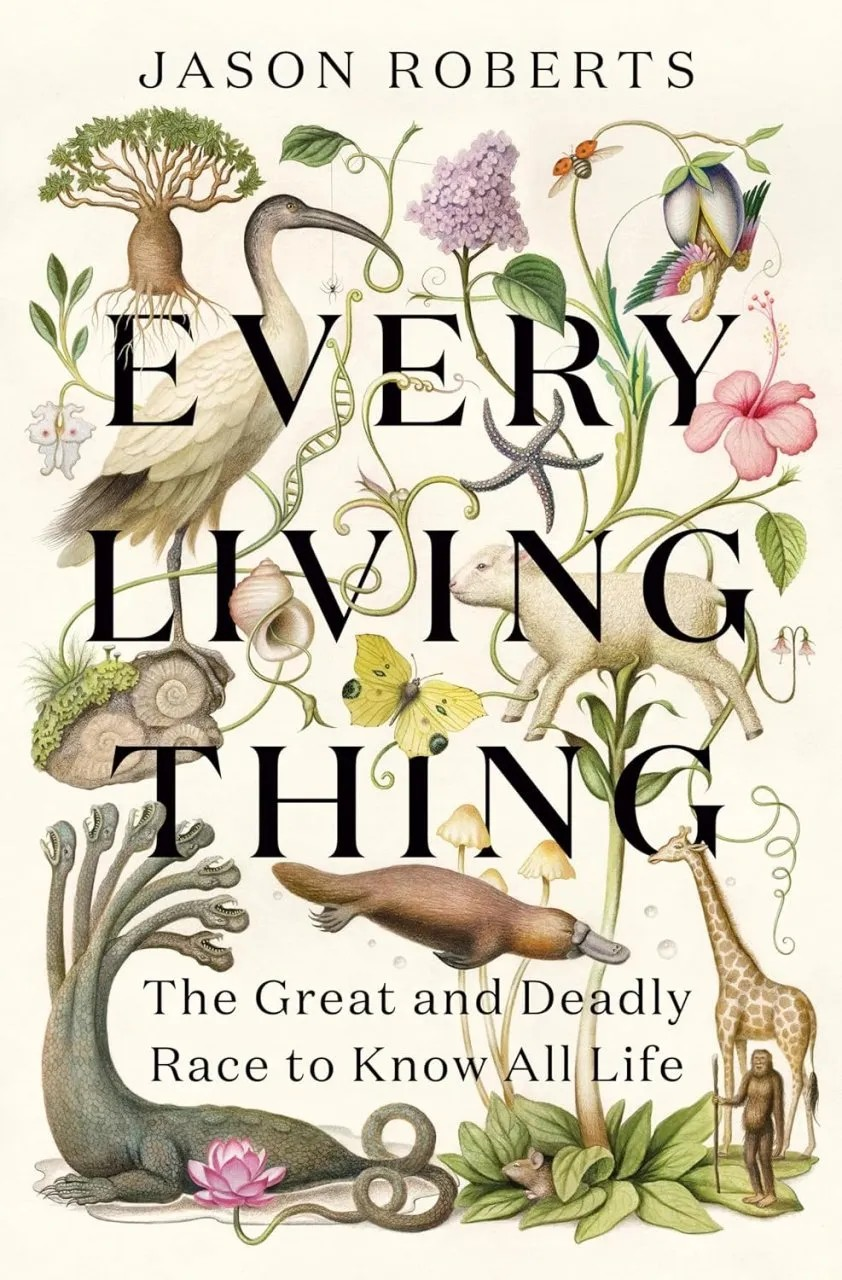

***** An epic history of taxonomy across three centuries

***** An epic history of taxonomy across three centuries

Linnaeus was not the only seventeenth-century scholar trying to get to grips with life’s diversity; French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (Buffon hereafter) was another. Though the two men never met, their ideas did. Author Jason Roberts provides a biography of Linnaeus and Buffon, writing an epic history of their work and intellectual legacy. It has quickly become one of my favourite books this year for introducing me to a new scientific hero.

