How to watch bats

Watching bats can be a fascinating and rewarding hobby. If you want to go out and watch bats yourself, you may not have to travel as far as you think. Bats live all over the UK in the countryside, towns and cities. Head down to your local patch of woodland, park or even your own back garden around sunset and watch the sky. Some bats fly quite high in the sky around the tops of trees, others fly lower, even at eye level. If you have a large pond, river or lake nearby, watch the surface of the water and you might see a Daubenton’s bat skim across the surface catching insects. Warm, dry and relatively still nights are best when it comes to bat watching. You are more likely to see bats around sunset and sunrise and they can be seen between March and October.

An Introduction to Bat Detectors

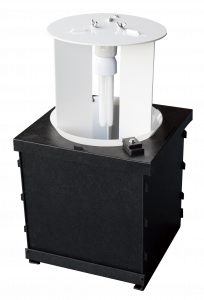

To really immerse yourself in the world of bats, it is worth using a bat detector.

Bats use calls for communication, navigation and hunting but these are at frequencies above that of most human hearing. So even if you’re watching dozens of bats above you, you’re unlikely to be able to hear their calls. Bat detectors are devices that convert these ultrasonic calls into audible sounds and because different bat species call at different frequencies, bat detectors can even help you identify which bat is calling. Bat detectors are great fun to use and can help you learn a lot about bats. There are several different types of bat detectors on the market, at varying prices and with varying features. We’ve highlighted some of our favourite, entry-level bat detectors below.

Magenta 4 & Magenta 5 – Heterodyne

Our most popular range of beginner detectors are the Magentas. The Magentas are incredibly easy to use with a frequency dial to allow you to tune to a certain frequency, a front-facing speaker so that you can hear the converted bat calls, and a volume dial. They use a method of call processing called Heterodyne which works by tuning to one frequency at a time. The only difference between the Magenta 4 and the Magenta 5 is that the 5 has a digital display of the frequency that you are tuned to whereas the 4 has the frequencies on the tuning wheel which is lit by a small light. You can use Magentas with headphones and even record the outputted calls with a recorder (available separately).

Batscanner – Super-Heterodyne

The Batscanner is one of the easiest detectors to use, automatically scanning the whole frequency range and adjusting accordingly when it detects a bat, displaying the peak frequency on the digital display. This means you don’t have to tune anything and you won’t miss a bat because you’re tuned to the wrong frequency. The call output is clear and the Batscanner intelligently filters out non-bat low frequency calls giving you a clean, noise-free output.

Baton & Duet – Frequency Division

The BatBox Baton is perhaps even more simple to use than the Magentas, with just 1 button operation – the on/off button. You do not need to tune this detector – it will automatically detect all frequencies simultaneously as it works through ‘frequency division’, where all ultrasonic calls are divided by a factor of 10, pushing them into the human hearing range. Audio is played through the front facing speaker and when the Baton is plugged into a computer, you can see sonograms (visual representation of bat call) on the software included with the Baton.

The BatBox Duet is a similar but more sophisticated detector that is great if you want to take your bat detecting to the next level. It uses two modes of call processing: with heterodyne, you can tune the detector with the frequency dial and this is displayed on the backlit screen, much like a Magenta, but the detector also processes the ultrasonic sounds in frequency division mode and this can be captured using an audio recorder (available separately).

