Moths are a fascinating and beautiful part of the natural landscape in the UK. However due in part to their elusive nature, often plain colouration and the unfavourable habits of a few cloth eating species, they very rarely receive the same recognition as their more illustrious butterfly cousins.

However, understanding and protecting our moths is more important now than ever. Recent studies in the UK have highlighted that many common and specialist moth species are continuing along a worrying trend of decline as they are subject to increasing pressures from urbanisation, pollution, agricultural intensification and climate change. The latest State of Moths Report estimated declines in moth abundance of around 33% between 1968 and 2021, while the latest State of Nature report estimates declines for many common moths of around 25% between 1978 and 2018. While the estimated rate of decline does vary between studies, being influenced by the timescale over which data was collected and the geographic location data was collected from (northern counties appear to undergo slower declines in moth abundance than southern counties), they come to the same conclusion that many of the UK’s moths are declining at significant rates.

These reports would not be possible without the extensive records provided by professional entomologists and amateur moth enthusiasts around the country. You can help conserve this key group by submitting your own records to either a local record centre or to a national recording scheme, such as the National Moth Recording Scheme (NMRS).

Identifying Moths

Getting started with identifying moths can appear a rather daunting task. This concern is understandable as a quick skim through any field guide will quickly show the near identical appearances of some species and the extreme variation present in others. However there are a number of moth species that are quite distinct and offer an excellent introduction to the world of moths.

In this article we have compiled a list of those species which can be encountered throughout most of the UK. Some species are more restricted than others and some are only typically encountered when using a light trap, however they are all fantastic species to become familiar with.

Silver-Y

Latin name: Autographa gamma

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Medium

Look out for: Unbroken silver “y” on the upper forewing.

Did you know?: The Silver-Y undertake intergenerational migrations. Immigrant moths in spring will breed and over successive generations swell their population size by around four times, until the Autumn when they emigrate back across the channel and south through Europe.

Large Yellow Underwing

Latin name: Noctua pronuba

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Medium/Large

Identification: Yellow hindwings with black borders are the best indicator, however it often rests with wings closed and has a highly variable appearance.

Did you know?: Considered by some to be one of our most common medium-large moths, especially when populations are bolstered by occasional large immigrations in the south of the UK.

Red Underwing

Latin name: Catocala nupta

Distribution: Throughout UK, most common in south-central England

Size: Large

Identification: Red hindwing is very distinctive. Similar looking species have a darker crimson red and are much scarcer.

Did you know?: The Red Underwing is gradually increasing its range northwards and becoming more common in previously low-density colder regions.

Angle Shades

Latin name: Phlogophora meticulosa

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Medium

Identification: Unique folded wings give the impression of a fallen autumn leaf

Did you know?: Adult moths are often encountered in the day resting in the open.

Peppered Moth

Latin name: Biston betularia

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Large

Identification: Rests with wings spread open. White form is peppered with black spots. Black form has mostly uniform colour and is generally only found in urban areas.

Did you know?: The abundance of white and black variants of the Peppered Moth has been extensively studied and is often used as an example of evolution by natural selection.

White Ermine

Latin name: Spilosoma lubricipeda

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Medium

Identification: Strong white coloured forewings, peppered with black spots, and a yellow-coloured upper abdomen. Wing colour and spotting is variable within and between populations.

Did you know?: Its common name is derived from its resemblance to an Ermine coat.

Muslin Moth

Latin name: Diaphora mendica

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Medium

Identification: They have large stocky wings. Males typically have grey-brown coloured wings, whereas Females have a similar colouration to White Ermine moths, though their wings are opaque

Did you know?: Male Muslin Moths in Ireland have a creamy white colouration to their wings. Similarly coloured males can also be found in some locations on the Cornish/Devon border.

Swallow-tailed Moth

Latin name: Ourapteryx sambucaria

Distribution: Throughout UK, though scarcer in Northern Scotland

Size: Large

Identification: Broad wings with a pale uniform yellow colour, intersected by diagonal dark lines. Hindwings have short tails.

