Bats are elusive creatures; they are nocturnal, and so you are less likely to spot them compared to other UK wildlife, despite bats making up almost a quarter of our native mammal species within the UK. Some species have experienced severe declines, although current trends indicate that a few of these are now recovering. There is still much to learn about bats, however, and ongoing monitoring plays an important role in improving our knowledge of bat population trends.

Where to find them?

Bats are more likely to be found roosting in natural crevices, as opposed to building nests like birds or other small mammals. They can roost in trees, roofs, or outdoor cavities in buildings such as houses, as well as other natural or manmade structures, such as caves and bridges. As they hibernate during the winter, bats are the most active between April and November, and the best time of day to watch them is at dusk. They’re found in many habitats, particularly woodlands, farmland and urban areas (such as gardens).

Identifying Bats:

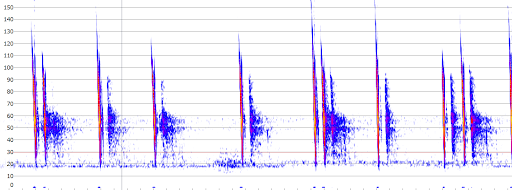

There are 17 species of bats that have breeding populations in the UK. They are commonly identified by their calls, as the rhythm, frequency range and repetition rate varies between species. A bat detector can be used to easily identify individual bat species in the field; you can browse our range here. In this article, however, we will be looking specifically at the physical characteristics that aid in the identification of 11 of our more common bat species.

Their size, colouration, nose shape, and the size and shape of their ears are helpful features to look at when identifying them by sight. More complicated identification features include the presence and size of the post calcarial lobe, a lobe of skin on the tail membrane, and the length of the forearm.

Pipistrelles

The most common species, and the ones you’re most likely to see, are pipistrelles. There are three species, the common pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus), the soprano pipistrelle (P. pygmaeus), and the Nathusius’ (P. nathusii), with the first two being the most common and widespread of all UK bat species.

ID notes: All three species look very similar, with dark brown fur, a paler underside, and a darker mask-like pattern around the face. Nathusius’s pipistrelles are rarer, and slightly more easy to tell apart due to their lighter underside, larger body size, and furrier tail.

Size: 3.5-4.5cm in length (Nathusius’: 4.6-5.5cm)

Wingspan: 20-23cm (Nathusius’: 22-25cm)

Great and Lesser Horseshoe Bats

Latin names: Rhinolophus ferrumequinum and R. hipposideros

ID notes: Both these species have a fleshy nose shaped like a horseshoe. The lesser horseshoe is much smaller, with greyish-brown fur on its back and a white underside, while the greater horseshoe is larger and has more of a reddish-brown colouration on its back and a cream underside.

Size: Lesser: 3.5-45cm in length, Greater: 5.7-7cm in length

Wingspan: Lesser: 20-25cm, Greater: 35-40cm

Whiskered Bat:

Latin name: Myotis mystacinus

ID notes: The whiskered bat is quite difficult to distinguish as they are visually similar to Brandt’s bats. They have brown or dark grey fur with gold tips, and a lighter grey underside. They have a concave posterior edge to their tragus, the piece of skin of the inner ear in front of the ear canal, whereas Brandt’s bats have a convex posterior edge.

Size: 3.5-4.8cm

Wingspan: 21-24cm

Daubenton’s Bat

Latin name: Myotis daubentoniid

ID notes: This bat has brown fur, a paler underside that appears silvery-grey, and a pink face. This species is most likely seen around water as they forage for small flies above and on the water’s surface.

Size: 4.5-5.5cm

Wingspan: 24-27cm

Brown and Grey Long-eared Bats

Latin name: Plecotus auratus and P. austriacus

ID notes: These bats, as their names suggest, have very long, large ears which can be almost the same length as their bodies. These species look very similar, with greyish-brown fur, although the grey long-eared bat has a darker face.

Size: Brown: 3.7-5.2 cm, Grey: 4.1-5.8cm

Wingspan: Brown: 20-30cm, Grey: 25-30cm

Natterer’s Bat

Latin name: Myotis nattereri

ID notes: The Natterer’s bat has a bare, pink face and light brown and grey fur on its back, with a paler underside. Its ears are quite long, and it has bristles along its tail membrane.

