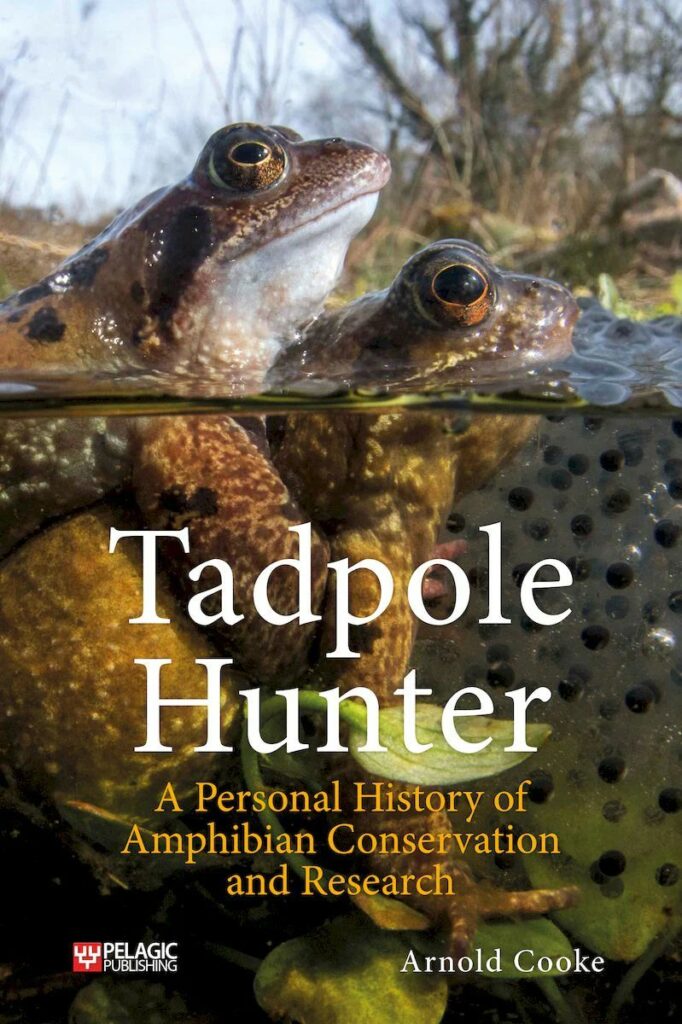

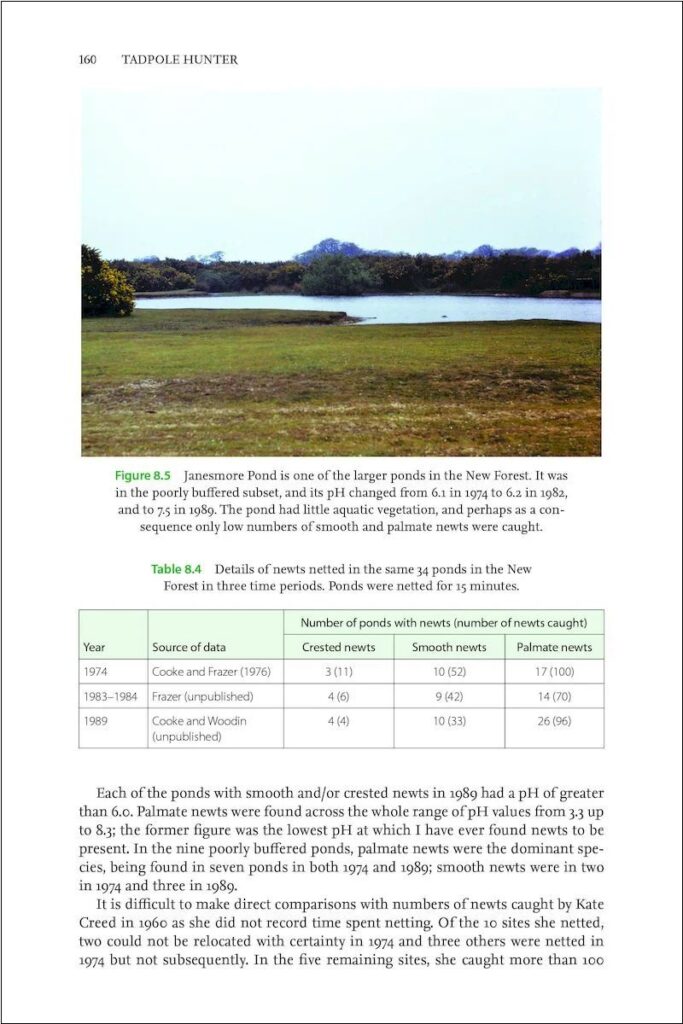

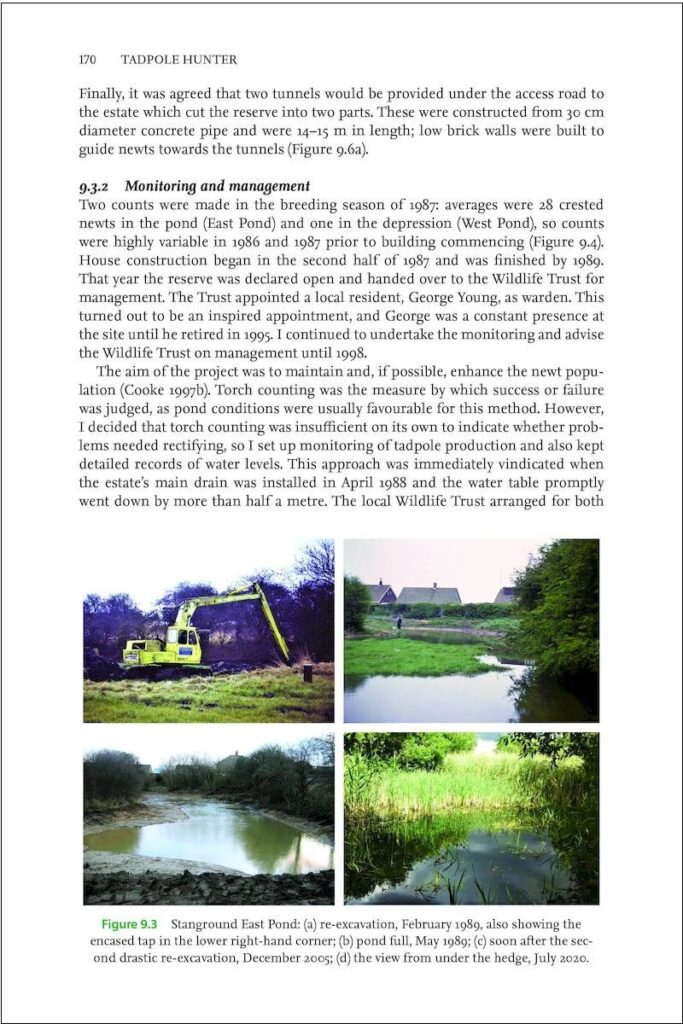

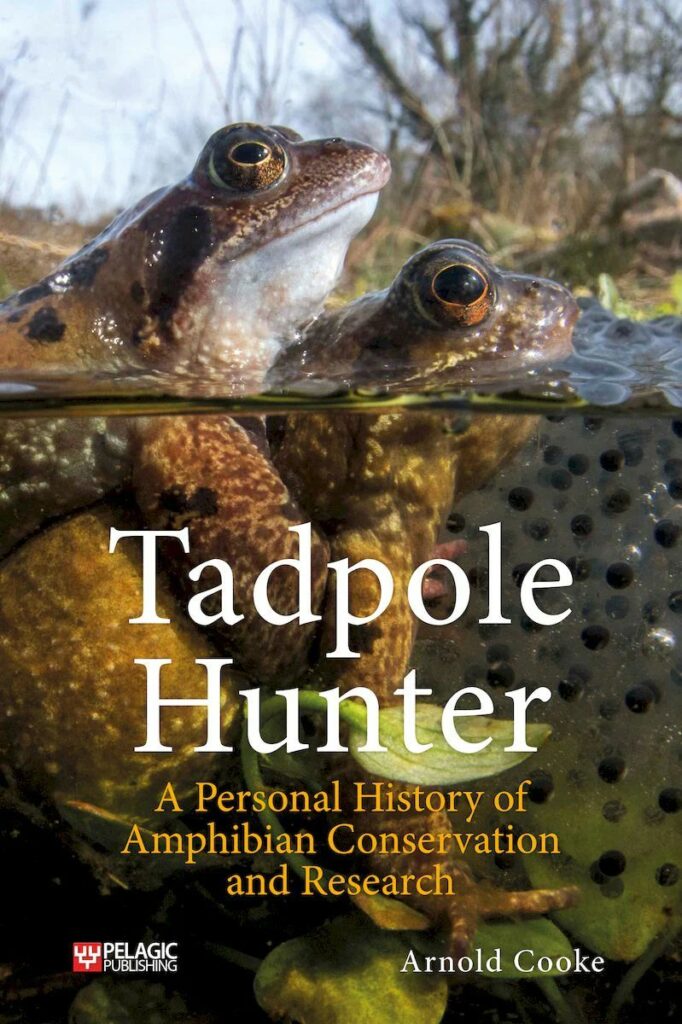

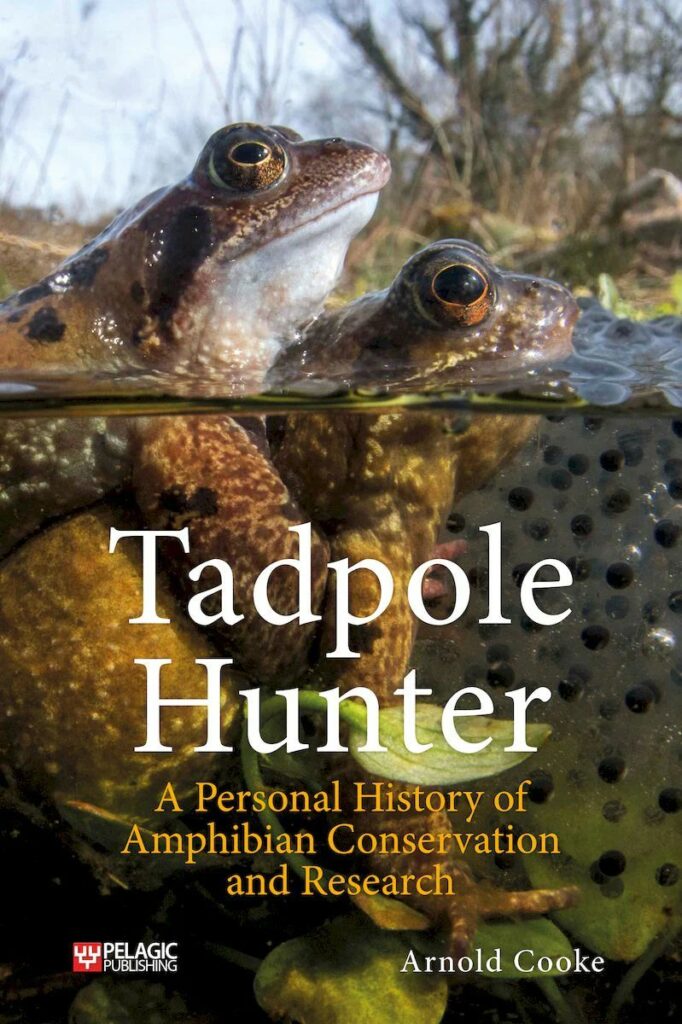

In Tadpole Hunter, author and conservationist Arnold Cooke provides us with a personal and unique insight into the history of amphibian conservation and monitoring within Britain. As well as telling the story of amphibian natural history since the 1960s, it also provides a very human perspective on how we got to where we are today and how our knowledge of amphibian populations and dynamics has progressed over the second half of the 20th century. Packed with wonderful photographs along with charts and tables representing monitoring data, this accessible book will appeal to anyone interested in amphibians and the history of conservation in Britain.

In Tadpole Hunter, author and conservationist Arnold Cooke provides us with a personal and unique insight into the history of amphibian conservation and monitoring within Britain. As well as telling the story of amphibian natural history since the 1960s, it also provides a very human perspective on how we got to where we are today and how our knowledge of amphibian populations and dynamics has progressed over the second half of the 20th century. Packed with wonderful photographs along with charts and tables representing monitoring data, this accessible book will appeal to anyone interested in amphibians and the history of conservation in Britain.