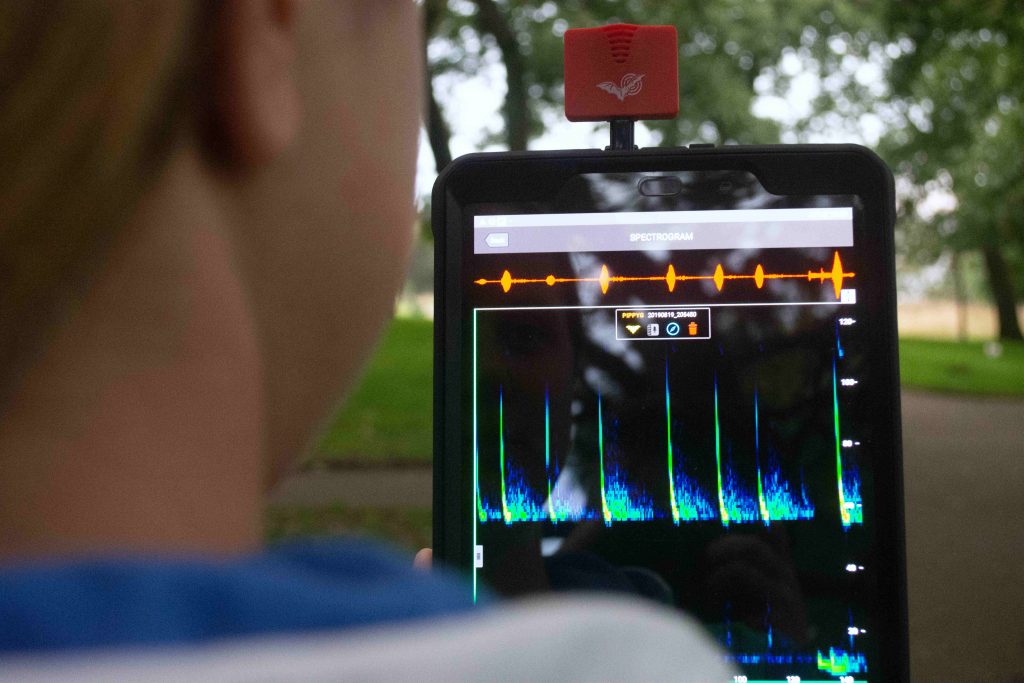

Echo Meter – Full Spectrum

The Echo Meter is a completely different type of bat detector but one that is very popular and has many amazing features, ideal for all levels of bat enthusiasts. It plugs into a compatible phone or tablet and with the help of a free app, turns your phone/tablet into a fully functional bat detector. The app displays live sonograms of bats and an intelligent algorithm identifies the most likely bat species based on the calls, all in real-time. The app can GPS tag your sightings and you can record, replay and download bat calls.

How can I help bats?

It is easy to encourage bats into your garden and there are many things you can do to help your neighbourhood bats. Have a read of our guide to helping your local bats for some ideas and inspiration. Things like putting up a bat box can help tremendously. It is often recommended to use wood concrete boxes which are made from a mixture of wood fibres and concrete. They are durable and they provide improved thermal insulation which benefits roosting bats. You can choose between cavity and crevice bat boxes based on the species you are trying to attract, for example, common pipistrelles prefer to roost in crevices.

The Lela Bat Box and the Gabriella Bat Box are wood concrete bat boxes designed to provide roosting space for a variety of crevice dwelling species. The Lela has two internal crevice chambers and the Gabriella contains one extensive single compartment.

The Isabella Bat Box is perfect for those cavity dwelling spcies you may want to encourage.

