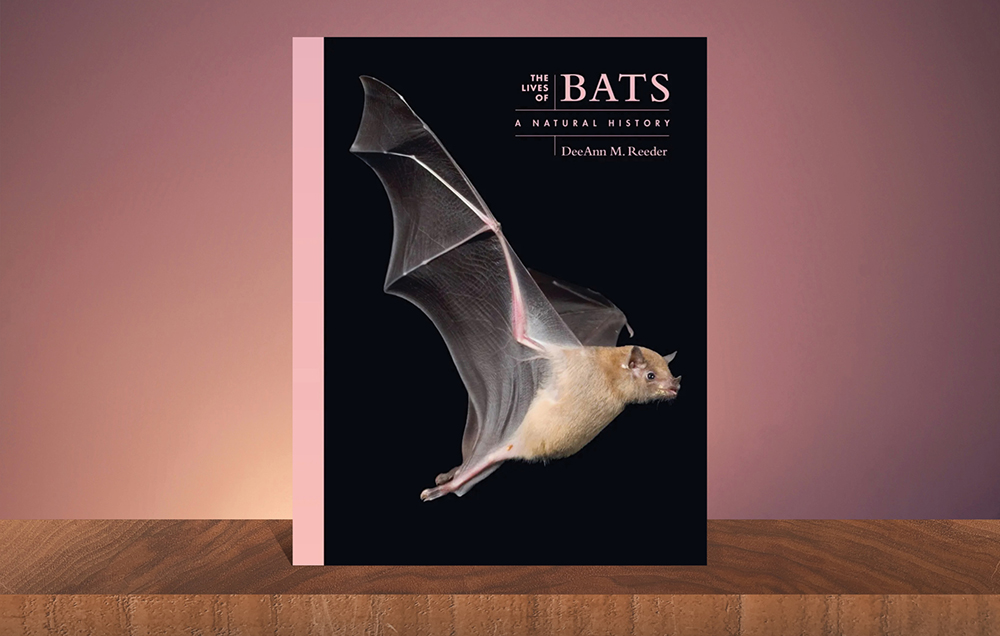

The Lives of Bats is part of Princeton University Press’s series The Lives of the Natural World that has grown to 14 volumes. Technically speaking, it is designed and produced by UniPress Books, which I have described elsewhere as the spiritual successor of Ivy Press and which is similarly known for producing good-looking books. As with the other volumes, this one is chock-a-block with full-colour photos, to the point that you would be hard-pressed to find a single page of plain text. It follows the same formula as other volumes, ending each chapter with a short species gallery that profiles four or five relevant or noteworthy species.

The Lives of Bats is part of Princeton University Press’s series The Lives of the Natural World that has grown to 14 volumes. Technically speaking, it is designed and produced by UniPress Books, which I have described elsewhere as the spiritual successor of Ivy Press and which is similarly known for producing good-looking books. As with the other volumes, this one is chock-a-block with full-colour photos, to the point that you would be hard-pressed to find a single page of plain text. It follows the same formula as other volumes, ending each chapter with a short species gallery that profiles four or five relevant or noteworthy species.

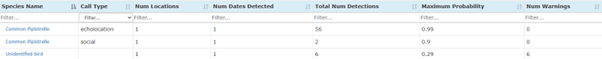

Professor of biology DeeAnn M. Reeder’s research programme encompasses physiology, immunology, disease ecology, behaviour, evolution, and conservation, and bats are often her model organism of choice. She is only all too aware of the dislike and fear that bats instil, especially as reservoir hosts of diseases, so an important focus of this book is to demystify and (if that is even a word) de-demonise bats by giving a factual and up-to-date primer on their biology. After a brief introduction, Reeder picks seven topics—evolution, anatomy, echolocation, diet, thermoregulation, reproduction, and disease—before ending with a chapter on past and present interactions between bats and humans.

If there is a unifying theme to this book, it is how much the biology of bats is shaped by the demands of flight. Anatomical adaptations are the first to come to mind, from the ankle spur (a calcar) that supports the wing membrane between the hind limbs (the uropatagium), to the five extra muscles that control the tautness and curvature of the wing membrane. Reeder’s favourite overlooked adaptation is the hind limbs that are rotated 180°, meaning the soles of the feet face forward and the knees bend backwards compared to other mammals.