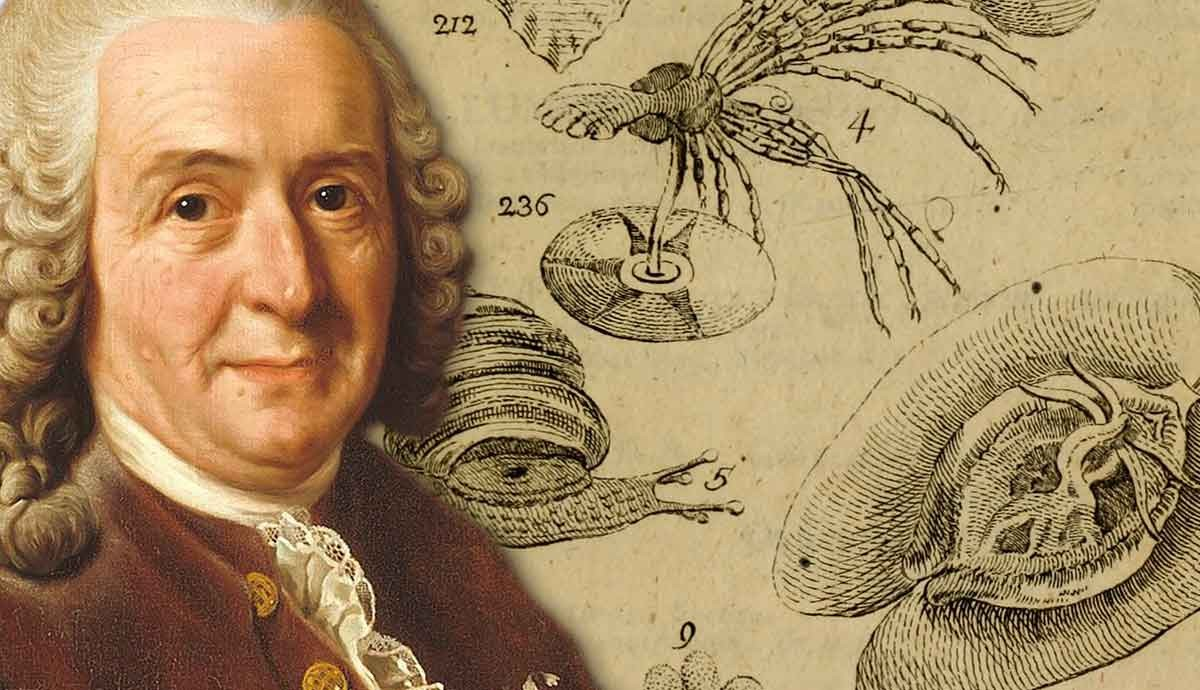

In the first two parts, Roberts charts the lives and works of Linnaeus and Buffon, alternating between the two as he goes. Having just reviewed The Man Who Organized Nature, I could not resist immediately checking his reference section. Broberg’s books is not amongst them, though he has consulted several other biographies Broberg recommended. His coverage of Linnaeus follows the major beats of his life but leaves out much of the extraneous details that Broberg provided, focusing on his taxonomical ideas. It quickly becomes apparent that Broberg was respectful, even mild, just reporting the facts of Linnaeus’s life but rarely passing judgment. Roberts has no such reservations, calling him out for his arrogance and immodesty. He also covers Linnaeus’s apostles who were sent on collecting expeditions to uncharted parts of the world with often fatal outcomes. True, they went willingly and were not the only ones to do so at the time, but they provided a number of harsh lessons. Roberts particularly holds Linnaeus’s feet to the fire regarding his scientific racism. “Later apologists have attempted to absolve Linnaeus of racism” (p. 180), but not Roberts. Sure, others would make the message more explicit and amplify it but modern race science “has a genealogy that can be traced directly to the pages of Systema Naturae” (p. 181).

