This lavishly illustrated and comprehensive book marks the 150th volume in the renowned New Naturalist series, and details the wildlife, landscapes and natural history of Exmoor to reveal its incredible biodiversity. As someone actively involved with the environment of the South-West, the author provides the reader with a scholarly yet accessible volume on this abundant area.

This lavishly illustrated and comprehensive book marks the 150th volume in the renowned New Naturalist series, and details the wildlife, landscapes and natural history of Exmoor to reveal its incredible biodiversity. As someone actively involved with the environment of the South-West, the author provides the reader with a scholarly yet accessible volume on this abundant area.

Flemming Ulf-Hansen is an ecologist with nearly 37 years of experience working in wildlife conservation, primarily across Exmoor and Salisbury Plain. He is the founding chair of the Exmoor Mires Project and specializes in ecological restoration, with a host of expertise in grassland, woodland, and heathland management, as well as invasive species control. He joined the Nature Conservancy Council in 1988 and was awarded a Churchill Fellowship in 2010 to study habitat restoration.

Flemming Ulf-Hansen is an ecologist with nearly 37 years of experience working in wildlife conservation, primarily across Exmoor and Salisbury Plain. He is the founding chair of the Exmoor Mires Project and specializes in ecological restoration, with a host of expertise in grassland, woodland, and heathland management, as well as invasive species control. He joined the Nature Conservancy Council in 1988 and was awarded a Churchill Fellowship in 2010 to study habitat restoration.

We recently spoke to Flemming about Exmoor, where he explains why a book on this area was needed, how rewilding may benefit this vital landscape, what he’s currently working on and more.

Volume 27 of the New Naturalist series, the first to explore Dartmoor, was published over 70 years ago. Why do you feel that a title on Exmoor was important to produce?

Exmoor’s wildlife has been neglected in published work for over 40 years, with perhaps the exception of the battles over heathland ploughing. Since the 1953 Dartmoor title, we have had a second volume in 2009, by Ian Mercer. Exmoor is one of the three moorlands in southern England, the other being Bodmin Moor – and one that spans the upland-lowland boundary. But it has a special ingredient – the coast! Exmoor’s somewhat remote location on the north coast of Somerset and Devon means that its wildlife has had less attention. With only Minehead, Dulverton or Combe Martin close by, there is no great supply of recorders in major towns or cities. An additional goal has been to highlight unpublished or grey literature, ensuring that this valuable information is accessible and not overlooked.

Exmoor National Park supports a wide range of habitats: blanket bogs, dry heath, scrub and peatland to name just a few. Why is this landscape so vital and what is its ecological value in the UK?

The elements of a moorland landscape you highlighted were the main reason for the designation of the National Park. Its position as an upland massif on the western seaboard gives it a distinctiveness with a disposition of low- and higher-altitude communities, perhaps unique to southwest England. The western heaths can locally dominate the landscape, and the vibrant purple and yellow colours of flowering heathers and Western Gorse are a treat in early autumn which harbour Stonechat and Dartford Warbler. Well-developed mosaics and transitions between moorland and woodland are a feature and provide structure, shelter and rich foraging habitat for wildlife, including a home for some special species, like the Heath Fritillary butterfly.

The woods should also be highlighted. Their position on the west coast of the British Isles brings moisture and a mild climate associated with the Gulf Stream. For many fungi, bryophytes and ferns these are ideal conditions, and Exmoor’s lichens reach international importance. Large sheets of western mosses and liverworts carpeting rocky ground among abundant ferns are Exmoor’s equivalent of lowland Britain’s much-vaunted Bluebell woods. They have been recently identified as temperate rainforest, placing them in a wider context.

Exmoor is not typically known for its coastline – did the limited accessibility of this environment pose challenges in researching and writing Chapter 8?

It should be better known, as it is one of its high points! But yes, the steepness of the cliffs, including England’s highest at Great Hangman, combined with few rivers cutting down to the sea to allow safe access, has deterred much survey work. It has meant that, for example, cliffs are surveyed from a boat with binoculars. Spotting whitebeams is just about possible, but identifying rare or endemic members of the group is not. It was an ambition of mine – yet to be realised – to try and age cliff-edge Yews which were noted as far back as 1874 by the Midlands botanist Edwin Lees, at Combe Martin. The climbers who pioneered the Exmoor Traverse knew some of the locations well, the largest of which is probably at Wringapeak. They may well hold some surprises and form a reservoir of ancient trees and remnants of unspoilt natural woodland.

