Now is the time of year when many bird species are starting to defend territories more noisily and to look for suitable nest sites. To coincide with National Nest Box Week (14th to 21st February), we have been busy selecting our favourite nest boxes, updating our advisory blog posts on where to site nest boxes and how to put them up, and installing our own nest box cameras at our warehouse in Devon.

At this time of year, the birds will currently be exploring nest sites and should start bringing nesting material into the boxes in the next couple of weeks.

Given that it has been a mild winter, the breeding season should start earlier this year, but we still would not expect the first eggs to appear until April. This means that there is still time to get a nest box up in your garden to provide much needed nesting space for birds. You could even consider enjoying this amazing spring spectacle up close with a nest box camera.

Choosing the nest boxes and cameras

We chose two of our Camera Ready Nest Boxes because they have a perspex panel in the side to let in extra light, which gives better daytime images in colour, and a camera clip on the lid. We then selected two of our most popular cameras, the WiFi Nest Box Camera, which can stream footage directly to a smartphone or tablet, and the IP Nest Box Camera, which can provide a live stream to a website. There are many options available when it comes to selecting a nest box camera, and our blog post on Watching Wildlife – How to choose the right Nest Box Camera can help you decide between the different options.

How to install the camera in the nest box

The procedure for attaching the camera to the lid was the same for the WiFi and IP cameras. We found that the easiest way of installing the camera into the box lid was to attach the camera bracket to the lid first and then to attach the camera to its bracket afterwards. We unscrewed the camera clip with a large Phillips screwdriver, slid the camera bracket underneath the clip on the inside of the lid and then tightened the clip screw back up again.

Then we attached the camera onto its bracket using a very small Phillips screwdriver.

With the WiFi camera we found that it was best to point the aerial downwards because our nest box roof was sloping. You can check the angle of the camera through the perspex panel on the side – it is best to have it pointing directly downwards and not angled. Ensure that the camera cable is running out of the notch on the back of the box so that the lid fits down snugly.

Putting up the nest boxes

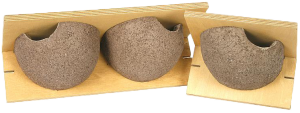

We sited the nest boxes on the eastern side of the building close to the tree cover along the river. To maximise the chances of occupation, it is advisable to site boxes for cavity nesting birds such as blue and great tits away from prevailing winds, and with a direct flight path to some tree cover. We attached them securely to the wall, approximately 2m off the ground – this is high enough to prevent interference but close enough to reach for monitoring and maintenance. We have put them as far apart as possible from each other and out of the sight of our bird feeder around the corner. We think that it may be unlikely that tit species would nest that closely to each other but if the boxes are occupied by house sparrows then these two boxes could form the start of a colony.

Connecting up the cameras

The IP Nest Box Camera connects via Ethernet cable directly into a router, hub or switch and then you need to choose software to allow you to access the camera feed and live stream to a website. We are currently trialling Anycam.iO. If there is no WiFi network, the WiFi camera can be used as a standalone WiFi source that you connect to directly with your smartphone or tablet. Alternatively you can tether the WiFi camera to your existing WiFi network and access it as a node on the network. The WiFi camera is viewed via an app on your smartphone or tablet and we are currently trialling ICSee Pro.

Now we just have to wait and hope that the local birds decide that these are desirable nesting sites! For further advice on nest boxes and cameras, please do not hesitate to contact our team of Wildlife Equipment Specialists.

