Formed in 2010, the core aim of the Devon Badger Group is to protect badgers and their habitats. Funded by membership, donations and fundraising events around Devon, they run a free 24/7 helpline for sick or injured badgers and other badger-related issues.

Formed in 2010, the core aim of the Devon Badger Group is to protect badgers and their habitats. Funded by membership, donations and fundraising events around Devon, they run a free 24/7 helpline for sick or injured badgers and other badger-related issues.

We recently had the opportunity to chat with Jenny Pike, Chair of the Devon Badger Group, about the group’s important work, their successes and challenges, and how Covid-19 has affected their lives over the past year.

Firstly, can you give us a brief introduction to the Devon Badger Group and your role within the group?

My name is Jenny Pike and I am Chair of the Devon Badger Group (DBG). In a nutshell, the purpose of the DBG is to protect badgers and their habitat, record their activity, educate and further the public’s understanding of badgers, and to encourage tolerance, appreciation and respect for all wildlife. We also work with the police and RSPCA, and respond to any activities that could be detrimental to the welfare of badgers.

What do you consider to be the main threats to badgers in the UK?

Sadly there are many threats to badgers and, despite gaining legal protection in 1992, badger persecution is on the increase. In England, one of the biggest threats badgers face is the government licenced badger cull. Since the cull began in England in 2013, a total of 140,991 badgers have been killed, 30,345 of which have been in Devon.

Sadly there are many threats to badgers and, despite gaining legal protection in 1992, badger persecution is on the increase. In England, one of the biggest threats badgers face is the government licenced badger cull. Since the cull began in England in 2013, a total of 140,991 badgers have been killed, 30,345 of which have been in Devon.

Other serious threats are housing developments where, even if setts are protected with appropriate mitigation measures, a significant amount of foraging ground can be lost. New roads can also impact badgers if appropriate badger tunnels are not installed or are installed in the wrong place. Hunts sometimes block badger setts to prevent foxes escaping down them and, as already mentioned, illegal badger persecution is on the rise along with other forms of organised wildlife crime such as dog fighting.

I am sure everyone will have seen many badgers dead on the side of the road. No one knows exactly how many badgers are killed by vehicles each year – one estimate has it at 50,000.

What are your main goals as a group?

Our main aims are to protect badgers, their setts, and their habitats. But we feel that if we can increase the public’s understanding of badgers and dispel some of the myths, people will feel more encouraged to protect them. Sadly, most people we talk to have never seen a live badger. This is why, whenever we are contacted by members of the public who think they have badgers visiting their gardens, we offer to put up a trail camera so they can actually watch visiting badgers go about their business, which is usually looking for earthworms and other invertebrates. This often has a very positive effect and has changed people’s view of badgers.

What would you consider to be your greatest success as a group?

In 2019, through some very generous grants and donations, the DBG was able to fund two members to train to become licenced lay vaccinators. I was lucky enough to be one of them. Since then, we have worked in collaboration with the Somerset Badger Group to vaccinate badgers in Devon and Somerset, which has allowed us to gain valuable experience. We hope this will continue and expand in the future.

In 2019, through some very generous grants and donations, the DBG was able to fund two members to train to become licenced lay vaccinators. I was lucky enough to be one of them. Since then, we have worked in collaboration with the Somerset Badger Group to vaccinate badgers in Devon and Somerset, which has allowed us to gain valuable experience. We hope this will continue and expand in the future.

Covid-19 has caused difficulties and presented issues for all of us. How has the pandemic affected the work that the DBG does, and have there been any unforeseen positive effects?

On the positive side, it is possible that less cars on the road in the first lockdown resulted in fewer badgers being killed or injured. Spring is when cubs are still dependent on their mums and when most road casualties occur, and so this would have had a significant effect on badger cub survival rates if mum survived to successfully wean them.

On the negative side, although we were given permission by Devon and Cornwall Police to continue to rescue injured badgers on animal welfare grounds, we were not able to carry out sett surveys, monitor setts which had been targeted previously, or visit homeowners who had contacted us for advice on badger issues. We were also unable to carry out our regular fundraising activities which, in normal circumstances, not only provides much needed funds, but also gives us an important opportunity to engage with the public and answer their questions. This is something I personally have missed a great deal as there is no substitute for face-to-face communication.

