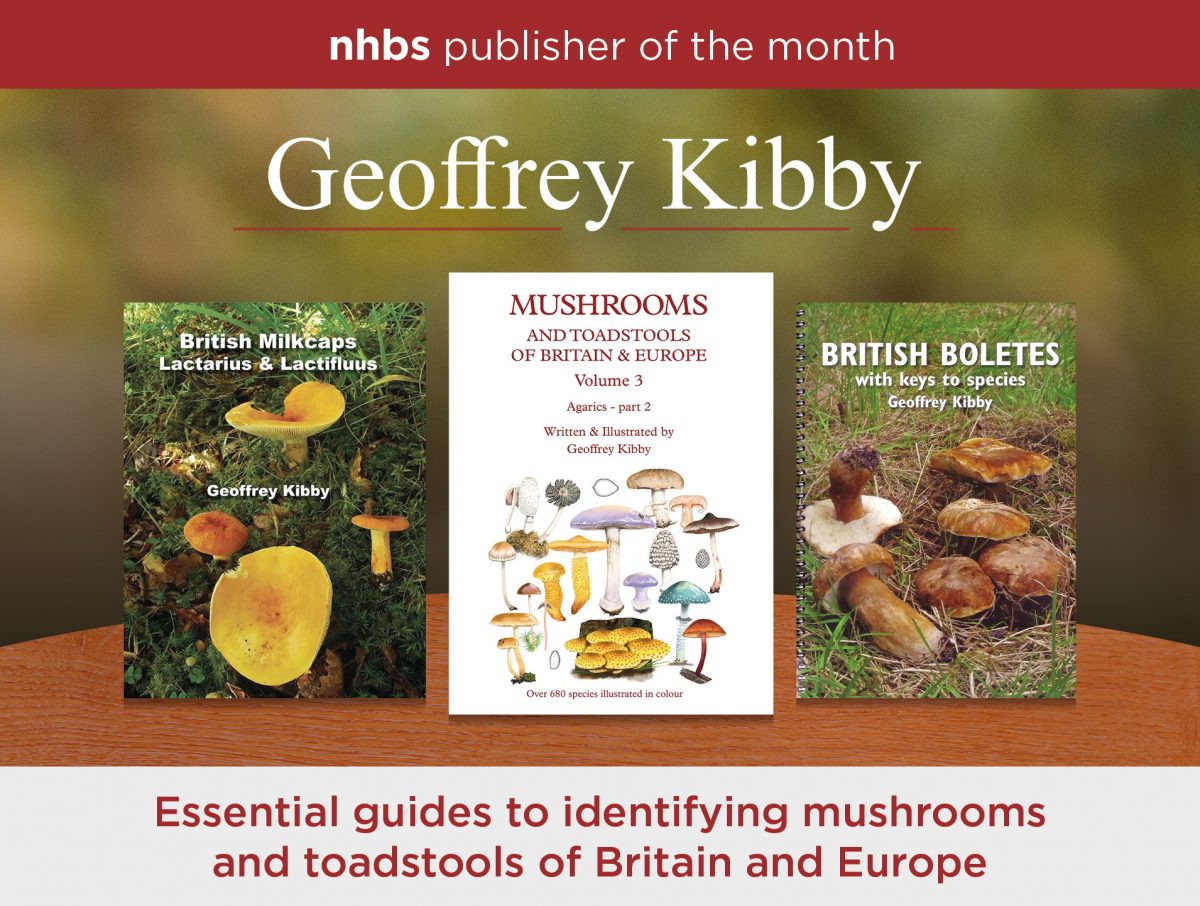

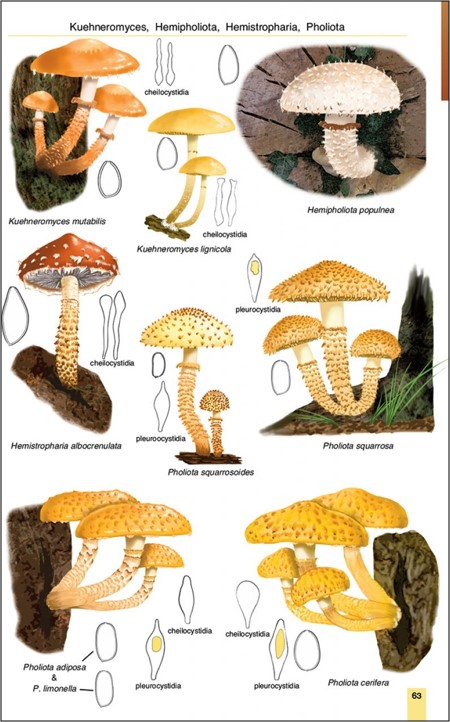

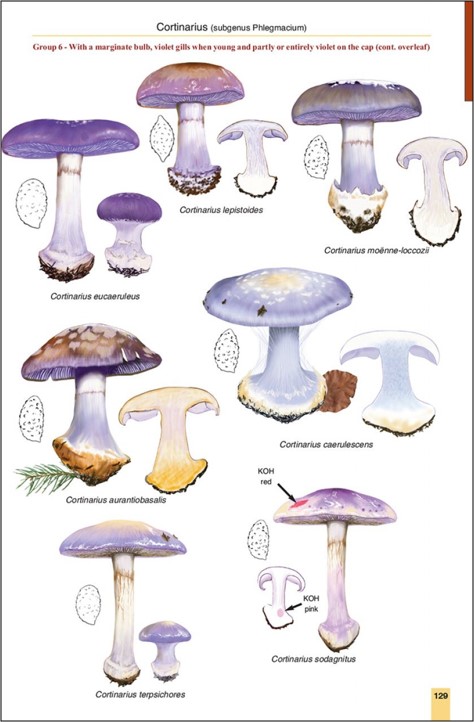

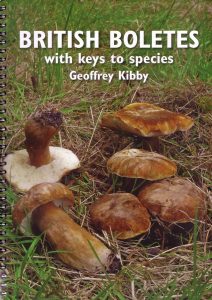

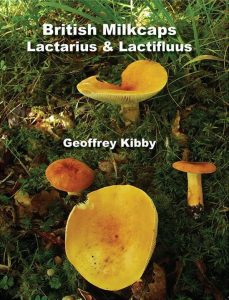

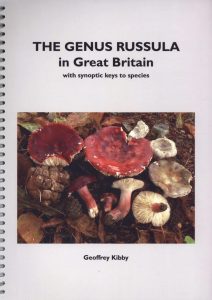

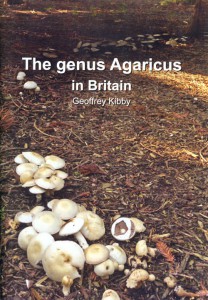

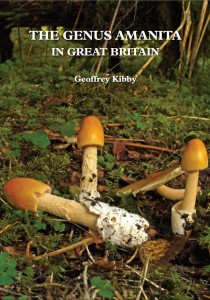

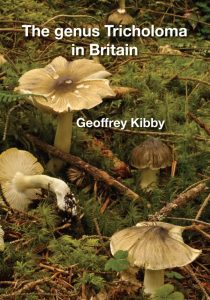

Geoffrey Kibby is one of Britain’s foremost experts on identifying mushrooms in the field, and his privately published books on how to identify British mushrooms pass on many of those skills. Kibby’s user-friendly books contain an enormous amount of information, are fully illustrated and are aimed at everyone, from the fungi enthusiast to the expert mycologist. The wealth of detail includes vital features to look for when identifying wild mushrooms and the important identification characteristics when using a microscope, often an essential tool in mycology.

Geoffrey Kibby is one of Britain’s foremost experts on identifying mushrooms in the field, and his privately published books on how to identify British mushrooms pass on many of those skills. Kibby’s user-friendly books contain an enormous amount of information, are fully illustrated and are aimed at everyone, from the fungi enthusiast to the expert mycologist. The wealth of detail includes vital features to look for when identifying wild mushrooms and the important identification characteristics when using a microscope, often an essential tool in mycology. I was 13 when I first became aware of fungi: an intensely violet toadstool, unlike anything I had ever seen (Laccaria amethystina) and from that moment, I was hooked. I bought my first little mushroom guide, then another and another and more through the years until my bookshelves started to groan under the weight of books about fungi. Now, more than 50 years later, I am writing my own books, trying to produce the sort of works that I would have wanted as an aspiring young mycologist. My books are based on my years in the field, hopefully capturing the essence of each species. I have also made a conscious point of illustrating species not readily available in other guides and trying to give the most up-to-date names in what is an ever-changing science. Mycology is an inexhaustible field of study at whatever level your interest lies. With over 4000 species of larger fungi in Britain, you will never run out of species to find or new facts to discover.

