NHBS’s Top 10 bestsellers September 2021

We love looking back at our bestsellers from the month before and are very excited to share our Top 10 list for September.

This month, our bestsellers include exciting new works such as Europe’s Birds and Habitats of the World, as well as several ever-popular titles you may recognise from previous Top 10s, such as Secrets of a Devon Wood and Britain’s Insects.

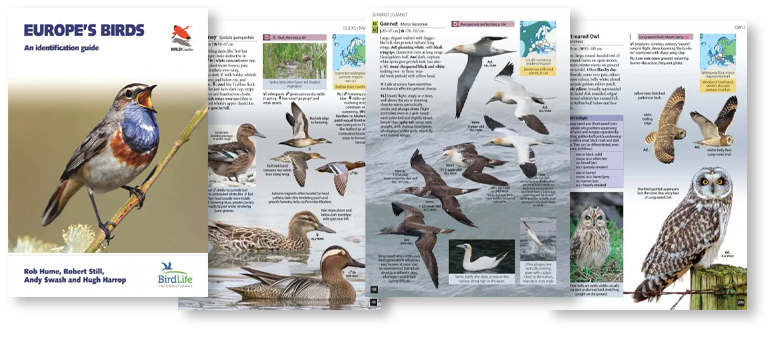

Europe’s Birds: An Identification Guide | Andy Swash et al

Hardback | August 2021

In top place this month is WILDGuides latest book Europe’s Birds. Covering more than 900 species and illustrated with over 4,700 photographs, this is the most comprehensive, authoritative and ambitious single-volume photographic guide to Europe’s birds ever produced. Birdwatchers of any ability will benefit from the clear text; details on range, status and habitat; and an unrivalled selection of photographs.

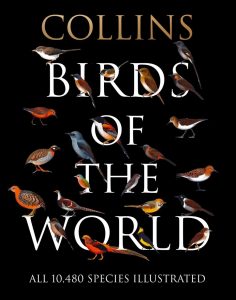

Collins Birds of the World: All 10,711 Species Illustrated | Norman Arlott et al

Hardback | September 2021

Collins Birds of the World is the complete collection of the Collins Field Guide‘s incredibly detailed, accurate and beautiful bird paintings, brought together for the first time in one comprehensive volume. All 10,711 of the world’s bird species are covered – this is the ultimate reference book for birdwatchers and bird enthusiasts.

Read our interview with Norman Arlott.

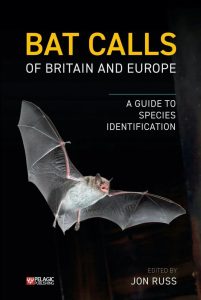

Bat Calls of Britain and Europe: A Guide to Species Identification| Jon Ross et al

Hardback | August 2021

Bat Calls of Britain and Europe is a comprehensive guide to the calls of the 44 species of bat currently known to occur in Europe, drawing on the expertise of more than 40 specialist authors. Aimed at volunteers and professionals alike, topics include the basics of sound, echolocation in bats, an introduction to acoustic communication and call analysis. Detailed information is provided for each species on their distribution, emergence, flight and foraging behaviour, habitat, echolocation calls – including parameters of common measurements – and social calls.

Bat Calls of Britain and Europe is a comprehensive guide to the calls of the 44 species of bat currently known to occur in Europe, drawing on the expertise of more than 40 specialist authors. Aimed at volunteers and professionals alike, topics include the basics of sound, echolocation in bats, an introduction to acoustic communication and call analysis. Detailed information is provided for each species on their distribution, emergence, flight and foraging behaviour, habitat, echolocation calls – including parameters of common measurements – and social calls.

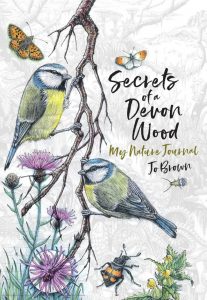

Secrets of a Devon Wood: My Nature Journal | Jo Brown

Hardback | October 2020

Secrets of a Devon Wood is a hymn to the intricate beauty of the natural world. Artist and illustrator Jo Brown started keeping her nature diary in a bid to document the small wonders of the wood behind her home in Devon. This book is an exact replica of her original black Moleskin journal, a rich illustrated memory of Jo’s discoveries in the order in which she found them.

