Shieldbugs are insects in the superfamily Pentatomoidea. They are characterised by their well-developed scutellum, the hardened extension of the thorax over the abdomen. Many shieldbug species are triangular, with a broad pronotum and pointed end to the abdomen. They also produce a foul-smelling liquid from their prothoracic glands, which inspired the American name “stink bug”, although this name is specific to the family Pentatomidae.

Some shieldbugs are considered pest species due to the damage they can cause to crops. The recent arrival of the brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys) to the UK is considered a serious threat to fruit and vegetable crops. They damage the salability of produce and can even contaminate the taste of juice or wine, causing waste and a loss in income.

Identifying shieldbugs is usually based on structural characteristics, body length (from the head to the end of the abdomen, ignoring the antennae and legs), and species range. Colouration and pattern can be useful but there is often variation between individuals of the same species. Using a hand lens, sweep net or beating tray can help when surveying for shieldbugs. A field guide that includes juvenile stages would also be useful as nymphs can often have different colour patterns to adults.

Hawthorn Shieldbug (Acanthosoma haemorrhoidale)

Distribution: Widespread across the UK.

What to look for: The most common shield bug in the UK, the hawthorn shieldbug is also UK’s largest. Its scutellum and pronotum are green, framed with red sides. The ‘shoulders’ of its pronotum are pointed with red and black tips, and its corium, the thickened basal portion of the forewing, is red. Its wing membrane can vary in colour but is usually red.

Similar species: The birch shieldbug (Elasmostethus interstinctus) but this species does not have a green scutellum. The juniper shieldbug (Cyphostethus tristriatus) is also similar but this species does not have a red wing membrane.

Common Green Shieldbug (Palomena prasina)

Distribution: Widespread in England, Wales, and parts of Northern Ireland.

What to look for: This is a larger species, with a dark wing membrane and a bright green body during summer. The adults become a bronze-brown colour in the autumn before hibernating throughout winter.

Similar species: The southern green shieldbug (Nezara viridula), a non-native species. However, this species has paler wings than the common green shieldbug.

Parent Bug (Elasmucha grisea)

Distribution: Occurs across the UK but most commonly in south-east and central England.

What to look for: This is a medium-sized species with red and beige colouration. Most individuals have a black patch on the scutellum. This species also has a black and white connexivum, the flattened lateral border of the abdomen.

Pied Shieldbug (Tritomegas bicolor)

Distribution: Widespread across the south-east and central England.

What to look for: This species does not have the characteristic triangular shape and could be confused for a ladybird. It has a black and white piebald pattern, with a grey or translucent wing membrane. Its pronotum is black with a white spot on each ‘shoulder’.

Similar species: Rambur’s pied shieldbug (Tritomegas sexmaculatus), although this species has a black wing membrane.

Juniper Shieldbug (Cyphostethus tristriatus)

Distribution: Common in southern and central England, with an expanding range.

What to look for: This is a bright green species, with a green pronotum, head and scutellum. They have pinkish-red markings on their corium. Their wing membrane is green with a black X-shaped mark.

Similar species: The birch and hawthorn shield bugs are visually similar but neither species has the black X-shaped mark on their wing membrane.

Striped Shieldbug (Graphosoma italicum)

Distribution: First recorded in the UK in 2020, only found in two sites in London.

What to look for: Also known as the Italian striped bug and the minstrel bug, their body is rounded with bold red and black longitudinal stripes. Their connexium is black with several black, square-shaped spots.

Similar species: There are several similar species, such as Graphosoma lineatum, but none are found in the UK.

Ornate Shieldbug (Eurydema ornata)

Distribution: Coastal areas between Devon and Sussex, scattered in other parts of southern England.

What to look for: They have a distinctive red and black pattern across their pronotum and abdomen. There are other colour morphs, however, and they can have a white and yellow background with the same black markings. They have a black head with a red, white or yellow ‘mouth’ shape and a black wing membrane.

Similar species: The scarlet shieldbug (Eurydema dominulus). They can be distinguished by the pattern on their corium. The ornate shieldbug has a thin black line, two spots and a washed-out area, compared to the thicker line, one or no spots and no washed-out area on the scarlet shieldbug.

Blue Shieldbug (Zicrona caerulea)

Distribution: Widespread across Britain, particularly in the north, and absent from Ireland.