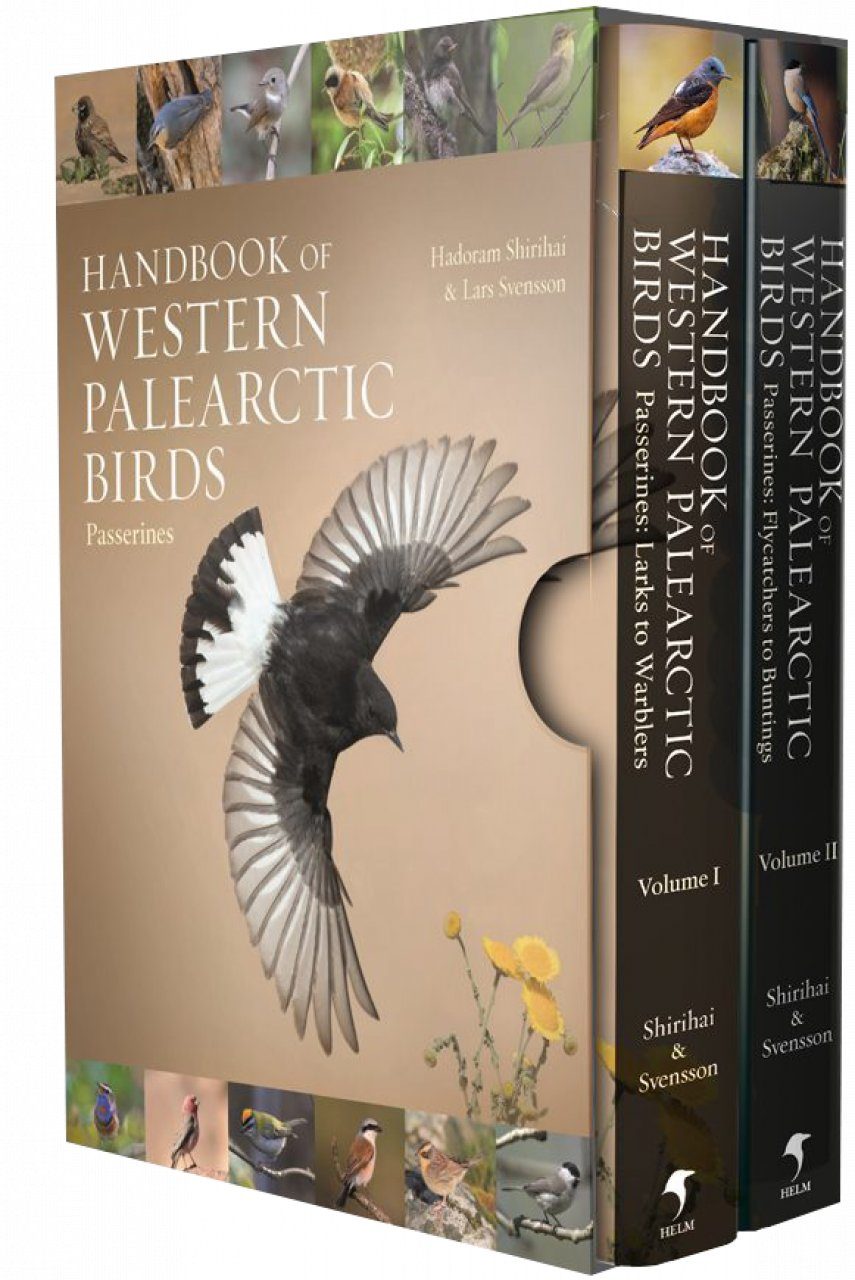

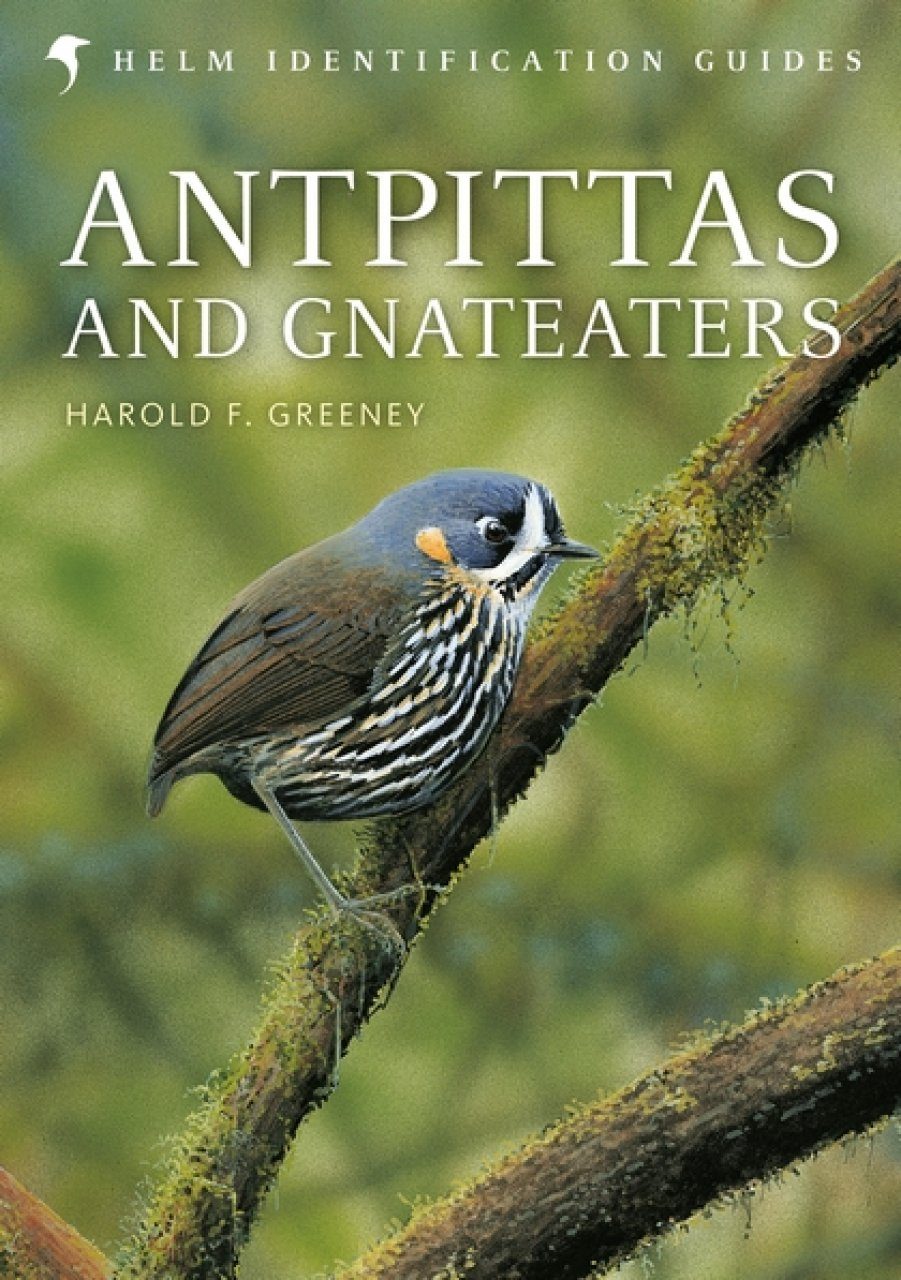

Recommended reading

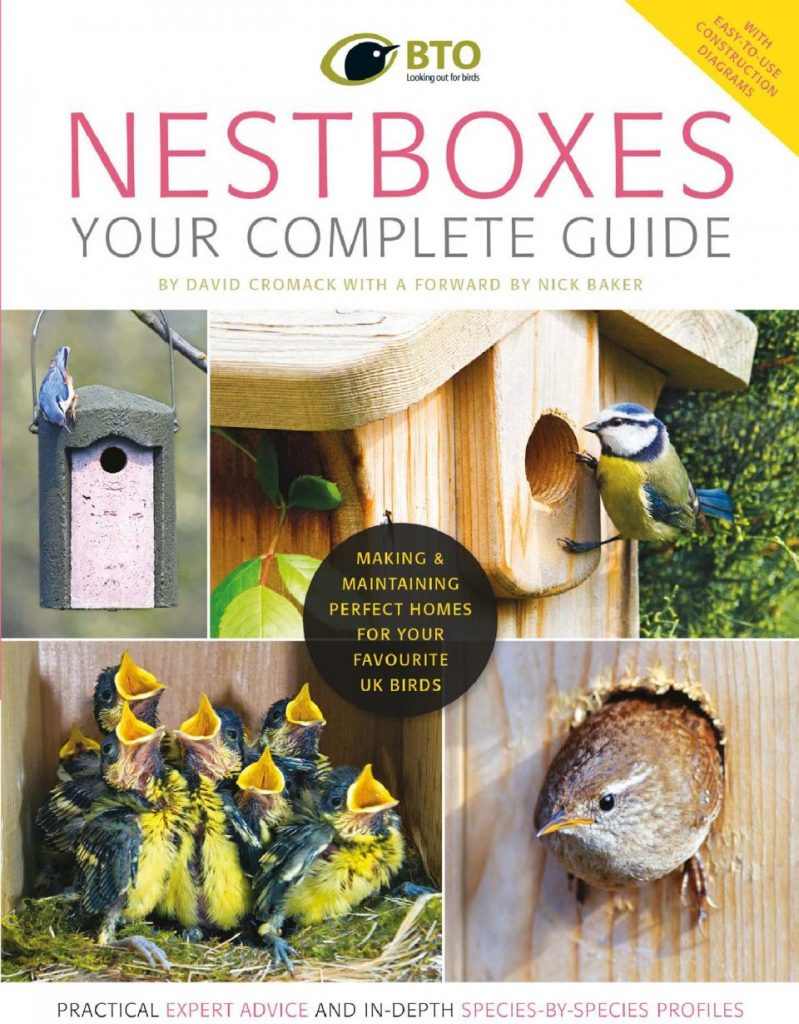

Nestboxes

Your Complete Guide

£10.95

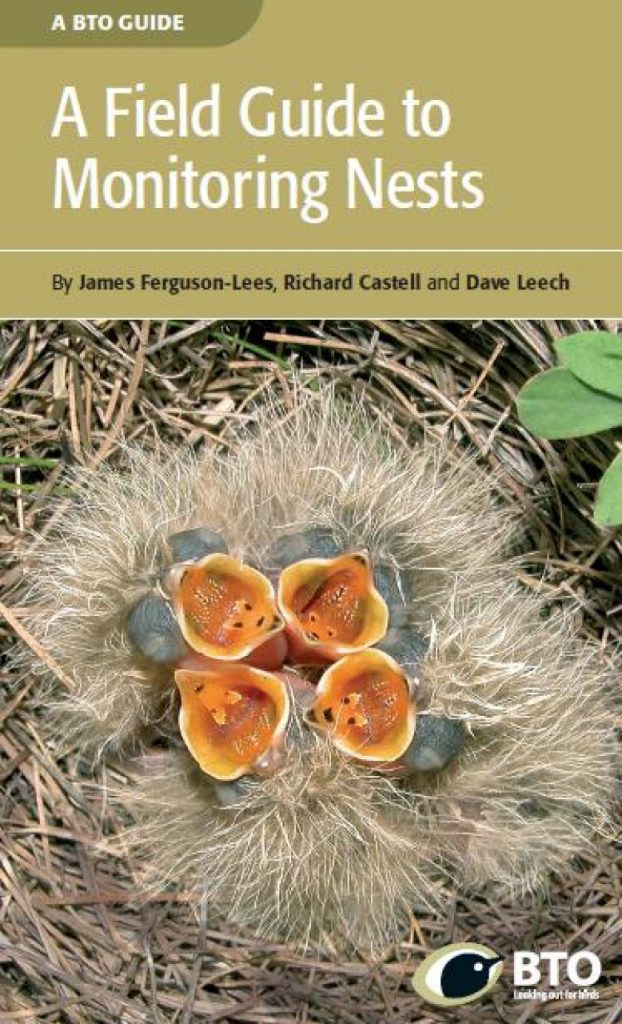

A Field Guide to Monitoring Nests

£24.99

