Recently we spoke to Helen Parr from the Devon Greater Horseshoe Bat Project about the wonderful work that is done in our local area for this rare species. Helen Parr also details the importance of conserving the Greater Horseshoe Bat, how we all can help ensure its survival and shares her hopes for the future.

Recently we spoke to Helen Parr from the Devon Greater Horseshoe Bat Project about the wonderful work that is done in our local area for this rare species. Helen Parr also details the importance of conserving the Greater Horseshoe Bat, how we all can help ensure its survival and shares her hopes for the future.

- For those who haven’t heard of the Devon Greater Horseshoe Bat project before, can you summarise what it is?

Our project works with local communities to secure a future for Greater Horseshoe Bats in Devon, their northern European stronghold. It is a partnership project of 18 organisations led by Devon Wildlife Trust and is supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, as well as other funders. The priority areas for the bat team are 11 maternity roosts around the county.

The countryside near the breeding roosts must provide everything that the bats need to survive and raise healthy young for the next generation. Their favoured foods are moths and beetles so they need good foraging and hunting grounds such as hedges, orchards, meadows, woodland edges and streams. Sadly we have lost 50% of our hedgerows and 98% of wildflower meadows in recent decades, so there is lots to be done! Working with landowners and farmers is a vital part of what we do.

2. What role do you play in the Devon Greater Horseshoe Bat project?

I’m the Community Engagement Officer on the project. Raising awareness and getting people involved is crucial so that when our project ends in autumn 2020, all the great work currently being done to help the bats will continue into the future.

My work with schools is one way to do this – children can work towards a series of Bat Buddy awards. They are always fascinated to learn about the Greater Horseshoe Bat; as a rare animal living on their doorstep, it has local relevance to them and they can make a practical difference at home or in their school grounds. Some of the children may be inspired to become our future conservationists!

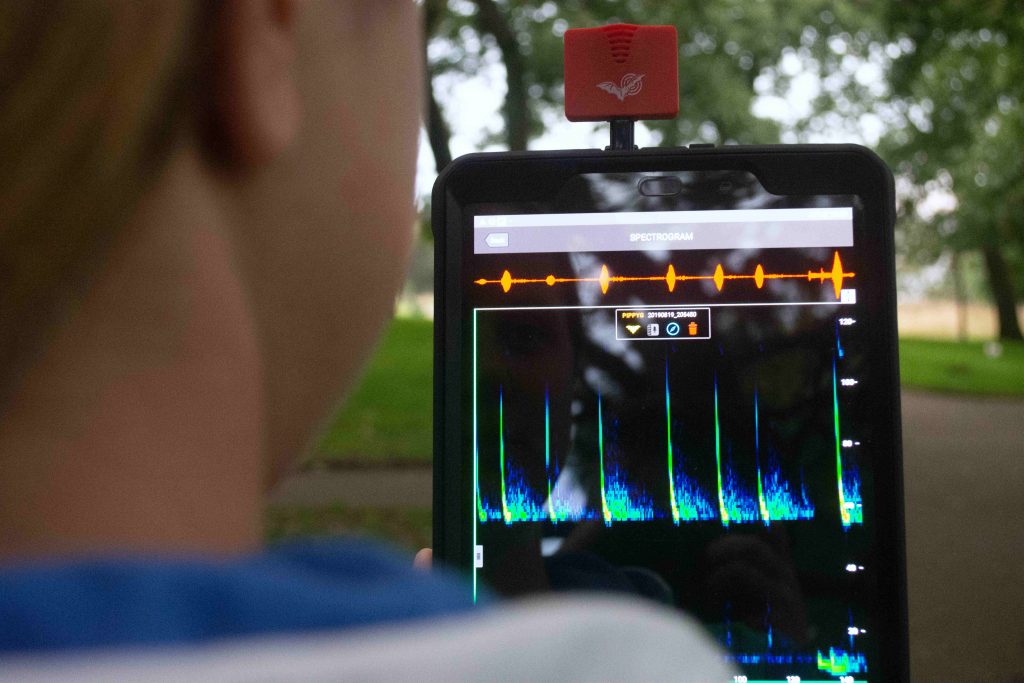

I also support people in towns and villages in their efforts to become accredited as a ‘Bat Friendly Community’. For example, after some training and buying of bat detectors, local volunteers have arranged bat walks to introduce people to the world of bats.

Managing our website www.devonbatproject.org along with social media allows us to spread the message to a wider audience, and during the summer months, there are plenty of events such as bat walks to introduce people to the magical world of bats.