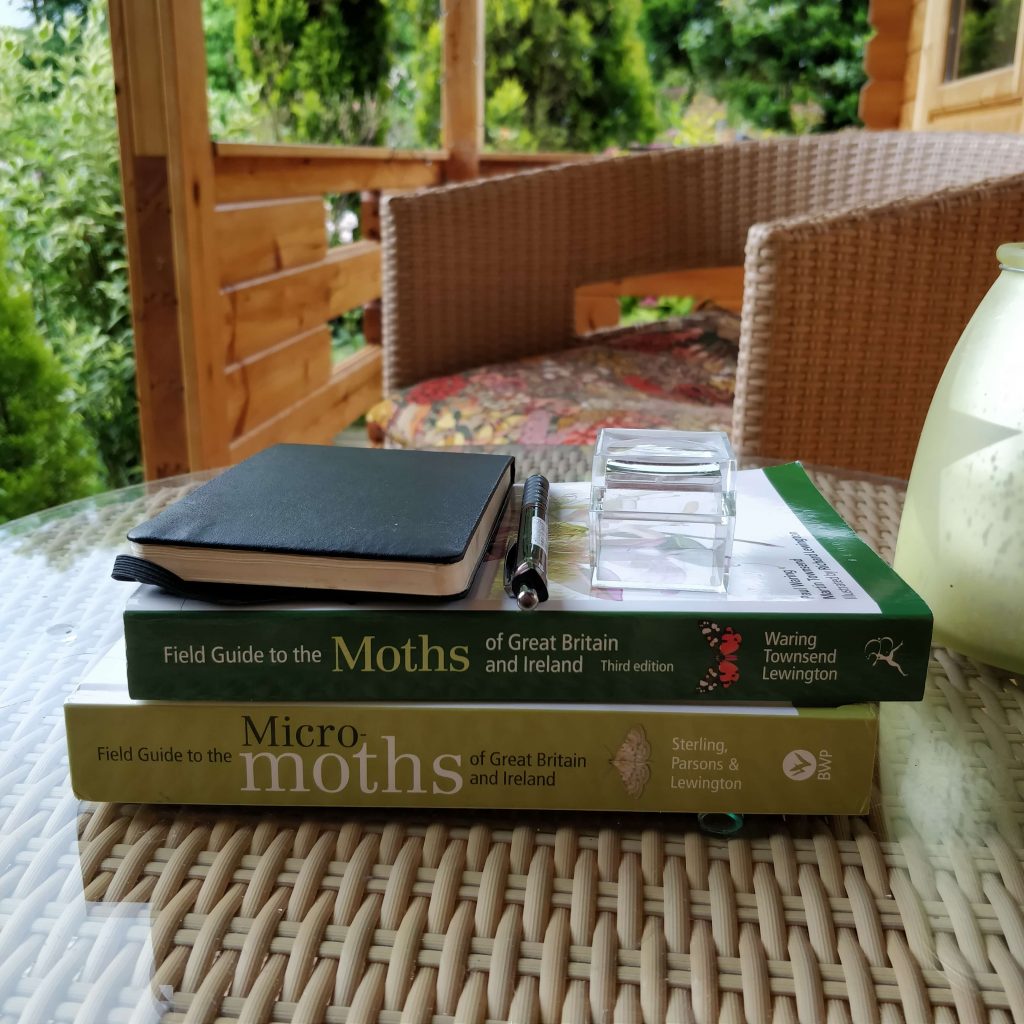

Other useful equipment and books

Listed below is some great kit and books to get you started or develop your knowledge on bat detecting and bat watching:

This DIY Bat Detector Kit has everything you need to build your own heterodyne bat detector. It is easy to assemble and does not require any soldering skills, simply follow the 34-page manual, available in both English and German.

This small, handheld audio recorder is ideal for plugging into your bat detector and recording the bat calls you are hearing. Recordings are stored on an SD card and can then be viewed on a computer to analyze further.

Nebo Mycro Rechargeable Headlamp

Nebo Mycro Rechargeable Headlamp

This handy rechargeable headtorch will help to keep your hands free when you’re trying to change settings or navigate in the dark. The Nebo Mycro has a bright, clean 150 lumen beam with easy-to-use mode and power buttons.