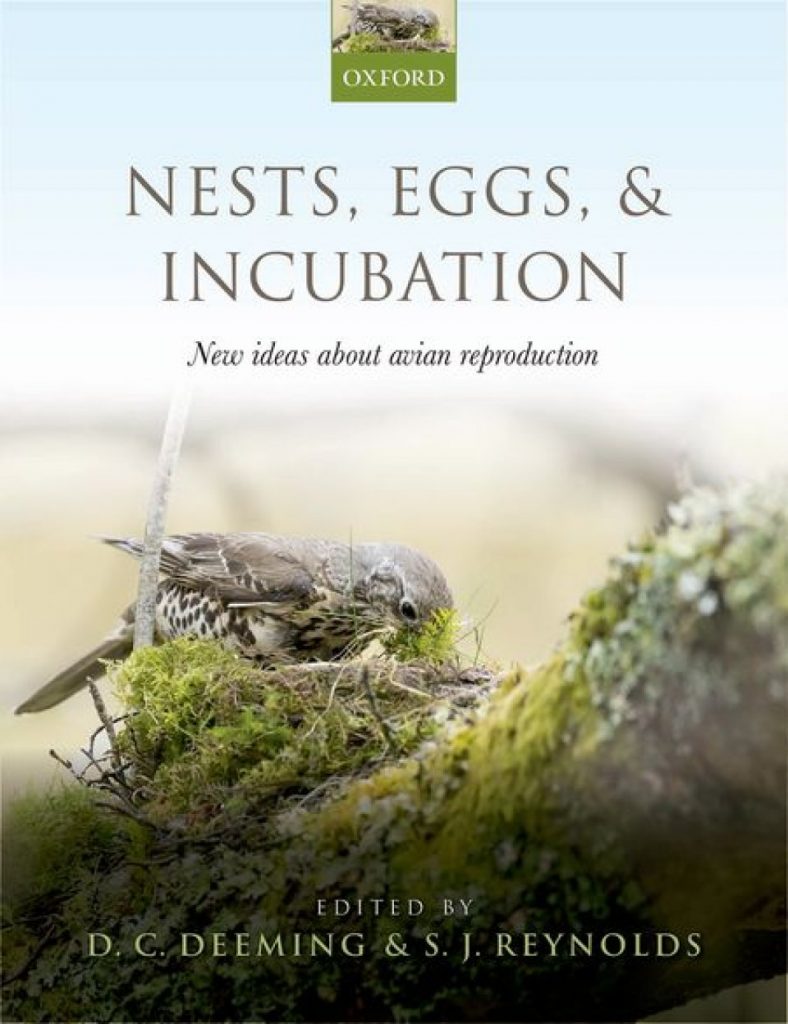

Nests, Eggs & Incubation

£23.99 £40.99

The Blue Tit

£49.99

Recommended Products

Nest Box Camera Kit

From £58.99

WiFi Nest Box Camera

£109.00 £129.00

IP Nest Box Camera

£100.00

Side Opening Nest Box

£29.95

Greeted by the trumpeting of elephants across the otherwise silent car park, we arrived at Chester Zoo. With a quick glimpse into the rhino enclosure, we turned away from the main entrance and headed towards the lecture theatre (passing an impressive and colourful bug hotel) for the start of the

Greeted by the trumpeting of elephants across the otherwise silent car park, we arrived at Chester Zoo. With a quick glimpse into the rhino enclosure, we turned away from the main entrance and headed towards the lecture theatre (passing an impressive and colourful bug hotel) for the start of the