3. What’s your favourite thing about the Greater Horseshoe Bat?

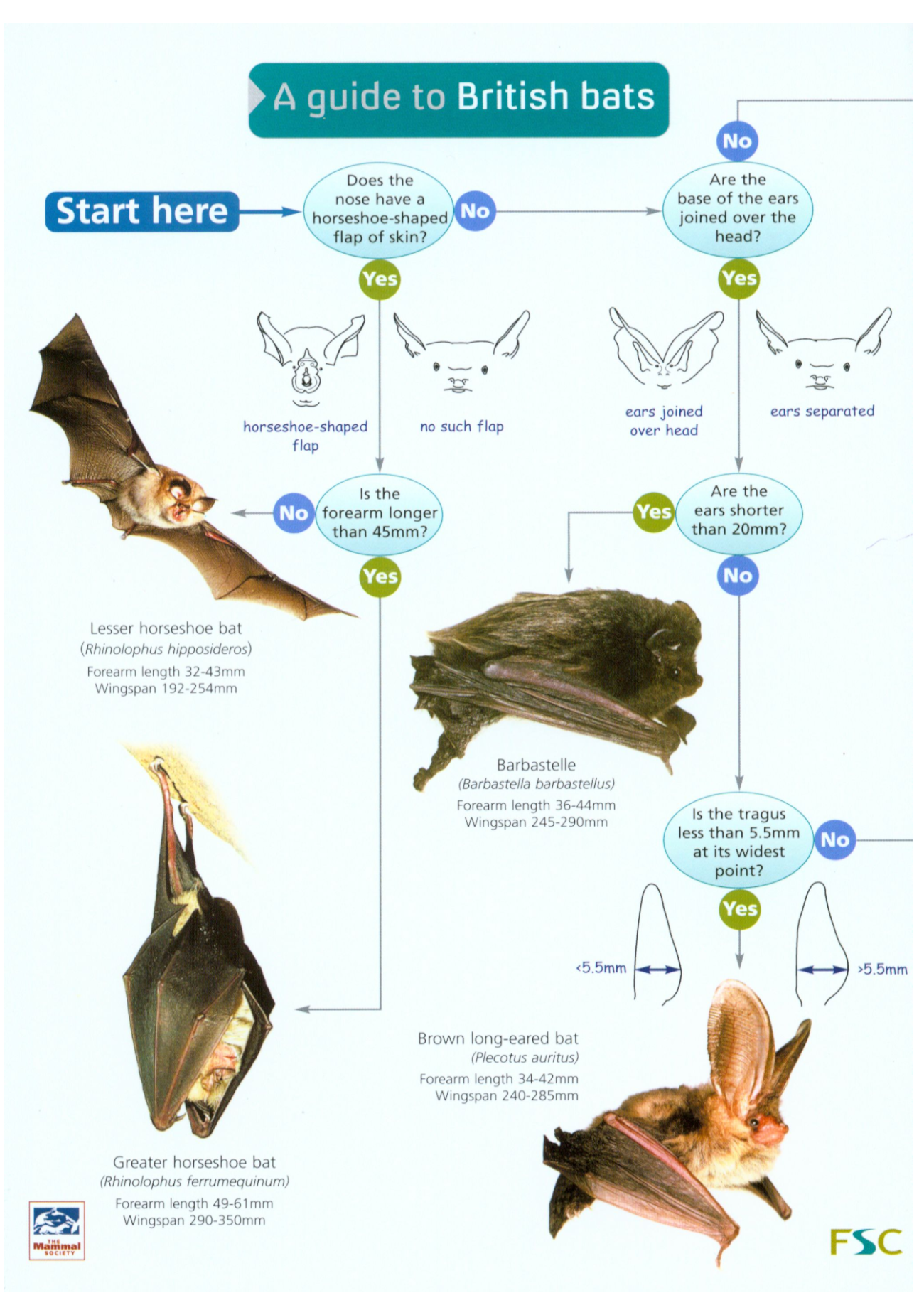

I do love their funny horseshoe-shaped noses, it’s where they get their name from. They use these amazing looking noses for their echolocation – emitting sounds to find their way around in the dark and catch their prey. It’s an amazing technique honed over millions of years of evolution! People are always surprised and intrigued when they see images of this bat and hear their echolocating sounds.

4. Can you tell us why the project focuses on the Greater Horseshoe Bat in particular?

Greater Horseshoe Bats are an important indicator of great habitats; if they are present in an area you know that the surrounding habitats will be good, not just for bats but other wildlife too. However, their numbers have gone down by 90% in the last 100 years, and they remain under threat from habitat loss and declining insect numbers. Therefore if we can improve things for Greater Horseshoes, over time the whole biodiversity of an area will increase.