Did you know?: The species is hard to encounter without a light trap. The adults have a short flight period and are strictly nocturnal, while the caterpillars have a cryptic colouration which gives them the appearance of a twig.

Feathered Thorn

Latin name: Colotois pennaria

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Medium

Identification: Rests with wings flat apart. Wings are a reddish brown with a pink hue and have a slightly hooked tip on the forewing. They fly very late in the year which can help with distinguishing from similar species.

Did you know?: Their common name is derived from the large feathered antenna present on males of the species.

Hebrew Character

Latin name: Orthosia gothica

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Medium

Identification: Have distinctive and unique black markings on the forewing.

Did you know?: Their common name is derived from the markings on the forewing which resemble the Hebrew letter Nun.

Common Quaker

Latin name: Orthosia cerasi

Distribution: Throughout UK, though scarcer in Northern Scotland

Size: Medium

Identification: Has a highly variable markings and colouration, however the strong outline of the “oval” and “kidney” markings on the forewings is a helpful identifier.

Did you know?: The four quaker species in the UK are believed to have received their common name back in the 1700s. Lepidopterists took inspiration from the Quakers at the time, who apparently wore clothing of similar hues.

Elephant Hawk-Moth

Latin name: Deilephila elpenor

Distribution: Throughout UK, though scarce in Scotland

Size: Large

Identification: Has striking and well defined pink colouration across the whole body.

Did you know?: The name of the Elephant Hawk Moth is derived from its resemblance to an Elephant’s trunk when in its larval form.

Poplar Hawk-moth

Latin name: Laothoe populi

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Large

Identification: Unique wing shape where hindwings extend beyond forewings and gives it a resemblance to a dead leaf. Its abdomen is curved upwards at the tip.

Did you know?: This is believed to be our most common Hawk-Moth species and it can be found by light trapping in summer throughout the UK.

Jersey Tiger Moth

Latin name: Euplagia quadripunctaria

Distribution: Mostly found it the South-west of the UK, though it is spreading North

Size: Medium-Large

Identification: Wings bear a unique diagonal zebra stripe pattern which can be used to tell it apart from other Tiger Moth species.

Did you know?: Until recently this moth was considered scarce in the UK and could only be commonly encountered on Jersey and some parts of the South Devon coastline.

Garden Tiger Moth

Latin name: Arctia caja

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Medium-Large

Identification: Bright orange hindwings have bold blue-black spots which can help tell this species apart from other Tiger Moths

Did you know?: The Garden Tiger has defensive glands behind its head which it uses to secrete a toxic fluid when attacked.

Scarlet Tiger Moth

Latin name: Callimorpha dominula

Distribution: Mostly found it the South-West of the UK and Wales

Size: Medium

Identification: The forewings have a distinct metallic green-black colour patterned with white/cream coloured spots. Hindwings are a striking red colour in most individuals.

Did you know?: Rarely aberrant forms of Scarlet Tiger Moth occur with yellow underwings.

Six-spot Burnet

Latin name: Zygaena filipendulae

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Medium

Identification: Has metallic coloured forewings patterned with three pairs of vibrant red spots

Did you know?: The six-spot Burnet is the commonest burnet moth in the UK and can be found across most of the country, including the outer hebrides.

Cinnabar Moth

Latin name: Tyria jacobaeae

Distribution: Throughout UK

Size: Medium

Identification: Forewings are dark black with a long streak of vibrant red on the outer edge. Antennae are thin and lack the bulbous tip of similar looking Burnet moths.

Did you know?: The caterpillars are gregarious feeders of ragwort, and have been intentionally introduced into the United States, Australia and New Zealand to biologically control ragwort.

Common Plume

Latin name: Emmelina monodactyla

Distribution: Common in England with increasing scarcity further North

Size: Small

Identification: This rather bizarre looking moth rests with the wings held away from the body, giving it a unique T shape.

Did you know?: These moths have clefts in their wings and plumes at the end of each division of the wing.

Suggested reading:

Field Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland

Field Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland

Paperback | October 2018

The third edition of the Field Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland has been fully revised, updated and restructured, bringing it in line with the latest thinking in taxonomy.

