Often seen as mere picnic nuisances, the UK is home to a surprising variety of wasps, including both social and solitary species. While many of us will be familiar with the iconic black and yellow social wasps, numerous solitary species display incredible diversity in both form and behaviour. Distinguishing them can seem daunting, but key features like body shape, coloration, and reproductive behaviour can offer valuable clues.

Here, we’ll explore a selection of common wasp species, and some wasp families found across the UK, detailing their identifying characteristics and the typical habitats they can be found in.

Common European Yellowjacket (Vespa vulgaris)

Identification: Between 11-19mm in length with striking black and yellow stripes. These social wasps have six abdominal sections, each with one stripe, and there is a very distinguished waist between the thorax and the abdomen, which has black dots and rings. The species has a conspicuous face on a triangular shaped head with a black anchor or dagger shaped mark towards the base, and a pair of long, robust antennae. They have yellow cheeks and yellow legs.

Distribution: Widespread throughout the UK. Common Social Wasps can be found in almost all habitats, particularly grassland, heathland and woodland from mid-March to November.

Red Wasp (Vespula rufa)

Identification: Growing up to 20mm in length, Red Wasps can easily be distinguished from V. vulgaris by reddish-brown markings on their upper back segments.

Distribution: Widespread, and frequently found in open woodland, moorland and hedge banks from the end of March until September.

Hornet (Vespa crabro)

Identification: Hornets are Britain’s largest social wasp species. Around 15-35mm in size. The abdomen is yellow and unbanded, with brown markings on the upper parts, while the thorax is black and reddish-brown. Their legs are a reddish brown – a characteristic that can distinguish them from Asian Hornets – and antennae are yellow or brown in colour.

Distribution: Widespread distribution and commonly found throughout England and Wales. Hornets can be found in many lowland habitats and are known to associate with ancient woodland, wood pasture and can be found in parks and gardens in more urban areas. Queens emerge from overwintering in early April, while workers can typically be seen from late June to November.

Yellow-legged Asian Hornet (Vespa velutina)

Asian hornet by Gilles San Martin, via flickr.

Asian hornet by Gilles San Martin, via flickr.

Identification: Typically smaller than native hornets, this invasive species can grow up to 3cm in length. Their abdomen is dark in colour with fine yellow stripes, and the fourth segment towards the base of the hornet is distinctly yellow orange in colour, while the thorax is entirely black or dark brown and appears velvety in texture. From the front, the head appears orange and the legs have yellow tips.

Distribution: Yellow-legged Asian Hornets were first recorded in England around 2016, after they were accidentally introduced from Asia. They have mostly been recorded in the south of England, particularly the South-east.

Wasp Families

The diversity of wasp families in the UK is vast and presents a significant identification challenge. In this blog, we have chosen to focus on a number of wasp families to demonstrate the wonderful diversity of this group.

