British Wildlife has featured book reviews since the very first magazine back in 1989. These reviews provide in-depth critiques of the most important new titles in natural history publishing, from nature-writing bestsellers to technical identification handbooks. They are all authored by experts in relevant subjects, which ensures an honest and insightful appraisal of each book featured.

Since 2018 every review included in the magazine is available to read on the British Wildlife website. Here are ten titles that have featured so far in some of the recent issues of British Wildlife, all with links to take you directly to the full review.

1. Beak, Tooth and Claw: Living with Predators by Mary Colwell

“She walked and travelled through the farms and uplands of Britain and Ireland. She talked to people on both sides of the divide – sheep-farmers, salmonfishers, raven-tamers, writers, scientists, conservationists, gamekeepers. She watched her chosen predators in the field and noted how they ‘fit into the landscape’.”

“She walked and travelled through the farms and uplands of Britain and Ireland. She talked to people on both sides of the divide – sheep-farmers, salmonfishers, raven-tamers, writers, scientists, conservationists, gamekeepers. She watched her chosen predators in the field and noted how they ‘fit into the landscape’.”

Reviewed by Peter Marren in the June 2021 issue (BW 32.7) – read the review here

2. Broomrapes of Britain & Ireland by Chris Thorogood & Fred Rumsey

“This monograph has been meticulously proofread, and is neatly laid out, well printed and generally excellent. I am particularly grateful to the authors for finally nailing down a violet-coloured broomrape which I found, years ago, growing on the seashore near Sandwich.”

“This monograph has been meticulously proofread, and is neatly laid out, well printed and generally excellent. I am particularly grateful to the authors for finally nailing down a violet-coloured broomrape which I found, years ago, growing on the seashore near Sandwich.”

Reviewed by Peter Marren in the August 2021 issue (BW 32.8) – read the review here

3. Much Ado About Mothing: A Year Intoxicated by Britain’s rare and Remarkable Moths by James Lowen

“Most of his literary energy lies in individualising the moths. He is a generous and imaginative, and, yes, ‘intoxicated’ describer. The quest has barely got going before we are introduced to the Pale Tussock’s ‘shag-pile furriness’ and the male Muslin Moth’s ‘grey mad-professor hair’.”

Reviewed by Peter Marren in the August 2021 issue (BW 32.8 – read the review here

4. Butterflies by Martin Warren

“In summary, I have nothing but praise for this book. Anyone interested in butterflies, and especially those involved with sites where butterflies are a significant presence, should read it. It is beautifully produced and printed.”

Reviewed by Bob Gibbons in the August 2021 issue (BW 32.8) – read the review here

5. International Treaties in Nature Conservation: A UK Perspective by David Stroud et al.

“It is therefore authoritative and densely packed, yet commendably succinct, well paced and easy to read. Inevitably specialist, it is nevertheless a compelling read and will become a worthy source of reference for years to come.”

Reviewed by Anthony Fox in the October 2021 issue (BW 33.1) – read the review here

6. Why Nature Conservation Isn’t Working: Understanding Wildlife in the Modern World by Adrian Spalding

“We deliberately choose big, glamorous species to release simply because we like them. Spalding thinks that all this is wrong, that wild species have an existence entirely separate from Homo sapiens in time and space, in their lives, in their habitat, and in their evolutionary and historical past (and future).”

Reviewed by Peter Marren in the October 2021 issue (BW 33.1) – read the review here

7. Human, Nature: A Naturalist’s Thoughts on Wildlife and Wild Places by Ian Carter

“As Ian Carter puts it, the many and varied connections he has with nature play a significant part in making his life feel worthwhile. They have provided the material for the journals he has kept over three decades, and form the substance of this book. His thoughts on the conundrums and contradictions in the way humans interact with wildlife build into a thoughtful and timely look at contemporary relationships between people and nature.”

Reviewed by James Robertson in the October 2021 issue (BW 33.1) – read the review here

8. Ecology and Natural History by David M. Wilkinson

“Although it is clearly written, and eschews mathematics, it is dense with concepts and facts, with a strong whiff of university teaching. It is therefore one of the more technical New Naturalists. But where does it say that nature has to be simple? Its complexity is surely part of its fascination.”

Reviewed by Peter Marren in the October 2021 issue (BW 33.1) – read the review here

9. Freshwater Snails of Britain and Ireland by Ben Rowson et al.

“This is a terrific book: a ‘must have’ for anyone who wants to learn how to identify, accurately, freshwater snails in Britain and Ireland.”

Reviewed by Jeremy Biggs in the November 2021 issue (BW 33.2) – read the review here

10. Britain’s Insects: A Field Guide to the Insects of Great Britain and Ireland by Paul D. Brock

“Its structured approach offers a general illustrated guide to insect orders (such as mayflies, or dragonflies and damselflies), including some larvae. Then, when you reach an order, there is a good introduction and the species accounts are further broken down into sections…”

Reviewed by Bob Gibbons in the November 2021 issue (BW 33.2) – read the review here

Since its launch in 1989, British Wildlife has established its position as the leading natural history magazine in the UK, providing essential reading for both enthusiasts and professional naturalists and wildlife conservationists. Individual back issues of the magazine are available to buy through the NHBS website, while annual subscriptions start from just £35 – sign up online here.

A Field Guide to the Plants of Armenia

A Field Guide to the Plants of Armenia

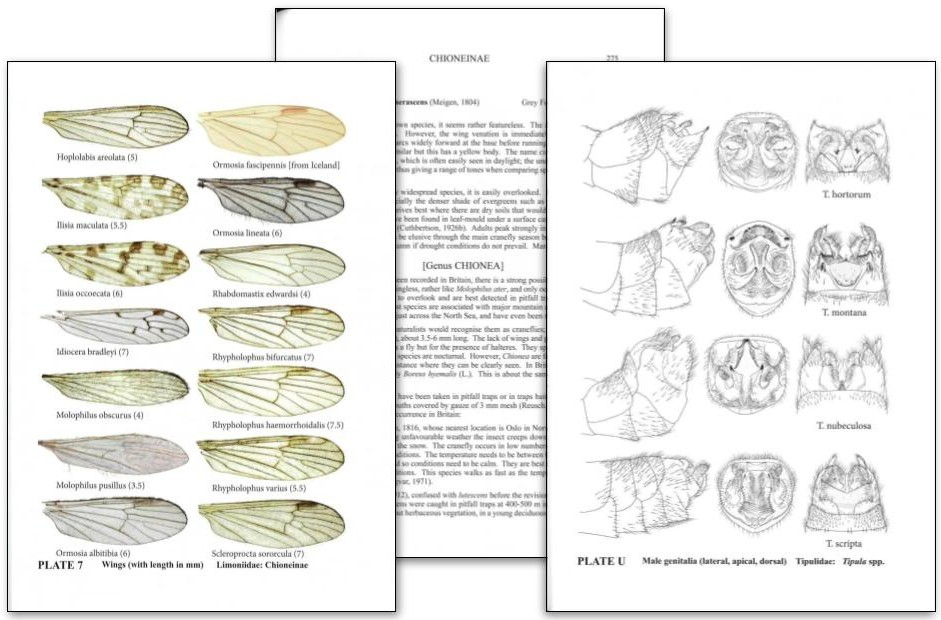

British Craneflies

British Craneflies