Field Guide to the Micro-moths of Great Britain and Ireland Paperback | December 2023

The fully revised and expanded second edition of the ground-breaking book. This is a complete guide to the Micro-moth families found in the UK. The second edition covers over 1,300 species with more than 1,500 detailed photographs and artworks.

British Moths: A Gateway Guide

British Moths: A Gateway Guide

Spiralbound | September 2021

British Moths: A Gateway Guide is a wonderful introduction to 350 species of the most common and eye-catching adult moths that you may encounter in the UK. Species are organised by season, and similar-looking moths are placed alongside one another for ease of identification.

Atlas of Britain & Ireland’s Larger Moths

Atlas of Britain & Ireland’s Larger Moths

Hardback | November 2019

Atlas of Britain and Ireland’s Larger Moths includes accounts for 866 macro-moth species, each with a distribution map showing current and historical occurrences, trends, status, a phenology chart and colour image.

Britain’s Day-Flying Moths: A Field Guide to the Day-Flying Moths of Great Britain and Ireland

Britain’s Day-Flying Moths: A Field Guide to the Day-Flying Moths of Great Britain and Ireland

Flexibound | July 2019

This concise photographic field guide helps you to identify the day-flying moths most likely to be seen in Great Britain and Ireland, combining photographs, clear and authoritative text and an easy-to-use design.

Micro-Moth Field Tips + Micro-Moth Field Tips, Volume 2: A Guide to Finding the Early Stages in Lancashire and Cheshire – A Chronological Guide from January to December

Paperback | December 2021

Micro-Moth Field Tips describes how to identify the early stages of more than 170 species of micro-moth larvae at all times of the year. There are 12 chapters, one for each month, as well as recommendations on what micro-moths to look for on field trips at different times of the year. Micro-Moth Field Tips, Volume 2 follows on from the enormous success of the first volume. Designed as being complementary to the first volume, the book has an introduction to the early stages of each family of micro-moths as well as many images of leaf mines.