Size: 4-5cm

Wingspan: 24.5-30cm

Bechstein’s Bat

Latin name: Myotis Bechsteinii

ID notes: The Bechstein’s bat has long ears which, unlike the barbastelle’s, do not meet at the forehead. Their fur is reddish-brown with a paler, grey underside, and a pink face.

Size: 4.3-5.3cm

Wingspan: 25-30cm

All bat species are European protected species, therefore they and their breeding and resting sites are fully protected by the law. It is important to note that a licence is required for capturing and handling bats, as well as for any activity that may disturb a bat roost, including photography.

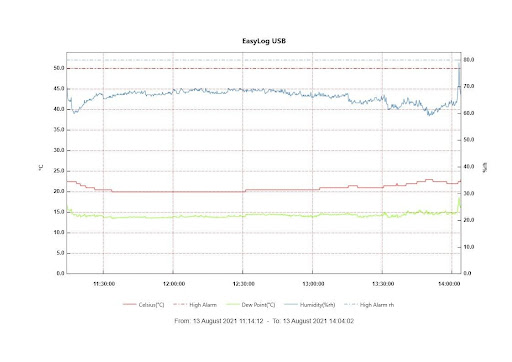

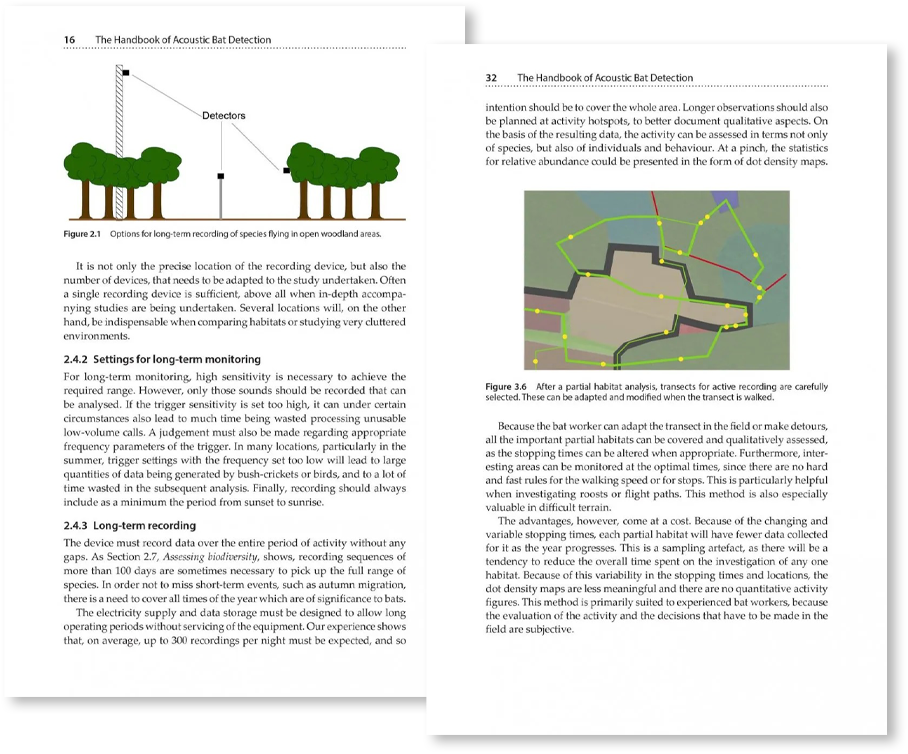

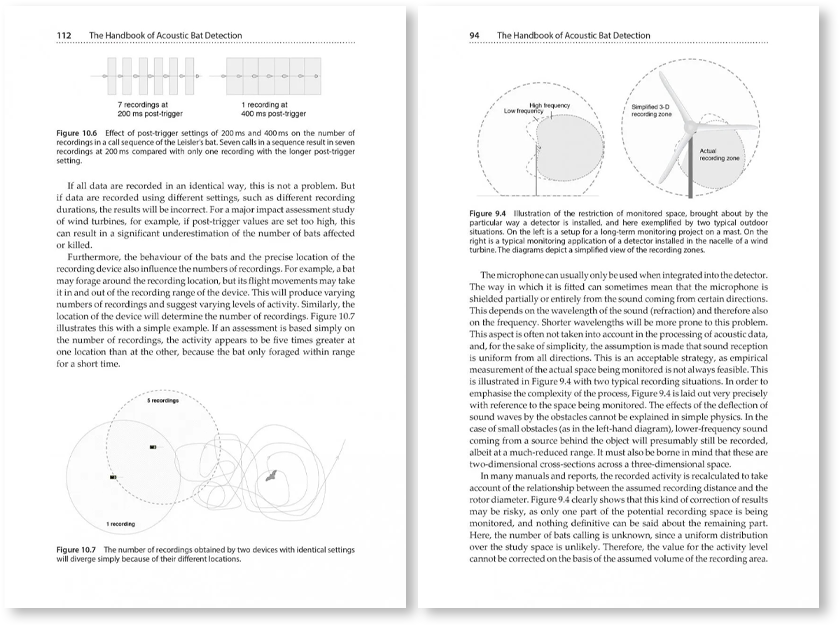

