Professor Jeff Ollerton is a researcher, educator, consultant and author, specialising in mutualistic ecological relationships – in particular, those between plants and their pollinators. Now one of the world’s leading experts on pollinators and pollination, he has conducted field research in the UK, Australia, Africa, and Tenerife, and published a huge body of ground-breaking research which is highly-cited and used at both national and international levels to inform conservation efforts. Jeff currently holds Visiting Professor positions at the University of Northampton in the UK and Kunming Institute of Botany in China.

Professor Jeff Ollerton is a researcher, educator, consultant and author, specialising in mutualistic ecological relationships – in particular, those between plants and their pollinators. Now one of the world’s leading experts on pollinators and pollination, he has conducted field research in the UK, Australia, Africa, and Tenerife, and published a huge body of ground-breaking research which is highly-cited and used at both national and international levels to inform conservation efforts. Jeff currently holds Visiting Professor positions at the University of Northampton in the UK and Kunming Institute of Botany in China.

His recent book, Pollinators & Pollination: Nature and Society, provides a hugely informative yet accessible look at the ecology and evolution of pollinators around the globe, and discusses their conservation in a world that seems to be stacked against them.

In this article we chat with Jeff about his background, the book and the future of pollinators in an increasingly changing climate.

Firstly, could you tell us a little bit about your background and how you came to write Pollinators & Pollination: Nature and Society?

Where to begin? Like lots of ecologists my interest started with natural history as a kid: poking around in rock pools, looking under stones, keeping tadpoles in jars, collecting fossils, the usual stuff that most people grow out of. I was born in Sunderland, close to the shipyards and coal mines that provided employment for most of my family. The grasslands and scrubby areas that developed on bombsites and after slum clearance were where I ranged free: my wildlife playground was the result of industrial development and decline. I also learned a lot from my dad who was a keen gardener, and plants have always been a passion. At school I didn’t do well – “easily distracted” said my reports – and only passed one A level (Biology). That was enough to get me into an HND in Applied Biology at Sunderland Polytechnic, then onto the second year of a BSc Environmental Biology degree at Oxford Polytechnic. My dissertation supervisor was Andrew Lack and he convinced me that I should apply for a PhD with him, looking at the pollination ecology, flowering phenology, and reproductive output of grassland plants in colonising and established grasslands. That was completed in 1993 (by which time the institution was Oxford Brookes University) and I went off to do some travelling and field work in Australia, funded by some small grants. When I got back I applied for numerous postdoctoral positions but the first job I was offered was a lectureship at Nene College of Higher Education in Northampton. At the time it was predominantly a teaching institution but they were keen to develop their ecological research. I originally planned to be there for a couple of years and ended up staying for 25! By that time it had transitioned into the University of Northampton. Throughout all of this the main focus of my research has been the ecology, evolution and conservation of plant-pollinator interactions, with field work in the UK, Africa, South America, and Asia. That’s a huge field of study, ranging in scope from molecular ecology to animal behaviour to agriculture and government environmental policy. A few years ago it struck me that there was a need to bring together these different strands into a single, coherent book that presented a state of the art account of why all of this was important, how the different topics fitted together, what we had learned so far after a couple of hundred years of research, and where the gaps and scientific disagreements lay. The result was Pollinators & Pollination: Nature and Society.

While it’s evident that habitat destruction and fragmentation have a huge role to play in the decline of pollinator species, you also state that rising temperatures may be a more significant factor, particularly for species such as bumblebees. Given the continual, and some may say unstoppable, rise in global temperatures, are you hopeful in any way for the future of pollinators?

While it’s evident that habitat destruction and fragmentation have a huge role to play in the decline of pollinator species, you also state that rising temperatures may be a more significant factor, particularly for species such as bumblebees. Given the continual, and some may say unstoppable, rise in global temperatures, are you hopeful in any way for the future of pollinators?