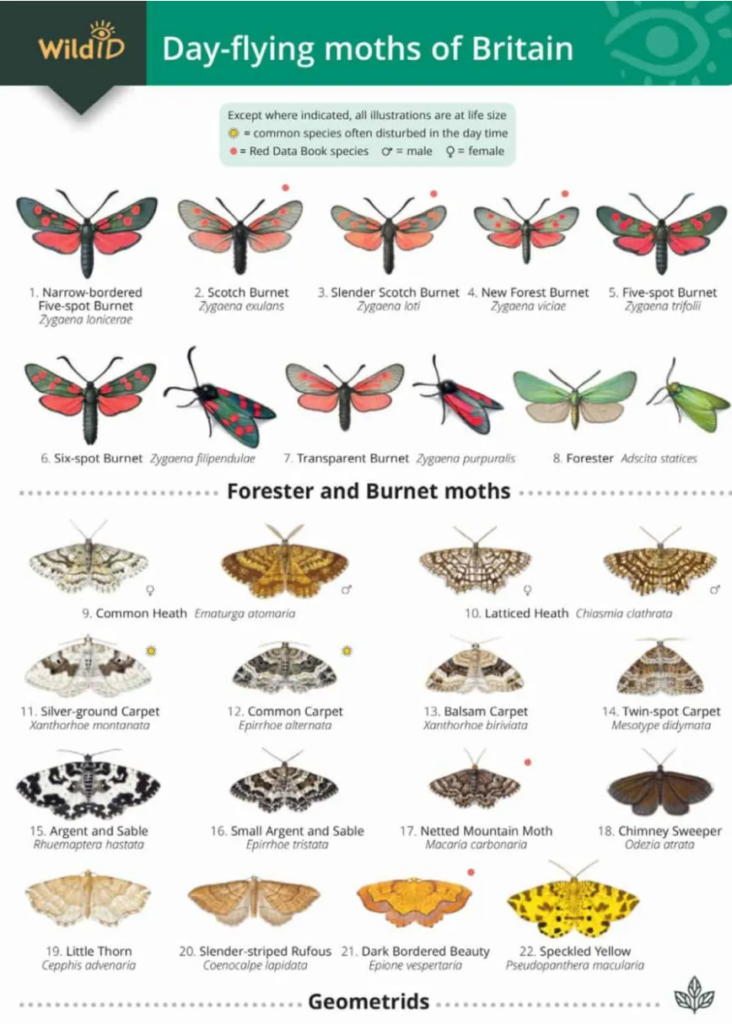

Guide to the Day-flying Moths of Britain Unbound | July 2006

This 8-page chart shows 103 species of day-flying macro-moths. Paintings show the adult moths at life size and in their natural resting postures. The text, arranged by family with full cross-referencing to images, provides further information on the habitats and distribution of illustrated species.

These 60ml sampling containers are made from see-through polypropylene and have secure screw-on lids. They’re ideal for temporarily keeping small aquatic or terrestrial specimens.

Opticron Hand Lens 22mm 10x Magnification

This Opticron Hand Lens contains a high quality 23mm doublet lens, made of glass and provides excellent distortion-free magnification. The 10x magnification is recommended for general observations and this magnifier is the one most commonly recommended for all types of fieldwork.

The NHBS moth trap is a lightweight and highly portable trap, tested and approved by Butterfly Conservation. The starter kit includes 3 x 60m clear collecting pots and the Concise Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland to help you observe and identify the species you find in your trap.

UV glasses are highly recommended when using equipment that emits UV light, such as moth traps.

In his latest book,

In his latest book,  shapes, forms and colours of the birds. They were so very different to the birds I was used to seeing in the Somerset countryside around our home. After that, every now and again I’d see footage of hummingbirds on wildlife documentaries, and began to appreciate further just how remarkable they were – what Tim Dee described as ‘strange birds: not quite birds or somehow more than birds, birds 2.0, perhaps’.

shapes, forms and colours of the birds. They were so very different to the birds I was used to seeing in the Somerset countryside around our home. After that, every now and again I’d see footage of hummingbirds on wildlife documentaries, and began to appreciate further just how remarkable they were – what Tim Dee described as ‘strange birds: not quite birds or somehow more than birds, birds 2.0, perhaps’. There were plenty of other moments that I’ll hold in my heart, and they don’t all involve the iconic, rare species. One such was watching Golden-tailed Sapphires, a hummingbird that looks as if it’s been dipped in rainbows, feeding in a clearing in the immediate aftermath of a heavy rain shower. As the sun broke through the dripping vegetation and steaming air we were suddenly surrounded by myriad small rainbows through which the birds were flying. That moment was ephemeral, over almost as soon as it began, but it’s etched in my memory forever.

There were plenty of other moments that I’ll hold in my heart, and they don’t all involve the iconic, rare species. One such was watching Golden-tailed Sapphires, a hummingbird that looks as if it’s been dipped in rainbows, feeding in a clearing in the immediate aftermath of a heavy rain shower. As the sun broke through the dripping vegetation and steaming air we were suddenly surrounded by myriad small rainbows through which the birds were flying. That moment was ephemeral, over almost as soon as it began, but it’s etched in my memory forever.  I found myself asking myself that very question as my journey into their world unfolded… Hummingbirds certainly seem to touch something deep inside us. They featured in the mythology of the Aztecs; inspired the most dramatic of all of the immense geoglyphs carved into the desert floor by the Nazca; appear in renowned art and literature; and, to this day, are singled out for particular love by those whose gardens they frequent, people who would not necessarily identify themselves as birders.

I found myself asking myself that very question as my journey into their world unfolded… Hummingbirds certainly seem to touch something deep inside us. They featured in the mythology of the Aztecs; inspired the most dramatic of all of the immense geoglyphs carved into the desert floor by the Nazca; appear in renowned art and literature; and, to this day, are singled out for particular love by those whose gardens they frequent, people who would not necessarily identify themselves as birders. Inevitably there were some logistical challenges to contend with, not least having to reacquaint myself with horse-riding after a decades-long and deliberate avoidance of it! There were a couple of close encounters with large predators that were, in hindsight, more alarming than they felt at the time – as a naturalist, I was thrilled to get (very) close views of a puma… But perhaps the most challenging moment of all was landing in Bolivia at the very moment the country was taking to the streets to protest the outcome of a recent presidential election. There was an incident at a roadblock manned by armed men that was genuinely scary, with an outcome that hung in the balance for a terrifying instant, and could easily have ended badly.