Arnold Cooke was a researcher and advisor for the the Nature Conservancy and Natural Conservation Council for 30 years. Since leaving English Nature in the late 1990s he has continued to pursue his interests in amphibians, birds and deer and has published widely on subjects as diverse as the status of Britain’s amphibians and reptiles, pollutants in birds and the environmental impacts of introduced species of deer. His previous book, Muntjac and Water Deer, was published in 2019.

Arnold Cooke was a researcher and advisor for the the Nature Conservancy and Natural Conservation Council for 30 years. Since leaving English Nature in the late 1990s he has continued to pursue his interests in amphibians, birds and deer and has published widely on subjects as diverse as the status of Britain’s amphibians and reptiles, pollutants in birds and the environmental impacts of introduced species of deer. His previous book, Muntjac and Water Deer, was published in 2019.

In this Q&A we chat with Arnold about his work with amphibians in the UK, the changes he has seen during his years working in conservation, and his hopes for the future of amphibian populations.

Although working with amphibians and their conservation has been a key part of your career, you have also dedicated a lot of your free time to recording and monitoring them and adding to the general body of knowledge regarding their populations. What is it about amphibians that you find so fascinating?

Amphibians have always appealed to me particularly because they can be relatively easy to catch – at least for vertebrates. However, they could be quite scarce where I grew up, and as a boy I was more interested in birds, flowers and invertebrates. When, in 1968, I joined the Nature Conservancy team studying the impacts of pesticides on wildlife, there were indications that frogs had declined, possibly because of pesticide use. An attraction of such a project was that there were significant gaps in knowledge about the natural history of frogs and other amphibians. This meant I had a fairly blank canvas at the beginning and I needed to undertake basic studies to try to understand what made frog populations tick, as well as doing pesticide studies. Later, I joined the Nature Conservancy Council, and became involved with conserving amphibian species nationally. By then I had started studying amphibians in a personal capacity, and was able to adapt or start local projects to inform issues of national interest, such as developing monitoring methods and investigating population stability and responses to impacts of various kinds. As information from these studies became available, it could be fed back into the system to conserve amphibians – and so helped me do my job more effectively. Once started, I became increasingly hooked and often found it difficult to stop the various strands of work.

You mention how, early in your career, you were faced with the challenge of discovering how populations of amphibians had changed in the distant and recent past and that, given the lack of empirical field data, sending questionnaires to suitable candidates was the best way to gather information about this. Do you think that conservation initiatives for amphibians are still limited by accurate population/distribution data?

You mention how, early in your career, you were faced with the challenge of discovering how populations of amphibians had changed in the distant and recent past and that, given the lack of empirical field data, sending questionnaires to suitable candidates was the best way to gather information about this. Do you think that conservation initiatives for amphibians are still limited by accurate population/distribution data?

