Designed and manufactured by NHBS, the professional hand net is a

popular net choice for pond dipping and kick sampling. It is lightweight,

durable and practical, and used by universities and professional

institutions.

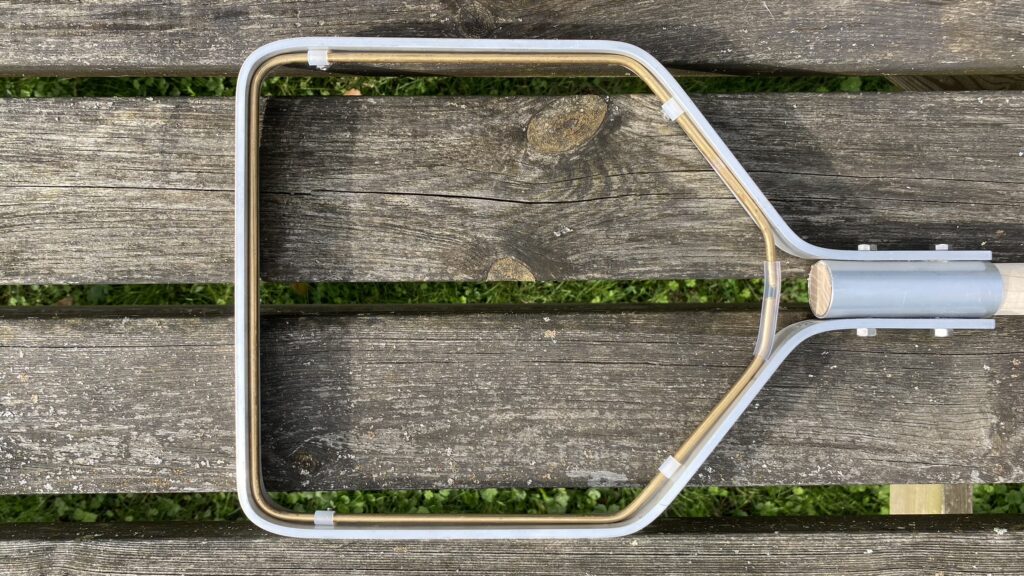

The professional hand net is available with a wide variety of mesh sizes and two net depths: standard and deep. The frame and net bags can be bought separately, allowing you to customise your hand net depending on your requirements. The standard outer frame width is 250mm and other 200mm and 300mm wide versions are available. The hand net can also be bought with two- or three-part collapsible frames to allow for ease of transport.

The professional hand net is available with a wide variety of mesh sizes and two net depths: standard and deep. The frame and net bags can be bought separately, allowing you to customise your hand net depending on your requirements. The standard outer frame width is 250mm and other 200mm and 300mm wide versions are available. The hand net can also be bought with two- or three-part collapsible frames to allow for ease of transport.

The sturdy metal frame is manufactured using marine-grade aluminium with an inner brass frame for net bag attachment, granting considerable resistance to wear and tear in the field.

Both aluminium and wooden handles are available, the benefits of the wooden handle being that it floats and is comfortable to use in colder conditions.