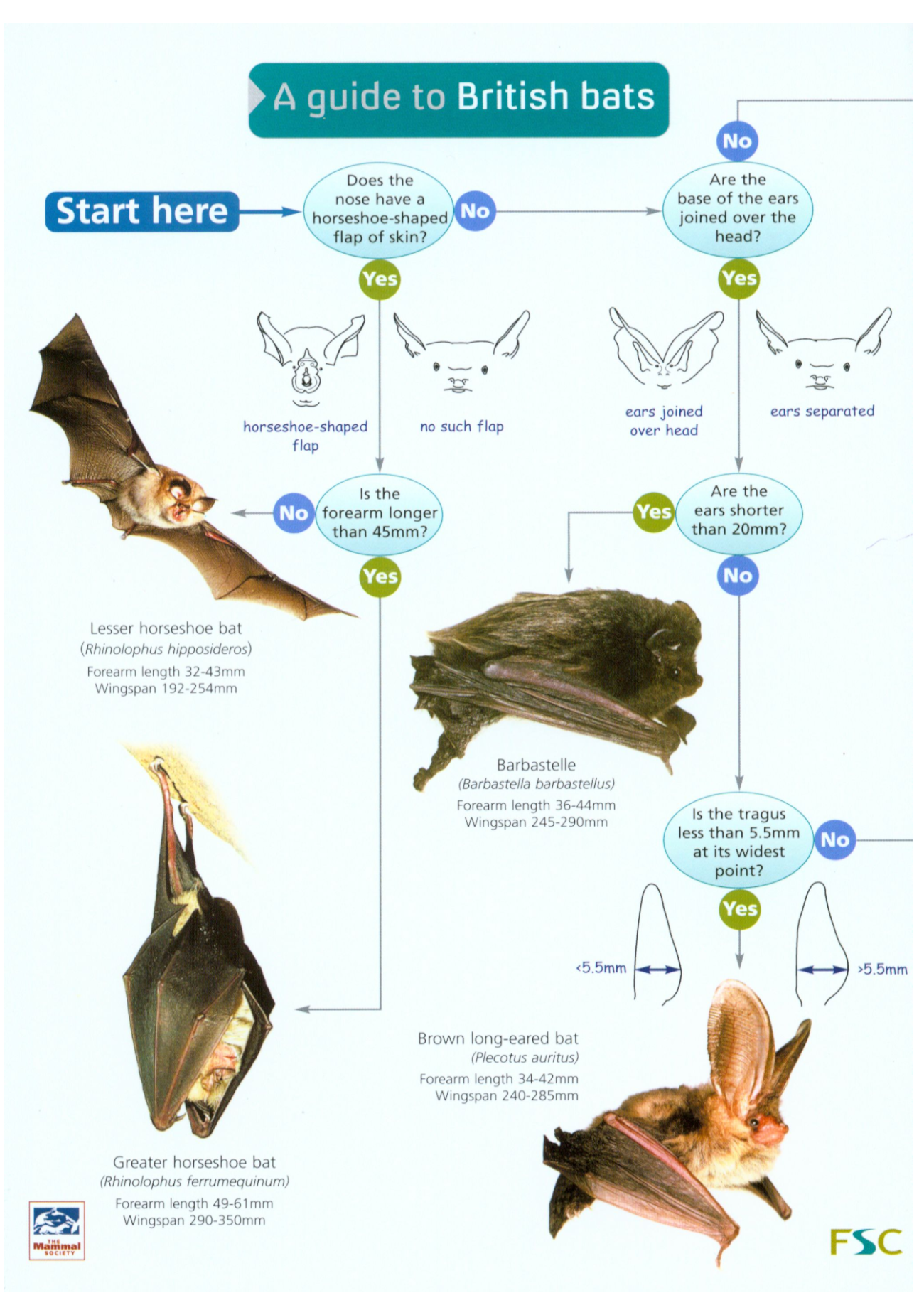

FSC’s ‘A Guide to British Bats’ is a fold out, laminated guide to help you identify bats through physical appearance and call frequency.

Bat Calls of Britain and Europe: A Guide to Species Identification

Bat Calls of Britain and Europe: A Guide to Species Identification

This practical guide is perfect for learning more about bat species identification, the equipment used and bat call analysis.

The Bat Detective: A Field Guide to Bat Detection

The Bat Detective: A Field Guide to Bat Detection

This field guide is perfect for beginners wanting to start learning how to identify bats from their calls. As each topic is explained references are given to the relevant tracks on the CD. The 48 tracks found here are the first ever compilation of British bat recordings on CD.

Could you tell us a little about your backgrounds and how you got interested in mycology?