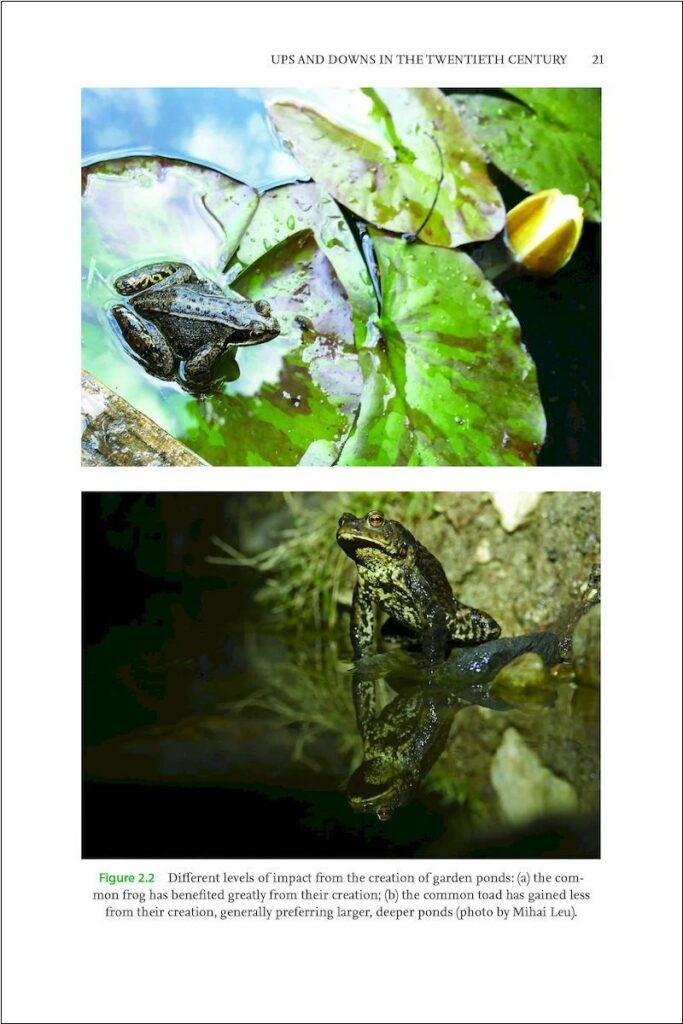

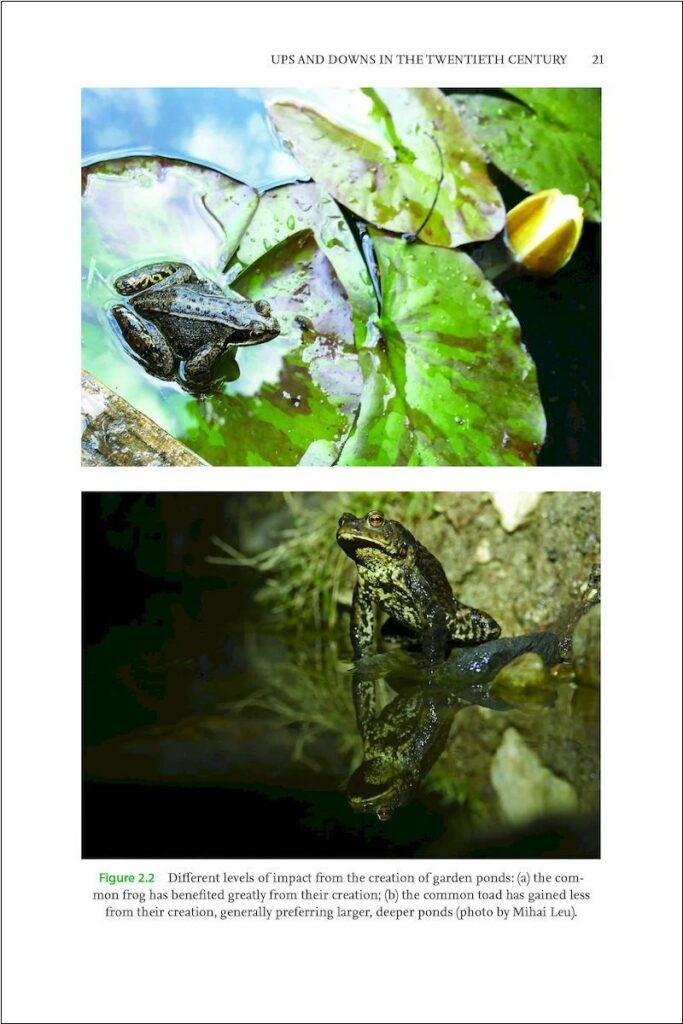

When I started to work on the common frog more than 50 years ago, there was no hard information on how the national population had changed, but several well-informed individuals considered that declines had occurred. I felt I needed to be sure that there was a problem before doing too much work on pesticides and should find out whether, where and when decreases might have occurred. I targeted those people in the British Isles who had observed frogs (and common toads) in their local ponds and this resulted in information from several hundred sites. To increase cover I asked biology teachers in schools about changes in their local populations. The consensus was that there had been widespread decreases for both species during the 1950s and 1960s. This technique had obvious flaws, but its overall conclusion seems broadly accepted. However, it is wise to acknowledge the drawbacks of the method and not to place too much credence on the resulting information, especially on reasons that might be offered for change. Where ponds were destroyed (or created) in an area, then there are tangible reasons for change. However, this is often not true for suggested contributions such as from collection, road mortality or, indeed, pesticides. Because of the population dynamics of amphibians, substantial changes occur naturally and loss of some individuals does not necessarily translate into population decline.