Net and mesh sizes

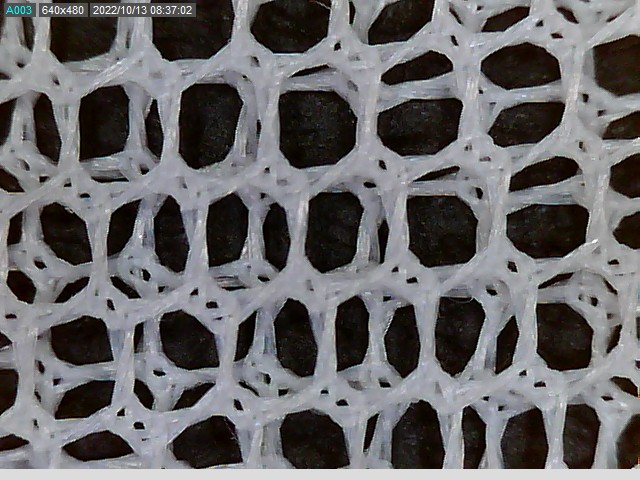

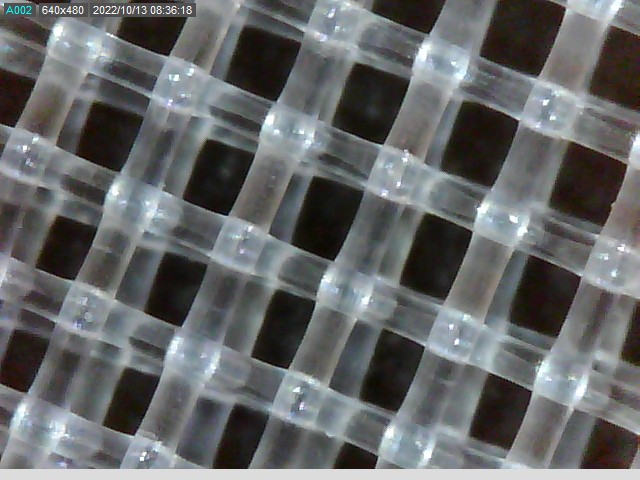

Mesh sizes range from 53µm up to 2mm. Net bags are also available in both standard (30cm) and deep (50cm) sizes.

For extra durability small mesh sizes are made from precision welded nylon material and the 1mm and 2mm mesh bags are made from woven polyester material.

The 1mm mesh is the most commonly used size for aquatic and kick sampling and the 2mm is more suited for amphibian surveys. Smaller precision meshes can be used for sampling smaller organisms such as plankton and chironomids.

Changing nets

Net bags can be attached and detached from the frame so that multiple nets can be used with a single frame. This can be handy for washing and replacing nets or when using different net meshes for sampling different organisms.

To demonstrate how to attach a net to the hand net frame, we have gone step by step through this process.

Steps

Begin by removing the inner brass frame from the outer aluminium frame by undoing the set screws from the outside of the frame using an allen key or use a spanner to loosen the nuts on the inside of the frame.

After removing the nuts, set screws and plastic clips, slide the net bag onto the now free inner brass frame using the slots in the orange section of the bag. Ensure the two upper slots are positioned just below the corners of the frame. It may be preferable to remove the plastic tube that connects the ends of the inner frame before feeding the frame into the net bag and reconnecting it.

The plastic clips can now be clipped onto the brass frame in the slots of the net bag. Ensure the flat side of the clip is facing the outside.

Place the clip flush against the hole in the outer metal frame and insert the set screw through the hole in the clip and the frame. The holes in the outer frame are off-centred, so ensure the holes are nearer to you when fixing the clips to allow the brass inner frame to sit flush with the edge of the outer frame.

The nut should then be loosely tightened onto the set screw using a spanner or by holding the nut in place and using an allen key on the set screw.

Loosely tighten the other three nuts and ensure the inner frame is positioned correctly before fully tightening. The clips holding the brass frame should now be firmly fixed against the outer frame.

With the net bag now securely attached to the metal frame, the professional hand net can now be used in the field.

Replacement and related equipment

Our nylon Professional Hand Net Cover will help to protect and improve the longevity of the net, and is ideal for safe storage and transportation.

Our nylon Professional Hand Net Cover will help to protect and improve the longevity of the net, and is ideal for safe storage and transportation.

Replacements are available for the hand net fixings and the inner frame.

Extension pieces are also available for use with both the two- and three-part collapsible frames to allow for net extension. Extra joining ferrules are available too.

NHBS supplies a variety of specimen pots for storage and viewing of collected samples.

The Professional Hand Net can be found here. Our full range of professional hand and kick nets can be found here.

If you have any questions about our range or would like some advice on the right product for you then please contact us via email at customer.services@nhbs.com or phone on 01803 865913.