I was 13 when I first became aware of fungi: an intensely violet toadstool, unlike anything I had ever seen (Laccaria amethystina) and from that moment, I was hooked. I bought my first little mushroom guide, then another and another and more through the years until my bookshelves started to groan under the weight of books about fungi. Now, more than 50 years later, I am writing my own books, trying to produce the sort of works that I would have wanted as an aspiring young mycologist. My books are based on my years in the field, hopefully capturing the essence of each species. I have also made a conscious point of illustrating species not readily available in other guides and trying to give the most up-to-date names in what is an ever-changing science. Mycology is an inexhaustible field of study at whatever level your interest lies. With over 4000 species of larger fungi in Britain, you will never run out of species to find or new facts to discover.

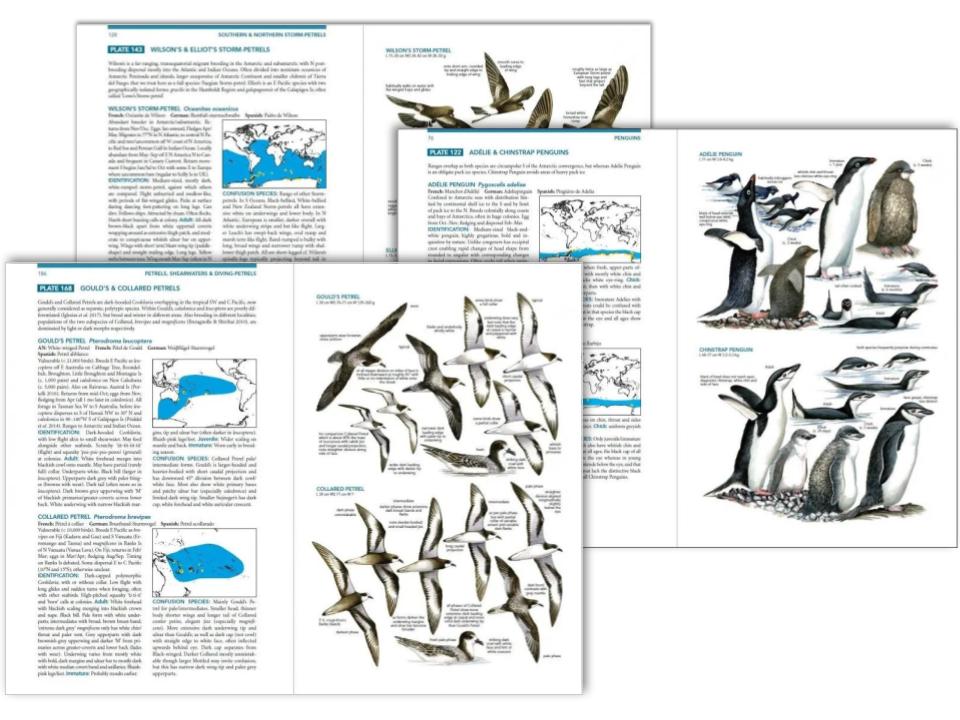

I originally trained as a mechanical engineer but ‘jumped ship’ in the 70s to take up my real love as a wildlife artist, with a focus on birds. I made this leap with much encouragement from my wife Marie and a great deal of help and inspiration from well-known bird artist Robert Gillmor, bird photographer Eric Hosking and the great East African ornithologist John Williams. I had no intention of working on book illustrations, but I got caught up in it, really liked it and I have enjoyed it ever since.

I originally trained as a mechanical engineer but ‘jumped ship’ in the 70s to take up my real love as a wildlife artist, with a focus on birds. I made this leap with much encouragement from my wife Marie and a great deal of help and inspiration from well-known bird artist Robert Gillmor, bird photographer Eric Hosking and the great East African ornithologist John Williams. I had no intention of working on book illustrations, but I got caught up in it, really liked it and I have enjoyed it ever since.