Inevitably there were some logistical challenges to contend with, not least having to reacquaint myself with horse-riding after a decades-long and deliberate avoidance of it! There were a couple of close encounters with large predators that were, in hindsight, more alarming than they felt at the time – as a naturalist, I was thrilled to get (very) close views of a puma… But perhaps the most challenging moment of all was landing in Bolivia at the very moment the country was taking to the streets to protest the outcome of a recent presidential election. There was an incident at a roadblock manned by armed men that was genuinely scary, with an outcome that hung in the balance for a terrifying instant, and could easily have ended badly. I sometimes think there’s almost too much optimism expressed when talking about conservation challenges anywhere in the world – a narrative that suggests “if we only care enough, the [insert iconic species name here] can be saved”. And to a degree, that’s good – we’ve got to have hope, as the alternative is too dreadful to countenance – but given our impact to date, and in an uncertain future where the effects of climate change are still unfolding and will continue for many decades to come, to name just the biggest of the mounting pressures on the natural world, I’m not sure that I do feel terribly optimistic, least of all for those hummingbird species that have very localized populations, or depend upon very specific habitats. They’re undeniably vulnerable. But like Fox Mulder,

I sometimes think there’s almost too much optimism expressed when talking about conservation challenges anywhere in the world – a narrative that suggests “if we only care enough, the [insert iconic species name here] can be saved”. And to a degree, that’s good – we’ve got to have hope, as the alternative is too dreadful to countenance – but given our impact to date, and in an uncertain future where the effects of climate change are still unfolding and will continue for many decades to come, to name just the biggest of the mounting pressures on the natural world, I’m not sure that I do feel terribly optimistic, least of all for those hummingbird species that have very localized populations, or depend upon very specific habitats. They’re undeniably vulnerable. But like Fox Mulder,

As recently featured on

As recently featured on  photographing and surveying insects. I learned about the insects, watched them and counted the sheer number of species, and realised that no one else had actually surveyed a small urban park extensively. The book came about as I wanted to show people what was living in the bushes and to put Peckham on the entomological map!

photographing and surveying insects. I learned about the insects, watched them and counted the sheer number of species, and realised that no one else had actually surveyed a small urban park extensively. The book came about as I wanted to show people what was living in the bushes and to put Peckham on the entomological map!

and usually open 24 hours – but there is no reason why we can’t include habitats for our wildlife. A simple solution would be to leave areas un-mowed to grow wild. In the parks of my local area in London, large swathes of grasses and flowers have been left to mature and people have been really receptive to it. I think we are finally moving away from the Victorian ideal of neat and tidy!

and usually open 24 hours – but there is no reason why we can’t include habitats for our wildlife. A simple solution would be to leave areas un-mowed to grow wild. In the parks of my local area in London, large swathes of grasses and flowers have been left to mature and people have been really receptive to it. I think we are finally moving away from the Victorian ideal of neat and tidy!

For nearly thirty years now I have been going to stay in a small house at the head of a bay on the west coast of Scotland. It is somewhere my wife’s family have been going for generations and now our children and grandchildren love it too. It has everything you might long for from a place like that: cliffs, woods, waterfalls, a dark beach made of basalt sands, a lighthouse, a ruined castle, stories, beauty, birds, fish; but one thing it did not have because of the geology, was a rockpool. For years I have dreamed of making one – a place of stillness set in the tide, and this book is the story of how I made three of them in different parts of the bay; one dug in with a pickaxe; one made by damming a narrow exit to the sea from a hollow so that the dam held the pool behind it; and one by making a circular wall low down in the intertidal.

