In this bracing yet hopeful exploration of the future of the ocean, Helen scales relays the fascinating, deep history of our seas and reveals how prehistoric ecology holds lessons for the oceans of today. In light of the current challenging climate conditions, she offers innovative ideas to protect our coastlines and the species who live there, highlighting the importance of ethical and sustainable fisheries, the threat posed by deep-sea mining and more. This inspiring tale urges us to fight for a better future for the ocean before it’s too late.

In this bracing yet hopeful exploration of the future of the ocean, Helen scales relays the fascinating, deep history of our seas and reveals how prehistoric ecology holds lessons for the oceans of today. In light of the current challenging climate conditions, she offers innovative ideas to protect our coastlines and the species who live there, highlighting the importance of ethical and sustainable fisheries, the threat posed by deep-sea mining and more. This inspiring tale urges us to fight for a better future for the ocean before it’s too late.

Helen Scales is a marine biologist, author and broadcaster who teaches Marine Biology and Science Writing at the University of Cambridge. She regularly writes on ocean discoveries for National Geographic Magazine and The Guardian, is an avid scuba diver, cold-water surfer and trained free diver who has lived and worked around the world, and is currently spending her time between Cambridge and the wild Atlantic coast of France.

We recently had the opportunity to talk to Helen about her most recent book What The Wild Sea Can Be, including how she first became a marine biologist, how we can secure a better future for our oceans, her current projects and more.

Firstly, can you tell us a little about yourself, your career, and how you came to be a marine biologist?

For as long as I can remember, I’ve loved nature and being outdoors. My family spent a lot of holidays in Cornwall, so my training grounds as a marine biologist were windswept Atlantic beaches. This is when I began my lifelong love of rock pooling, shell collecting and rummaging around in seaweed to see what I can find.

As a teen, I became a committed environmentalist. I was outraged by the issues of the day, including deforestation in the Amazon, and became vegetarian. Around the time I was beginning to contemplate a career as an environmental scientist, a school friend and I decided to take up scuba diving. We lived in land-locked, suburban Surrey – not an obvious place to learn to dive – but there was a friendly dive club that met each week and trained at the local swimming pool in an enclosed sea of eye-stinging chlorination. Our open water training dives were mostly back down in Cornwall, and that’s where I truly fell in love with the ocean and knew that I wanted to become a marine biologist. Instead of running off to save the rainforests, I wanted to save the ocean. I often say that was when my vision for my future turned from green to blue.

So I left school, diving licence in hand, and immediately headed off on adventures to explore more of the seas. I’ve been incredibly lucky to travel to many corners of the ocean, studying and researching, and taking every opportunity I could to get myself underwater. For my PhD, I went to Borneo and studied the lives and loves of one of the biggest and I think most beautiful fish on coral reefs, the Humphead Wrasse.

Over the years, I’ve worked for various conservation organisations, including WWF in Malaysia where I mapped marine life around an archipelago of coral islands. Later, I worked on efforts to control the global trade in endangered marine species. Then, quite out of the blue, I discovered a previously unknown passion for writing and presenting, and decided to focus on sharing stories with people about the wonders and troubles of the living ocean.

This book is cautiously optimistic about marine conservation. What have been the most impactful positive actions that have helped the recovery and management of our oceans?

A big part of my optimism for the future is the fact that ocean life has an incredible capacity to recover and heal, given a chance. Often all it takes is for people to stop hunting and killing so many animals.

For instance in the 1980s, commercial whaling was banned following the successful Save the Whales campaign, and now we’re seeing many whale populations doing a lot better. Back in the mid 20th century, whalers had killed around 99% of the Blue Whale subspecies from Antarctica, the biggest animals ever known to exist. Just recently, hydrophones stationed in the Southern Ocean have been detecting the songs of Blue Whales, a good sign that their numbers are on the rise.

Recoveries are happening in many other ocean species. After being gone for decades, Bluefin Tuna are showing up again around Britain, in part because catches have been better controlled in the Atlantic. Populations of oceanic sharks, like Great Hammerheads and Great White Sharks, are gradually increasing in the western Atlantic following years of overfishing. Up until the 1990s, the United States had a policy that actively encouraged shark exploitation. These wild animals were classified as an underutilised resource. That didn’t go well for sharks and their populations crashed. Finally, attitudes shifted, and the government rolled back the shark killing incentives and introduced measures to protect them in commercial and recreational fisheries.

Another proven way to let the ocean recover is to leave parts completely alone. That means no fishing or exploitation of any kind. People have been trying out these kinds of highly protected marine reserves for decades and showing that this is a powerful way to let nature in the ocean heal, grow and proliferate – not just inside the watery reserve boundaries but outside too.

