The Batlogger S2 is a compact passive recorder manufactured by Elekon. This all-in-one static bat detector and ultrasonic recorder is designed to be left unattended in the field over several nights to survey and monitor bats. The S2 is operated solely via Bluetooth and the BATLOGGER Control App (available on iOS and Android). It is small, weighing only 138g and measuring 132 x 72 x 35mm, but despite its size, the S2 is robust. It is waterproof and replacement microphones are also available, handy if the original microphone becomes damaged or loses sensitivity.

Elekon has designed the S2 to be easy to use and lightweight, and built to withstand fieldwork conditions. We took the opportunity on a warm evening in mid-May to test the S2’s ability.

How we tested

The S2 was set up in a hedgerow in South Devon, close to a small known roosting site.

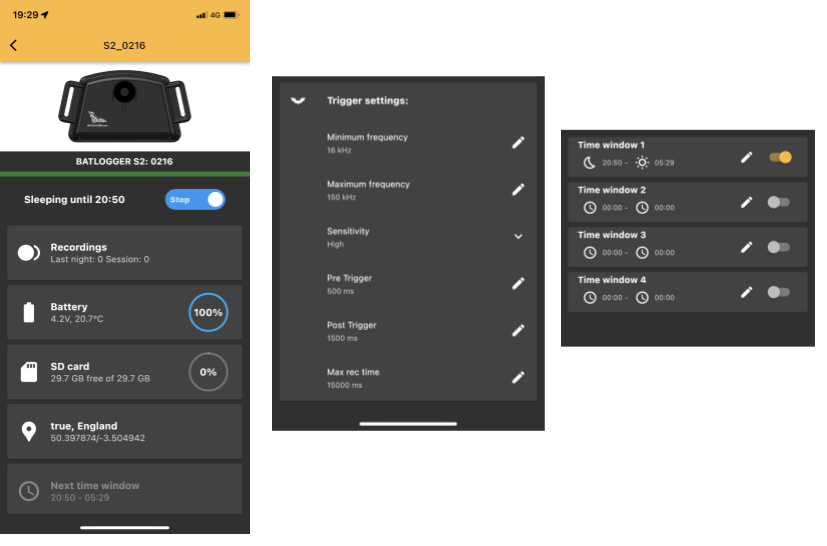

We connected the S2 to the BATLOGGER Control App on an iPhone via Bluetooth. Once connected, the S2 determines the dusk and dawn times using the GPS location from the phone/tablet, and suggests these as automatic trigger times. We selected this automatic time window, but, you can choose and customise your own and set multiple time windows as needed.

The S2 is full spectrum with a range of 10-150kHz and a sample rate of 312.5 kHz. The default sensitivity is balanced, and we adjusted the sensitivity to ‘high’ using the App. This may lead to several unwanted calls in busier environments; however, it also ensures that it is triggered by most types of bat call, including social calls, which can sometimes be missed.

Once collected from the field after one night of deployment, the recordings were downloaded from the S2 to a computer using the USB-C to USB-C cable (if you do not have a USB-C port, you’ll need an adaptor). Helpfully, the S2 is charged using the same USB-C cable – a single charge provides 100 hours of power!

The recordings are stored on an internal microSD card, and the S2 generates two file types: an audio file (.wav) and a recording information file (.xml). The audio files allow you to listen to your recordings through bat call analysis software and the information files store important metadata such as date, location, recording time, and device settings.

What we found

The BATLOGGER Control App shows you the number of sessions recorded – the high sensitivity triggered 192 audio files over one night. We used the BatExplorer software to manage and view the S2 recordings. The software has key features such as automatic bat call detection, making sorting files very easy, and it also provides suggestions for species identification.

Of the 192 audio files, 40 of these identified the common pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus). The default S2 sensitivity is ‘balanced’, this may have led to a smaller number of unwanted files (which recorded sounds other than bats). But we did not want to miss a bat call and the BatExplorer software allows you to quickly filter the unwanted files.