Secrets of a Devon Wood is a hymn to the intricate beauty of the natural world. Artist and illustrator Jo Brown started keeping her nature diary in a bid to document the small wonders of the wood behind her home in Devon. This book is an exact replica of her original black Moleskin journal, a rich illustrated memory of Jo’s discoveries in the order in which she found them.

Jo very kindly agreed to answer some of our questions for a Q&A. Read the full interview here.

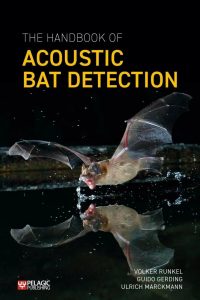

The Handbook of Acoustic Bat Detection | Volker Runkel

Paperback | September 2021

A recent release, The Handbook of Acoustic Bat Detection provides an in-depth understanding of acoustic detection principles, study planning, data handling, properties of bat calls, manual identification of species, automatic species recognition, analysis of results, quality assurance and the background physics of sound.

A recent release, The Handbook of Acoustic Bat Detection provides an in-depth understanding of acoustic detection principles, study planning, data handling, properties of bat calls, manual identification of species, automatic species recognition, analysis of results, quality assurance and the background physics of sound.

Read our interview with the authors.

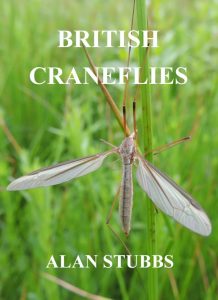

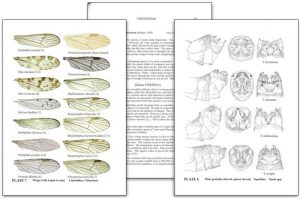

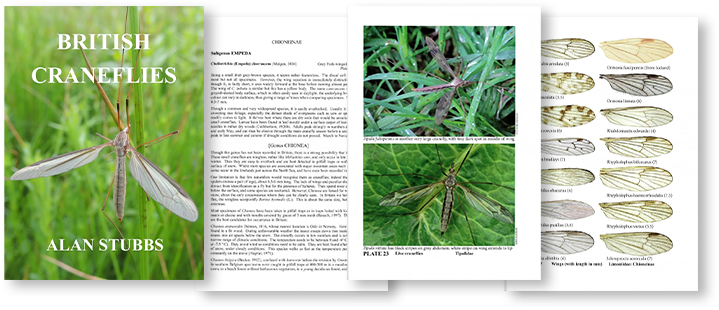

British Craneflies | Alan Stubbs

Hardback | July 2021

British Craneflies is a guide to the identification and natural history of 250 species in six families of cranefly. It describes the distribution and habitat of each one, with 128 pages of identification keys illustrated with thumbnail drawings and colour plates showing the wing venation and markings of 180 species. This guide also contains photograph examples of some distinctive and common craneflies, illustrations of the male genitalia for all species of Tipulidae and for most genera of other families, and introductory chapters including a full account of the enemies of craneflies.

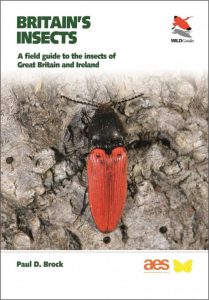

Britain’s insects: A Field guide to the insects of Great Britain and Ireland | Paul D. brock

Flexibound | May 2021

Britain’s Insects makes the Top 10 list again this month! This field guide is an innovative, up-to-date, carefully designed and beautifully-illustrated field guide to Britain and Ireland’s 25 insect orders, concentrating on popular groups and species that can be identified in the field.

Featuring superb photographs of live insects, Britain’s Insects covers the key aspects of identification and provides information on status, distribution, seasonality, habitat, food plants and behaviour.

Silent Earth: Averting the Insect Apocalypse | Dave Goulson

Hardback | August 2021

Silent Earth is part love letter to the insect world, part elegy, and part rousing manifesto for a greener planet. Drawing on the latest ground-breaking research and a lifetime of study, Silent Earth reveals the shocking decline of insect populations that has taken place in recent decades, with potentially catastrophic consequences.

British Moths: A Gateway Guide | James Lowen

Spiralbound | September 2021

British Moths is a wonderful introduction to 350 species of the most common and eye-catching adult moths that you may encounter in the UK. Concise species accounts include information on key features, seasonality, and when and where to see them. Each account is also placed alongside photos that have been carefully chosen to aid identification with clearly marked top tips.

