***** A spine-tingling debut

***** A spine-tingling debut

Leon Vlieger, NHBS Catalogue Editor

Our planet has been many different worlds over its 4.5-billion-year history. Imagining what they were like is hard – with our limited lifespan, deep time eludes us by its very nature. Otherlands, the debut of Scottish palaeontologist Thomas Halliday, presents you with a series of past worlds. Though this is a non-fiction book thoroughly grounded in fact, it is the quality of the narrative that stands out. Beyond imaginative metaphors to describe extinct lifeforms, some of his reflections on deep time, taxonomy, and evolution are simply spine-tingling.

The 16 chapters in Otherlands, each accompanied by a gorgeous illustration from Beth Zaiken, step back in time by millions or even tens of millions of years to visit a place on Earth and describe its ecosystems and organisms. Halliday includes well-known sites such as end-Cretaceous Hell Creek (66 million years ago, or mya) or Lagerstätten such as the Cambrian Chengjiang biota in China (520 mya). Far more interesting are the little-known eras and places such as the Italian promontory of Gargano during the Miocene Messinian Salinity Crisis (5.3 mya), the sweltering warmth of Seymour Island in Antarctica during the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (41 mya), or the underwater life around the Silurian Yaman-Kasy vent in Russia (435 mya).

Stylistically, Otherlands is a narrative non-fiction book. What that means is that, though everything is grounded in fact, Halliday does not get lost in the details. Where competing hypotheses exist he picks one and runs with it, rather than detailing the academic debates and different schools of thought. It is a stylistic choice that I can get behind given the quality of the writing that follows.

Because make no mistake, Halliday knows how to craft captivating prose. He won the Hugh Miller Writing Competition in 2018 and the John C. Marsden Medal from the Linnean Society for the best doctoral thesis in biology in 2016. Reading Otherlands, it is easy to see why. I do not know what they feed Scottish palaeontologists, but I was reminded of Elsa Panciroli’s Beasts Before Us. Let me back up my enthusiasm with some quotes that can only touch on a fraction of what is on offer.

There are the obvious imaginative metaphors to describe animals. The Triassic gliding reptile Sharovipteryx mirabilis (225 mya) is imagined looking rather inelegant once landed “with its membrane retracting and limbs thrown all directions like a collapsing deckchair” (p. 159), while the Ediacaran sedentary animal Dorothy’s Rope (550 mya) resembles upright towers “composed of bulges like knotted rope, as if Gaudi had designed an industrial town” (p. 277). Other descriptions are more poetic. Basilosaurids, the first fully aquatic whale ancestors in the Eocene (41 mya), have yet to evolve the melon organ. They “can listen to the music of the oceans, but they have not yet learned to sing” (p. 86).

Particularly powerful are his reflections on deep time. A recurrent theme in this book is that of impermanence: “gatherings of species in time and space may give the illusion of stability, but these communities can only last as long as the conditions that help to create them persist” (p. 18). Some ecosystems never return. The long-lived Jurassic crinoid colonies (155 mya) that made a home on floating logs blown into the sea during storms disappeared when the evolution of shipworms made “this way of life impossible, something that can and will never be replicated in quite the same way again; wood just doesn’t float for as long as it used to” (p. 151). And while the world feels old in our day, it is easy to forget the world was already old in the deep past. The mountains of the Triassic (225 mya) “are built from the deep sea”, within which can be seen “the coils and shapes of the long-extinct creatures of the Carboniferous seas, well over 100 million years old even now” (p. 158).

What made my hair stand on end were Halliday’s reflections on phylogenetics, the evolutionary relationships between animals. I love how he drowns scientific concepts in poetic language. Take the Paleocene Baioconodon (66 mya). Beyond one of the earliest placental mammals, we do not really know what it was. “Their anatomy is too non-committal, too similar to and yet too distinct from too many living orders to be placed with confidence. […] They are an unspecialised, Platonic placental, a lump of living clay from which all others are stretched, pinched and pulled into shape” (p. 105). We cannot even describe its young as kits or calves: “it does not yet make sense to talk of cattle or dogs, of monkeys or horses. None of these groups exist yet […] names lose tangibility in the depths of the past, and our language has no description for the young of common ancestors” (p. 104). You start to see why Halliday wrote his way backwards from the present. He makes a similar observation about the Ediacaran biota. Alien to us, “they are aberrant only from a modern perspective” (p. 282). Our confusion is partially because “we are trying to define them the only way we can: on the basis of those few survivors to have found paths to the present”, while the dead-end branches “by the simple fact of having not survived, forfeit a common name” (p. 283).

Similarly spine-tingling are his explanations of evolutionary processes. Species names are artificial designations for a continuous phenomenon. The way palaeontologists deal with this can be compared to rivers. Just as a river can split and its two branches be called by two names from that point in space forward, so can a species that spatially separates be called by two names from that point in time forward. And why did so many higher taxa appear during the Cambrian explosion? One idea is that, once in place, fundamentals cannot be changed easily: “evolution today can only be played within the constraints set by the past”. Another idea is that “there is nothing intrinsically impossible about a new body plan developing today, were it not for the existence of others”. Gould wrote of filling the ecological barrel and Halliday puts it thus: “establishing the basic roles within an ecosystem is like adding large rocks into a barrel […] evolutionary processes […] adding in finer and finer divisions of ecological processes, pebbles and sand falling into the barrel between the gaps left by the larger stones, structures built on other structures” (p. 258). Not only does this ring true, but it is also truly beautiful language.

Otherlands is an exceptional debut that can be savoured like a fine wine. I found myself reciting passages to anyone within earshot. Beyond a fascinating tour of extinct lifeforms, Halliday’s carefully crafted yet poetic descriptions of scientific concepts are a masterclass in spellbinding science communication.

You might also be interested in our Q&A with Otherlands author Thomas Halliday where we discuss the book and the process of writing it, our endless fascination with dinosaurs and the lessons we might learn from studies of deep time.

Wooden bat boxes

Wooden bat boxes  Woodstone and woodcrete bat boxes

Woodstone and woodcrete bat boxes Eco-plastic bat boxes

Eco-plastic bat boxes

There are also pole-mounted bat boxes (sometimes known as rocket boxes). These bat boxes are helpful alternatives in areas where there is nowhere to mount the bat box. An additional benefit is that they ensure that the bat box gains maximum sunlight in shaded areas.

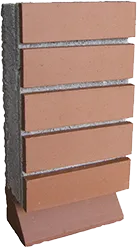

There are also pole-mounted bat boxes (sometimes known as rocket boxes). These bat boxes are helpful alternatives in areas where there is nowhere to mount the bat box. An additional benefit is that they ensure that the bat box gains maximum sunlight in shaded areas. Lastly, there are bat roost access titles and bricks. These are designed to provide bats with access points within roof or ridge tiles. Some bats will roost in the confined spaces beneath the tiles and others will use the open roof space to roost.

Lastly, there are bat roost access titles and bricks. These are designed to provide bats with access points within roof or ridge tiles. Some bats will roost in the confined spaces beneath the tiles and others will use the open roof space to roost.