Placed on the IUCN Red List in 2021, Swifts are now recognised as one of Britain’s most endangered bird species, having suffered a staggering population decline of around 60% in just 25 years. These incredible birds return to the same nesting site each year after migrating from a summer in Africa, however due to urban development and land use changes, their natural nesting sites are rapidly disappearing, which is accelerating their already concerning population decline.

In 2024, over 40 residents of two neighbouring streets in Swinton, Salford decided to take action and create their own ‘Swift Street.’ This community-led project saw the creation and installation of over 100 specialist nest boxes, providing essential nesting spaces for their local swift colony. The Swift Street initiative is part of a wider effort to transform Manchester into a Swift City and ensure the long-term survival of these endangered birds.

In this blog, resident Suzanne Pendleton and RSPB Community Engagement Officer Roshni Parmar-Hill tell us about their journey to create the largest Swift Street in the north-west of England.

My Swift Street Experience – Suzanne Pendleton

My name is Suzanne Pendleton, and I am a mum to two girls, Molly and Tess. I have lived in Houghton Lane in Swinton, Salford with them and my hubby for 30 years, and have been involved in the Greater Manchester Swift Street initiative since August 2024.

During lockdown, I started to value spending more and more time in our little garden as so many people did, and whilst I was outside, I spotted a number of birds zooming around, screaming and flying over our house. At first I wasn’t quite sure what they were, so I asked my friend Kathleen and she enlightened me that they were Swifts! Swifts are migratory birds, so when summer ended they left Swinton and headed back to Africa, but every year I eagerly anticipate their return.

Over time, my understanding of this species grew, and I learnt of their declining population numbers – whilst also developing a stiff neck constantly looking up to the sky to watch their incredible manoeuvres! I am privileged to live in a friendly community on Houghton Lane, so I messaged our community group and asked if anyone knew about our Swift population, or where they may be nesting. Initially we were unsuccessful in locating their nesting sites, however we struck gold in Spring 2024 with the help of the Swift Mapper app and discovered we had four nest sites on Houghton Lane and its surrounding roads.

In this time, I’d also discovered that there was another small colony located less that 1/4 mile away, and a resident of this local road got in touch to tell us that Roshni from the RSPB had been to visit their colony and help establish their Swift Street – she then asked if we would be interested in developing our own Swift Street on Houghton Lane. I think we are so privileged that these incredible urban birds choose to nest on our lane, and as their nesting sites are often threatened by redevelopment, having the means to install boxes provides us with a wonderful opportunity to support them.

This project has been a whole-community effort, superbly guided by the wonderful Roshni. With her incredible support and guidance, we used our community group to share the news of the development and launch of our own Swift Street, and we were overwhelmed by the local response. So many families were keen to support our Swift population, and we received requests for over 80 boxes. In January, we were blessed with some bright days, which allowed us to visit each home that had requested a Swift box and advise the families in selecting a suitable aspect and position for their box. As we chatted to more residents about the project I grew in confidence talking about Swifts, and increased my own knowledge too.

Roshni also gathered support from a local college who built our Swift boxes, whilst a local resident, Haldis, made our nest cups. Roshni and several Swift Ambassadors (volunteers who work alongside communities to raise awareness of Swifts and encourage positive action to protect them) then visited our Girl Guiding group to lead some Swift-themed activities which captivated the girls’ interest. They loved learning about the species and contributing to the project by painting our boxes with bird-friendly materials recommended by the RSPB. Saturday 8th March was our first installation day, and local roofer Ryan put up 25 boxes. Since then, we have now installed over 80 along the street, and we are ready for the first wave of our Swift populations to return!

It’s been an absolute honour to be involved in this project, and I feel so lucky that our community can do something practical to support our local Swifts.

RSPB Community Engagement Officer – Roshni Parmar-Hill

I’ve been so privileged to work alongside individuals as passionate and energetic as Suzanne whilst bringing the Swinton Swift Street project to life. This truly is a community endeavour – proving that, to misquote a famous phrase ‘it takes a village to save a Swift’. From Suzanne’s tireless recruitment of her neighbours’ support along her street, and the hard work of her Girl Guide pack painting and waterproofing the nest boxes, to the students of independent skills provider The SkillCentre in Trafford who constructed the boxes, it’s been a joy to see so many people pull together to take positive action for nature.

The screaming calls of migratory Swifts are what first drew Suzanne to this species and fostered her connection. If we want to keep welcoming them back screeching overhead every summer, then they need our help now more than ever to create and protect safe nesting habitats. This incredible species travels a whopping 3400 miles to reach the UK from East Africa every year – crossing 25 countries over the course of 4 weeks in their journey to reach us. Swifts spend most of their time in the air – feeding, sleeping and even mating all whilst in flight! – only landing to nest, which is where Suzanne and her neighbours come in.

Swifts return to the exact same nesting spot every year, but increasingly these nesting sites have been hit by property renovations and the removal of old buildings. This has contributed to a 62% decline in Swift numbers between 1995 and 2020, and the species have now been added to the UK’s Red List of Birds, meaning its amongst our most endangered. However, with the installation of over 80 nest boxes on Suzanne’s street, we intend to grow another new urban Swift colony and build on wider ongoing work to develop Manchester into a Swift City. This project is supported by the expansion of our network of brilliant ‘Swift Champions’ who are leading the development of nesting sites at scale, manufacturing swift boxes and raising people’s awareness and engagement of the project and species through walks, talks and workshops.

As Suzanne and her neighbours now prepare for a special Swift Homecoming Street Party to officially declare it a Swift Street and welcome their bird’s home, all eyes will be fixed on the skies for a glimpse of the street’s feathered residents moving into their new addresses…

If you feel inspired to bring your own community together in support of Swifts, or want to find out more about all things Swift, including Swift Champions, nest boxes and the Swift Mapper app, then head to https://www.rspb.org.uk/whats-happening/news/how-the-species-volunteer-network-is-supporting-volunteers-and-communities-to-help-save-swifts

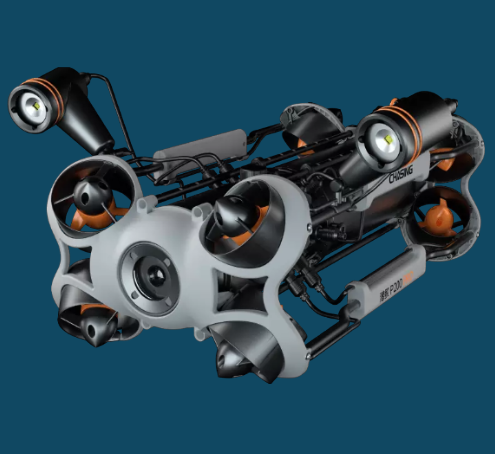

Explore our range of swift boxes here.