During later decades of the twentieth century, several similar studies were undertaken, but since the turn of the century an attempt has been made to set up a statistically sound monitoring system for the widespread amphibians and reptiles. Unfortunately, number of sites covered initially was insufficient to provide a completely satisfactory basis for the scheme to go forward in that form. Consequently some modifications and compromises were needed, and a new approach has now started. Progress is being made employing novel field, laboratory and computer methods. And I am hopeful that herpetologists can continue to tap into citizen science projects on other animal groups, particularly birds, where huge numbers of competent individuals might be organised to gather additional data on amphibians.

I should also say that knowledge of the much rarer natterjack toad is exceptionally good. All known colonies are recorded regularly, and some have been monitored continuously for 50 years. This has allowed fine tuning of conservation action at specific sites and more broadly. And the very rare pool frog receives constant attention at its introduction sites.

As someone that worked at the forefront of conservation for many decades and has seen a huge number of changes, both in the natural world and in the human organisations and councils that are charged with protecting them, are you broadly hopeful for the future of British wildlife?

As someone that worked at the forefront of conservation for many decades and has seen a huge number of changes, both in the natural world and in the human organisations and councils that are charged with protecting them, are you broadly hopeful for the future of British wildlife?

Thank you for the compliment, but I’m not sure how long I’ve spent at the ‘forefront of conservation’ – especially during the last 25 years when I’ve deliberately busied and buried myself in the detail of my own interests. Throughout my life, I’ve worked as a specialist in a range of disparate areas, rather than as a rounded generalist, so I’ve tended to focus on specific issues within the broad spectrum of wildlife conservation.

It’s true, however, that I’ve seen huge changes over the last 55 years. Some changes are of great concern – no one 50 years ago saw global warming coming. I remember there was talk about 40 years ago of the possibility of another ice age being just round the corner. The changes in biodiversity over that time have of course mainly been losses. On the other hand, there have been other types of change providing hope that British wildlife does have a reasonable future. I am thinking, for instance, of the numbers of professional people and volunteers now involved in conservation, the knowledge that has accrued, the conservation methods that have been shown to work and the legislation that has been passed. I’m aware that successive governments haven’t necessarily dealt kindly with environmental issues (or conservationists), but many peoples’ attitudes have changed markedly and younger generations are especially concerned about the environment. Just as conservationists in the past achieved more than might be expected because of their dedication, so should conservationists of the future – and there will be many more of them.

The wildlife communities and their distribution will, though, probably look very different in the future. I have lived for 55 years on the edge of the Cambridgeshire Fens. That area doesn’t sound very promising for wildlife, but I was pleasantly surprised to discover in 1968 that there were several nature reserves within easy reach including three important National Nature Reserves. However, I soon realised that reserves were like currants in a cake, there being very little of interest between them. When my wife and I drove to Norfolk to visit three other NNRs, we only managed to find one of them, despite knowing their grid references – and we had to negotiate a barbed wire fence to get into that. A permit was required for access in those days. The situation is of course very different now: visitors are generally welcomed. And reserves are increasingly being connected up, as is occurring in my area with two of the NNRs. I don’t doubt that much of our biodiversity will in future be experienced inside landscape-sized areas. I just hope it works. I regret that kids today don’t have the freedom that I had to explore and find things out for myself. Presumably, however, accessibility of knowledge will continue to increase. No need for children to learn and remember much, just use the phone app. Not wishing to be too cynical, surely enough youngsters will be captivated to become the dedicated conservationists of the future?

As regards amphibians, I believe we have more or less stopped the declines of the twentieth century and recoveries have started for some species. The future is uncertain but there are reasons to be hopeful.

Your working life has been incredibly fascinating and varied. Are there any parts of it that you remember with particular fondness or that stand out in your memory?

Your working life has been incredibly fascinating and varied. Are there any parts of it that you remember with particular fondness or that stand out in your memory?

I’ve been very lucky with what I’ve been allowed or managed to do during my working life of more than 60 years – that’s using the word ‘working’ very loosely. I still have a reasonably good grasp of what I did and when I did it because I’ve usually written up (but not necessarily published) my observations and thoughts in some form or other. When I’ve been able to study wildlife, there has been very little that I haven’t enjoyed. There have been stand-out moments such as: in 1962 when I found my observations demonstrated that birds in suburbia were more approachable than those in the countryside; in 1982 when I watched breeding newts by torchlight for the first time; and in 1994 when I realised I could put out tempting vegetation for muntjac in a wood and find it had been consumed by the following morning. Each of these moments led to the development of field monitoring techniques.

