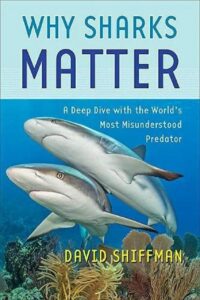

Sharks are some of the most fascinating, most ecologically important, most threatened, and most misunderstood animals on Earth. In Why Sharks Matter: A Deep Dive with the World’s Most Misunderstood Predator, marine conservation biologist Dr David Shiffman explains why it’s crucial that we overcome our misconceptions and rise above cinematic jump scares to embrace sharks as the critically important species that they are.

Sharks are some of the most fascinating, most ecologically important, most threatened, and most misunderstood animals on Earth. In Why Sharks Matter: A Deep Dive with the World’s Most Misunderstood Predator, marine conservation biologist Dr David Shiffman explains why it’s crucial that we overcome our misconceptions and rise above cinematic jump scares to embrace sharks as the critically important species that they are.

Exploring the core tenets of shark conservation science and policy, Shiffman synthesises decades of scientific research and policymaking, weaving it into a narrative full of humour and adventure. Approachable and informative, Why Sharks Matter is perfect for shark enthusiasts, explaining why sharks are in trouble, why we should care and how we can save them.

Dr David Shiffman recently discussed his new book with us, explaining how he became fascinated with sharks, what is being done to change public opinion and why social science research is so important to shark conservation.

Firstly, could you tell us how you became fascinated with sharks and the inspiration behind this book?

I’ve loved sharks for as long as my family can remember, there are pictures of me when I was barely old enough to walk with shark t-shirts and shark toys. I think most kids go through a shark thing or a dinosaur thing, and I never grew out of mine. When I give public talks, inevitably someone will come up to me afterwards and say “I wanted to be a marine biologist when I was a kid”- and I always reply “Me too!”.

In my experience speaking to the public, I’ve realized that lots of people want to help sharks, but don’t necessarily know the most effective ways to do that. And while there are lots of shark books out there, there was nothing that comprehensively lays out the case for having healthy shark populations off our coasts, systematically reviews the different threats to shark species, and thoroughly reviews the different ways that scientists, environmentalists, and the public can help sharks. In short, I wrote the book that I always wished existed, because I know there’s a need for it.

The book does an impressive job of debunking the public image of sharks as dangerous and violent predators. Outside of your own work, what is, if anything, being done to change public opinion about sharks?

As a marine conservation biologist who studies sharks and how to protect them, I know that we need the public to not only no longer fear sharks, but to value the role they play in the ecosystem and to want them around. And I also know that it matters what people do to help, and that there are lots of things that people do while trying to help that are not really helping. I use this book as a chance to bust some myths not only about sharks as mindless killing machines, but also myths about threats to sharks and solutions to these conservation challenges. The subtitle doesn’t call them “the world’s most misunderstood predator” for nothing! In the book, I introduce readers to some of my favourite environmental non-profits who are working to educate the public and persuade policymakers that we need new and stronger laws. If you’re looking for good groups to support, I am happy to recommend them to you.

What do you think is the biggest threat to sharks and what can the average person do to help?

The science is clear on this point: the biggest threat to sharks is unsustainable overfishing, including but not limited to the shark fin trade (which many well-intentioned shark-o-philes wrongly believe is that only threat to sharks). The single most effective thing that an individual consumer can do to help not only sharks but the whole ocean is to not eat unsustainable seafood. Notice that I did not say “give up all seafood and become vegan,” because while that’s a perfectly valid personal choice, the people claiming that we all need to do this or the oceans are doomed are not telling the truth. If you, like me, love seafood, just choose to buy sustainable seafood.

You share a range of scientific tools used to monitor sharks, from eDNA to telemetry tracking, but you also highlight the importance of social science research. Why do you think this approach is important to shark conservation?

A major goal of the conservation movement is passing new laws or regulations to protect endangered species, but notably these laws do not limit what the animals can do, they only control humans. Therefore, we need to understand what humans want, what humans do, and what humans know–and these are questions that the social sciences are designed to answer.

What is your vision for the future of shark conservation? Are you hopeful or pessimistic?

I am cautiously optimistic about the future of the ocean. More people care and want to help than ever before, and if we can channel that energy into something productive, we can move mountains!

And lastly, do you have any current projects or plans for the future that you would like to tell us about?

I’m always on the move, always up to some new project. If anyone would like to follow my adventures, or to ask me anything you want to know about sharks, I invite you to follow me on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @WhySharksMatter.

Why Sharks Matter: A Deep Dive with the World’s Most Misunderstood Predator

Why Sharks Matter: A Deep Dive with the World’s Most Misunderstood Predator

By: Dr David Shiffman

Hardback | May 2022 | £18.50

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

I was originally studying how birds might choose their mates on the basis of certain immune genes, following the idea that animals could prefer mates with different genes than their own, leading to offspring with stronger immune systems. I was struggling to sequence these genes, and I complained to a colleague who happened to be studying bird brains. He said, “I don’t know why you’d study that in birds – information about those genes is sensed by smell, and birds don’t have much of a sense of smell.” I had never heard that before, and the idea that a whole group of animals would lack such an important sense seemed absurd to me. So, I started investigating.

I was originally studying how birds might choose their mates on the basis of certain immune genes, following the idea that animals could prefer mates with different genes than their own, leading to offspring with stronger immune systems. I was struggling to sequence these genes, and I complained to a colleague who happened to be studying bird brains. He said, “I don’t know why you’d study that in birds – information about those genes is sensed by smell, and birds don’t have much of a sense of smell.” I had never heard that before, and the idea that a whole group of animals would lack such an important sense seemed absurd to me. So, I started investigating.