Having said that, we have been able to continue our most important work by keeping in regular contact with our committee and members through electronic communication, Zoom and Teams meetings. This has had an unexpected benefit of not only reducing our carbon footprint, but also allowing us to engage with our members across the whole of the county (internet permitting!).

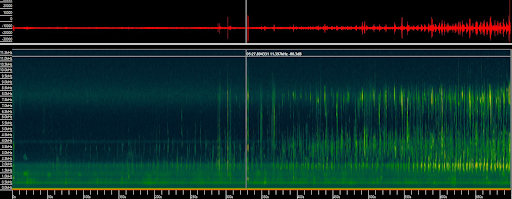

You mention that you sometimes use trail cameras in some of your work – could you tell us a bit more about this?

We use trail cameras extensively in the DBG and they have been invaluable in proving setts are active in cases of sett disturbance and sett blocking. They have also been used to great effect when showing school children the wonders of a shy nocturnal animal they would never usually see. I have been using a number of cameras recently on a beaver enclosure to ensure the badgers and other wildlife are able to move freely in and out (except the beavers of course!). I also have my own trail camera and I still maintain that it was the best Christmas present ever. I use it all the time for monitoring the wildlife in my own garden in Plymouth.

In May of last year, the government announced that they hope to shift away from culling and towards badger vaccination to help in the fight to eradicate bovine tuberculosis (bTB) in England. What does this mean for the group and will the DBG be involved with badger vaccination programmes?

The Devon Badger Group is opposed to the badger culls but, of course, recognises the distress and hardship bTB causes for farmers, their families and their animals. We sincerely hope that the government honours its commitment to progressing a vaccine which is much more likely to provide real benefits to farmers and their cattle than the current bTB strategy.

Controlling the spread of bTB is a complex issue that will need a raft of measures to tackle, but they must all be backed up by sound scientific evidence. The role badgers play in bTB transmission is still not fully understood: what limited studies have been carried out to determine the prevalence of bTB in badgers have concluded that approximately 4.5% of badgers tested are infected with bTB. It is now accepted that the vast majority of bTB transmission to cattle is from other cattle, but this was previously unclear due to the poor accuracy of the routinely used skin test. This skin test has been found to be around 50-80% accurate, resulting in up to 1 in 5 infected cattle remaining undetected in the herd to pass on the infection.

With this in mind, and the fact that bTB can live in soil and slurry for many months, there is enough doubt on the role badgers play in disease transmission to compel the government to re-evaluate their bTB strategy for the benefit of farmers and the whole farming industry.

We welcome the government’s commitment to replace badger culling with the more humane badger vaccination and we hope to be involved in any future badger vaccination initiatives. We would be very happy to work with and support Defra and other organisations in delivering on this new initiative until a more effective cattle vaccine can be deployed.

It is obvious that you are very passionate about badgers and love them dearly. What is your favourite fact about badgers?

As large as they are, their main food source is earthworms and they have to delicately pull them out of the ground without snapping them!

How can people help protect badgers and get involved in their local area?

Please keep an eye on your local area, especially if you have any setts near you. If you would like help on identifying signs of badgers, we would be more than happy to help (Covid-19 permitting).

Report any suspicious activity around badger setts to the police and do also let us know. Please also report dead badgers to us – in spring this is important if it is a lactating female with dependent cubs below ground.

Please consider joining the Devon Badger Group. We are a small but active group but have one of the largest and most rural counties in England to cover.

We can be contacted at devonbadgergroup@gmail.com and on our 24/7 helpline number 07710 971988 or I can be contacted direct on 07791 490572.

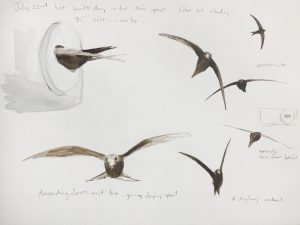

A summer visitor, the common swift appears suddenly with the change in season, swooping overhead with its unmistakeable call. From their travels to Africa, to their short breeding season in the UK, swifts appear to defy gravity with their extraordinary migratory feats, with some in flight for ten months of the year. In

A summer visitor, the common swift appears suddenly with the change in season, swooping overhead with its unmistakeable call. From their travels to Africa, to their short breeding season in the UK, swifts appear to defy gravity with their extraordinary migratory feats, with some in flight for ten months of the year. In

From the Sunday Times bestselling author of

From the Sunday Times bestselling author of