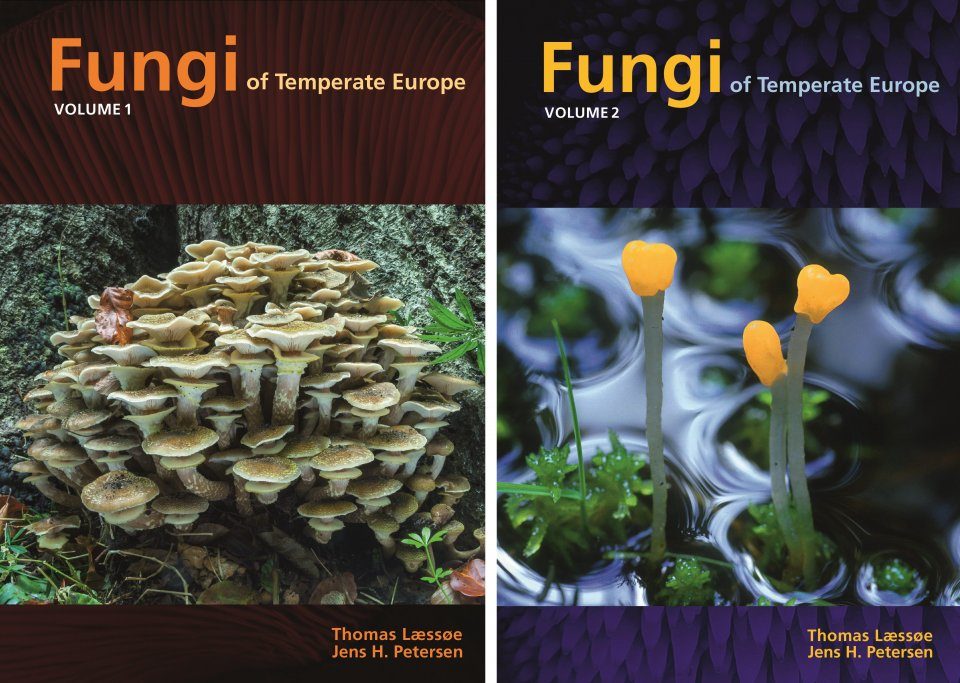

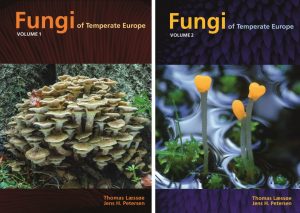

Could you tell us a little about your backgrounds and how you got interested in mycology?  Two volumes, totalling over 1,700 pages must have a been a considerable undertaking; can you let us know a little of the process and how long it has taken for this book to come to fruition?

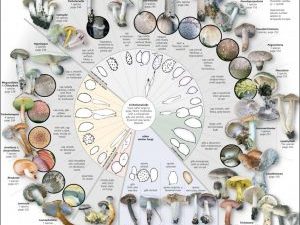

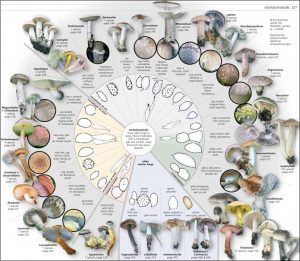

Two volumes, totalling over 1,700 pages must have a been a considerable undertaking; can you let us know a little of the process and how long it has taken for this book to come to fruition?  The book uses ‘form group’ to identify and present the fungi rather than exclusively strict taxonomic groups; what influenced you to use form groups and fungi wheels?

The book uses ‘form group’ to identify and present the fungi rather than exclusively strict taxonomic groups; what influenced you to use form groups and fungi wheels?  What is the biggest challenge when studying fungi?

What is the biggest challenge when studying fungi?  After such an endeavour you surely deserve a rest, but have either of you got any future projects planned that you can tell us about?

After such an endeavour you surely deserve a rest, but have either of you got any future projects planned that you can tell us about?