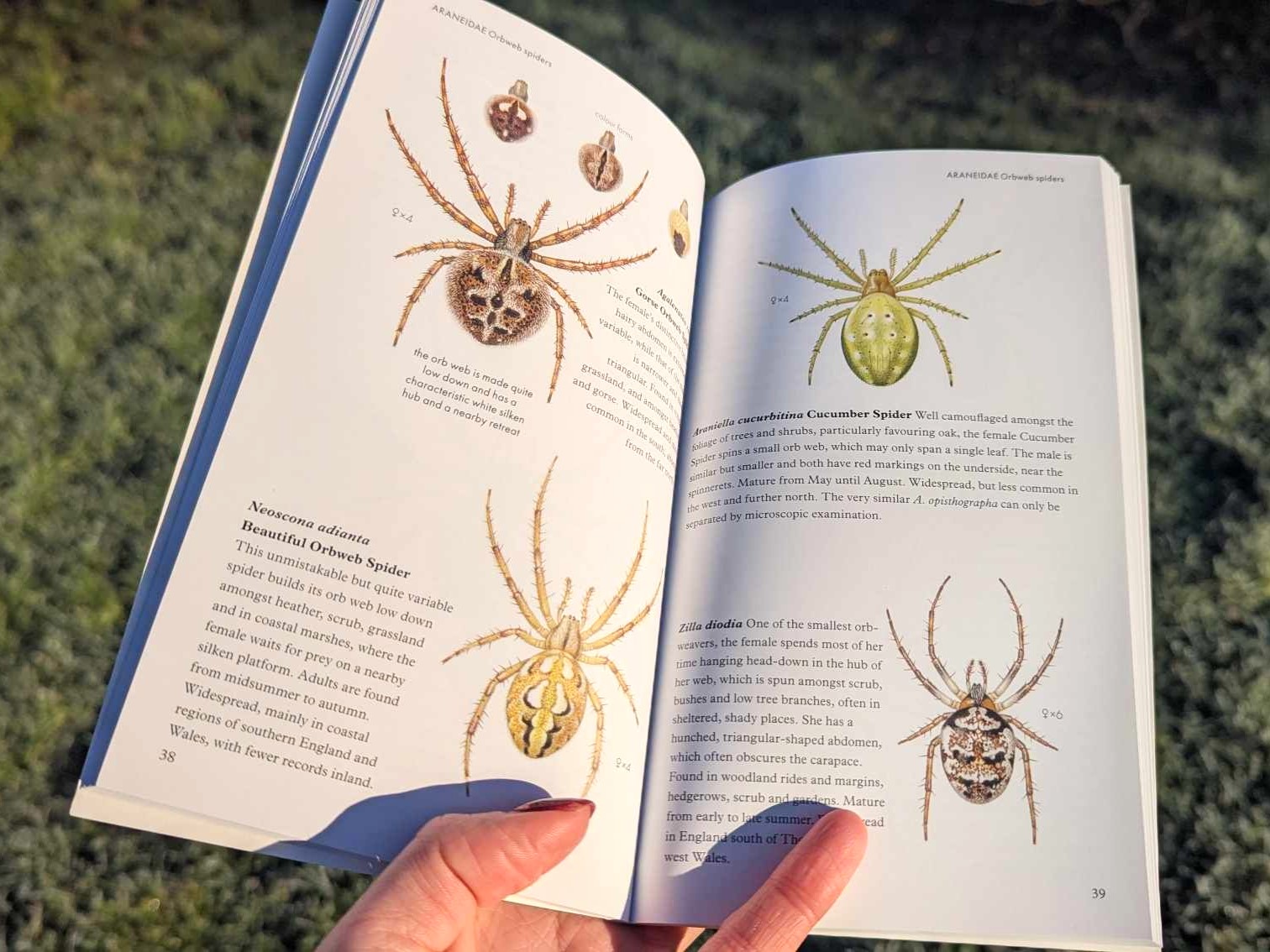

Ichneumon Wasps

There are around 2,500 species of Ichneumon wasp in the UK. These small insects can vary in size but generally reach up to 1 ½ inches in length. They exhibit a wide range of colours and patterns, some with brightly coloured bands, and others with more subtle markings. Ichneumon Wasps can be distinguished by a slender sickle-shaped abdomen and a pair of long antennae, each with at least 16 segments. They have a narrow waist, long jointed legs and two pairs of wings. These parasitic wasps inhabit flower-rich meadows, gardens and woodland – they can often be seen around umbellifers or investigating vegetation and dead wood.

