The next habitat in our NHBS Introduction to Habitats series is farmland. Farmland encompasses a wide variety of different habitats, many of which can be rich in wildlife. Farmland itself is not defined under the UK Biodiversity Action Plan as a habitat, but it contains four habitat types that are identified: arable and horticulture, boundary and linear features, improved grassland and standing open water. These habitats are important for many plant species, as well as a variety of birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles.

Farming has been a part of the UK landscape for thousands of years and methods are constantly changing as consumer tastes shift and new technological innovations emerge. With an estimated three-quarters of the UK being farmland, it is unsurprising that these habitats are used by so many species. It is also not surprising just how important environmentally friendly farming practices are.

The need to utilise as much of the land as possible to increase productivity has led to a rapid decline of boundary and linear features, such as stone walls and hedgerows. These features constitute a significant ecological part of the farmland habitat, providing variety, food and shelter for wildlife, as well as helping to reduce run-off, flooding and soil erosion. Hedgerows and tree lines can also play an important role in carbon sequestration in agricultural landscapes.

What species can you find here?

Flora

Beyond crop species, farmland can be home to a large number of flora species that can all play key roles in the ecosystem. These plants support the large variety of fauna species found on farmland. The abundance and diversity of plant species depends on the type of habitat and the level of ‘improvement’. Improved grasslands are areas that have been re-seeded and treated with chemicals, such as fertilisers, herbicides and pesticides, and typically species diversity is much lower compared to unimproved or semi-improved grasslands.

Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa)

A common hedgerow species, blackthorn flowers in early spring and produces fruits in autumn and winter, providing an important food source for many species, including invertebrates and birds. It is visually similar to several other species, such as wild plum and wild cherry, but can be distinguished by its fruit size, leaf shape and the time of year that the flowers bloom.

Common Hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna)

Hawthorn is another common hedgerow species, providing food and shelter for species such as yellowhammers (Emberiza citrinella) and the hawthorn moth (Scythropia crataegella). The red berries, called haws, develop during autumn and winter, and are an important source of food during the colder months for many farmland species. Did you know that hawthorn was originally associated with May Day? It was used before the development of the Maypole, with its leaves and flowers used in garlands.

White Clover (Trifolium repens)

This plant is often used as a companion plant for crops, providing additional ground cover to reduce soil erosion. White clover also fixes nitrogen within the soil, allowing for better crop growth. Clover suppresses the growth of unwanted or damaging plants too, and also acts as a trap for pests to draw them away from valuable crop plants. This practice helps to improve farmland for wildlife as it prevents it from becoming a monoculture, adding more variety in food and shelter resources. The use of cover crops within agriculture has reduced, however, and white clover is much less abundant on farmland than it once was.

Creeping Thistle (Cirsium arvense)

The creeping thistle is an important source of food for many farmland birds, such as goldfinches and linnets, but it’s often considered a ‘weed’ and is normally quite heavily managed on agricultural land. Its flower heads consist of lilac-pink florets on a cylinder of spiny leaf-like structures called bracts. During the late summer, it releases fluffy, wind-borne seeds en masse.

Fauna

Many iconic UK species use farmland and the fauna present changes depending on the time of year. Farmland can seem to come alive during spring and summer, although there is still much to see during the colder months.

Grey Partridge (Perdix perdix)

This species is an iconic part of farmland wildlife, with its orange face, dark black semi-circle patch on its abdomen and stripy grey and orange-brown feathers. The grey partridge relies on the seeds, leaves and certain invertebrate species that it finds in open farmland and has a preference for areas with hedges. It is a ground-nesting bird, laying the most number of eggs per clutch of any bird (the record is 25).

Grey partridge numbers have declined by more than 80% in the UK since the 1980s. This has mostly been attributed to a loss of seed sources, habitat loss and predation, for example by cats and foxes. Luckily there are several conservation efforts in place to help this species.

Yellowhammer (Emberiza citrinella)

These brightly coloured birds prefer open countryside with bushes and hedgerows, and so they are often found in farmland habitats. Yellowhammers feed on invertebrates and seeds, relying on farmland seeds during the winter as snow cover can make it difficult to find food elsewhere.

Heart and Dart Moth (Agrotis exclamationis)

Farmland habitats are home to a great many invertebrate species, with a large variety of butterflies and moths. The heart and dart is an easily identifiable moth due to its distinctive markings. It has a blackish v-shaped collar, with a dark dart mark and two circular marks on its wings. The wing colour can vary from lightish grey to a much darker brown. They feed on a variety of plants such as brambles (Rubus spp.), maize (Zea spp.) and lettuce (Lactuca spp.).