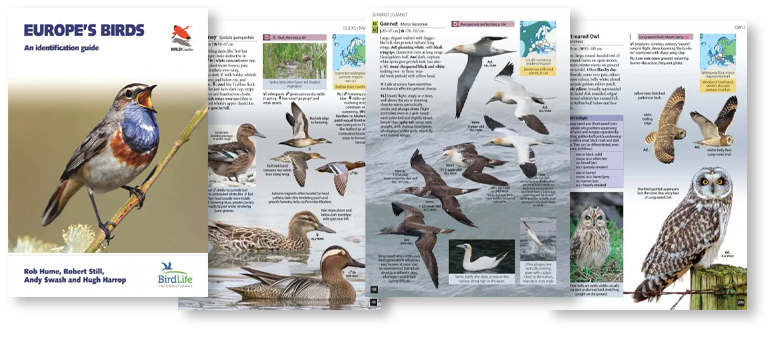

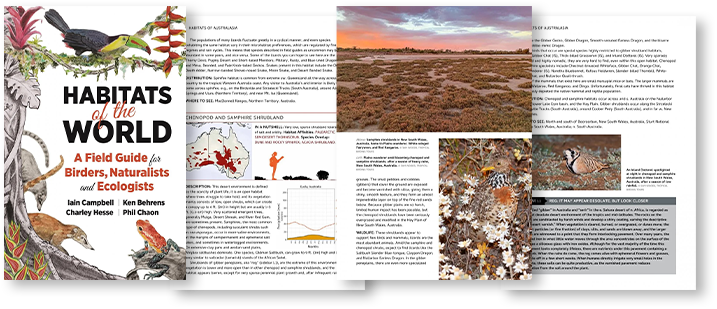

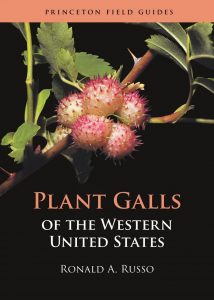

Princeton University Press was founded in 1905 as a nonprofit publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Originally publishing university documents and newspapers, such as the Princeton Alumni Weekly, Princeton University Press didn’t publish its first book until 1912. Since then, they have published over 21,000 works, including many award-winning titles. Princeton University Press publishes well-known series such as WILDguides, the high-quality, practical guides to many wildlife regions around the world, and Princeton Illustrated Checklists, which contain illustrations and concise text of all species in specific regions. They also publish and distribute Wild Nature Press, a natural history publisher that specialises in books on marine life.

Princeton University Press was founded in 1905 as a nonprofit publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Originally publishing university documents and newspapers, such as the Princeton Alumni Weekly, Princeton University Press didn’t publish its first book until 1912. Since then, they have published over 21,000 works, including many award-winning titles. Princeton University Press publishes well-known series such as WILDguides, the high-quality, practical guides to many wildlife regions around the world, and Princeton Illustrated Checklists, which contain illustrations and concise text of all species in specific regions. They also publish and distribute Wild Nature Press, a natural history publisher that specialises in books on marine life.