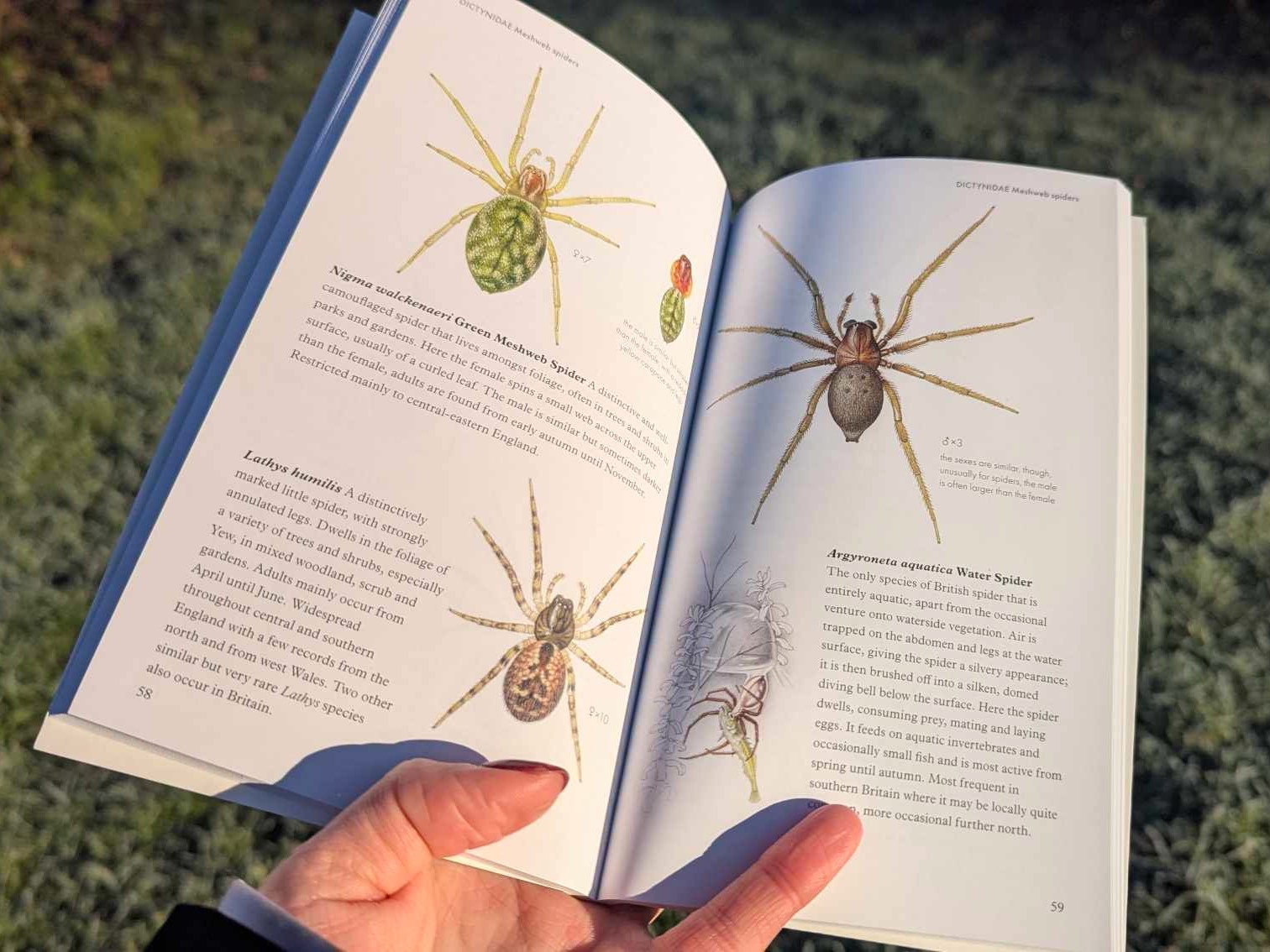

Gall Wasps

The UK is estimated to have 86 Gall Wasps, a group of well-studied parasitic wasps. This group gets its name for a unique reproductive behaviour where adults lay eggs in the soft tissues of trees, flowers and other plants, creating a gall as the larva develop. Usually on the underside of leaves, branches and around acorns, these wasps produce conspicuous galls on their host plant – interestingly, they usually only infect a specific species of genus, for example, Citrus Gall Wasps will exclusively parasitise citrus trees. After overwintering, the larvae will emerge in spring and can be seen throughout summer. They are typically under 5mm in size, shiny, and are black or brown in colour with a humped thorax and wings.