In the marine environment there is no doubt that severe tides have limited exploration. I have had to rely on old data or records from very scattered locations. There is just one place where the seashore or seabed can be reached, Glenthorne, in the 12 km stretch of remote coast between Gore Point and The Foreland on the Devon side.

Chapter 10 highlights the increasing popularity of ‘rewilding’ approaches, a prime example being the Knepp Estate in West Sussex. How do you think this method might benefit Exmoor, and what recommendations might you have for a rewilding approach?

Parts of Exmoor are of course deliciously wild, they are just not easy to see –the steep slopes and cliffs for instance. Of course, rewilding has in effect been happening on parts of Exmoor anyway, just not by design – I am thinking about originally open, marginal land transitioning to secondary woodland over the last 50–100 years.

To restore more wildlife to Exmoor, we will need to embrace fundamental ecosystem processes across larger areas of wilder, semi-natural habitats with more wetland and forest. The range of approaches is great, and we should not be too purist. In some areas active intervention may be needed, such as by introduction of beavers or other herbivores. In other areas we can adopt ‘agricultural rewilding’, which aims to restore ecosystem functions using lower-intensity human interventions, such as the management and harvest of livestock.

The Exmoor Nature Recovery Vision is an ambitious vision for a thriving, diverse landscape on Exmoor. What are the first steps to achieving this vision in your eyes, and how realistic do you think this vision is?

We can’t continue to spend time tinkering with the status quo. We need a step change and swift action. This won’t be possible with cuts in budgets of statutory bodies and the National Park Authority. For example, cuts in Natural England staff dealing with protected sites have been drastic and persistent. Projects relying on input of time have withered on the vine of neglect. Short-termism caused by short cycles of funding projects doesn’t help to achieve change in land management, which is a long-term game. Implementation is the key now, which requires partnership, appropriate tools and funding, and steadfast determination.

The vision is achievable but only with significant change in land away from the protected sites. These areas may not be perfect, but at least there are mechanisms in place to help. Exmoor’s farmed and enclosed land amounts to about 65% of the park, and much is agriculturally ‘improved’ land that has little wildlife interest. These areas could form a source of land for recovery, if the incentives and mechanisms are in place.

What are you working on next? Do you have any more writing projects lined up?

I have retired after nearly 37 years of working for the government’s wildlife body. I am going to tackle some tasks at home, as well as enjoy experiencing more nature by travelling a bit, before settling on another project.

Exmoor is available from our online bookstore here.

Susan Young is a photographer and writer based in South Devon, who has a wealth of experience in wildlife photography. She has authored several books, including

Susan Young is a photographer and writer based in South Devon, who has a wealth of experience in wildlife photography. She has authored several books, including