Brown Hare (Lepus europaeus)

While not a true native to the UK, as they were thought to have been introduced during Roman times, this species is now considered naturalised. It prefers a mixture of grassland, arable fields and hedgerows, grazing on vegetation and the bark of young, woody plants. Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) can also be seen on farmland, although they can be distinguished quite easily as hares are much larger, with longer limbs and longer, black-tipped ears.

Farmland can also support many of the UK’s small mammal species. For more information on those, check out our NHBS Guide to UK Small Mammal Identification.

Threats

Intensification of agricultural practices has led to a reduction in habitat areas that are seen as unproductive, such as hedgerows, rough grassland and open water areas. It has been reported that 60% of farmland species are now in decline. As well as agricultural intensification, other factors behind this decline include changes in farming practices; the use of harmful chemicals, such as insecticides; overgrazing by livestock; destruction of habitats and soil erosion.

Habitat changes caused by development, afforestation or conservation efforts that prioritise alternative habitat types can also pose a threat to farmland. As can changes in management, or a lack thereof; the abandonment of farmland can lead to encroachment by scrubs and trees. While scrubland can be an important habitat for many wildlife species, it is not necessarily suitable for all farmland species, such as ground-nesting birds that prefer open habitats. This could lead to a change in community structure and may even lead to localised extinction of vulnerable species that rely on farmland and cannot survive in other habitats. Changes in land use through development can also impact in a similar way. Furthermore, if the land was originally woodland or wetland, for example, there may be a push to restore it to its previous habitat type, which may not be suitable for the species previously inhabiting the farmland area.

Farmland habitats also face climate change-related challenges. Changes in precipitation, increased extreme weather and increased temperatures can lead to soil degradation, reduced plant growth and changes in the availability of food, shelter and fresh water for wildlife. These factors can also impact crop production, and where this results in reduced yields, this increases the need for agricultural intensification to meet demands, further impacting the farmland ecosystem.

Hopes for the future

A change in the way farmers receive subsidies may signal a shift away from a rather bleak picture for these habitats. Previously, farmers were paid grants based on how much land they owned and farmed. This encouraged them to use as much of their land for productivity as possible. Now, however, farmers will be paid for more sustainable practices instead. Under the Sustainable Farming Incentive, grants will be rewarded for restoration of non-crop habitats, the provision of resources for farmland species year-round and reducing the use of harmful pesticides.

Useful resources and further reading

Farming and Birds

Farming and Birds

Ian Newton

Hardback | £32.50 £34.99

Farmland Conservation: Evidence for the effects of interventions in northern and western Europe

Farmland Conservation: Evidence for the effects of interventions in northern and western Europe

Lynn V Dicks et al

Paperback | £34.99

The Shepherd’s Life: A Tale of the Lake District

James Rebanks

Paperback | £9.99

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

For nearly thirty years now I have been going to stay in a small house at the head of a bay on the west coast of Scotland. It is somewhere my wife’s family have been going for generations and now our children and grandchildren love it too. It has everything you might long for from a place like that: cliffs, woods, waterfalls, a dark beach made of basalt sands, a lighthouse, a ruined castle, stories, beauty, birds, fish; but one thing it did not have because of the geology, was a rockpool. For years I have dreamed of making one – a place of stillness set in the tide, and this book is the story of how I made three of them in different parts of the bay; one dug in with a pickaxe; one made by damming a narrow exit to the sea from a hollow so that the dam held the pool behind it; and one by making a circular wall low down in the intertidal.

For nearly thirty years now I have been going to stay in a small house at the head of a bay on the west coast of Scotland. It is somewhere my wife’s family have been going for generations and now our children and grandchildren love it too. It has everything you might long for from a place like that: cliffs, woods, waterfalls, a dark beach made of basalt sands, a lighthouse, a ruined castle, stories, beauty, birds, fish; but one thing it did not have because of the geology, was a rockpool. For years I have dreamed of making one – a place of stillness set in the tide, and this book is the story of how I made three of them in different parts of the bay; one dug in with a pickaxe; one made by damming a narrow exit to the sea from a hollow so that the dam held the pool behind it; and one by making a circular wall low down in the intertidal.

