To celebrate International Day of Women and Girls in STEM we chatted with Dr Antje Steinfurth, Conservation Scientist at the RSPB.

Antje has been studying Penguins for over two decades and is the RSPB’s resident expert on these birds. Antje currently focuses on the UK Overseas Territory of Tristan da Cunha, a very remote, volcanic island in the South Atlantic which is a haven for many globally rare animals and plants, including shearwater species and an endemic albatross. Antje’s penguin expertise is helping to protect one of the islands’ most charismatic but threatened species, the Northern Rockhopper.

We had the pleasure of asking Antje a few questions about her extraordinary career and the importance of International Day of Women and Girls in Science.

Can you share a bit about your background and what inspired you to pursue a career in conservation science?

I have always been drawn to nature and wildlife, which led me to study Biology at the University of Göttingen in Germany. Wanting to focus more on marine ecology, I later moved to Kiel University, where I completed my Diploma in Biology and, subsequently, a PhD in Marine Zoology.

Increasing awareness of the threats facing biodiversity motivated me to use science not just to understand wildlife, but to actively help protect it. After albatrosses, penguins are the second most threatened family of seabirds, with currently ten of the 19 species being of global conservation concern. During my Diploma studies, I worked on the foraging behaviour of Magellanic Penguins in Argentina. What I didn’t realise at the time was that penguins would accompany me throughout my professional life – literally leading me from the equator to Antarctica.

Supported by a German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) scholarship, my doctoral research took me to the Galápagos Islands, where I spent two and a half years studying the marine ecology and conservation of the endangered, endemic Galápagos Penguin. After completing my PhD, I was a visiting scientist at the University of Bristol, contributing to an international, interdisciplinary project on African Penguins, another banded species now listed as Critically Endangered.

I then took up a postdoctoral position at the University of Cape Town, working on a range of seabird conservation projects and joining the South African National Antarctic Programme. Through this work, the sub-Antarctic islands became a second home. A project on the endangered Northern Rockhopper Penguins eventually led me to Tristan da Cunha, the world’s most remote inhabited island, which has been my ‘home away from home’ since 2012.

Since 2017, I have been based in Cambridge, UK, working as a scientist at the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) where I continued my work on Northern Rockhopper Penguins and now lead the science and monitoring programme for threatened seabird species on Gough Island.

Science alone cannot save threatened species, but it provides a powerful tool to transform data into practical and hopefully long-lasting conservation outcomes.

What does your current role at the RSPB involve?

I work as a Conservation Scientist with the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) in the UK. My research focuses on the UK Overseas Territory of Tristan da Cunha in the central South Atlantic, where I collaborate closely with local partners and the community to support the sustainable protection and management of globally important habitats and species.

Embedded within the Gough Island Restoration Programme, I lead the long-term science and monitoring programme on Gough Island, supporting efforts to restore one of the world’s most important seabird breeding sites.

I am also, unofficially, RSPB’s ‘penguinologist in residence’. With more than two decades of experience in penguin research, I work closely with the Tristan Conservation Department to help protect one of the islands’ most charismatic yet endangered species, the Northern Rockhopper Penguin.

More broadly, my work aims to improve understanding of the processes that shape species distributions, demography, and population dynamics, in order to inform effective conservation strategies. From 2020 to 2022, I also served as RSPB Project Manager for the UK Seabirds Count, coordinating RSPB’s delivery of this national monitoring programme.

Is there a female role model in the conservation sector who has influenced you, and what makes her inspiring to you?

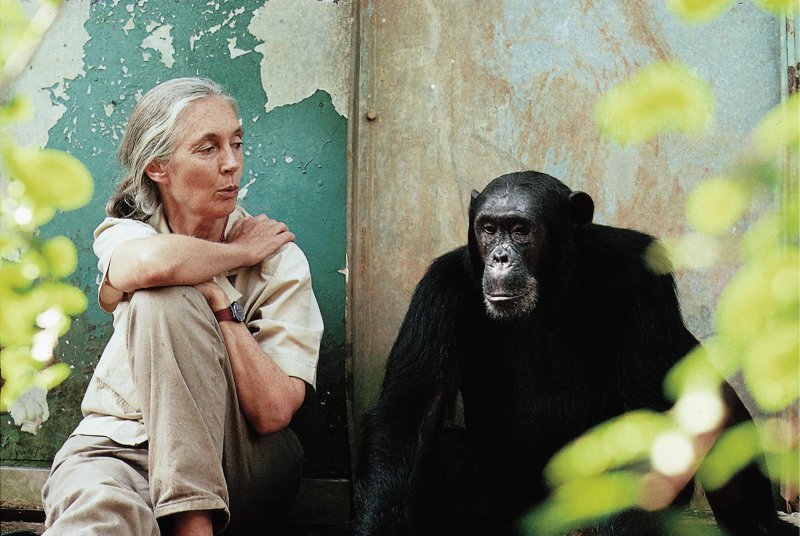

For many women of my generation, figures like Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey have been important role models. They challenged expectations, broke barriers, and pursued their passions with remarkable curiosity, courage and dedication. Their commitment to species and habitat conservation, often in the face of significant obstacles, has been deeply inspiring. Jane Goodall, in particular, has always reminded me that hope is essential, and that believing change is possible is just as important today as it ever was.

Despite progress, gender bias in STEM still exists. I feel fortunate to work in a field that attracts a more balanced mix of genders and to be surrounded by inspiring women and supportive colleagues of all genders. Being part of an organisation with visible female leadership and a genuinely inclusive culture has been crucial in shaping my confidence, career progression, and sense of belonging in STEM.

One woman I especially want to highlight is Juliet Vickery, now CEO of the BTO. When I joined the RSPB, she was Head of the International Section in the Conservation Science Department and later became my line manager. She has been an invaluable mentor and a true inspiration, in both leadership and pursuing a career in conservation science with scientific rigor, care and compassion.

She is a true champion for women in STEM, advocating for equality, supporting career development, and creating opportunities for others to thrive. I am deeply grateful for her guidance, support, and unwavering commitment to fostering an inclusive and empowering environment.

NHBS is excited to be working with Button and Squirt – a company with a strong focus and commitment to environmental education for children. Specialising in creating nature-themed educational games, Button and Squirt has a wide range of unique and engaging fact cards, activity books and other products.

NHBS is excited to be working with Button and Squirt – a company with a strong focus and commitment to environmental education for children. Specialising in creating nature-themed educational games, Button and Squirt has a wide range of unique and engaging fact cards, activity books and other products.

As a self-taught nature illustrator, Ferne Glannan-MacRae brings the intricacies of British species to life using Procreate on iPad. Her designs are inspired by a love for the environment and, in particular, British wildlife.

As a self-taught nature illustrator, Ferne Glannan-MacRae brings the intricacies of British species to life using Procreate on iPad. Her designs are inspired by a love for the environment and, in particular, British wildlife.