Cuckoo Wasps

Instantly recognisable by their brilliant metallic body colours in shades of blue, green, purple and red, these small chrysidids are also known as jewel or ruby tailed wasps. There are around 31 species of Cuckoo Wasp in the UK, which can be seen in sunny weather from April to October in a range of habitats; particularly in sandy soils around coastal areas, gardens and ancient woodlands. The group are often seen investigating the nests of other Hymenoptera species in order to reproduce – these parasitic species will enter the host nest and lay their own eggs in the host cells. Once hatched, Cuckoo wasp larvae will eat the eggs and larvae of the host species before restarting the cycle – hence the name ‘cuckoo’.

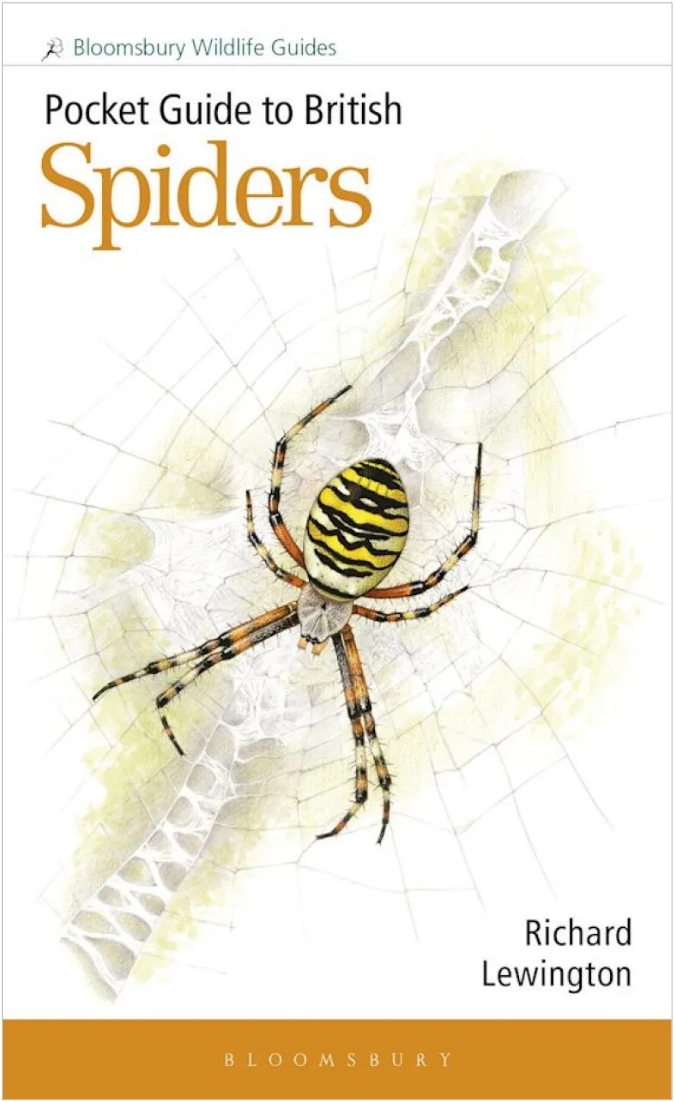

Recommended Reading:

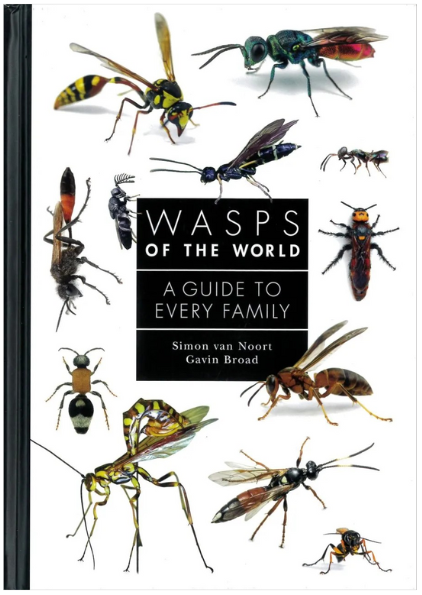

Wasps of the World | Feb 2024

A richly illustrated guide to wasps around the world, providing a breathtaking look at the characteristics, habitats and lifestyles of these extraordinary insects.