What to look for: The blue shieldbug has a deep blue-green metallic sheen, with a dark wing membrane. They resemble leaf beetles, species in the Altica genus, whose larvae they predate upon. This is called aggressive mimicry, where a predator resembles its prey to avoid detection.

Bishop’s Mitre Shieldbug (Aelia acuminata)

Distribution: Widespread across southern Britain.

What to look for: This is a straw-coloured species, with brown longitudinal stripes, a distinctive pointed head and a ridged pronotum.

Similar species: Mecidea lindbergi is another elongated shield bug but it is a thinner species without brown stripes.

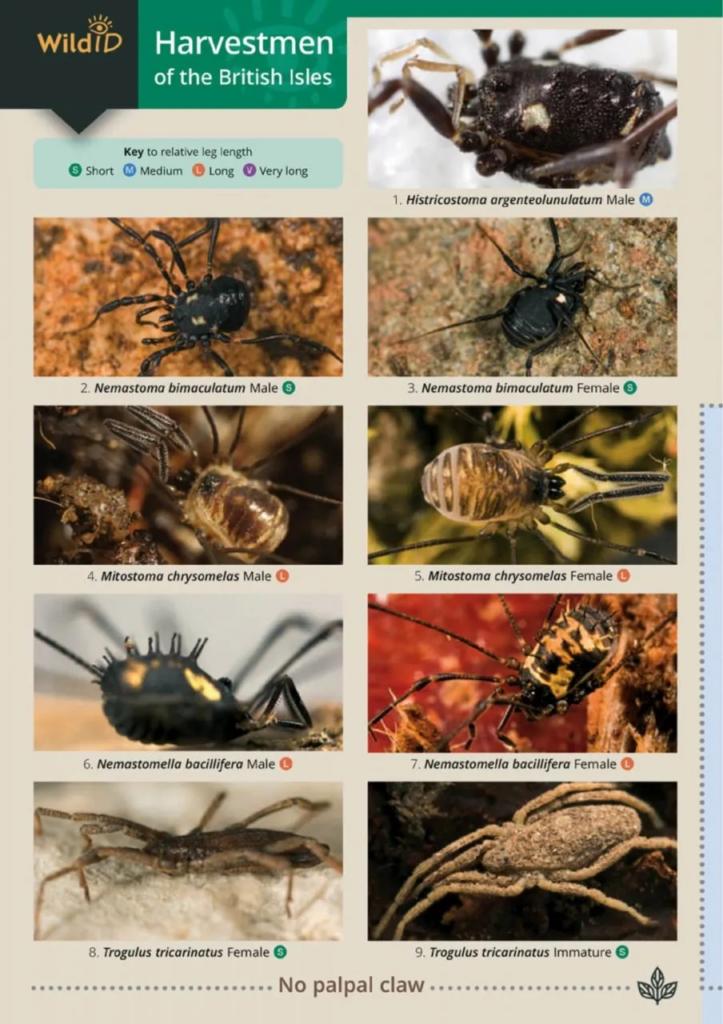

Suggested reading and equipment:

