A summer visitor, the common swift appears suddenly with the change in season, swooping overhead with its unmistakeable call. From their travels to Africa, to their short breeding season in the UK, swifts appear to defy gravity with their extraordinary migratory feats, with some in flight for ten months of the year. In The Screaming Sky, Charles Foster follows the swifts across the world, recounting his travels and the lives of these remarkable creatures.

A summer visitor, the common swift appears suddenly with the change in season, swooping overhead with its unmistakeable call. From their travels to Africa, to their short breeding season in the UK, swifts appear to defy gravity with their extraordinary migratory feats, with some in flight for ten months of the year. In The Screaming Sky, Charles Foster follows the swifts across the world, recounting his travels and the lives of these remarkable creatures.

Charles Foster, author of the New York Times bestseller, Being a Beast, is a writer, barrister and a Fellow of Green Templeton College, University of Oxford. With publication of his latest book due soon, Charles has very kindly agreed to answer some of our questions.

Firstly, could you tell us a little bit about your background and how you came to write The Screaming Sky?

I’m originally from Sheffield, and as a small boy I was obsessed with natural history. One summer I was sitting in a field watching and counting the house martins. Suddenly there was something else there: it was a completely different kind of creature, and it inhabited the air while other birds just visited it. I was immediately drunk on its power and its mastery and its swashbucklingness. It could have ended badly: it might have made me worship power. But (that’s another story) I was spared that fate, and instead started to wonder whether I could know anything at all about something as different from me as that. So I followed them in every way that I could: through books that taught me about their biology, through poems that taught me how impossible it is for human language to tie swifts down, by gazing up into summer skies, by playing recordings of their calls when I was missing them like crazy in the winter, and by travelling along their migration routes, hoping to catch up with them in Africa and everywhere en route. How could I not write about birds that have taught me so much about what it means to be alive?

During your travels, were there any encounters that particularly stood out for you?

Three:

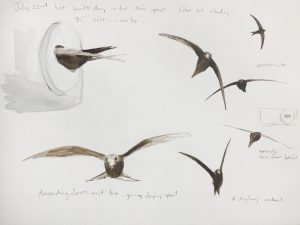

- Sitting at the foot of a tower in Greece with the swifts diving so near to my head that I could feel the air from their fluttering on my face, knowing that they were about to leave for Africa, and wondering what the bereavement would do to me.

- Sitting at the top of a tree in Oxford amongst a group of swifts which were grazing on the aerial plankton being wafted up from the ground. And seeing the grey triangular tongue of a swift as it snapped at a ballooning spider near my ear.

- Being asleep under a bush in Africa, and being suddenly awake, knowing that the swifts that I’d been searching for for so long were going to be there. And they were! It wasn’t that I’d heard them coming (swifts are generally thought to be silent in Africa). It wasn’t that I’d been told to expect them: I’d been told that we probably wouldn’t see them at all. So how did it happen? If I told you my speculations you’d think I was mad.

What were the major challenges you faced while writing your book?

I’m a fat, lumpen, middle-aged man. It’s hard to think of any organism that’s less like a swift. And, as I’ve said already, language (which is pretty inadequate at the best of times) fails particularly obviously when it comes to swifts. That’s bad news for a writer on swifts. And then there were snakes and elephants and rabid dogs and torrential diarrhoea and bush fires and soldiers and downright laziness and roads washed away and guilt at leaving the family behind.

Wildlife has suffered a substantial decline over the last few decades, and swifts have been no exception with a loss of over half of the breeding population. Has your recent experience writing The Screaming Sky left you more optimistic or more pessimistic regarding the future of the common swift?

They watched the continents shuffle to their present positions, and the mammals evolve. They’ll be screaming through the sky long after our own race has been and gone.

Do you have any new projects in the pipeline that you’d like to tell us about?

In August a book of mine called Being a Human: Adventures in Forty Thousand Years of Consciousness will be published. It’s an attempt to imagine how it would have felt to be around at three pivotal moments in the history of human consciousness: the Upper Palaeolithic (when modern consciousness ignited), the Neolithic (when we first started to see ourselves as distinct from the wild world, and started to tame ourselves and other animals), and the Enlightenment (when the universe, which had always been seen as alive, was reconceived as a machine – with disastrous consequences). And at the moment I’m writing a book called The Siege – to be published in 2022 – which is a collection of stories illustrating the challenges of living alongside you and me if you’re a wild thing with all your senses switched on.

The Screaming Sky

By: Charles Foster

Has data from the Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) you have developed been used in your books?