Well, first of all, I certainly don’t think that climate change is unstoppable. We know what needs to be done and we know how to do it, though it’s not easy of course. But, yes, we are already seeing the effects of climate change on pollinators, particularly in relation to range shifts as insects move northwards in the northern hemisphere. Bumblebees are a particular concern because on the whole they are adapted to colder temperatures. However most other bees are adapted to warmer, drier conditions, and they may benefit from moderate climate change. The problem is that we simply don’t know enough about the natural histories of most of the 20,000 or so species of bees to say. Our knowledge of most of the hundreds of thousands of other species of pollinators is even less well developed. But I do have some optimism that pollination services to most plant species will be maintained under moderate climate change because we know from experimental work that we’ve carried out that the majority of interactions are relatively generalised and interchangeable: a range of pollinators can pollinate most plants, and vice versa. It’s the more specialised interactions that are likely to be less robust to climate change, especially in places like South Africa where I have been fortunate to work. The key to conserving pollinators, as it is for all biodiversity, is creation, restoration, linking-up, and protection, of natural habitats. As I argue in the book, we have to go far beyond “planting for pollinators” and putting up a few bee hotels if we are serious about conserving pollinators in our rapidly changing world.

While professional scientific research, alongside informed policy change, will obviously be key in directing the future of pollinators around the world, you also mention the importance of amateur naturalists and citizen scientists in collecting data and providing some of the legwork behind sustained long-term studies. What advice would you give to a non-professional individual who wishes to get involved with pollinator conservation? (eg. volunteering, donating to charities/organisations, lobbying for policy change etc.)

While professional scientific research, alongside informed policy change, will obviously be key in directing the future of pollinators around the world, you also mention the importance of amateur naturalists and citizen scientists in collecting data and providing some of the legwork behind sustained long-term studies. What advice would you give to a non-professional individual who wishes to get involved with pollinator conservation? (eg. volunteering, donating to charities/organisations, lobbying for policy change etc.)

Yes, all of what you list there is important, and I would add that individuals can do a lot by thinking carefully about what they plant in their gardens and how they manage them (i.e. not using pesticides) and lobbying local councils about how parks and road verges are managed. They could also get involved in initiatives such as the UK Pollinators Monitoring Scheme. Similar schemes have been set up in other countries. Adding observations to iRecord is also important.

When hearing about the decline of pollinators, many people (fuelled by frequent media stories) will immediately be fearful about the future and security of our food production. Is there a valid reason for concern, and are there any precautionary steps that you believe the agricultural industry should be taking to deal with a potential collapse in pollinators?

First of all, I don’t think that pollinators are going to disappear from agricultural landscapes completely, that’s hugely unlikely. But there are a couple of things that should concern farmers and governments. There’s growing evidence that the yields of some crops, in some places, are limited by availability of pollinators, and that’s likely to get worse if pollinator populations decline. We also know that there are crops which, although they can self-pollinate, produce a higher quality of fruit or seeds if they are outcrossed by pollinators. So there’s a clear financial benefit for farmers to take pollinator declines seriously. Globally, most of the staple crops are either wind pollinated grasses (rice, wheat, etc.) or are propagated by tubers (potatoes, yams) so food security in terms of populations starving is unlikely to be a consequence of pollinator decline. However most of the fruit and vegetables that provide the essential vitamins and minerals in our diets need pollinators either for the consumed crop or, as in the case of onions, for the seeds that produce the crop. So food security in the sense of having a healthy diet is definitely something that we should take seriously. Things that farmers and the agricultural industry should be doing include the obvious such as restoring and creating natural habitat on their farms, not over-managing grasslands and hedgerows, and reducing the amount of biocides that they are using.

I discovered lots of interesting things from your book that I previously didn’t know – such as the fact that there are pollinating lizards! In all of your years of study, what is the most fascinating fact that you have learned about pollinators?

I discovered lots of interesting things from your book that I previously didn’t know – such as the fact that there are pollinating lizards! In all of your years of study, what is the most fascinating fact that you have learned about pollinators?