Acoustic detection is a popular and widespread method of environmental assessment, and its use is increasing, driven by the development of increasingly accessible and sophisticated detection devices.

Acoustic detection is a popular and widespread method of environmental assessment, and its use is increasing, driven by the development of increasingly accessible and sophisticated detection devices.

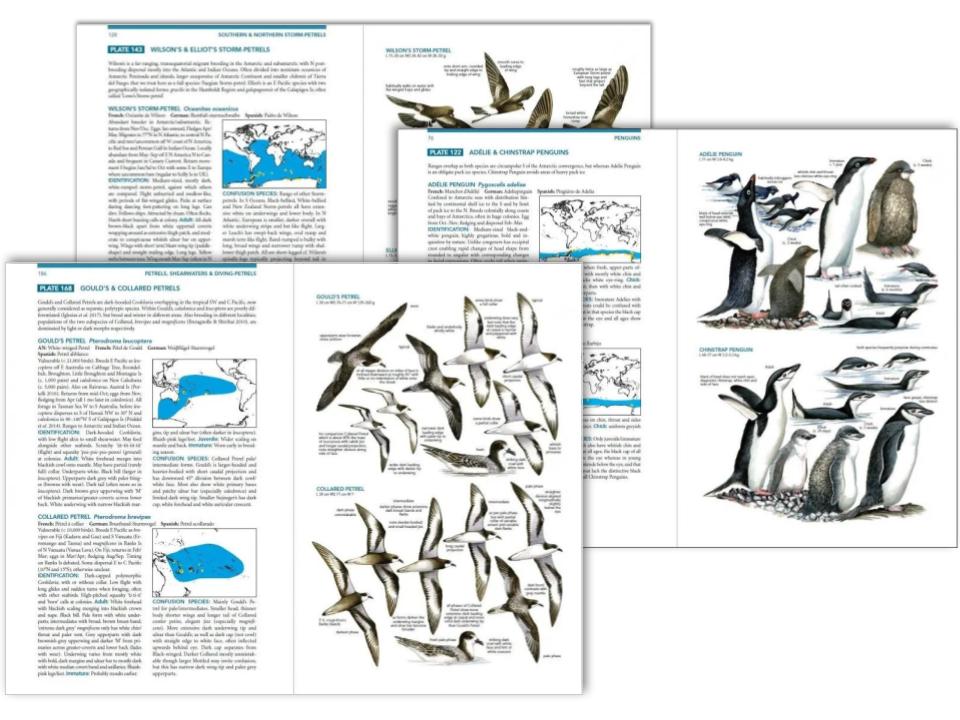

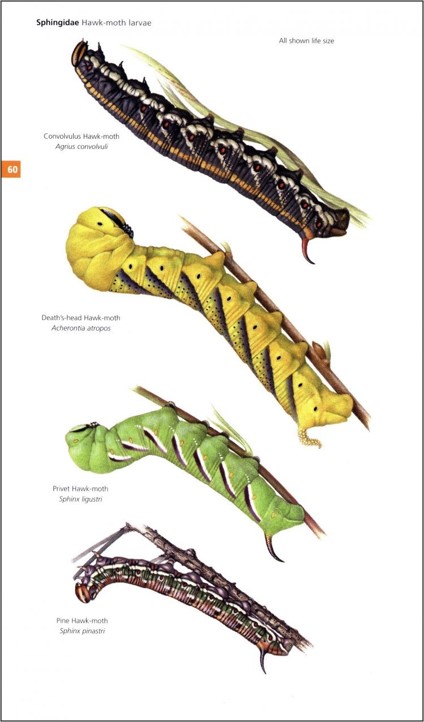

This field guide includes beautiful illustrations displaying key features to help with identification. It covers flight season, life cycle, larval foodplants, habitat and more, along with maps presenting distribution information.

