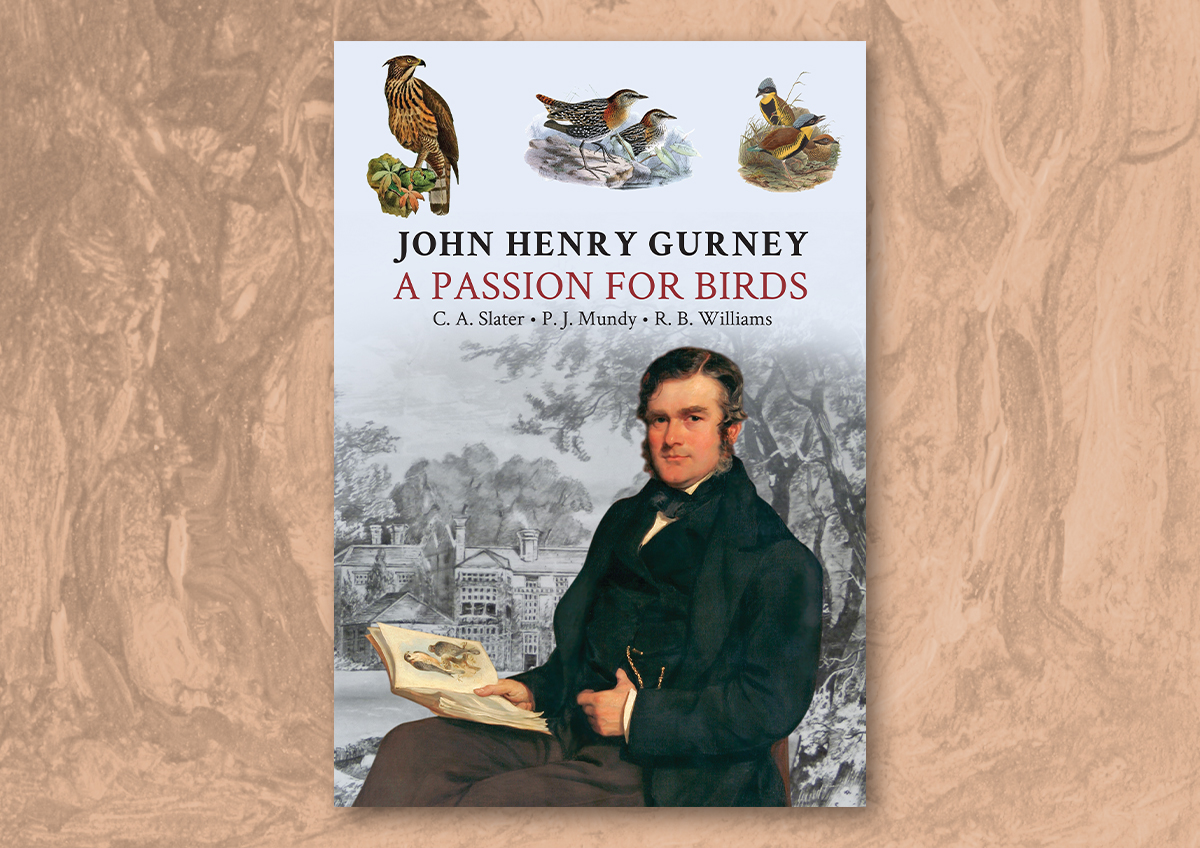

Many books have been written about notable names in the world of natural history, with the likes of Darwin and Wallace being the first that come to mind. Digging a little deeper in areas such as ornithology will uncover names that aren’t as well known and yet still made significant contributions to the field. Uncovering almost 30 species of birds that were previously unknown to science, John Henry Gurney was a founding member of the British Ornithologists’ Union in 1859, while focusing on the identification of birds of prey. Large collections of letters written by Gurney to Alfred Newton are held by Norfolk County Council in the Norfolk Archive Centre, and others to his family members are in the Library of the Society of Friends in Euston, London. Now a deeply researched biography about the man, his personal life and his contributions to cataloguing nature is being published by John Beaufoy Publishing.

Many books have been written about notable names in the world of natural history, with the likes of Darwin and Wallace being the first that come to mind. Digging a little deeper in areas such as ornithology will uncover names that aren’t as well known and yet still made significant contributions to the field. Uncovering almost 30 species of birds that were previously unknown to science, John Henry Gurney was a founding member of the British Ornithologists’ Union in 1859, while focusing on the identification of birds of prey. Large collections of letters written by Gurney to Alfred Newton are held by Norfolk County Council in the Norfolk Archive Centre, and others to his family members are in the Library of the Society of Friends in Euston, London. Now a deeply researched biography about the man, his personal life and his contributions to cataloguing nature is being published by John Beaufoy Publishing.