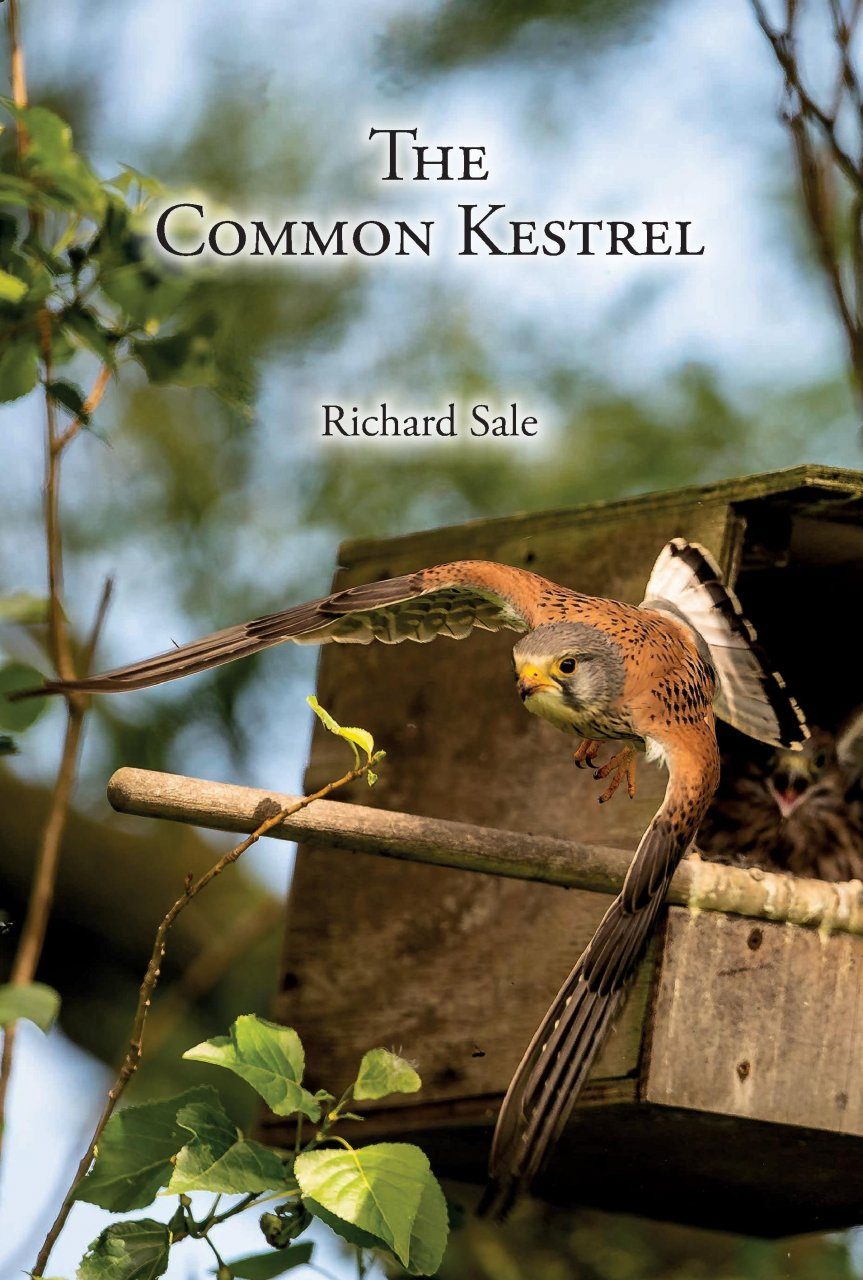

Has data from the Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) you have developed been used in your books? Why did you choose Kestrels as the subject for your latest book?

Why did you choose Kestrels as the subject for your latest book? Did you encounter any challenges collecting data for your new book: Kestrel?

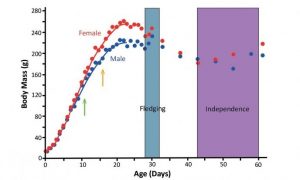

Did you encounter any challenges collecting data for your new book: Kestrel? For four successive years we set up an array of video cameras filming breeding Kestrels in a barn in Hampshire. We had one camera filming the comings and goings of the adults and, later the fledglings, and two cameras in the nest box watching egg laying, incubation, hatching and chick growth. We filmed 24 hours every day, turning on IR lights to film at night. We measured egg laying intervals to the nearest minute, found accurate hatch times and watched every prey delivery. We also set up live traps where we knew the male hunted so we could weigh the local voles and mice and estimate how many kgs of rodent it takes to make 1kg of Kestrel. The filming was interesting – over the years the adults brought in slow worms, lizards, frogs and moths, as well as voles, mice and shrews. One male also brought in a weasel. This has long been suspected, but never-before filmed.

For four successive years we set up an array of video cameras filming breeding Kestrels in a barn in Hampshire. We had one camera filming the comings and goings of the adults and, later the fledglings, and two cameras in the nest box watching egg laying, incubation, hatching and chick growth. We filmed 24 hours every day, turning on IR lights to film at night. We measured egg laying intervals to the nearest minute, found accurate hatch times and watched every prey delivery. We also set up live traps where we knew the male hunted so we could weigh the local voles and mice and estimate how many kgs of rodent it takes to make 1kg of Kestrel. The filming was interesting – over the years the adults brought in slow worms, lizards, frogs and moths, as well as voles, mice and shrews. One male also brought in a weasel. This has long been suspected, but never-before filmed.