5. There are many ways to survey bats, what techniques and technology do you use for the project?

Devon Bat Survey is our Citizen Science project involving hundreds of volunteers each year – we use 20 SM4 Bat detectors for this to get as wide a coverage as we can across the county. People borrow the equipment for 3 nights; as well as collecting valuable data on Greater Horseshoe, all other bats are recorded too. Once the data has been returned and run through specialist software, reports are produced. Anabat Express detectors are also used to survey the land of some of the farmers we work with.

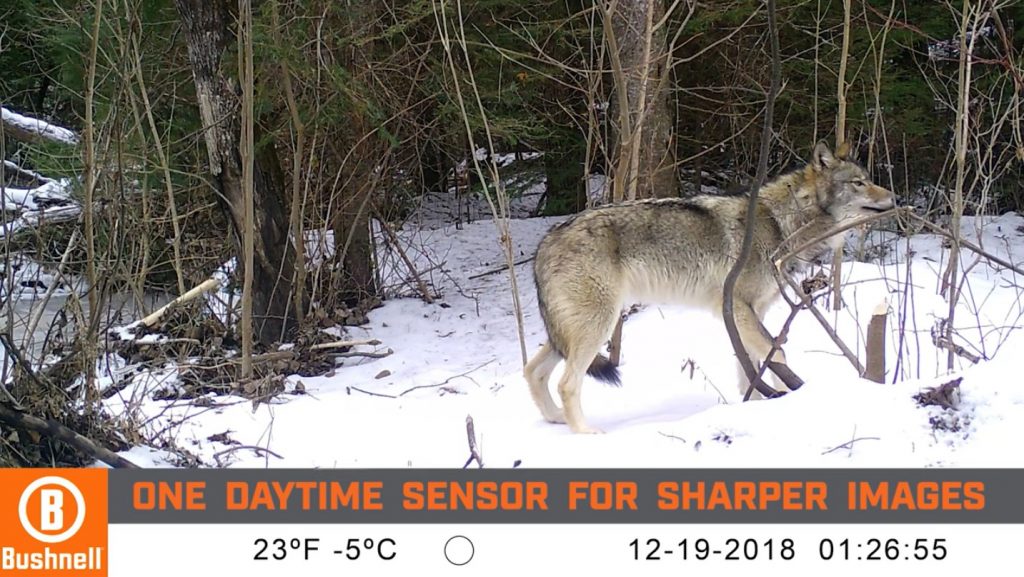

We have placed an infrared camera in one of the roosts – this is fascinating to watch during the breeding season. On bat walks, we use the Magenta 5 handheld detectors so people can hear the bats, along with the Echo Meter Touch detector so we can record and identify what we find.

6. How is the data that is collected used?

The data is sent to Devon Biodiversity Records Centre. From there it can be used by local authorities, conservation bodies, developers and communities to enable them to make informed decisions that might impact on bats. In addition, we have had a University student use the data to undertake habitat modelling to better understand landscape use by Greater Horseshoe Bats.

7. At this year’s National Bat Conference, there was talk of potentially using trail cameras to survey the emergence of bats from their roosts. If the right technology exists, do you think the Devon Greater Horseshoe Bat project could make use of it?

As we are in the final year of our project, we won’t have the time or funding to take advantage of this, but I think trail cameras sound like a great idea for any future projects like ours. Advances in technology will always be useful in bat conservation. As the Echo Meter Touch or similar technology becomes more affordable in future, I often imagine how amazing it would be to see everyone using their smartphones to gather and upload bat data – the ultimate citizen science project!

8. How can readers get involved with the Devon Greater Horseshoe Bat project?

- Look out for Devon Bat Survey which starts again in April 2020

- Do some bat friendly gardening – even the smallest garden can be a home for insects – great food for bats

- If you have a piece of land (large or small) you could use our Management Guides to improve it for bats

- Keep an eye on our website for any events with us or our partners –especially September 2020 which will be our busiest month of events ever with around 30 events for our final Bat Festival.

9. What trends are being suggested by the project – how is the Greater Horseshoe Bat doing?

It’s too early to say as a lot more detailed analysis will need to be done, and the measures put in place by towns, villages and individual landowners will take time to show an effect. The Devon Bat Survey will not really show population changes but can indicate changes in distribution. Work being undertaken by the Bat Conservation Trust will allow us to see the changes over time of the work that we have done. However the general consensus is that populations are stabilising and starting to increase, but I don’t think we can be complacent as the loss of one maternity roost could have a dramatic effect on the population numbers.

10. What is being done to support the population in the future?

Throughout the project, the team has aimed to spread the word about these amazing little creatures and to encourage good habitat management for bats. We hope that once the project comes to an end that the people who share their spaces with these bats will care for them in the future, with a realisation that all species will benefit from actions to improve biodiversity across Devon, including humans!