NHBS managed to bring the co-authors together to answer a few questions about the book and uncovering the history of a man seemingly forgotten by the world of ornithology.

How did you first come across John Henry Gurney, and why did you decide to write this biography?

As co-authors of this biography, we (Clive Slater, Peter Mundy and Ray Williams) have combined our three quite different perspectives of John Henry Gurney. Almost 50 years ago, Ray commenced research on a bio-bibliography of the Victorian publisher John Van Voorst (1804-1898) and has published many accounts of the books that Van Voorst produced. One of them, in 2008, concerned Gurney’s Descriptive Catalogue of the Raptorial Birds in the Norfolk and Norwich Museum – Part I. Discovering that Gurney was occupied from 1857 to 1864 in producing Part I but that he never completed the project prompted the obvious question of “why?” Further investigations revealed his misfortunes of the 1860s, including his wife’s elopement, an inevitable divorce, and his entanglement in the notorious financial crash of Overend & Gurney for which the directors were tried for fraud (but acquitted).

When Peter was studying vulture specimens in the bird collection at the Natural History Museum at Tring for his PhD, he noticed some with Norwich Castle Museum labels. Then, much later, having bought a copy of Gurney’s 1884 account of raptors in the Norfolk and Norwich Museum, he realised what a huge collection it must have once been. He asked Clive, his ornithologist friend from university days in the 1960s and now a Norwich resident, to investigate. Apparently, none of the original specimens were present, which sparked their quest to discover more about Gurney and the fate of his remarkable collection. Since so little of his work seemed to have been remembered, Peter and Clive decided that it deserved wider recognition and so set about writing a biography. Since Ray’s 2008 paper on Gurney’s Descriptive Catalogue of the Raptorial Birds had come to Clive’s attention, contact was made, and thus came about our decision to join forces, Clive and Peter contributing as ornithologists, and Ray as a historian and bibliographer.

For those unfamiliar with Gurney, could you briefly tell us a bit about him and his work?

Gurney was born in 1819 and raised among the famous Norfolk family of wealthy Quaker bankers, also well known as philanthropists or promulgators of the Quaker faith, not only in Britain, but also in America. After education at a Quaker school, he entered the family bank in Norwich. He had started collecting bird specimens from an early age and this interest developed into journal publications. From 1853, he made collecting and writing about raptors his speciality. Simultaneously, he was receiving and publishing on bird specimens supplied by collectors in southern Africa. These two threads dominated his life’s ornithological work. However, John Henry fell for a cousin, Mary Jary Gurney who was an Anglican, and he was therefore, upon his marriage to her, disowned by his co-religionists, as was the current Quaker convention.

Nevertheless, he did not abandon the principles of his upbringing and was assiduous in his commitments to his banking career, his public service as an MP and JP and his philanthropy. Though his additional personal ornithological research resulted in a constant and considerable workload, what is truly astonishing is his determination and strength of mind in continuing his bird work throughout a series of tragic misfortunes during the 1860s. His research procedures were constant throughout his life, meticulously documenting external morphology of as many specimens as possible, while accurately recording geographical distributions. He was not a theorist, however, and dealt only in facts as he recorded them. Although best known for his studies of the world’s birds of prey, Gurney’s wide zoological interests also embraced the birds, fishes, amphibians, reptiles, mammals and marine invertebrates of his home county of Norfolk, which he supplemented with fascinating accounts of historical manuscripts.

What were the greatest challenges you faced when writing this biography?

The research itself was, of course, naturally difficult and time consuming, involving numerous visits to libraries, archives and museums by all of us. The access to archival material in private and public collections of books and specimens in the UK and southern Africa was challenging and required much logistic planning. Covid lockdowns hampered access to libraries and museum collections. On several occasions when reviewing progress, we found that the vast amount of information gleaned had to be severely edited in order to keep below the agreed word limit.

A significant challenge, therefore, was not any difficulty in finding enough information, but was how to select the most important facts and to present them in the most succinct fashion. Moreover, information had to be continually assessed and corroborated, which additionally involved the interpretation and explanation of events, extending in the end to nine years since we decided in 2016 to combine resources. However, the major issue was Peter’s deteriorating health, leading to his death in February 2023. Nevertheless, his determination to continue contributing to our work despite his serious illness was inspirational and we vowed to finish the book as a testament to his courage (the book is also dedicated to him).

This book covers the intriguing twists and turns of Gurney’s life in impressive detail. Were there any discoveries that surprised you when researching this book?