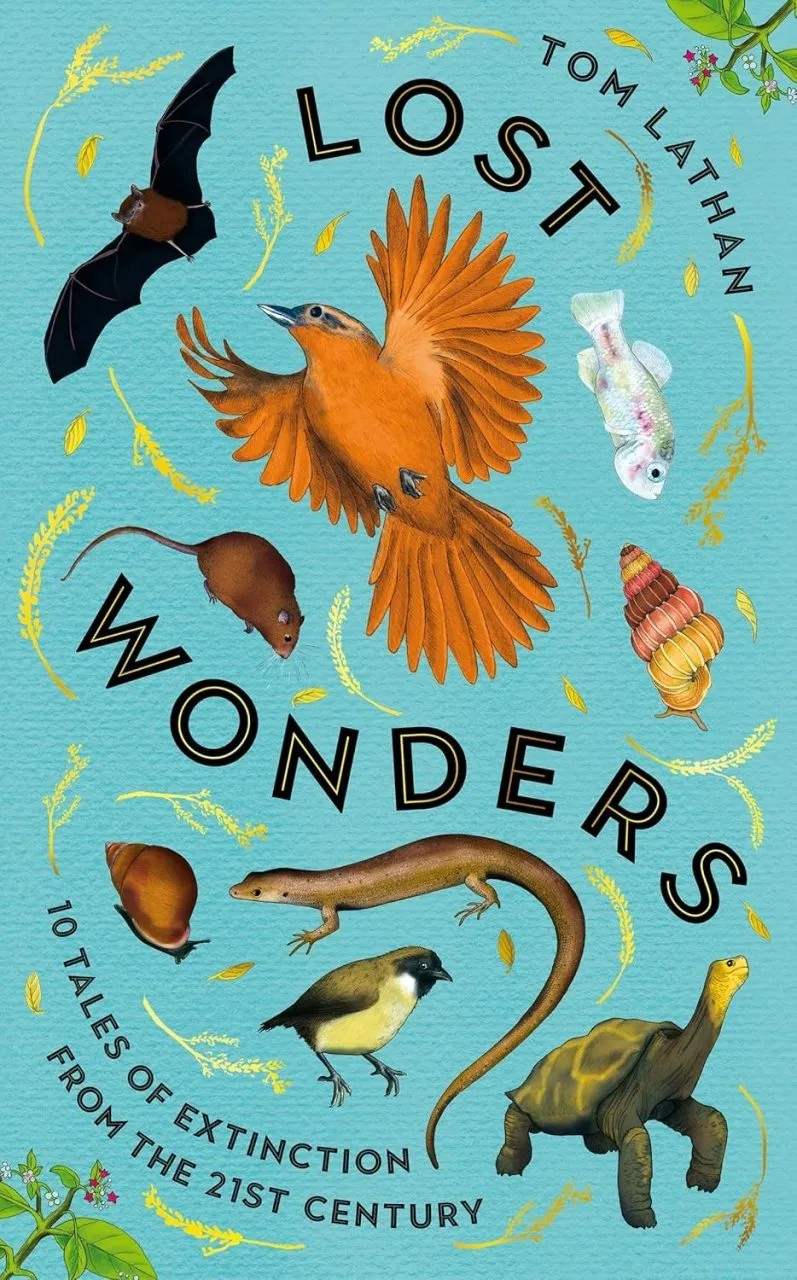

Taking a step back to compose myself I do, however, have two points of criticism; or, if not criticism, two points I feel have been omitted. First, there is the proximate question of whether trying to save a species at all costs is always the best use of the limited time, money, and other resources available for conservation. Not everybody agrees it is, and e.g. Inheritors of the Earth provocatively argued that island species are evolutionary dead ends, vulnerable to invasion. Are resources better spent on populations that still stand a decent chance? A counterargument could be made that, yes, these attempts *are* worthwhile because we learn how to improve our protocols, techniques, and technologies for the inevitable next extinction. My point is that Lathan does not broach these questions here. I would have loved for him to wrestle with these and put them to his interviewees. Second, there is the ultimate question of what it would take to turn the tide of extinction, of what such a world would look like. I judge him less harshly on this because very few authors seem willing to mention the root causes that got us here. His interviewees gave him several openings at broaching thorny topics that he did not pursue. This is another set of questions where both his views and those of his interviewees could have further enriched the book.

Taking a step back to compose myself I do, however, have two points of criticism; or, if not criticism, two points I feel have been omitted. First, there is the proximate question of whether trying to save a species at all costs is always the best use of the limited time, money, and other resources available for conservation. Not everybody agrees it is, and e.g. Inheritors of the Earth provocatively argued that island species are evolutionary dead ends, vulnerable to invasion. Are resources better spent on populations that still stand a decent chance? A counterargument could be made that, yes, these attempts *are* worthwhile because we learn how to improve our protocols, techniques, and technologies for the inevitable next extinction. My point is that Lathan does not broach these questions here. I would have loved for him to wrestle with these and put them to his interviewees. Second, there is the ultimate question of what it would take to turn the tide of extinction, of what such a world would look like. I judge him less harshly on this because very few authors seem willing to mention the root causes that got us here. His interviewees gave him several openings at broaching thorny topics that he did not pursue. This is another set of questions where both his views and those of his interviewees could have further enriched the book.