Oh, wow, that’s a tough one! Every research project that I’ve undertaken has turned up new information and observations that have intrigued and excited me, and even blown my mind. That’s one of the reasons why I do what I do, there’s so much still to discover. I estimate that we’ve got some kind of information about the pollinators of only about 10% of the 352,000 species of flowering plants that there are in the world. Even in Britain and Ireland the reproductive ecologies of most of the plants have hardly been studied. So there are always new things to discover. Citing a single fascinating fact is difficult, but if I had to choose one it would be the calculation that I made for a review article in 2017 when I worked out that as many as 1 in 10 insect and vertebrate species may visit flowers as pollinators. That did astound me and I had to double check my maths!

2020 was a year that was largely dominated by the Covid-19 crisis, a fact that you touch on briefly in your book. How has the pandemic affected your working life and, as a researcher who relies on time spent in the field, how have you dealt with the challenges of lockdown and restricted movement?

Ughh, yes, it’s been difficult. I was supposed to take a group of students to Tenerife in April for our annual field course and that had to be cancelled. It’s the first year since 2003 that I’ve not made the trip and it curtailed some long-term data collection that I’ve been undertaking. Perhaps the universe is telling me that it’s time to publish the data….? But on the plus side, once we knew that we’d be in lockdown for some months, I sent out an email to my network of pollination ecologists to suggest that we use the time to collect data on flower-pollinator interactions in our gardens. The response was phenomenal! It’s generated over 20,000 observations from all over the world. We’re writing up a paper describing the data set at the moment and we will make it freely available to PhD and early career researchers who were not able to collect data last year and whose funding and time are limited.

Finally, what are you working on currently, and do you have plans for further books?

Finally, what are you working on currently, and do you have plans for further books?

So back in October I stepped down from my full-time professorship to work independently as a consultant ecological scientist and author – my new website has just gone live in fact: www.jeffollerton.co.uk. Although I will miss teaching students, I really needed some new challenges and wanted to work more closely at the conservation and advisory end of the field, and start to make more of a difference on the ground. I still have a Visiting Professorship at Northampton where I’m completing some externally funded projects and supervising a couple of PhD researchers. And I’ve recently been appointed Visiting Professor at the Kunming Institute of Botany in China where, vaccines willing, I will be spending part of the summer on a climate change and pollinators project. As for further books, yes, there are another three that I want to complete in the next few years. I’m talking with Pelagic at the moment about the next one and they are interested, but I’d like to keep the topic hush-hush for now – I’m referring to it as “Project B”! But it does deal with pollination, I can tell you that.