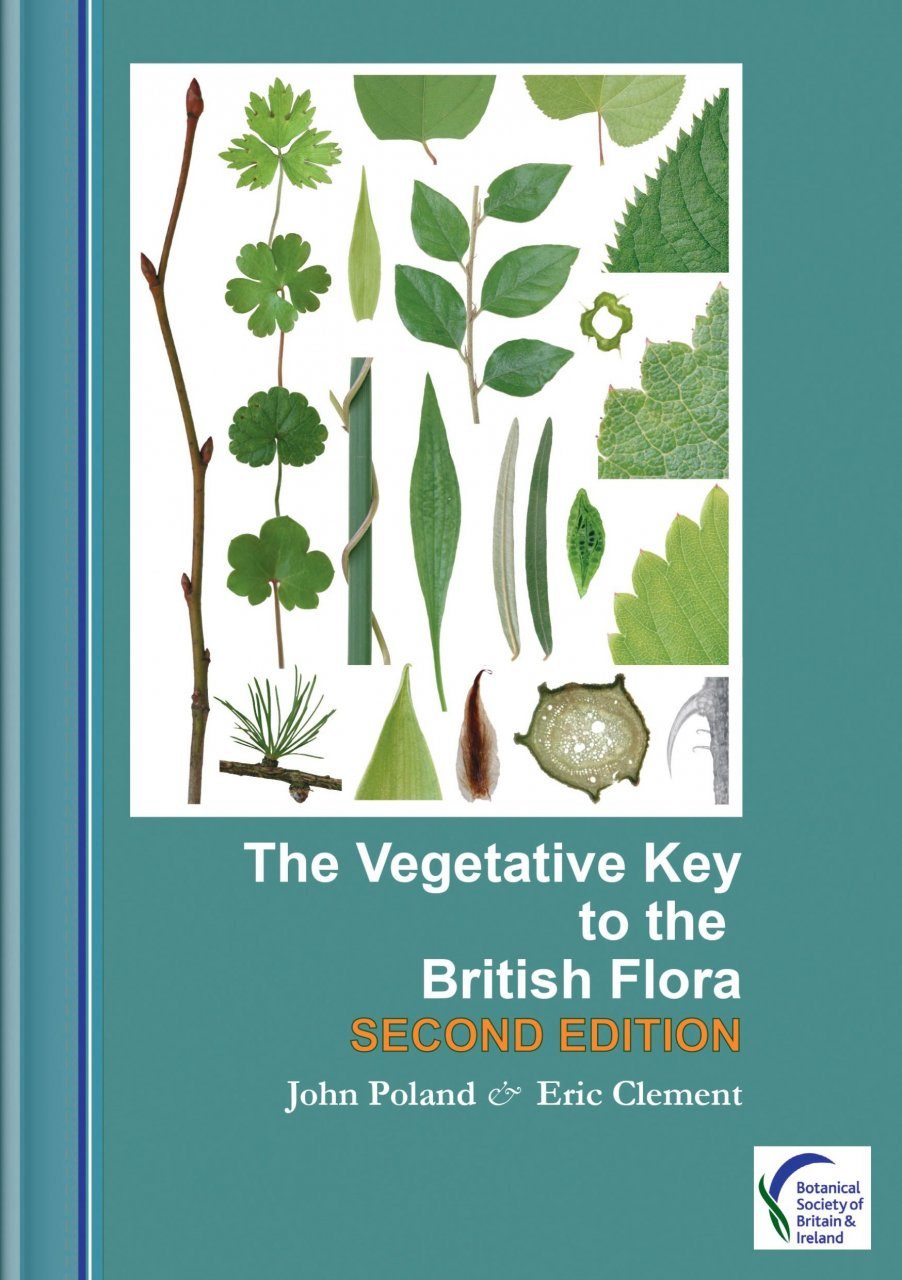

Why did you consider producing a second edition of The Vegetative Key to the British Flora and how long has it been in preparation?

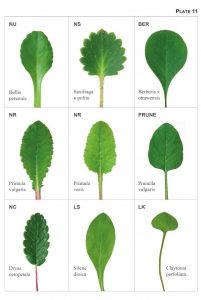

Why did you consider producing a second edition of The Vegetative Key to the British Flora and how long has it been in preparation? Is there one easy mistake that can be made when identifying plants in their vegetative state?

Is there one easy mistake that can be made when identifying plants in their vegetative state?