Much taxonomic information was encountered, though that is practically certain to arise in any biography of a Victorian naturalist. It is significant, however, how deeply respected he was in the ornithological circles of his day – many others across the world would often seek his help and advice in their studies. But perhaps the most surprising revelations concern Gurney’s private life and how he miraculously managed to continue his ornithological research in the face of so much adversity and personal tragedy, all of which became intertwined with other misfortunes of his wider Norfolk family. These discoveries provided the answers that Ray sought to explain the slow progress of the Descriptive Catalogue of the Raptorial Birds and the failure to complete it. Whilst the Overend & Gurney affair has been known about for some years, we were able to add some more detail. Most startling of all was the story of Gurney’s wife’s elopement and its tragic impact not only on his own life, but his whole family, and British and American Quakers in general.

The American newspaper press was gleeful in their cruel and unjustifiable use of the unfortunate event for their own political purposes. Gurney must have been deeply embarrassed by the public exposure of these events, hence his self-exile from Norfolk for five years. However, the care he bestowed on his sickly younger son was exemplary and his ability to continue his bird studies whilst living out of a suitcase for years was quite extraordinary. Equally impressive was his memory of details of his specimens at that time, even when he could not access them. He apparently never saw his recalcitrant wife again, but as it happened, she possessed huge financial resources of her own and thus Mary Jary and her lover were ultimately able, after their marriage, to re-establish themselves in society with very little trouble. However, their family also was to be visited again by tragedy when Mary died of cancer, aged 43, and their daughter died of a brain disease, aged 31.

I was surprised to learn that although Gurney donated 1,300 foreign bird specimens to the Lynn Museum, sadly, none of them remain. What specimens would you have been most interested in seeing?

Of course, all the specimens were valuable historically but most exciting would have been a view of the collection from Alfred Russel Wallace’s travels in the Malay Archipelago, as these would have been special and we do not even know what they were! Also intriguing would have been sight of the central displays of birds of paradise and hummingbirds that must have been striking but we have no idea what they looked like.

There are currently seven recognised bird species named in Gurney’s honour. Do you have a personal favourite?

Yes, a great favourite of Clive’s is Gurney’s Eagle, Aquila gurneyi 1860. More than 160 years after George Robert Gray honoured Gurney with its name we still know very little about the biology of this species – nobody has reported even finding a nest! An attempt to see it in Halmahera in 2017 was frustrating for the only fleeting, distant views. For such a large, imposing eagle to be so elusive and little known is quite remarkable.

Despite his vast contributions, including describing 29 birds, 21 of which are still recognised today, John Henry Gurney seems to be somewhat forgotten by modern ornithology. Why do you think this is?

Since Victorian times, momentous scientific advances have been made and the world’s environment is rapidly changing beyond all recognition. In the biosciences, there has been for a century or more an increasing trend for research to become focused on ecology, biodiversity, migration, physiology, biochemistry, genetics and climatology, all of which are now crucial for understanding and combatting the threats of global warming and habitat destruction. Whilst taxonomy must underpin these trends, so that biologists are able to confidently identify whole organisms of animals and plants of importance, the emphasis on taxonomy per se has shifted from the Victorian obsession with finding and naming new species for its own sake. Thus, Gurney is only one of many hundreds of naturalists of his period now unknown to modern biologists in general.

Even Peter, a modern authority on raptors and southern African birds, was baffled as to why for so long he knew little about Gurney, who published nothing about himself and only one very small booklet aimed at the public to serve as a guide to his raptorial collection. Difficult to trace were his letters and other manuscripts, widely scattered among collections in the Natural History Museum in Tring, the Castle Museum in Norwich, the Barclays Group Archives in Manchester, and the Society of Friends’ Library in London. Perhaps if his planned book of raptor paintings by Joseph Wolf had come to fruition he would have become better known. But it seems strange that most world birders and conservationists are so familiar with his name via the beautiful but near-extinct Gurney’s Pitta.

How would you describe Gurney’s impact on ornithology?

Gurney helped lay the foundations of modern ornithology in Victorian times by supporting the fledgling British Ornithologists’ Union and their journal, Ibis, in which he published his papers on raptors and southern African birds, embellished by Joseph Wolf’s illustrations. By his descriptions of new raptorial species and records of worldwide geographical distribution of many species he contributed crucial information to the difficult study of raptors, still a perplexing group. We should also recognise the lasting value of his specimens to modern scholars and the support that he provided to other ornithologists in his day.

What are you working on next? Do you have any more writing projects lined up?