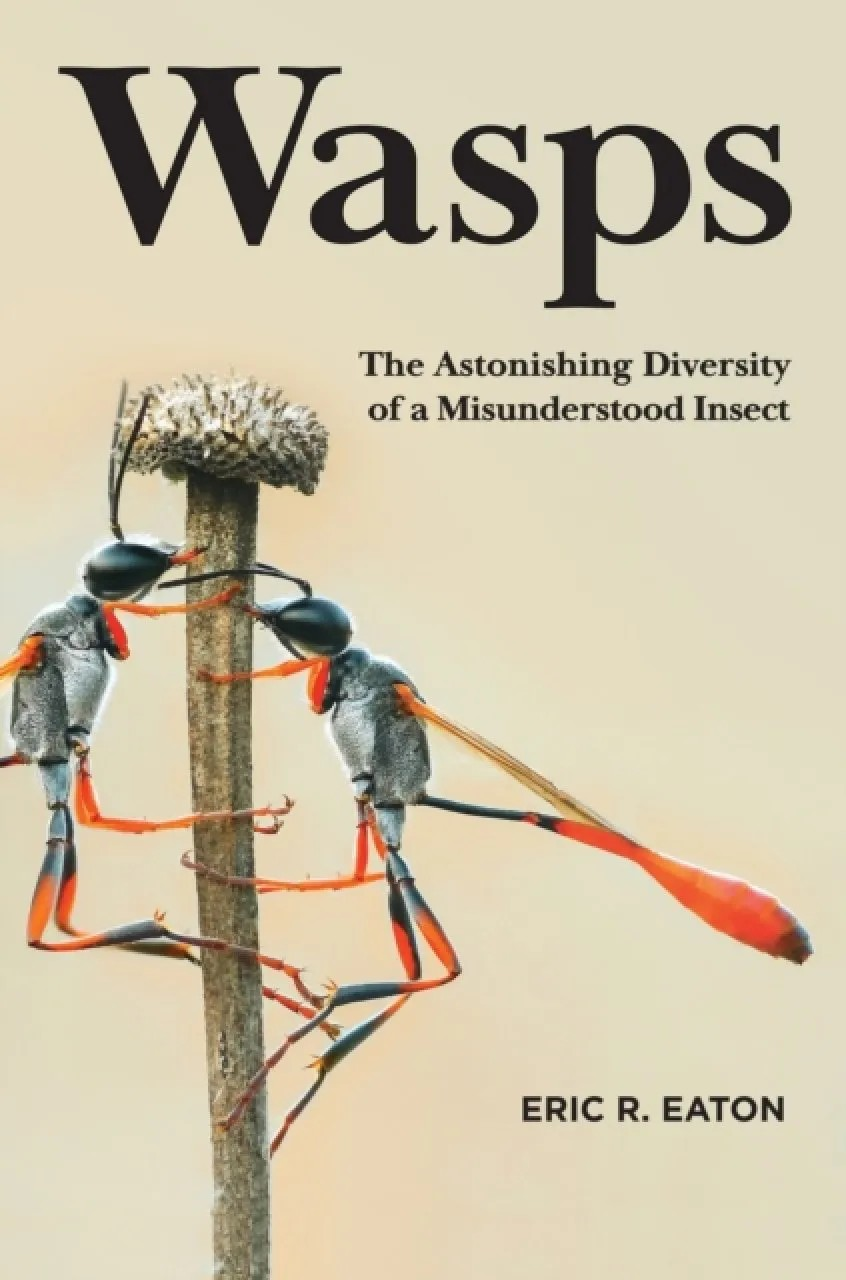

Written by a leading authority on these remarkable insects, Wasps reveals a world of staggering variety and endless fascination and is packed with over 150 incredible colour illustrations.