Some of these reserves are quite tiny, and some are enormous. At both big and small scales there can be tremendous benefits for wildlife and for people when these kinds of reserves are well designed and well enforced. In Scotland, a tiny reserve off the island of Arran has helped seabed ecosystems recover and flourish from years of trawling; Lamlash Bay is now home to lots more big lobsters and scallops, and the fragile habitat-forming seaweed called maerl. And in the middle of the Pacific, the vast Papah?naumoku?kea Marine National Monument covers more than 1.5 million square miles of sea, including the spawning grounds of migratory Yellowfin and Bigeye Tuna whose numbers are increasing.

The entire ocean will never be strictly protected. What’s needed are more of these kinds of carefully located and well–enforced reserves – to protect important places like the spawning grounds of rare and endangered species, and safeguard deep sea mounts covered in rich coral and sponge gardens – combined with wider measures to sustainably manage the rest of the ocean.

What the Wild Sea Can Be discusses possible solutions to the big problems that humanity will face in terms of future oceans. Are you aware of any lesser-known or less popular solutions that could be beneficial in securing a sustainable ocean?

Certain solutions for a sustainable ocean tend to be unpopular among powerful people who are creaming off profits from the seas, often at huge industrial scales. Take the factory ships that head to Antarctica to extract krill. These finger-sized crustaceans are hunted by truly massive ships. One recently built in China is 140m (460ft) long – longer than a football field. The technique for catching krill involves lowering down giant nets and pumping up hundreds of tonnes of krill every day, working nonstop for weeks at a time. The krill is processed on board, mashed and ground to make fishmeal and oils, and most of it is destined for fish farms to be fed to livestock like salmon.

Krill are fantastically abundant in the Southern Ocean. The snag is that the places where fisheries target krill in their densest, largest shoals are the very same places where Antarctic wildlife flocks to feed on them. Whales, seals, penguins and seabirds depend on krill. Studies suggest that fisheries depleting local krill populations can make it tough for other animals to find enough food, especially penguins during their nesting season.

To make matters worse, krill and their predators are also in the firing line of the climate crisis. The Antarctic Peninsula is one of the fastest heating places on the planet. Sea ice is retreating, upsetting the life cycle of krill that depend on the ice.

Proposals to protect more of the seas around the West Antarctic Peninsula and restrict where fishing can happen are being met with strong opposition from nations with major krill fishing interests. There are many other examples where vested interests and powerful lobbies are blocking progressive changes to the way people use the ocean.

In chapter ten you discuss the idea of futuristic, ocean floating cities in the Maldives. Do you think highly engineered solutions such as these have a place in a sustainable future? And how realistic do you think these innovative adaptations are as a long-term solution?

It’s only going to be rich nations that can afford expensive, engineered solutions at a large enough scale to be significant. Perhaps there are people in the Maldives who will be able to afford this, but I’m guessing not an average fishing family whose island homes are disappearing beneath the waves. The situation in the Maldives is grim and it’s hard to know what to do in low-lying, island nations that have so little time, so I understand why people are exploring ideas of floating cities and other extreme measures.

Elsewhere, more realistic and frankly exciting solutions involve working with nature, not against it. Wetland habitats, like salt marshes and mangrove forests, are excellent at protecting against flooding and storms, and they bring heaps of other benefits too, from carbon sequestration to supporting local fisheries.

A priority for living with the future ocean is to protect and nurture existing wetlands, especially those near big cities, and to find smart ways of weaving those green solutions into more conventional approaches to protecting coastlines.

This book is a realistic, yet hopeful exploration of the future of our marine environment. Where do you think we should focus our attention over the next ten years to secure a better future for our oceans?

There are a few key things that I think need attention in the ocean in the years ahead. It will be critical to turn off the tap of plastics entering the ocean. To do that, plastic production needs to be limited globally. Currently, the amount being made annually is skyrocketing, and recycling rates have stagnated at around 10%. A global treaty on plastics is being negotiated at the United Nations which could pave the way to turning around the plastics juggernaut.

There needs to be a cultural shift away from treating the ocean as a resource to exploit and squeeze profit from. A new mindset is beginning to take hold embracing an alternative view, one of cultivation and investment. People are producing low-impact, ethical seafood, for instance growing shellfish and seaweed. Governments need to support initiatives like these, instead of propping up damaging industrial fisheries. The ocean has the capacity to provide sustainable food for millions of people, especially in food-insecure nations who have no alternatives and depend most on the seas, but not if damaging industrial fishing continues to dominate.

New ways to recklessly exploit the ocean need to be stopped before they start, in particular deep-sea mining. Mining corporations want to extract metal-rich rocks from the seabed many miles beneath the waves, in the process destroying vital deep-sea habitats and species, potentially causing widespread pollution and disrupting the health of the ocean.