From the Sunday Times bestselling author of

From the Sunday Times bestselling author of

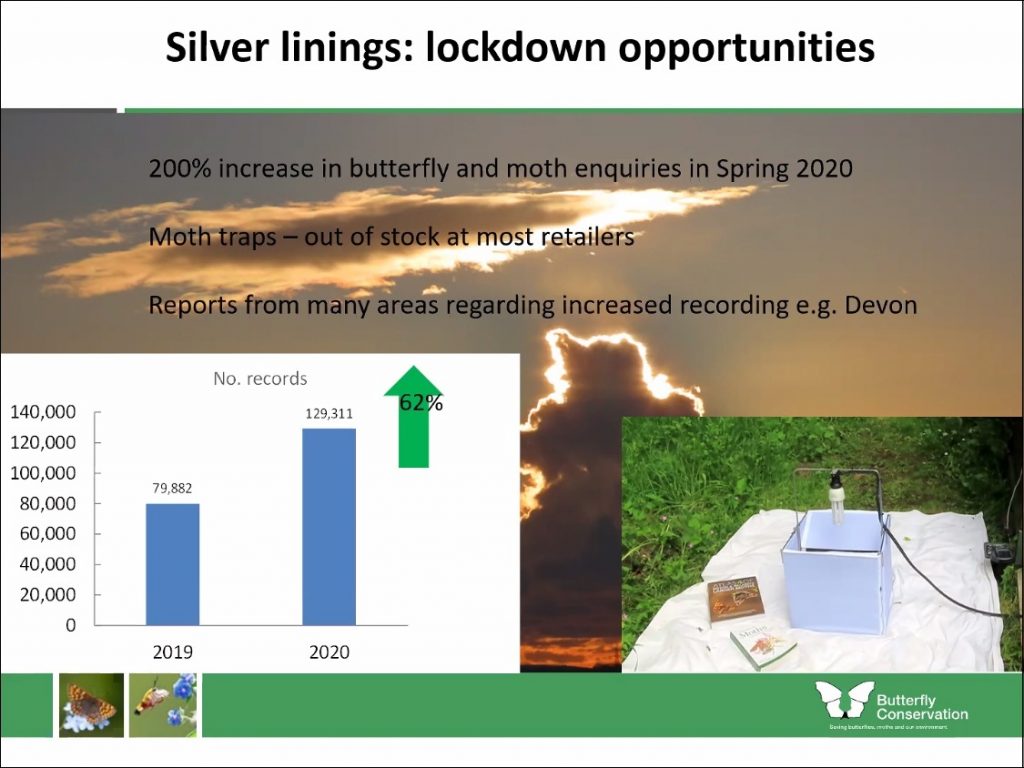