And so that provided the model – see what was there and look carefully at it. Of course, books like mine are entirely parasitic on the work of many generations of biologists and that too turned out to be the pattern. Watch the sand hoppers and then read about them. Read about them and see how much of what I read I could find on the shore. With prawns, winkles, shore crabs, anemones, limpets, sea-stars, urchins and barnacles, I simply oscillated between the pools and my books: what was there? What had people discovered about them? How did they interact? What were the principles governing their presence or absence? And with all of that came the repeated and slightly sobering realisation that unless I knew to look for something it was very difficult to see it was there. Mysteriously, we are often blind to what is in front of our eyes.

And so that provided the model – see what was there and look carefully at it. Of course, books like mine are entirely parasitic on the work of many generations of biologists and that too turned out to be the pattern. Watch the sand hoppers and then read about them. Read about them and see how much of what I read I could find on the shore. With prawns, winkles, shore crabs, anemones, limpets, sea-stars, urchins and barnacles, I simply oscillated between the pools and my books: what was there? What had people discovered about them? How did they interact? What were the principles governing their presence or absence? And with all of that came the repeated and slightly sobering realisation that unless I knew to look for something it was very difficult to see it was there. Mysteriously, we are often blind to what is in front of our eyes. stages, can recognise the movements and timings of the tides. That sea anemones can identify other sea anemones that are not their relations and effectively destroy them. That prawns have an imagination – that might sound like too much, but it has been shown that they can remember past pain and project it into present and future anxieties. Anxiety is different from fear; it is a fear of what might be there. In other words a prawn can think beyond its present reality.

stages, can recognise the movements and timings of the tides. That sea anemones can identify other sea anemones that are not their relations and effectively destroy them. That prawns have an imagination – that might sound like too much, but it has been shown that they can remember past pain and project it into present and future anxieties. Anxiety is different from fear; it is a fear of what might be there. In other words a prawn can think beyond its present reality. garden whose walls are dissolved twice a day, an enclosure that becomes part of the general world with every high tide. That ambiguity is what entranced me, the sense of its being a micro-ocean, a micro-arcadia, a micro-laboratory in which all kinds of intimacies and precision in natural beings can be witnessed an inch beneath your nose.

garden whose walls are dissolved twice a day, an enclosure that becomes part of the general world with every high tide. That ambiguity is what entranced me, the sense of its being a micro-ocean, a micro-arcadia, a micro-laboratory in which all kinds of intimacies and precision in natural beings can be witnessed an inch beneath your nose.