The argument for deep-sea mining is that this would be a better way to provide materials for a green economy, in particular to build electric car batteries. For many reasons, this logic is deeply flawed. For one thing, the EV market is fast moving, and companies are constantly inventing new technologies in the race to build lighter, faster-charging batteries. Increasingly, the types of metals that could come from the deep, such as cobalt and lithium, are likely to be replaced by more readily available and less problematic materials.

There’s growing pushback from civil society, governments, indigenous groups, scientists and industry leaders who agree that deep-sea mining is not vital for green economies and would permanently harm the ocean.

What’s next for you? Do you have any current projects that you would like to share with us?

A few years ago I began writing books for younger readers and it’s become a part of my work that I treasure. I have a lot of fun telling stories about the seas and sea life to younger audiences, and I love collaborating with super talented artists who make such incredibly beautiful books. So, I have several more books for little ones in the pipeline.

There are also some spin offs from the books I’ve already written. When I set out on my career as a marine biologist, I never imagined one day I would have my own jigsaws!

What the Wild Sea Can Be is available to order from our online bookstore.

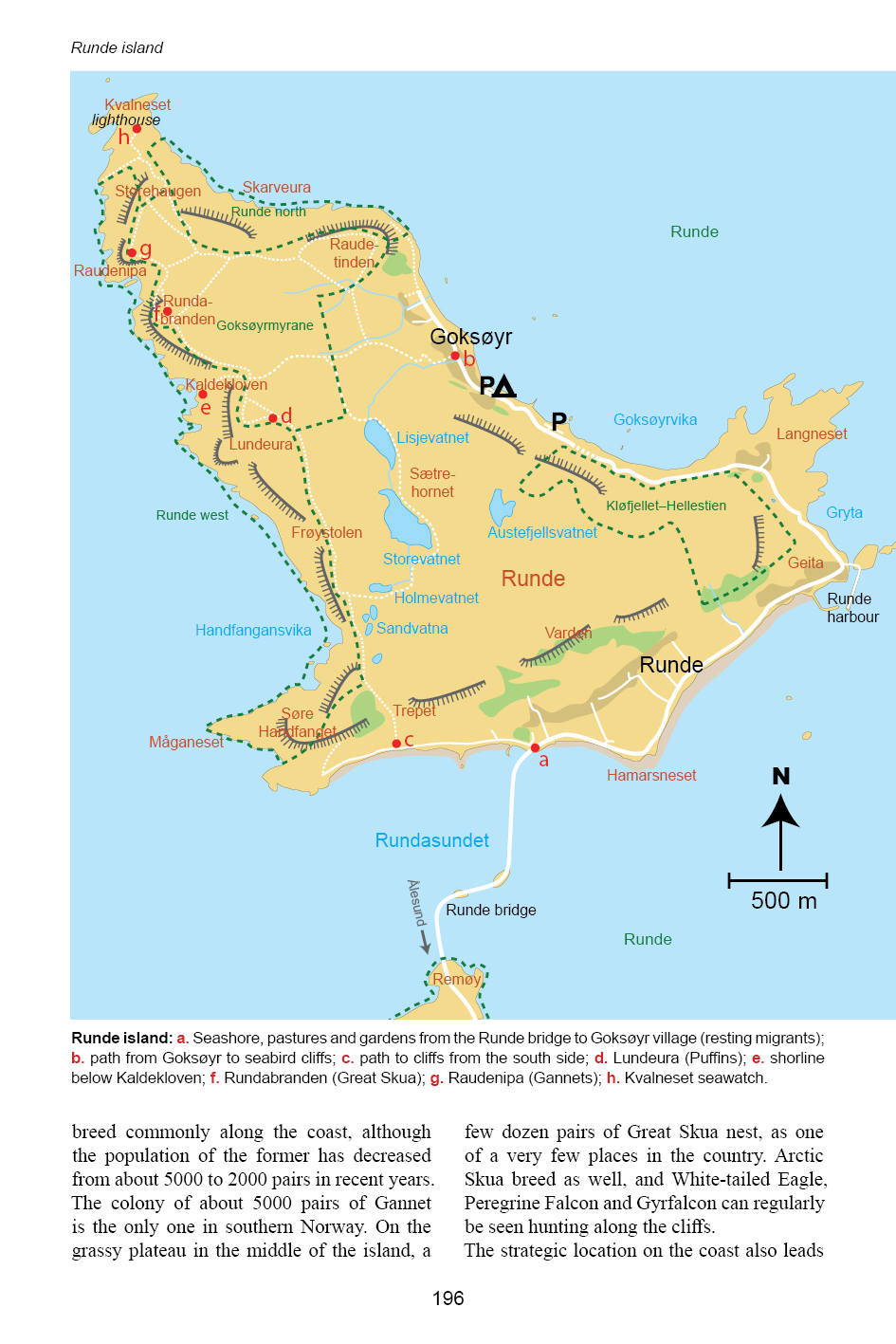

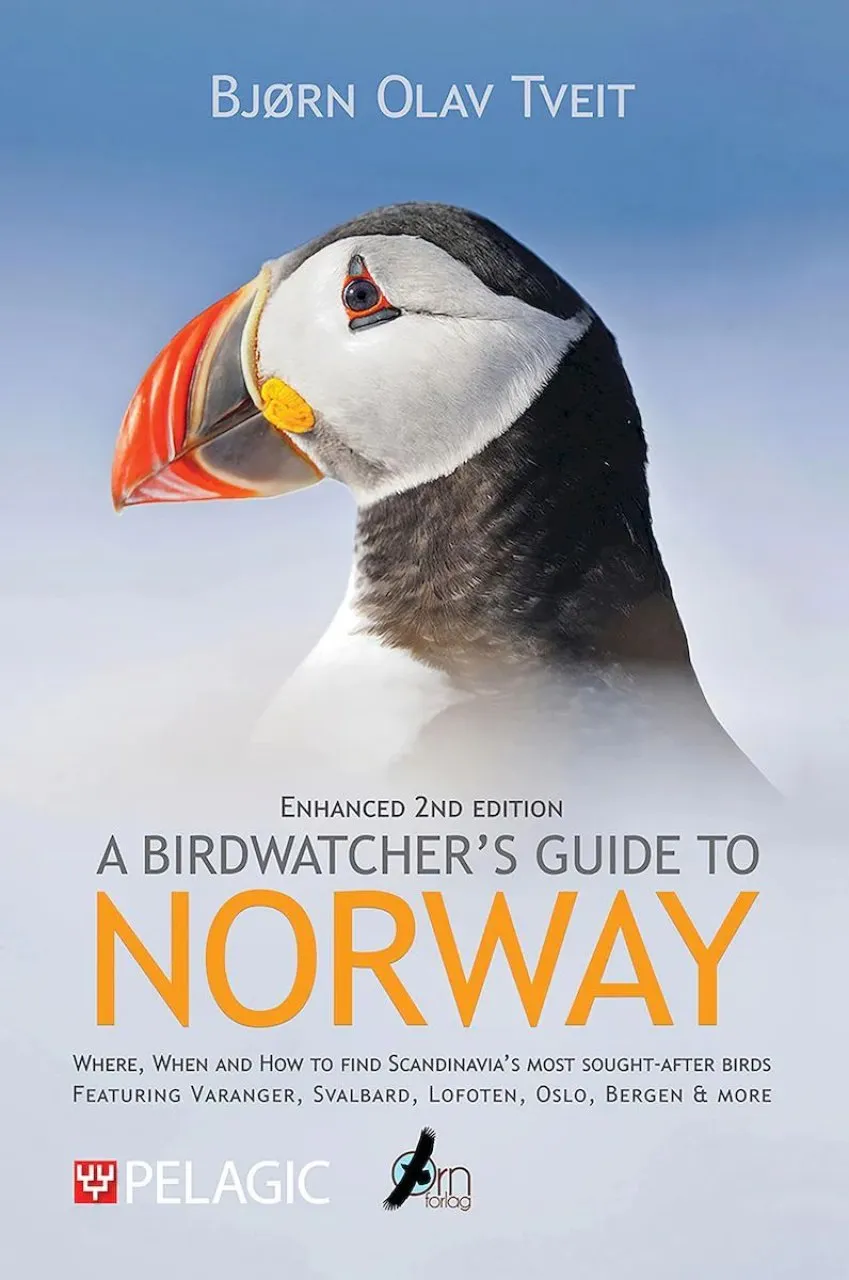

Bjørn Olav Tveit lives in Oslo, Norway and has explored many of the country’s best birding sites throughout his life. He is a long-standing member of the Norwegian Rarity Committee for Birds and acts as the nature conservation contact for his local BirdLife Norway division. He runs bird-spotting guided tours for nature enthusiasts, composes music, authors books and works for the Norwegian Ministry of Culture.

Bjørn Olav Tveit lives in Oslo, Norway and has explored many of the country’s best birding sites throughout his life. He is a long-standing member of the Norwegian Rarity Committee for Birds and acts as the nature conservation contact for his local BirdLife Norway division. He runs bird-spotting guided tours for nature enthusiasts, composes music, authors books and works for the Norwegian Ministry of Culture. Firstly, can you tell us a little about yourself and how you got into birdwatching?

Firstly, can you tell us a little about yourself and how you got into birdwatching?