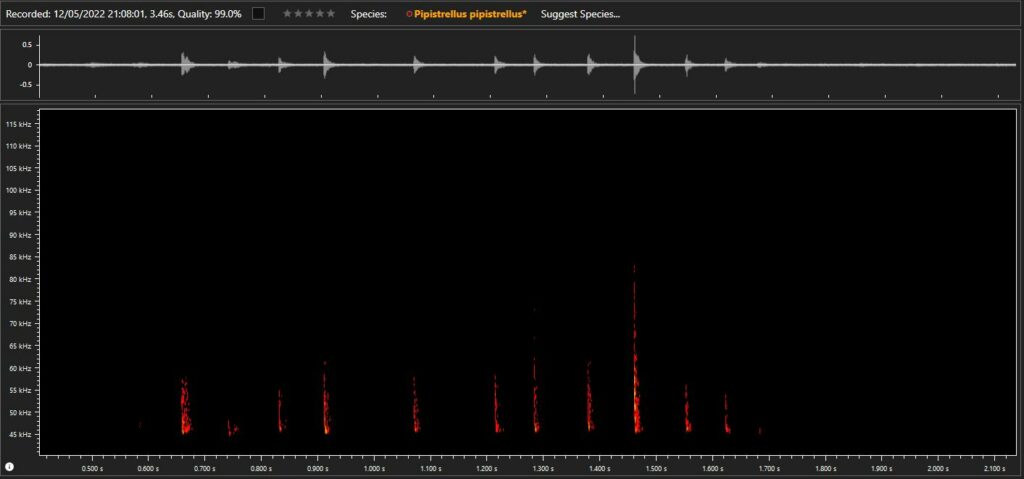

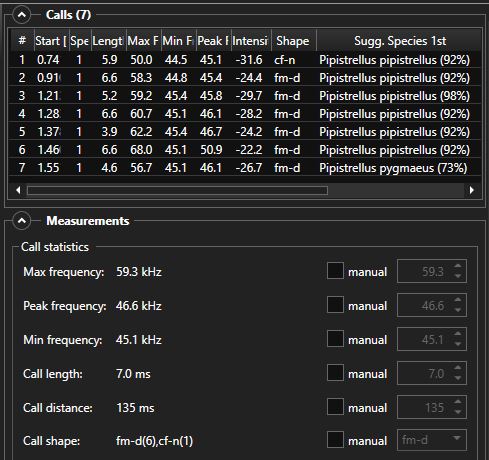

The echolocation frequency for common pipistrelles is approximately 45kHz, and the below images show an example of the spectrogram and call measures from a common pipistrelle recording taken at dusk and the information popout that BatExplorer produces, detailing the automatic analysis that the software carries out.

Below is an audio clip with its accompanying spectrogram of a common pipistrelle taken at dusk. The BatExplorer software allows you to customise the playback and how the spectrogram can be viewed.

Our opinion

The physical design and key features of the S2 makes surveying bats a simple task.

The S2 truly is discrete and lightweight, making it easy to set up in the field, and once deployed the battery life will allow up to 10 (10 hour) consecutive nights of surveying.

The setup through the BATLOGGER Control App is straightforward. The S2 conveniently uses the GPS location on your phone/tablet to determine dusk and dawn which benefits the accuracy of the recording schedules. You can choose your settings at a click of a button, and the instruction manual is clear and accessible for any help needed.

The only limitation we found is that you cannot access the recordings straight from the App. However, transferring the files across to your computer allows you to listen to and analyse the audio files with ease. The BatExplorer software (available on a 30-day free trial) enhances analysis as it allows you to review, manage, and organise your recordings.

The S2 is an impressive bat detector, and it is an ideal choice for professionals and ecological surveyors.

The Elekon Batlogger S2 can be found here. Our full range of passive full spectrum bat detectors can be found here.

If you have any questions about our range or would like some advice on the right product for you then please contact us via email at customer.services@nhbs.com or phone on 01803 865913.