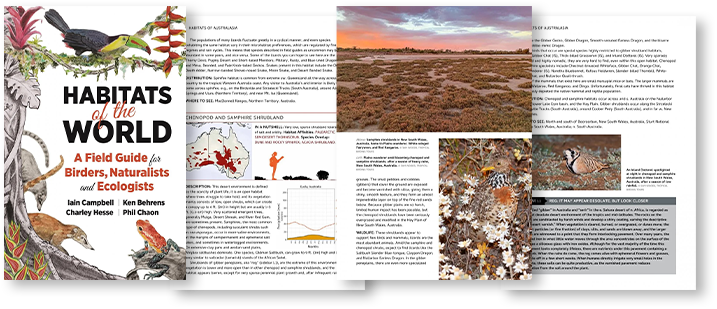

Habitats of the World: A Field Guide for Birders, Naturalists, and Ecologists | Iain D Campbell Et al

Flexibound | September 2021

Habitats of the World is the first field guide to the world’s major land habitats – 189 in all. Using the format of a natural history field guide, this comprehensive book features concise identification descriptions and is richly illustrated, including more than 650 colour photographs of habitats and their wildlife, 150 distribution maps, 200 diagrams and 150 silhouettes depicting each habitat alongside a human figure, providing an immediate grasp of its look and scale.

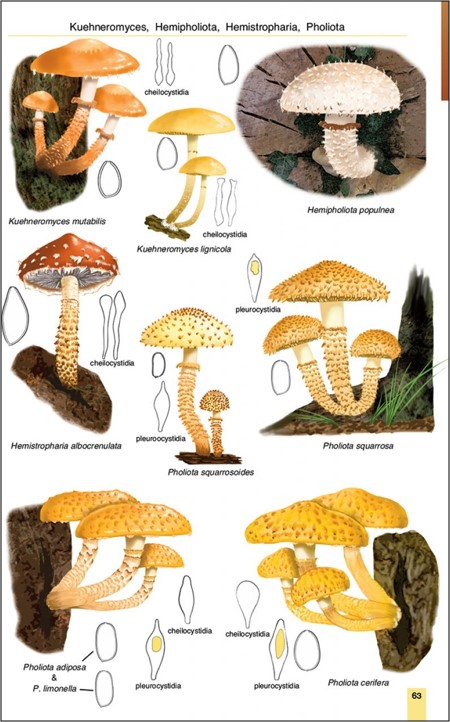

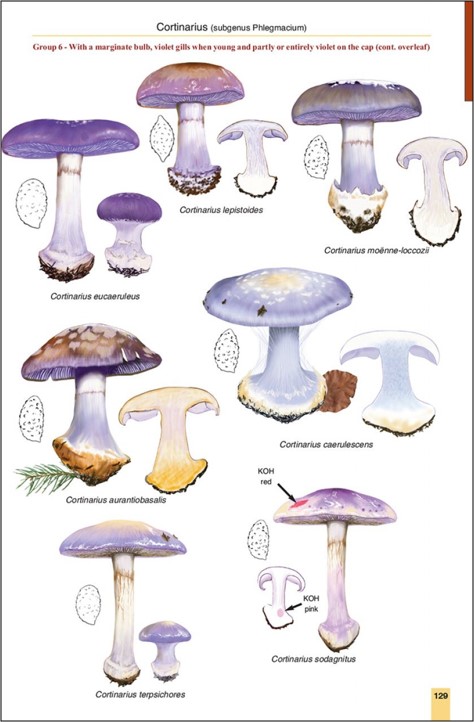

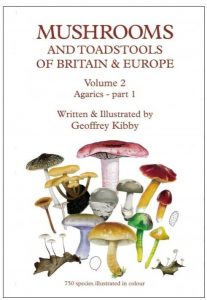

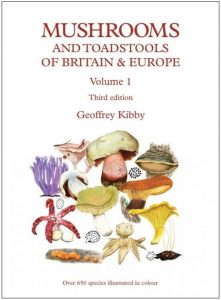

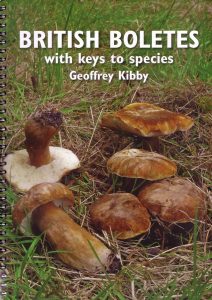

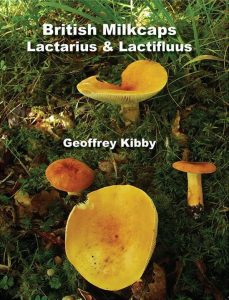

Geoffrey Kibby is one of Britain’s foremost experts on identifying mushrooms in the field, and his privately published books on how to identify British mushrooms pass on many of those skills. Kibby’s user-friendly books contain an enormous amount of information, are fully illustrated and are aimed at everyone, from the fungi enthusiast to the expert mycologist. The wealth of detail includes vital features to look for when identifying wild mushrooms and the important identification characteristics when using a microscope, often an essential tool in mycology.