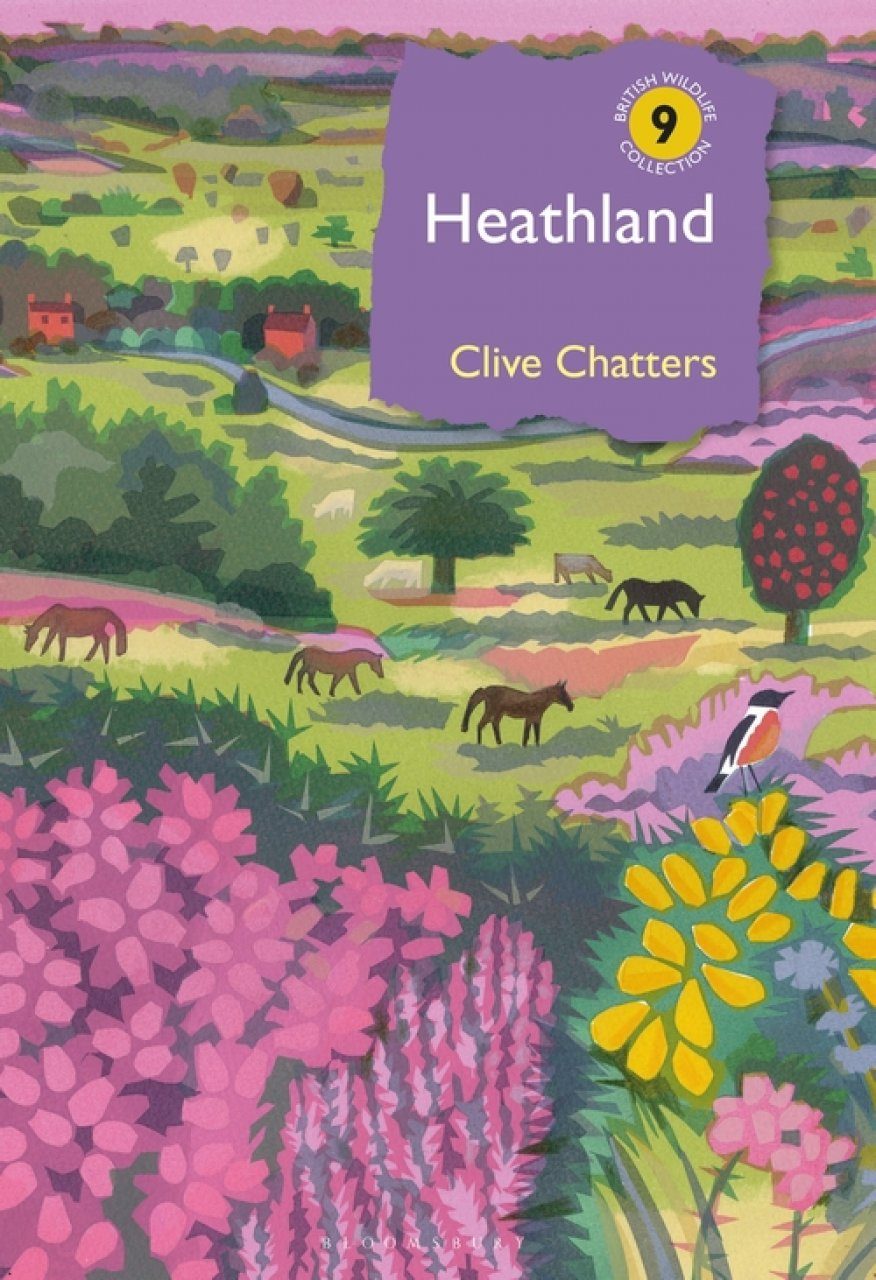

Heathlands defy ready definition. The diverse places that we call heaths are cultural landscapes which are overlain with the language of ecology. It is unnecessary to reconcile these different perspectives as both traditions offer a path to understanding what makes our heathlands special.

Heathlands defy ready definition. The diverse places that we call heaths are cultural landscapes which are overlain with the language of ecology. It is unnecessary to reconcile these different perspectives as both traditions offer a path to understanding what makes our heathlands special. It is not inevitable that the catastrophic losses of the recent past are the destiny of our remaining heaths. Whilst there are still significant challenges to overcome, we know enough about these habitats to secure their place in the countryside of the future, as an integral part of British culture and home to a wealth of species that occupy ecosystems of immense richness.

It is not inevitable that the catastrophic losses of the recent past are the destiny of our remaining heaths. Whilst there are still significant challenges to overcome, we know enough about these habitats to secure their place in the countryside of the future, as an integral part of British culture and home to a wealth of species that occupy ecosystems of immense richness. Heathlands are a great deal more than just carpets of heathers. A heathland landscape can embrace habitats as diverse as rocks and lakes and bogs, even temporary stands of arable and wartime concrete. The component habitats of a large functioning heathland are naturally dynamic, with species dependant on all sorts of habitat formations, from bare ground to the decaying of cowpats. The great antiquity of heathland ecosystems is reflected in the network of interdependent species, many of which are associated with large herbivores, fire and occasional gross disturbance of the soil. Whilst charismatic birds and reptiles have traditionally claimed the limelight, the biological wealth of the heath is better expressed through its invertebrates, lichen and wildflowers.

Heathlands are a great deal more than just carpets of heathers. A heathland landscape can embrace habitats as diverse as rocks and lakes and bogs, even temporary stands of arable and wartime concrete. The component habitats of a large functioning heathland are naturally dynamic, with species dependant on all sorts of habitat formations, from bare ground to the decaying of cowpats. The great antiquity of heathland ecosystems is reflected in the network of interdependent species, many of which are associated with large herbivores, fire and occasional gross disturbance of the soil. Whilst charismatic birds and reptiles have traditionally claimed the limelight, the biological wealth of the heath is better expressed through its invertebrates, lichen and wildflowers.

While you’re in the garden cleaning your nest boxes, why not take the opportunity to clean out your feeders and bird table too, ready for use over the winter. To thoroughly clean a bird feeder, first empty out all of the old food. Mix up a solution of animal-safe disinfectant in a bucket and soak the feeders for 10-15 minutes. Use a

While you’re in the garden cleaning your nest boxes, why not take the opportunity to clean out your feeders and bird table too, ready for use over the winter. To thoroughly clean a bird feeder, first empty out all of the old food. Mix up a solution of animal-safe disinfectant in a bucket and soak the feeders for 10-15 minutes. Use a