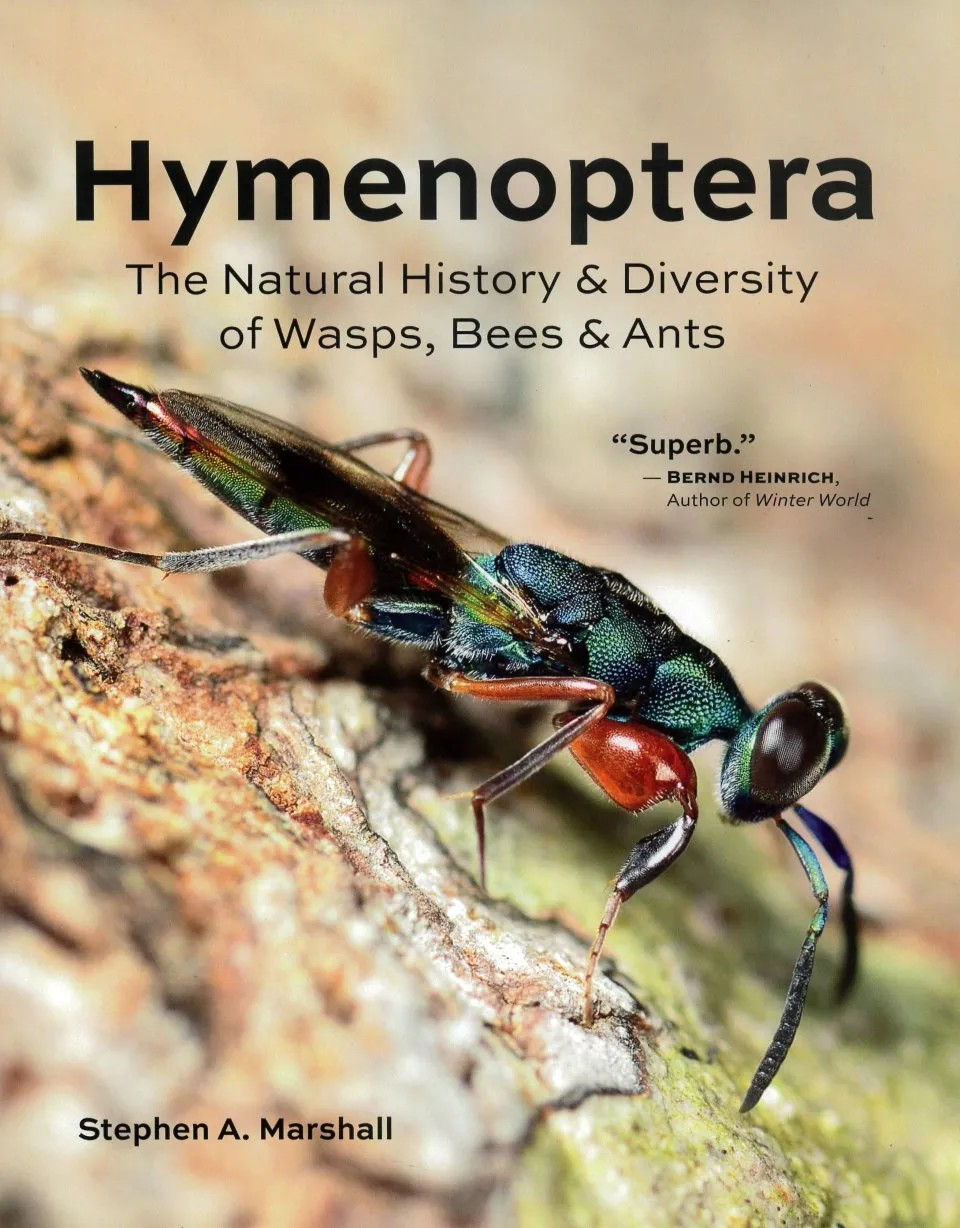

Hymenoptera | May 2023

Comprehensive and packed with richly illustrated keys and thousands of colour photographs, this volume provides the reader with an enjoyable introduction to a huge group of organisms.