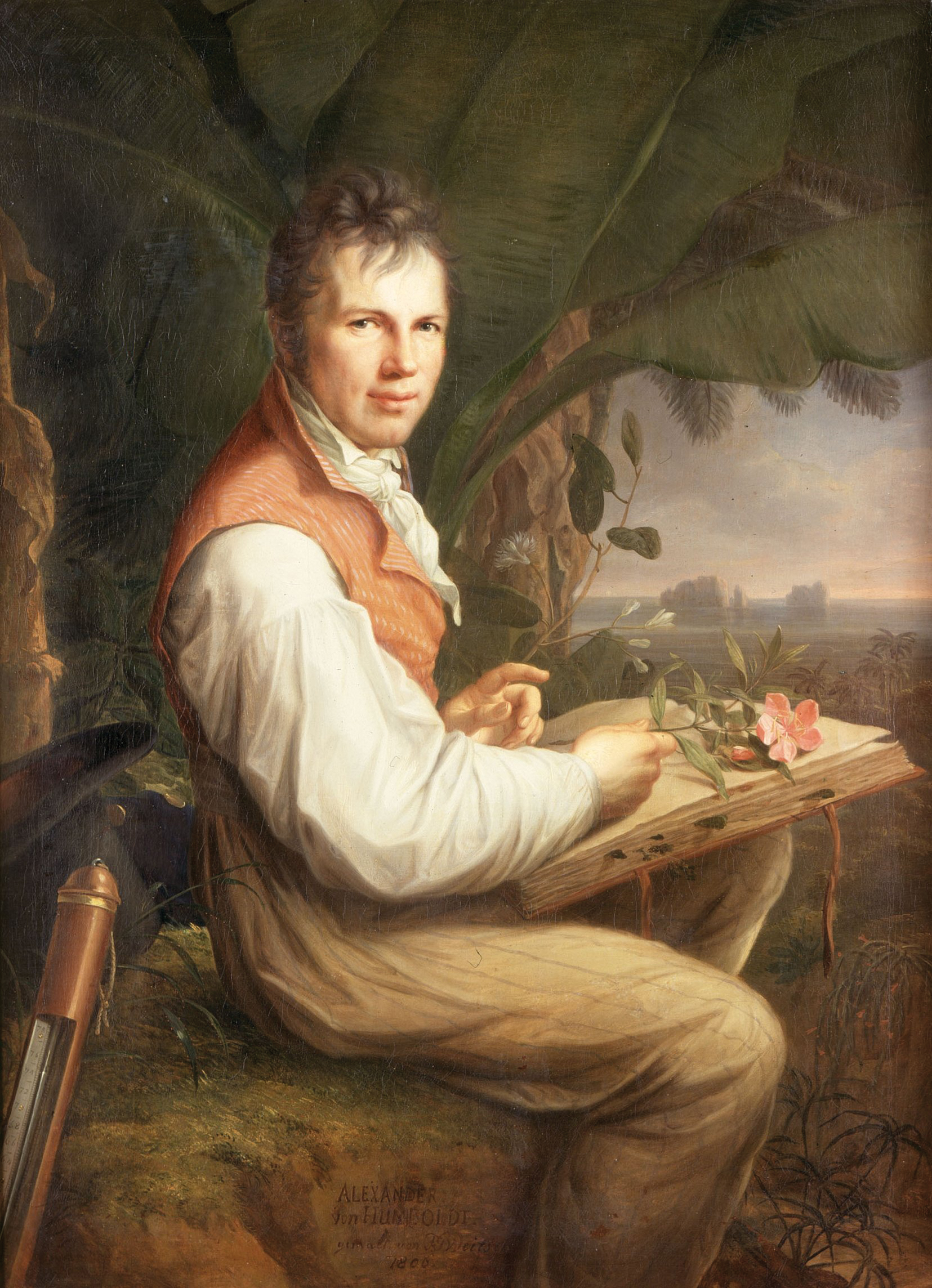

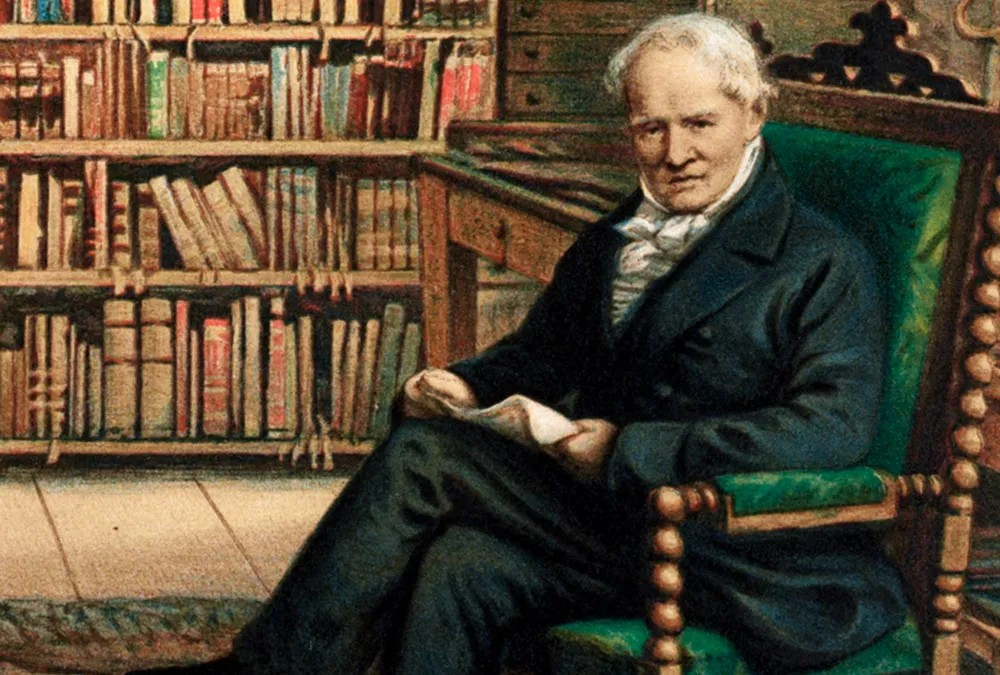

In contrast, Buffon (1707–1788) emerges from this book in a far more positive light. Inheriting a fortune at age 10, by 1739 he was nominated as intendant of the Jardin du Roi, gaining both the ear and the financial support of King Louis XV. That was vital for the project that would dominate the rest of his life: Histoire Naturelle. Intended as an encyclopedia of all creation, he wrote 36 large and painstakingly detailed volumes, covering the mineral kingdom and part of the animal kingdom. Like Linnaeus, Buffon was a polymath and became captivated by life’s diversity, but that is where the resemblances end. I admit to knowing little about him before reading this book, but he was a fascinating character! He was the morally more upstanding person of the two, vocally opposing slavery and treating the women who crossed his path as equals. At home, “Buffon designed a life of maximum efficiency” (p. 64), having his valet wake him up at 5 AM every day (even if it meant being dragged out of bed) for a strictly scheduled day of writing in his spartan room, with breaks for meals and some socializing. It was a lifestyle he would stick to for the next 50(!) years, delighting in his “rigorous cultivation of solitary focus” (p. 66).

Who Was Carl Linnaeus? via The Collector.

Who Was Carl Linnaeus? via The Collector.

As if that quirk was not enough to endear Buffon to me, his thinking was decades if not centuries ahead of his time. In his writings, he speculated about extinction, common descent and the evolution of species, the cellular basis of life, the finitude of natural resources, and an impending epoch of humans. Roberts provides relevant context to explain the rhetorical safeguards Buffon employed to sidestep censors and is careful to avoid grand claims: we should be careful not to retrofit today’s knowledge to his hunches and speculation back then. He also disentangles the “thicket of significant linguistic differences between Buffon’s era and ours” (p. 199), pointing out that e.g. evolution as we understand it had not yet been coined. Even so, Darwin admitted that Buffon’s ideas were “laughably like mine” (p. xi).

Of relevance to the history of taxonomy, and the leitmotif of this book, is the rivalry between the ideas of these two men. Roberts captures the contrast beautifully early on: “To Linnaeus’s mind, nature was a noun. All species remained as created during Genesis, representing an unchanging tableau. To Buffon, nature was a verb, a swirl of constant change” (p. 7). Linnaeus, like most naturalists at the time, believed in the fixity of species; evolution and extinction implied that Creation was imperfect. Buffon believed that species evolved and went extinct, even if he did not yet know how. Their differences reflected a deep philosophical divide. Linnaeus believed in absolute universal truths, in Aristotelian essences, with species being real entities. Buffon, in contrast, considered systematics and species useful concepts but also flawed human constructs.