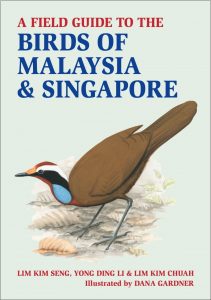

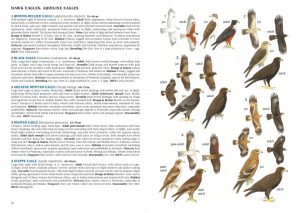

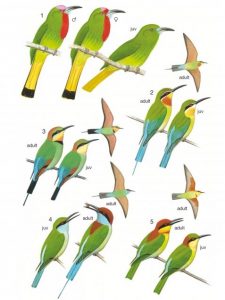

Kim Seng – My friend Dana Gardner, the illustrator of this book, got me interested in doing another book. We had successfully collaborated on a first field guide to the birds of Singapore in 1997 and were keen to work together again. Dana had a friend who was a publisher and we decided to a do a single volume field guide to the birds of the whole of Malaysia, since none existed. This was in 2010. Unfortunately, our publisher pulled out not long after that and we were left stranded. Luckily, through my fellow collaborators – Kim Chuah and Ding Li – we managed to get John Beaufoy interested in our project. A contract was signed in 2016 and as they say, the rest is history!

Kim Seng – My friend Dana Gardner, the illustrator of this book, got me interested in doing another book. We had successfully collaborated on a first field guide to the birds of Singapore in 1997 and were keen to work together again. Dana had a friend who was a publisher and we decided to a do a single volume field guide to the birds of the whole of Malaysia, since none existed. This was in 2010. Unfortunately, our publisher pulled out not long after that and we were left stranded. Luckily, through my fellow collaborators – Kim Chuah and Ding Li – we managed to get John Beaufoy interested in our project. A contract was signed in 2016 and as they say, the rest is history! Kim Seng – Each of us had different ideas on how to do the book and also other personal commitments. We as the writers also had to contend with differences in writing styles. Luckily, we decided to stick with a standard format, came up with a list of who was writing what chapters and what bird families and managed to more or less stick to our deadlines. Another challenge was the impressive work done by our illustrator. He had to do illustrations of all 829 species all by himself. To ensure accuracy, he would send us completed plates for comment, and we duly responded if changes were needed. Not an easy task, as we were based in Singapore and he, in the USA.

Kim Seng – Each of us had different ideas on how to do the book and also other personal commitments. We as the writers also had to contend with differences in writing styles. Luckily, we decided to stick with a standard format, came up with a list of who was writing what chapters and what bird families and managed to more or less stick to our deadlines. Another challenge was the impressive work done by our illustrator. He had to do illustrations of all 829 species all by himself. To ensure accuracy, he would send us completed plates for comment, and we duly responded if changes were needed. Not an easy task, as we were based in Singapore and he, in the USA. Kim Seng – Well, COVID-19 has placed tremendous restrictions on travel in both Malaysia and Singapore. You could bird in certain areas but only with social distancing and other safe practices in place. Initially, we could only look at the birds from our balconies or backyards but this was an opportunity for some of us to study some of the neglected urban birds and understand a little better. I actually published two blogs based on my observations of urban birds from my balcony! In the last couple of months, restrictions have been eased and we are allowed to go birding in our favourite birding places, but I’m still waiting for the day when I can travel freely and bird in Malaysia again.

Kim Seng – Well, COVID-19 has placed tremendous restrictions on travel in both Malaysia and Singapore. You could bird in certain areas but only with social distancing and other safe practices in place. Initially, we could only look at the birds from our balconies or backyards but this was an opportunity for some of us to study some of the neglected urban birds and understand a little better. I actually published two blogs based on my observations of urban birds from my balcony! In the last couple of months, restrictions have been eased and we are allowed to go birding in our favourite birding places, but I’m still waiting for the day when I can travel freely and bird in Malaysia again. Kim Seng – Three reasons – good birds, good food and good company. All three are never in short supply in these two amazingly friendly countries. The people are generally very friendly and the variety of local food is really incredible. Of course, the fascinating diversity of birds, with over 800 species of birds and Bornean, Peninsular and Sunda endemics in abundance are dreams to savour for birdwatchers and ornithologists alike.

Kim Seng – Three reasons – good birds, good food and good company. All three are never in short supply in these two amazingly friendly countries. The people are generally very friendly and the variety of local food is really incredible. Of course, the fascinating diversity of birds, with over 800 species of birds and Bornean, Peninsular and Sunda endemics in abundance are dreams to savour for birdwatchers and ornithologists alike.