Then there have also been periods that have been memorable for different reasons. The five years 1968-1973 with the old Nature Conservancy at Monks Wood were marked by an extraordinary level of interest in our work shown by the public, politicians and even royalty. In contrast, the last couple of decades have been spent quietly at home pottering around doing as much fieldwork as possible and sorting out what results meant. My qualifications are in chemistry and biochemistry and, had things turned out differently, I might have been more of a lab worker. But working outside has always been my preference. When working for English Nature in the 1990s, we were required to fill in risk assessment forms when away from the office, including when working outside normal office hours. Some years, I filled in nearly 200 such forms, revealing how much fieldwork I did as well as providing an illustration of why I was glad to leave behind modern management methods in the late 1990s.

What would be the main message you would give to the conservationists and ecologists that are following in your footsteps?

Because of my rather blinkered working experience during the current century, I think the most appropriate message is simply to say, ‘good luck and thank you’. Everyone needs some luck in order to have a satisfying career and I genuinely appreciate what present and future generations are doing and will continue to do to help understand and conserve wildlife.

Finally, what is occupying your time at the moment? Do you have plans for further books?

My main task this year has probably been seeing Tadpole Hunter to fruition, so it’s good to have it published at last. I’d wanted to review some of the topics in the book for many years, but they’ve only appeared in book form because of the Covid pandemic. My wife and I needed to shield during the lockdowns, so I started to review a couple of subject areas in March 2020. Later that summer, I realised that I had the basis for a book, so roughed it out and continued writing. I don’t intend writing another book, in part because of the time commitment. While writing Tadpole Hunter, I published several items on deer and have vague plans for other articles once the dust has settled from the book.

I have occasionally tinkered with bird behaviour in a very simple way and may revisit data collected in the 1980s. Earlier this year, I was surprised and very pleased to be invited to contribute my historic data to a global database of avian ‘flight initiation distances’, which precipitated a dive into material I hadn’t looked at for many years. Another line I might pursue concerns citizen science. I’ve participated in a number of such projects over the years, recording birds in particular, but also mammals and trees. At the moment, I’m interested in what an individual participant could get out of it? If repeated annually, it can provide useful monitoring information on species at your location. In some instances, I have carried on recording for long after the citizen science project finished.

Although I’m now doing very little fieldwork, I still have ideas to explore, but I’m sure there won’t be another book unless……….

Tadpole Hunter: A Personal History of Amphibian Conservation and Research was published by Pelagic Publishing in August 2023 and is available from nhbs.com

Arnold Cooke was a researcher and advisor for the the Nature Conservancy and Natural Conservation Council for 30 years. Since leaving English Nature in the late 1990s he has continued to pursue his interests in amphibians, birds and deer and has published widely on subjects as diverse as the status of Britain’s amphibians and reptiles, pollutants in birds and the environmental impacts of introduced species of deer. His previous book,

Arnold Cooke was a researcher and advisor for the the Nature Conservancy and Natural Conservation Council for 30 years. Since leaving English Nature in the late 1990s he has continued to pursue his interests in amphibians, birds and deer and has published widely on subjects as diverse as the status of Britain’s amphibians and reptiles, pollutants in birds and the environmental impacts of introduced species of deer. His previous book,

Helen Read is a Conservation Officer for the City of London Corporation based at Burnham Beeches, a post held for over 30 years. She has written numerous books and papers on a variety of subjects, the majority being on the management of veteran trees and topics relating to invertebrates. She has also been an active committee member in various invertebrate societies.

Helen Read is a Conservation Officer for the City of London Corporation based at Burnham Beeches, a post held for over 30 years. She has written numerous books and papers on a variety of subjects, the majority being on the management of veteran trees and topics relating to invertebrates. She has also been an active committee member in various invertebrate societies.

RHS The Little Book of Wild Gardening

RHS The Little Book of Wild Gardening Gardening for Bumblebees

Gardening for Bumblebees