Geoffrey Kibby is one of Britain’s foremost experts on identifying mushrooms in the field, and his privately published books on how to identify British mushrooms pass on many of those skills. Kibby’s user-friendly books contain an enormous amount of information, are fully illustrated and are aimed at everyone, from the fungi enthusiast to the expert mycologist. The wealth of detail includes vital features to look for when identifying wild mushrooms and the important identification characteristics when using a microscope, often an essential tool in mycology. I was 13 when I first became aware of fungi: an intensely violet toadstool, unlike anything I had ever seen (Laccaria amethystina) and from that moment, I was hooked. I bought my first little mushroom guide, then another and another and more through the years until my bookshelves started to groan under the weight of books about fungi. Now, more than 50 years later, I am writing my own books, trying to produce the sort of works that I would have wanted as an aspiring young mycologist. My books are based on my years in the field, hopefully capturing the essence of each species. I have also made a conscious point of illustrating species not readily available in other guides and trying to give the most up-to-date names in what is an ever-changing science. Mycology is an inexhaustible field of study at whatever level your interest lies. With over 4000 species of larger fungi in Britain, you will never run out of species to find or new facts to discover.

I was 13 when I first became aware of fungi: an intensely violet toadstool, unlike anything I had ever seen (Laccaria amethystina) and from that moment, I was hooked. I bought my first little mushroom guide, then another and another and more through the years until my bookshelves started to groan under the weight of books about fungi. Now, more than 50 years later, I am writing my own books, trying to produce the sort of works that I would have wanted as an aspiring young mycologist. My books are based on my years in the field, hopefully capturing the essence of each species. I have also made a conscious point of illustrating species not readily available in other guides and trying to give the most up-to-date names in what is an ever-changing science. Mycology is an inexhaustible field of study at whatever level your interest lies. With over 4000 species of larger fungi in Britain, you will never run out of species to find or new facts to discover.

Recently added to our range, the

Recently added to our range, the

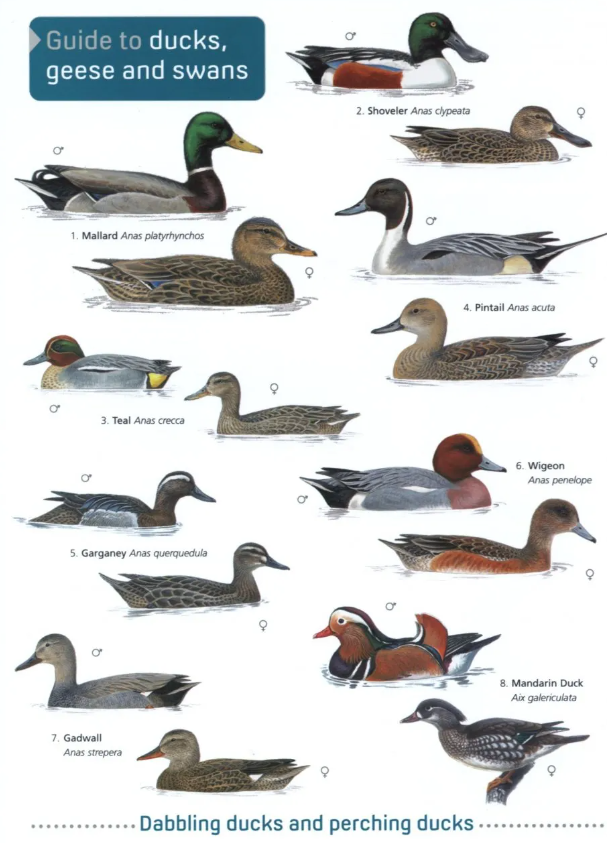

Guide to Ducks, Geese and Swans

Guide to Ducks, Geese and Swans  RSPB Spotlight: Ducks and Geese

RSPB Spotlight: Ducks and Geese