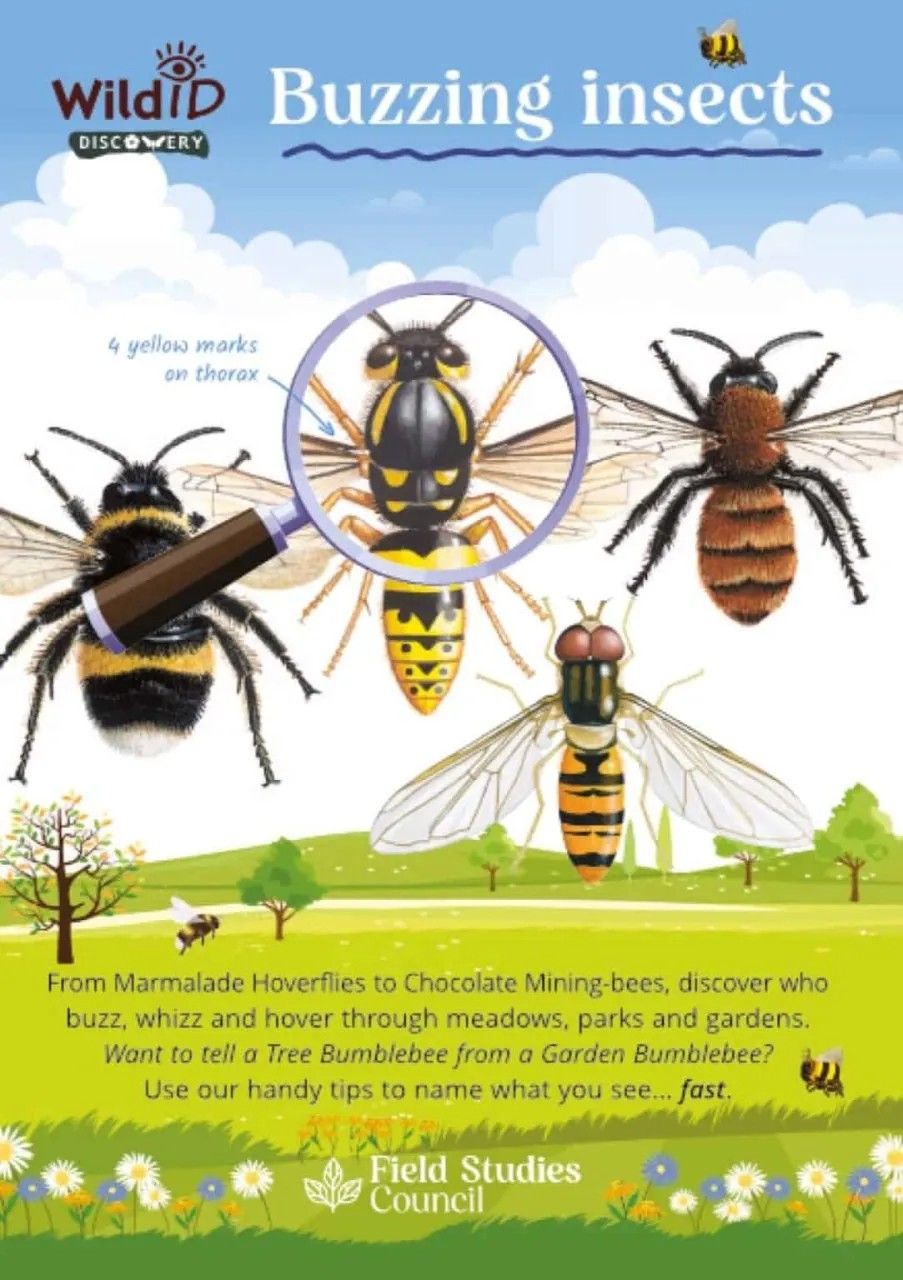

FSC Discovery Guide: Buzzing Insects | March 2025

From Marmalade Hoverflies to Chocolate Mining-bees, discover 30 stripy insects that buzz, whizz and hover through meadows, parks and gardens with this compact fold-out guide.