NHBS colleague Dan took a refreshing break from the office to volunteer with the Dartmoor Preservation Association. – Read below to find out what he got up to and what he learned.

Page 357 of Dartmoor 365, a unique compendium of Dartmoor by John Hayward, evokes a tranquil scene of early human settlement amidst the wild moorland that is now High House Waste – a place where remnants of a Bronze Age settlement, including a farmstead and field systems, still endure to this day.

Wedged between two streams, High House Waste’s ecological value is as fascinating as its archaeology.

The northern area consists of dry grass and heathland on granite, while the southern slopes feature wet mires on metamorphosed slate. One can find species such as white beak-sedge, bell heather, bilberry, cotton grass, bog asphodel, and sphagnum mosses. The fauna includes meadow pipits, Dartford warblers, common lizards, field voles, weasels, and various flutter-bys.

You may now better understand why an employee of NHBS would eagerly spend a volunteering day with the Dartmoor Preservation Association (DPA) at such a remarkable site.

This would be my second date with the DPA, an organisation I knew would lead me to a special place.

Led by DPA’s chief executive, Tom Usher, the day’s work party embarked on a grafting session to clear gorse from the ancient remains. High House Waste lies a substantial walk from the nearest parking spot along a farm track. Its remoteness aids preservation from visitor pressure and adds to its sense of moorland wilderness.

Though the gorse may offer some resistance with its prickles, it is a joy to work on the moor in the company of beard-lichen-draped trees and with expansive views stretching across the moor.

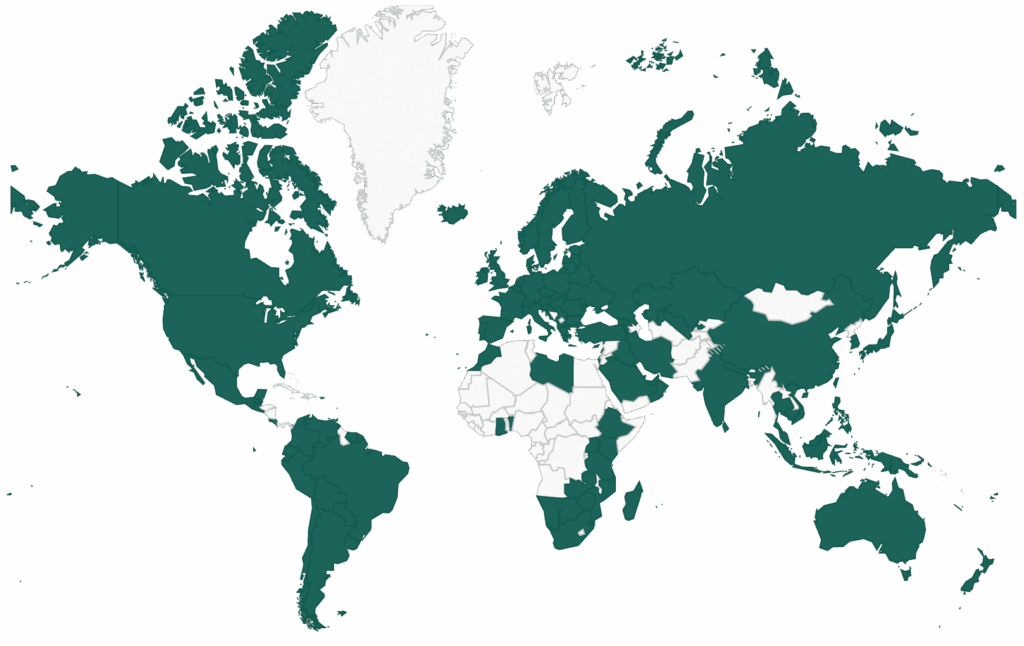

Left unchecked, gorse would quickly take over and obscure the site’s historical treasures. Included in our work party was an ecologist, as DPA regularly engages such experts to monitor the species residing on its grounds. DPA owns four sites on Dartmoor, all purposefully purchased to protect them from threats like industrial development or to impose conditions more respectful of the land’s ecological, historical, and cultural values.

Defending the natural beauty and cultural heritage of Dartmoor has been the DPA’s mission since 1883. Their website details a timeline of actions, testifying to their ongoing work in planning vigilance, access support, surveys, land management, and conservation both on DPA land and beyond.

As the day’s work drew to a close, the quiet moorland around High House Waste stood testament to the delicate balance between nature and history. Through the careful stewardship of organisations like the Dartmoor Preservation Association, these ancient sites continue to breathe life into our understanding of the past while safeguarding the moor’s wild beauty for generations to come.

Volunteering here is more than clearing gorse – it’s participation in guardianship, a chance to connect with the land’s stories and to contribute to a living legacy. In the vastness of Dartmoor’s wilderness, one finds not only remnants of Bronze Age lives but also a call to cherish and protect the natural and cultural treasures that define this remarkable landscape.

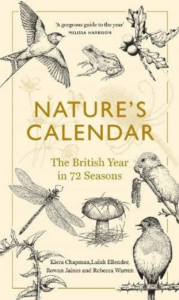

Inspiring reads:

Rock Idols: A Guide to Dartmoor in 28 Tors

A journey through Dartmoor’s ancient tors—where geology, legend, and wild beauty converge to inspire awe and adventure.

Dartmoor

Complete your New Naturalist collection with HarperCollins’ facsimile: Dartmoor—England’s loneliest wilderness, a timeless wildscape of history, mystery, and natural wonder.

OS Explorer Map OL28: Dartmoor

The essential, most detailed companion for every explorer of Dartmoor.