This field guide includes beautiful illustrations displaying key features to help with identification. It covers flight season, life cycle, larval foodplants, habitat and more, along with maps presenting distribution information.

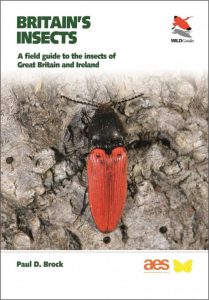

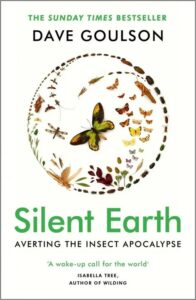

natural world and to human society. With an expert eye, Goulson skillfully guides the reader through different aspects of their importance, from the multi-million pound service that dung beetles provide the farming industry each year in the UK alone to the vital role that pollinators play in underpinning ecosystems across the planet, and the value that insects have in their own right as beautiful, vibrant denizens of our planet. The author’s passion is infectious; it is difficult to read this section without becoming invested in the wondrous ranks of the planet’s invertebrates, making the threat of their decline feel all the more personal.

natural world and to human society. With an expert eye, Goulson skillfully guides the reader through different aspects of their importance, from the multi-million pound service that dung beetles provide the farming industry each year in the UK alone to the vital role that pollinators play in underpinning ecosystems across the planet, and the value that insects have in their own right as beautiful, vibrant denizens of our planet. The author’s passion is infectious; it is difficult to read this section without becoming invested in the wondrous ranks of the planet’s invertebrates, making the threat of their decline feel all the more personal.  controversial among some parties. He consistently highlights the arguments of his critics, treating them with respect and validation. At some points he provides his rebuttal while at others he admits to the shortcomings of the relevant research, explaining why a different approach was impossible at the time. This is indicative of an attitude that permeates the book – the issues that he writes about are bigger than minor gripes with experimental methodologies, bigger than business margins or political leanings. He presents with a neutral eye the irrefutable reality that insects are vanishing at a terrifying rate, and unless action is taken the world is heading towards a very real disaster within generations. Though frequently distressing and at times heartbreaking, Goulson writes with a voice compelling and just witty enough to prevent the reader from becoming despondent. This book is not intended to drive us to despair, but to action.

controversial among some parties. He consistently highlights the arguments of his critics, treating them with respect and validation. At some points he provides his rebuttal while at others he admits to the shortcomings of the relevant research, explaining why a different approach was impossible at the time. This is indicative of an attitude that permeates the book – the issues that he writes about are bigger than minor gripes with experimental methodologies, bigger than business margins or political leanings. He presents with a neutral eye the irrefutable reality that insects are vanishing at a terrifying rate, and unless action is taken the world is heading towards a very real disaster within generations. Though frequently distressing and at times heartbreaking, Goulson writes with a voice compelling and just witty enough to prevent the reader from becoming despondent. This book is not intended to drive us to despair, but to action.  encouraging native plants in our towns and cities and overhauling the way in which we view farming. Finally, there is an extensive list of actions, large and small, that people can take, listed by occupation. This section is what the book has been building to, and it is worth reading for this alone. As usual, respect is paid to all viewpoints and all members of society. It doesn’t matter whether the reader is in a position where a free-range organic, locally sourced diet is financially viable or not – there will be other actions that they can take regardless of financial matters. Nor does it matter if they have beliefs, political or economic, that might conflict with the author’s. It is a call for society to overlook such matters which are, in the face of such a crisis, trivial.

encouraging native plants in our towns and cities and overhauling the way in which we view farming. Finally, there is an extensive list of actions, large and small, that people can take, listed by occupation. This section is what the book has been building to, and it is worth reading for this alone. As usual, respect is paid to all viewpoints and all members of society. It doesn’t matter whether the reader is in a position where a free-range organic, locally sourced diet is financially viable or not – there will be other actions that they can take regardless of financial matters. Nor does it matter if they have beliefs, political or economic, that might conflict with the author’s. It is a call for society to overlook such matters which are, in the face of such a crisis, trivial.