Plant Galls of the Western United States

Plant Galls of the Western United States

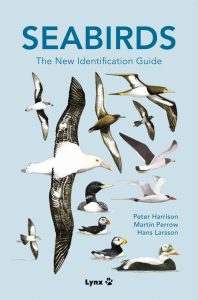

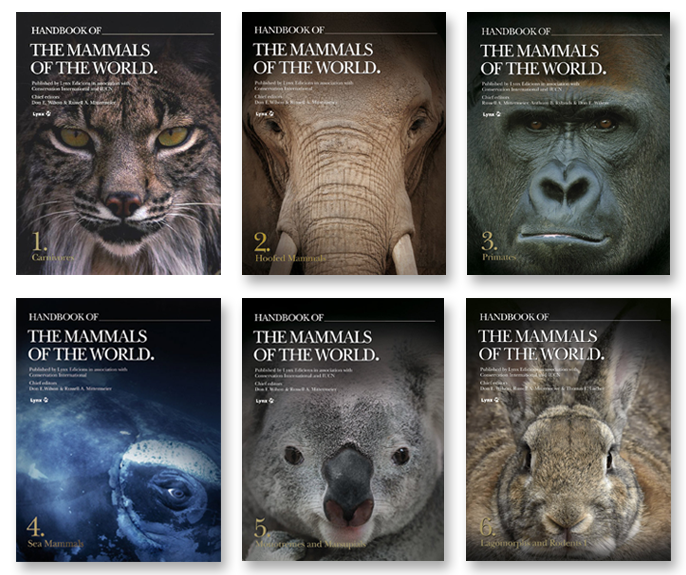

Lynx Edicions is a Barcelona-based publishing house, originally founded in 1989 to create the

Lynx Edicions is a Barcelona-based publishing house, originally founded in 1989 to create the

natural world and to human society. With an expert eye, Goulson skillfully guides the reader through different aspects of their importance, from the multi-million pound service that dung beetles provide the farming industry each year in the UK alone to the vital role that pollinators play in underpinning ecosystems across the planet, and the value that insects have in their own right as beautiful, vibrant denizens of our planet. The author’s passion is infectious; it is difficult to read this section without becoming invested in the wondrous ranks of the planet’s invertebrates, making the threat of their decline feel all the more personal.

natural world and to human society. With an expert eye, Goulson skillfully guides the reader through different aspects of their importance, from the multi-million pound service that dung beetles provide the farming industry each year in the UK alone to the vital role that pollinators play in underpinning ecosystems across the planet, and the value that insects have in their own right as beautiful, vibrant denizens of our planet. The author’s passion is infectious; it is difficult to read this section without becoming invested in the wondrous ranks of the planet’s invertebrates, making the threat of their decline feel all the more personal.  controversial among some parties. He consistently highlights the arguments of his critics, treating them with respect and validation. At some points he provides his rebuttal while at others he admits to the shortcomings of the relevant research, explaining why a different approach was impossible at the time. This is indicative of an attitude that permeates the book – the issues that he writes about are bigger than minor gripes with experimental methodologies, bigger than business margins or political leanings. He presents with a neutral eye the irrefutable reality that insects are vanishing at a terrifying rate, and unless action is taken the world is heading towards a very real disaster within generations. Though frequently distressing and at times heartbreaking, Goulson writes with a voice compelling and just witty enough to prevent the reader from becoming despondent. This book is not intended to drive us to despair, but to action.

controversial among some parties. He consistently highlights the arguments of his critics, treating them with respect and validation. At some points he provides his rebuttal while at others he admits to the shortcomings of the relevant research, explaining why a different approach was impossible at the time. This is indicative of an attitude that permeates the book – the issues that he writes about are bigger than minor gripes with experimental methodologies, bigger than business margins or political leanings. He presents with a neutral eye the irrefutable reality that insects are vanishing at a terrifying rate, and unless action is taken the world is heading towards a very real disaster within generations. Though frequently distressing and at times heartbreaking, Goulson writes with a voice compelling and just witty enough to prevent the reader from becoming despondent. This book is not intended to drive us to despair, but to action.  encouraging native plants in our towns and cities and overhauling the way in which we view farming. Finally, there is an extensive list of actions, large and small, that people can take, listed by occupation. This section is what the book has been building to, and it is worth reading for this alone. As usual, respect is paid to all viewpoints and all members of society. It doesn’t matter whether the reader is in a position where a free-range organic, locally sourced diet is financially viable or not – there will be other actions that they can take regardless of financial matters. Nor does it matter if they have beliefs, political or economic, that might conflict with the author’s. It is a call for society to overlook such matters which are, in the face of such a crisis, trivial.

encouraging native plants in our towns and cities and overhauling the way in which we view farming. Finally, there is an extensive list of actions, large and small, that people can take, listed by occupation. This section is what the book has been building to, and it is worth reading for this alone. As usual, respect is paid to all viewpoints and all members of society. It doesn’t matter whether the reader is in a position where a free-range organic, locally sourced diet is financially viable or not – there will be other actions that they can take regardless of financial matters. Nor does it matter if they have beliefs, political or economic, that might conflict with the author’s. It is a call for society to overlook such matters which are, in the face of such a crisis, trivial.