Dormouse Footprint Tunnels

Dormouse Footprint Tunnels

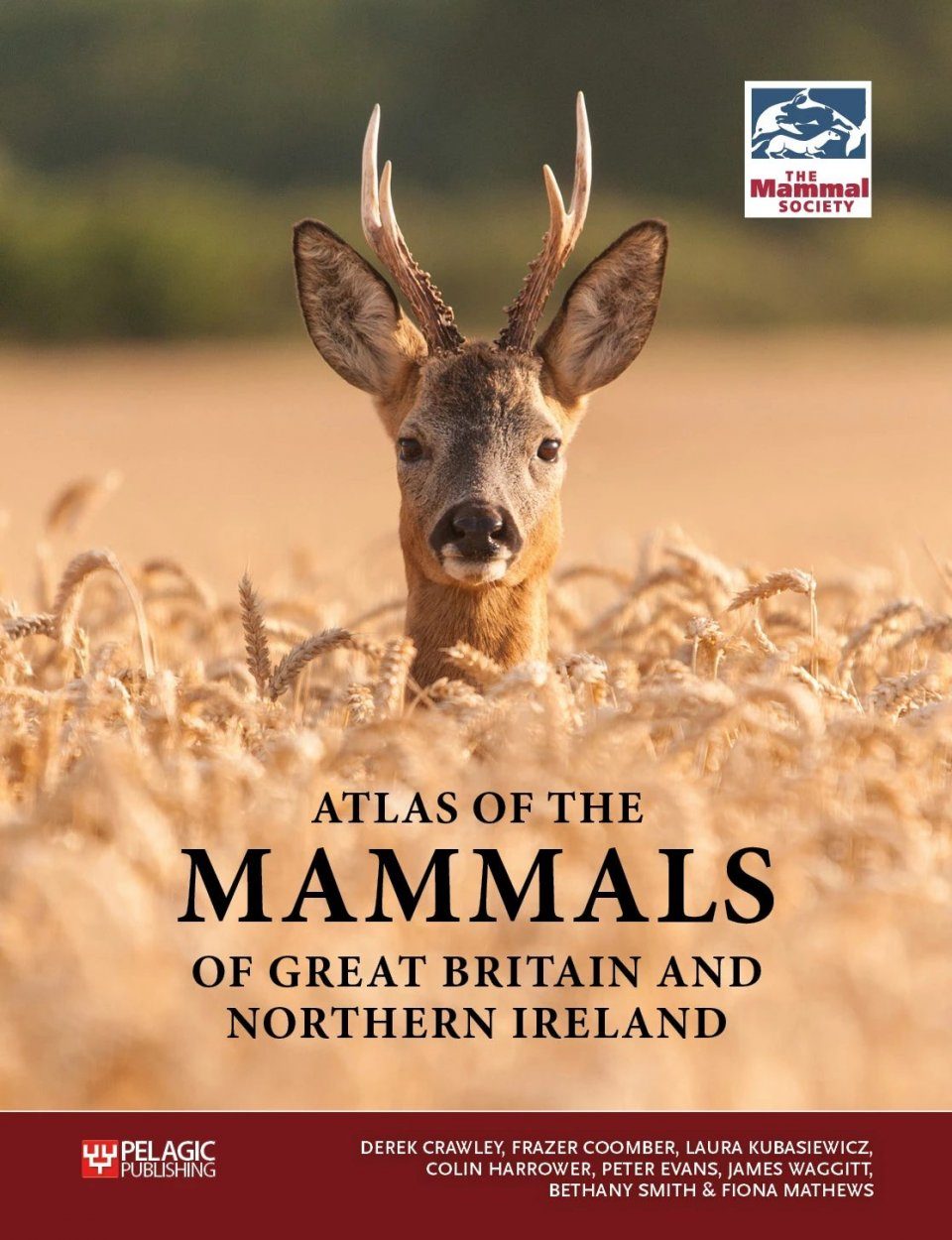

Live Trapping of Small Mammals

Live Trapping of Small Mammals

wanting to live in gardens?

wanting to live in gardens?