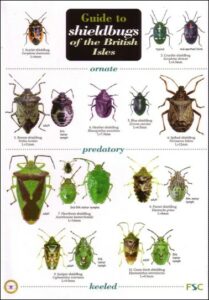

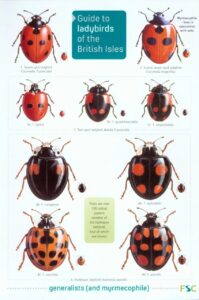

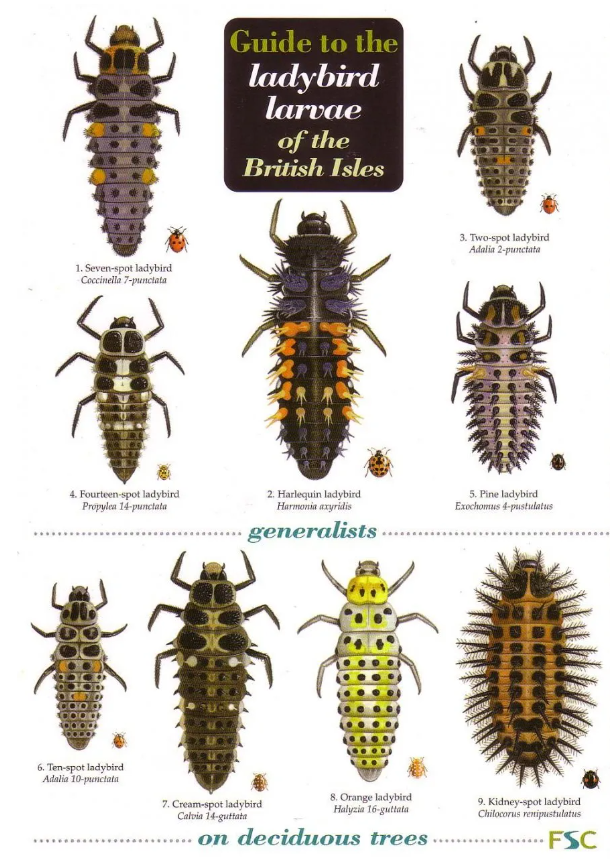

Guide to Shieldbugs of the British Isles

Guide to Shieldbugs of the British Isles

£3.75

A Pocket Guide to the Shieldbugs and Leatherbugs of Britain and Ireland

A Pocket Guide to the Shieldbugs and Leatherbugs of Britain and Ireland

£12.99

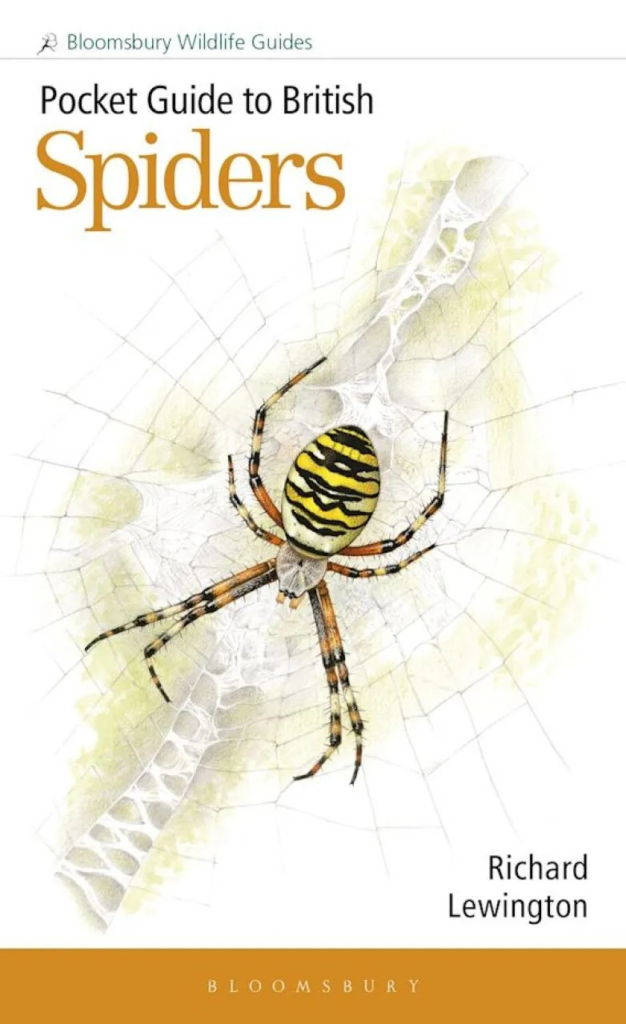

£29.95

£49.96

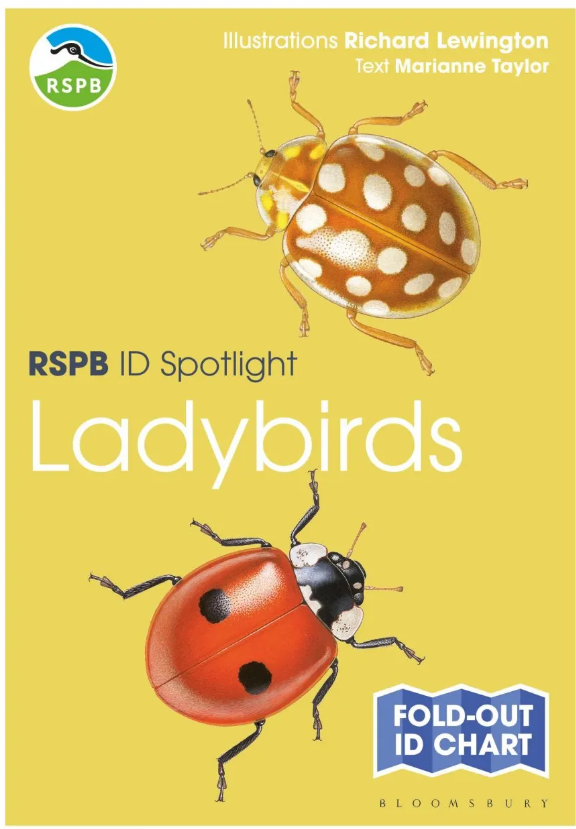

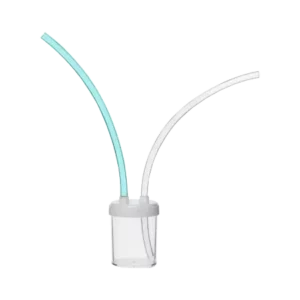

£3.95

From £0.35

Opticron Hand Lens 23mm 15x Magnification

Opticron Hand Lens 23mm 15x Magnification

£14.50 £16.50

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

RHS The Little Book of Wild Gardening

RHS The Little Book of Wild Gardening Gardening for Bumblebees

Gardening for Bumblebees

Recently added to our range, the

Recently added to our range, the

natural world and to human society. With an expert eye, Goulson skillfully guides the reader through different aspects of their importance, from the multi-million pound service that dung beetles provide the farming industry each year in the UK alone to the vital role that pollinators play in underpinning ecosystems across the planet, and the value that insects have in their own right as beautiful, vibrant denizens of our planet. The author’s passion is infectious; it is difficult to read this section without becoming invested in the wondrous ranks of the planet’s invertebrates, making the threat of their decline feel all the more personal.

natural world and to human society. With an expert eye, Goulson skillfully guides the reader through different aspects of their importance, from the multi-million pound service that dung beetles provide the farming industry each year in the UK alone to the vital role that pollinators play in underpinning ecosystems across the planet, and the value that insects have in their own right as beautiful, vibrant denizens of our planet. The author’s passion is infectious; it is difficult to read this section without becoming invested in the wondrous ranks of the planet’s invertebrates, making the threat of their decline feel all the more personal.  controversial among some parties. He consistently highlights the arguments of his critics, treating them with respect and validation. At some points he provides his rebuttal while at others he admits to the shortcomings of the relevant research, explaining why a different approach was impossible at the time. This is indicative of an attitude that permeates the book – the issues that he writes about are bigger than minor gripes with experimental methodologies, bigger than business margins or political leanings. He presents with a neutral eye the irrefutable reality that insects are vanishing at a terrifying rate, and unless action is taken the world is heading towards a very real disaster within generations. Though frequently distressing and at times heartbreaking, Goulson writes with a voice compelling and just witty enough to prevent the reader from becoming despondent. This book is not intended to drive us to despair, but to action.