The demands of flight extend far beyond anatomy, though. To conserve energy, bats can go into torpor, lowering their metabolic rate and body temperature. This can be as brief as a few hours or be extended for weeks on end, at which point we call it hibernation. Like humans, bats generate their own body heat (endothermy), but unlike us, they can conserve energy by allowing their body temperature to track the environmental temperature (heterothermy) while we maintain a steady body temperature (homeothermy). The need for energy conservation even impacts their reproduction. Bat pups are huge compared to their parents, meaning pregnancy is energetically costly on two fronts: foetal development takes energy, but so does flying around with all that extra mass. To make sure birth coincides with peak food availability, female bats can store sperm (a well-known trait in many organisms) but also slow down or even pause (!) foetal development.

Reeder features many other notable traits, adding an extra layer of information to the basic facts that will be rattling around in most people’s heads. Sure, bats echolocate, but what I did not realise is that some groups emit sound out of their mouth and others out of their nose. The family Pteropodidae, the fruit bats, have lost echolocation (fruit tends not to move), yet some species have secondarily re-evolved it, relying on wing-clapping or tongue-clicking to help them navigate their cave roosts. And where many bats issue a call and then listen out for the echo, some bats do not separate the two in time but in frequency, calling at a different frequency than the echoes return at. This nifty feat of sensory biology allows them to produce sound while simultaneously receiving and interpreting the incoming echoes.

I also came away from this book with a much better appreciation of the family Phyllostomidae. When the University of Chicago Press published a book dedicated to this family in 2020, I was admittedly nonplussed: what is so special about them? The incredible diversity of their diet. This family includes carnivorous bats dining on small reptiles, birds, and mammals. It includes the three species of vampire bat whose sanguivorous habits have become the stuff of legend. More relevant but less appreciated is that, by eating fruit, pollen, and nectar, they are important pollinators, including of many cacti and important crops.

Reeder is at her most strident when it comes to the role of bats in diseases, including COVID-19. Yes, bats harbour viruses and other pathogens that impact public health, but spillovers are a human problem caused by our relentless destruction of wildlife habitat. We should be wary of “the sometimes sensationalistic portrayal of bats, writ large, as hosts of deadly viruses” (p. 250); the same can be said of many other animal groups, including primates, rodents, and birds. Reeder is a proponent of the One Health framework that recognises that you cannot tackle human, animal, and ecosystem health in isolation because they are all interconnected.

Given the format and aim of this series, Reeder only has the space to go so deep on these and other topics. However, as with the book I reviewed previously, this is not just a regurgitation of popular information. You can tell this is written by a specialist in her field who is carefully weighing up how much information to give you and how much to hold back. The resources section recommends some of the many technical books if you want to read deeper, plus a two-page reference section to journal articles, including studies up to 2023 and 2024.

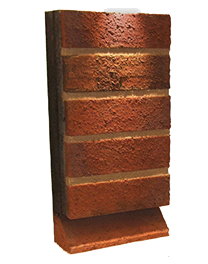

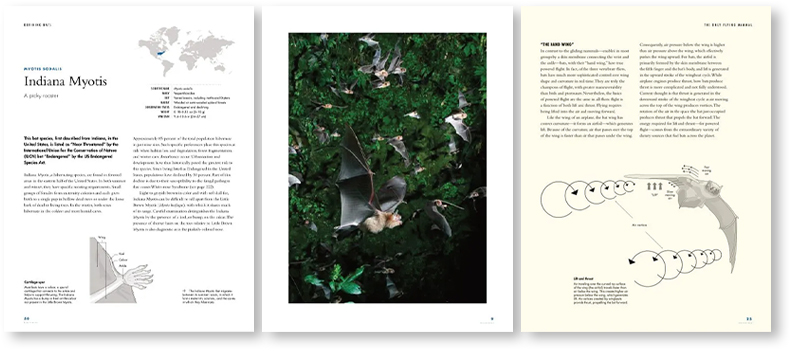

Bats are particularly photogenic, and the editorial team at UniPress Books has scoured several stock photo libraries, as well as the work of numerous individual photographers, credited in the back of the book. There are memorable photos here while a small number of neat infographics are contributed by illustrator Sarah Skeate.

The Lives of Bats continues the series’ successful formula: challenge one or two subject experts to write an accessible introduction that can serve multiple audiences. For novices, this is a great first stop on bats that will give you a well-informed introduction to their unique biology (and equally, it is a book that you can safely gift them). However, the book is also rewarding for biologists who just happen to have studied other organisms but have a hankering for bats. I enjoyed The Lives of Bats more than I thought I would, and by the end, I felt it had subtly enriched my knowledge.