For nearly thirty years now I have been going to stay in a small house at the head of a bay on the west coast of Scotland. It is somewhere my wife’s family have been going for generations and now our children and grandchildren love it too. It has everything you might long for from a place like that: cliffs, woods, waterfalls, a dark beach made of basalt sands, a lighthouse, a ruined castle, stories, beauty, birds, fish; but one thing it did not have because of the geology, was a rockpool. For years I have dreamed of making one – a place of stillness set in the tide, and this book is the story of how I made three of them in different parts of the bay; one dug in with a pickaxe; one made by damming a narrow exit to the sea from a hollow so that the dam held the pool behind it; and one by making a circular wall low down in the intertidal.

And so that provided the model – see what was there and look carefully at it. Of course, books like mine are entirely parasitic on the work of many generations of biologists and that too turned out to be the pattern. Watch the sand hoppers and then read about them. Read about them and see how much of what I read I could find on the shore. With prawns, winkles, shore crabs, anemones, limpets, sea-stars, urchins and barnacles, I simply oscillated between the pools and my books: what was there? What had people discovered about them? How did they interact? What were the principles governing their presence or absence? And with all of that came the repeated and slightly sobering realisation that unless I knew to look for something it was very difficult to see it was there. Mysteriously, we are often blind to what is in front of our eyes.

And so that provided the model – see what was there and look carefully at it. Of course, books like mine are entirely parasitic on the work of many generations of biologists and that too turned out to be the pattern. Watch the sand hoppers and then read about them. Read about them and see how much of what I read I could find on the shore. With prawns, winkles, shore crabs, anemones, limpets, sea-stars, urchins and barnacles, I simply oscillated between the pools and my books: what was there? What had people discovered about them? How did they interact? What were the principles governing their presence or absence? And with all of that came the repeated and slightly sobering realisation that unless I knew to look for something it was very difficult to see it was there. Mysteriously, we are often blind to what is in front of our eyes. stages, can recognise the movements and timings of the tides. That sea anemones can identify other sea anemones that are not their relations and effectively destroy them. That prawns have an imagination – that might sound like too much, but it has been shown that they can remember past pain and project it into present and future anxieties. Anxiety is different from fear; it is a fear of what might be there. In other words a prawn can think beyond its present reality.

stages, can recognise the movements and timings of the tides. That sea anemones can identify other sea anemones that are not their relations and effectively destroy them. That prawns have an imagination – that might sound like too much, but it has been shown that they can remember past pain and project it into present and future anxieties. Anxiety is different from fear; it is a fear of what might be there. In other words a prawn can think beyond its present reality. garden whose walls are dissolved twice a day, an enclosure that becomes part of the general world with every high tide. That ambiguity is what entranced me, the sense of its being a micro-ocean, a micro-arcadia, a micro-laboratory in which all kinds of intimacies and precision in natural beings can be witnessed an inch beneath your nose.

garden whose walls are dissolved twice a day, an enclosure that becomes part of the general world with every high tide. That ambiguity is what entranced me, the sense of its being a micro-ocean, a micro-arcadia, a micro-laboratory in which all kinds of intimacies and precision in natural beings can be witnessed an inch beneath your nose.

The

The

And most importantly – just go out there and watch mammals. I may be biased, but for me there is nothing better than being out in the countryside early on a spring morning watching the hares chasing around and knocking seven bells out of each other. You might like to stay up late watching badgers or bats, or enjoy the crazy antics of a squirrel on a bird feeder. It’s important that we engage with nature and encourage our children to do the same. If we don’t see and understand wildlife, we won’t fight for it. And, trust me, we need to fight for it.

And most importantly – just go out there and watch mammals. I may be biased, but for me there is nothing better than being out in the countryside early on a spring morning watching the hares chasing around and knocking seven bells out of each other. You might like to stay up late watching badgers or bats, or enjoy the crazy antics of a squirrel on a bird feeder. It’s important that we engage with nature and encourage our children to do the same. If we don’t see and understand wildlife, we won’t fight for it. And, trust me, we need to fight for it.