controversial among some parties. He consistently highlights the arguments of his critics, treating them with respect and validation. At some points he provides his rebuttal while at others he admits to the shortcomings of the relevant research, explaining why a different approach was impossible at the time. This is indicative of an attitude that permeates the book – the issues that he writes about are bigger than minor gripes with experimental methodologies, bigger than business margins or political leanings. He presents with a neutral eye the irrefutable reality that insects are vanishing at a terrifying rate, and unless action is taken the world is heading towards a very real disaster within generations. Though frequently distressing and at times heartbreaking, Goulson writes with a voice compelling and just witty enough to prevent the reader from becoming despondent. This book is not intended to drive us to despair, but to action.  encouraging native plants in our towns and cities and overhauling the way in which we view farming. Finally, there is an extensive list of actions, large and small, that people can take, listed by occupation. This section is what the book has been building to, and it is worth reading for this alone. As usual, respect is paid to all viewpoints and all members of society. It doesn’t matter whether the reader is in a position where a free-range organic, locally sourced diet is financially viable or not – there will be other actions that they can take regardless of financial matters. Nor does it matter if they have beliefs, political or economic, that might conflict with the author’s. It is a call for society to overlook such matters which are, in the face of such a crisis, trivial.

encouraging native plants in our towns and cities and overhauling the way in which we view farming. Finally, there is an extensive list of actions, large and small, that people can take, listed by occupation. This section is what the book has been building to, and it is worth reading for this alone. As usual, respect is paid to all viewpoints and all members of society. It doesn’t matter whether the reader is in a position where a free-range organic, locally sourced diet is financially viable or not – there will be other actions that they can take regardless of financial matters. Nor does it matter if they have beliefs, political or economic, that might conflict with the author’s. It is a call for society to overlook such matters which are, in the face of such a crisis, trivial.