What elevated the book for me is that Roberts leaves himself a comfortable 110 pages in part 3 to describe what happened next and what the relevance of their ideas is to us today. The grand arc that he traces is that, after his death, Buffon’s ideas were quickly sidelined by Linnaeus’s adherents but over time have regained their significance. He takes you through the French Revolution and its aftermath, giving terribly interesting profiles of famous naturalists who embraced Buffon’s ideas to various degrees. He also discusses Britain’s lukewarm reception and then slow acceptance of Linnaeus’s ideas, with his collections ending up in England and leading to the founding of the Linnean Society of London. Simultaneously, Buffon influenced Darwin, Thomas Henry Huxley, and his grandson Julian Huxley who lived through the rise of genetics.

Today, Linnaeus’s taxonomical hierarchy has started to creak under the sheer magnitude of the planet’s biodiversity and has increasingly been abandoned, leaving just binomial nomenclature and a hierarchy of categorical ranks. Buffon’s observation, that life is like a web or network instead of a thread, seems more relevant than ever. Meanwhile, species concepts remain troublesome beasts, and some scholars propose we consider species “snapshots rather than static points”, which hews closer to Buffon’s idea they are “an entity of reason rather than a physical fact” (p. 352).

Though Roberts is not a science historian, he has done his homework, going back to source material wherever possible. He is not shy to judge both men by modern standards with Buffon emerging as the clear moral victor. He leaves ample space to discuss the aftermath and modern relevance of their ideas, which is a welcome stroke of brilliance. If you are new to the history of taxonomy, I have no hesitation in recommending that you start here; Broberg’s book is a more advanced text on a more circumscribed topic that will make for good follow-up reading.

Flemming Ulf-Hansen is an ecologist with nearly 37 years of experience working in wildlife conservation, primarily across Exmoor and Salisbury Plain. He is the founding chair of the Exmoor Mires Project and specializes in ecological restoration, with a host of expertise in grassland, woodland, and heathland management, as well as invasive species control. He joined the Nature Conservancy Council in 1988 and was awarded a Churchill Fellowship in 2010 to study habitat restoration.

Flemming Ulf-Hansen is an ecologist with nearly 37 years of experience working in wildlife conservation, primarily across Exmoor and Salisbury Plain. He is the founding chair of the Exmoor Mires Project and specializes in ecological restoration, with a host of expertise in grassland, woodland, and heathland management, as well as invasive species control. He joined the Nature Conservancy Council in 1988 and was awarded a Churchill Fellowship in 2010 to study habitat restoration.