Marjorie Blamey 1918 – 2019

Marjorie Blamey 1918 – 2019 Marjorie Blamey, who died in September, aged 101, will be well-known to many as the artist of distinguished botanical field guides. Her paintings of wild flowers, trees and ferns are not only scientifically accurate but a joy to see in their fresh colours and lifelike arrangements. Her main aim, she once said, was to make plants look alive, and she achieved it by painting freshly gathered specimens, not, as many botanical artists did, by trying to breathe life into pressed ones.

Marjorie Blamey, who died in September, aged 101, will be well-known to many as the artist of distinguished botanical field guides. Her paintings of wild flowers, trees and ferns are not only scientifically accurate but a joy to see in their fresh colours and lifelike arrangements. Her main aim, she once said, was to make plants look alive, and she achieved it by painting freshly gathered specimens, not, as many botanical artists did, by trying to breathe life into pressed ones. Locating and painting around 2,000 different species for each field guide was quite a task. Marjorie and her husband Philip used to tour Europe in a motorised caravan, getting up at dawn to begin painting specimens gathered the previous afternoon, kept fresh in boxes lined with damp paper (at home she used the fridge or even the bath). In her prime she could get through a dozen watercolour paintings by lunch. Few botanical artists have worked so fast, and yet maintained such consistent quality.

Locating and painting around 2,000 different species for each field guide was quite a task. Marjorie and her husband Philip used to tour Europe in a motorised caravan, getting up at dawn to begin painting specimens gathered the previous afternoon, kept fresh in boxes lined with damp paper (at home she used the fridge or even the bath). In her prime she could get through a dozen watercolour paintings by lunch. Few botanical artists have worked so fast, and yet maintained such consistent quality. Her big break was the Collins Guide to Wild Flowers of Britain and Northern Europe (1974) – known as ‘Fitter and Blamey’ – which was translated into many European languages and sold a million copies. It was followed by field guides to alpine flowers and Mediterranean flowers, vital identification guides to green tours ever since, and the large-format Illustrated Flora of Britain and Northern Europe (1989) which she wrote with her friend and mentor Christopher Grey-Wilson, and considered her best work. Her last field guide was the ambitious Wild Flowers of Britain and Ireland (2003) – or ‘Fitter, Fitter and Blamey’ – whose 4,000-odd colour illustrations she completed at the age of 85 (adding yet more paintings to the revised edition ten years later).

Her big break was the Collins Guide to Wild Flowers of Britain and Northern Europe (1974) – known as ‘Fitter and Blamey’ – which was translated into many European languages and sold a million copies. It was followed by field guides to alpine flowers and Mediterranean flowers, vital identification guides to green tours ever since, and the large-format Illustrated Flora of Britain and Northern Europe (1989) which she wrote with her friend and mentor Christopher Grey-Wilson, and considered her best work. Her last field guide was the ambitious Wild Flowers of Britain and Ireland (2003) – or ‘Fitter, Fitter and Blamey’ – whose 4,000-odd colour illustrations she completed at the age of 85 (adding yet more paintings to the revised edition ten years later). Despite her extraordinary output, Marjorie came to botanical painting surprisingly late. Although she had shown obvious talent in her youth – where she also became an accomplished actress, photographer and, after the outbreak of the Second World War, nurse and ambulance driver – she had largely given up painting to run a dairy farm in Cornwall with her husband, by whom she had four children. She was in her 40s when she began to paint local wild flowers. A friend persuaded her to exhibit, and one thing led to another: a book of magnolias, followed by the first of her field guides.

Despite her extraordinary output, Marjorie came to botanical painting surprisingly late. Although she had shown obvious talent in her youth – where she also became an accomplished actress, photographer and, after the outbreak of the Second World War, nurse and ambulance driver – she had largely given up painting to run a dairy farm in Cornwall with her husband, by whom she had four children. She was in her 40s when she began to paint local wild flowers. A friend persuaded her to exhibit, and one thing led to another: a book of magnolias, followed by the first of her field guides. Marjorie Blamey was modest about her talent. She seems to have loved the life of botanical travel, working all hours to complete her assignments. When you consider that the latest Collins Flower Guide took four artists a number of years to complete, and it took Keble Martin a whole lifetime to finish The Concise British Flora, her total of around 12,000 flower paintings for five major field guides, plus other work, begun in her 50s and ending in her 90s, is a record that will, I suspect, never be exceeded.

Marjorie Blamey was modest about her talent. She seems to have loved the life of botanical travel, working all hours to complete her assignments. When you consider that the latest Collins Flower Guide took four artists a number of years to complete, and it took Keble Martin a whole lifetime to finish The Concise British Flora, her total of around 12,000 flower paintings for five major field guides, plus other work, begun in her 50s and ending in her 90s, is a record that will, I suspect, never be exceeded.