Clive continues researching the history of the bird collections that were once held at Norwich Castle Museum but were dispersed in the 1950s, at the same time as Gurney’s raptorial collection. Thousands of bird specimens were sold, loaned or given to other institutions. Some of them emanated from important expeditions and notable naturalists, so why were these collections at Norwich in the first place, what went where, and why?

Now that Ray’s work on Gurney is finished, he is returning to his project of the bio-bibliography of John Van Voorst, and after that, a similar study is envisaged of the life of Thomas Alan Stephenson (1898-1961), a sea-anemone taxonomist and expert on marine intertidal zonation, as well as a superb botanical and zoological artist whose beautifully accurate paintings give the impression of being colour photographs.

John Henry Gurney – A Passion for Birds is published by John Beaufoy Publishing in association with the British Ornithologists’ Club, and is available in hardback from NHBS here.

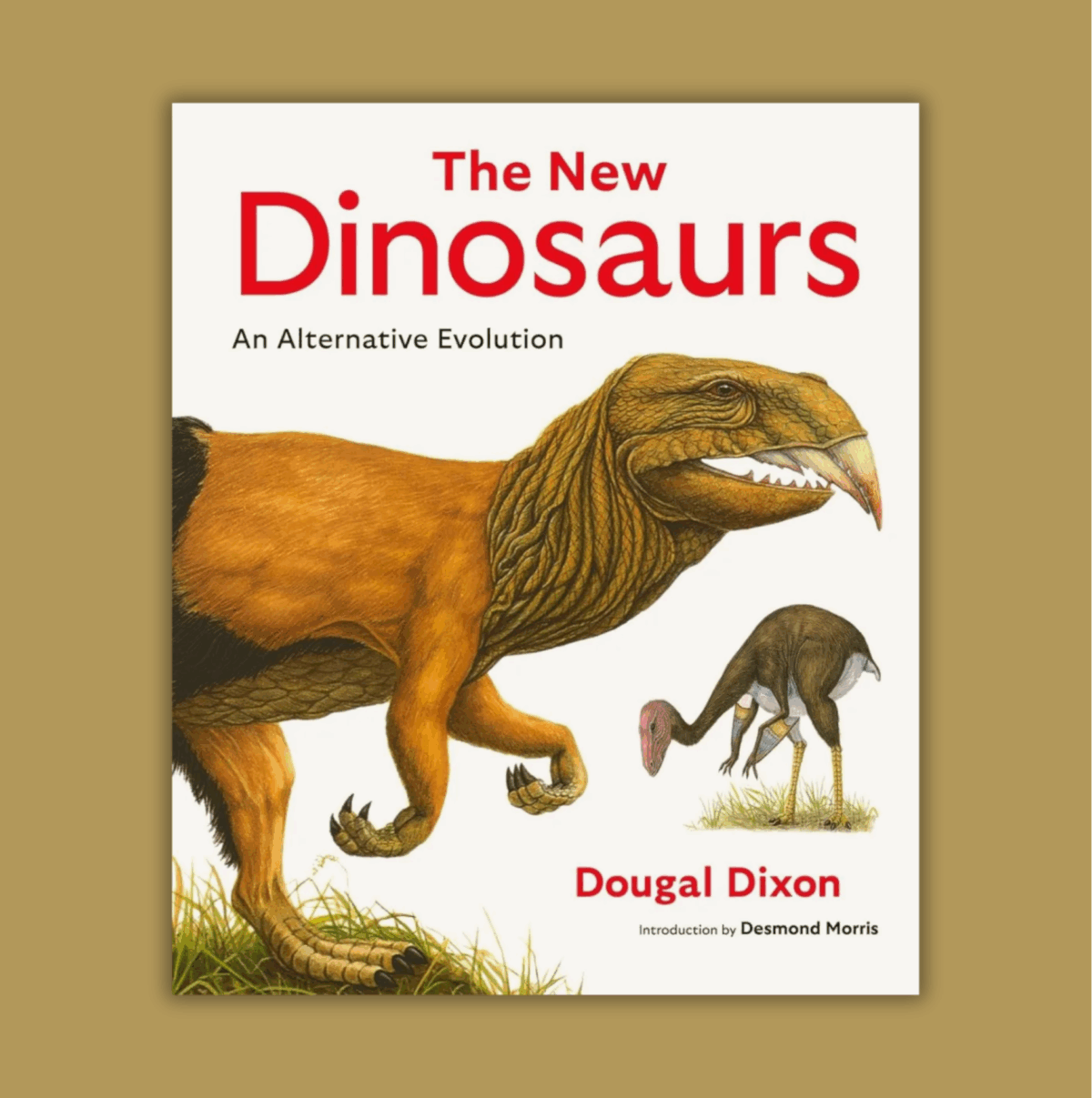

***** Still as captivating and entertaining as in 1988

***** Still as captivating and entertaining as in 1988

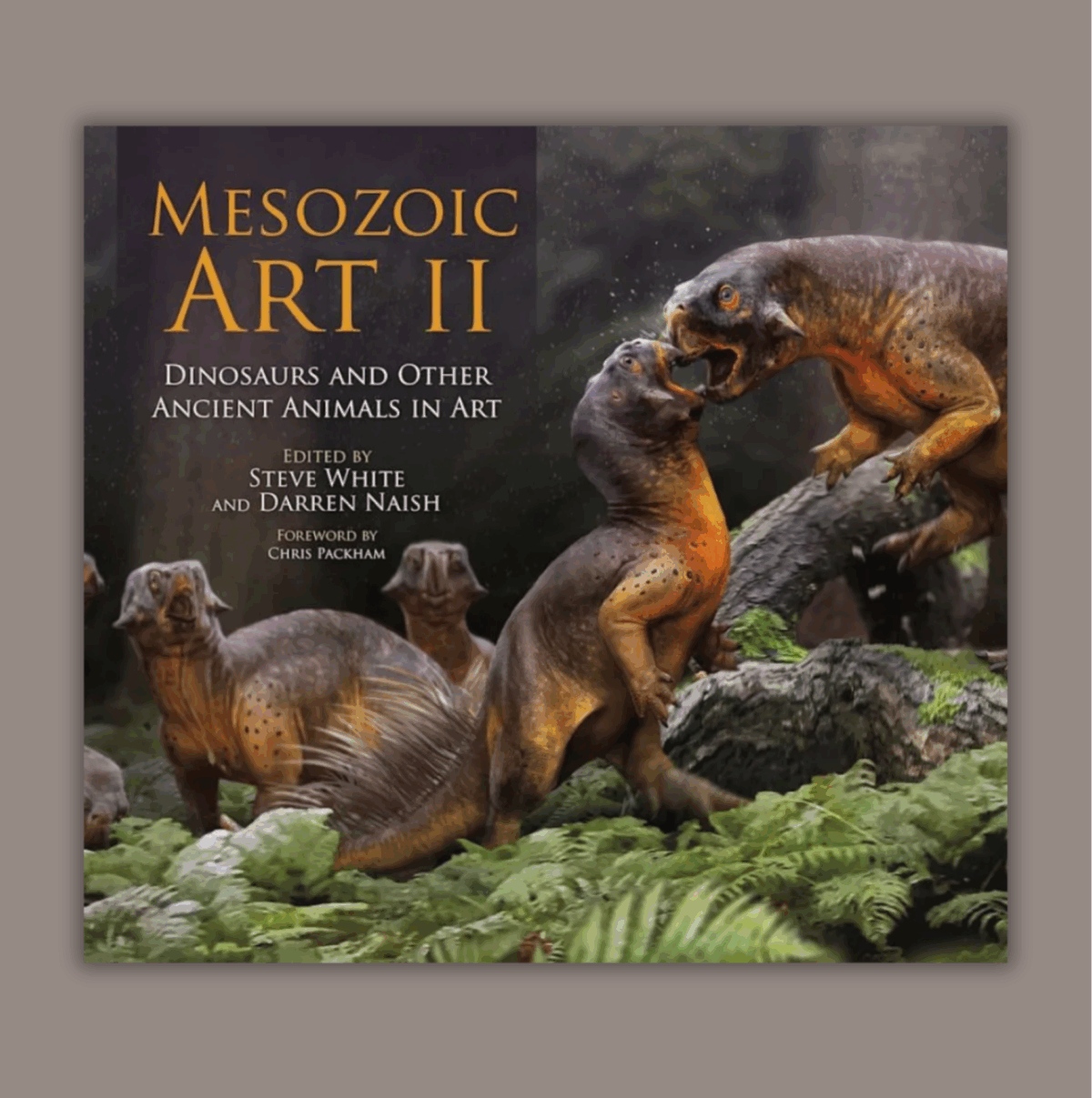

***** A remarkably diverse collection of the very best of current palaeoart

***** A remarkably diverse collection of the very best of current palaeoart

NHBS is delighted to be working with Waterhaul, a company turning harmful marine debris into valuable resources. Their commitment to tackling ocean plastic and promoting sustainable practices aligns closely with our own mission to protect wildlife and the natural environment.

NHBS is delighted to be working with Waterhaul, a company turning harmful marine debris into valuable resources. Their commitment to tackling ocean plastic and promoting sustainable practices aligns closely with our own mission to protect wildlife and the natural environment.