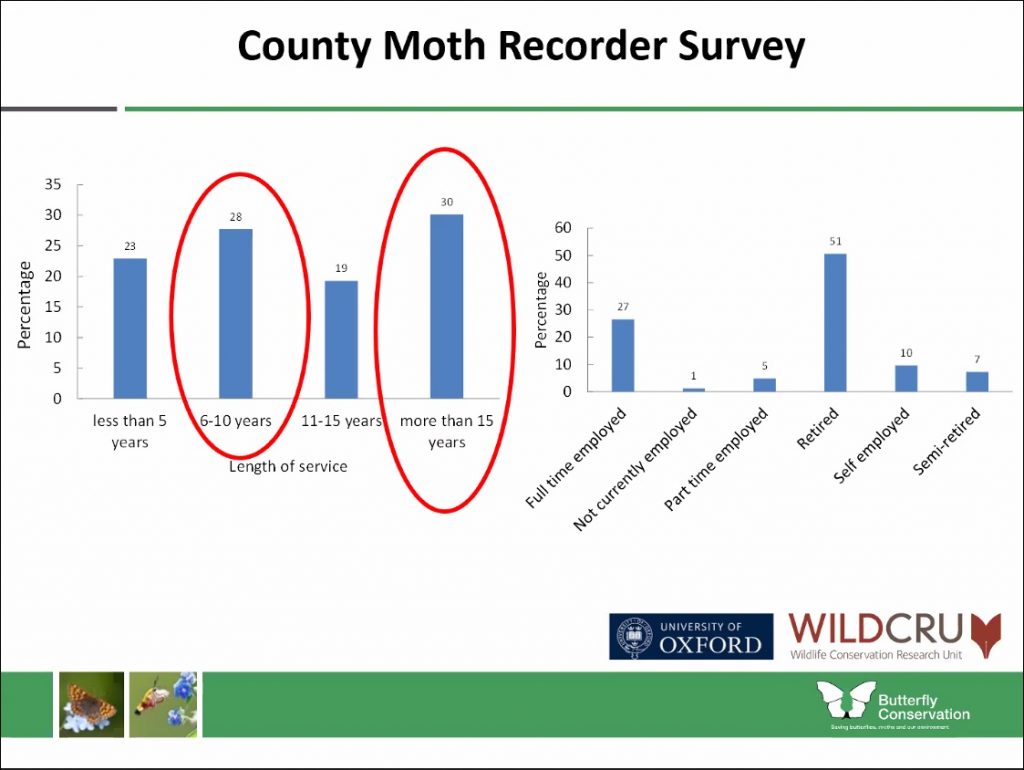

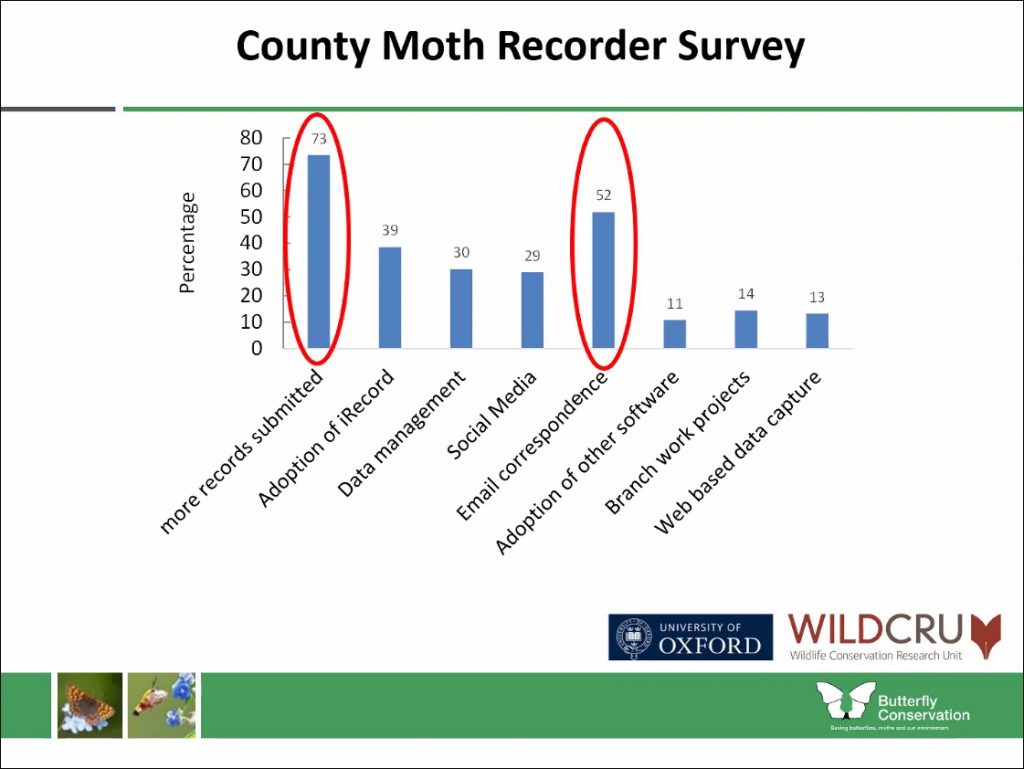

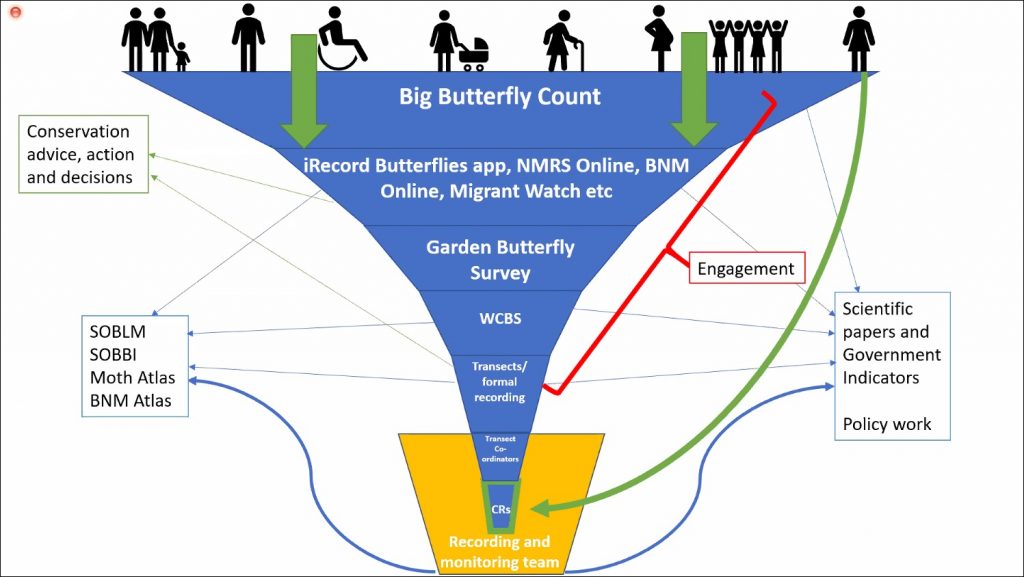

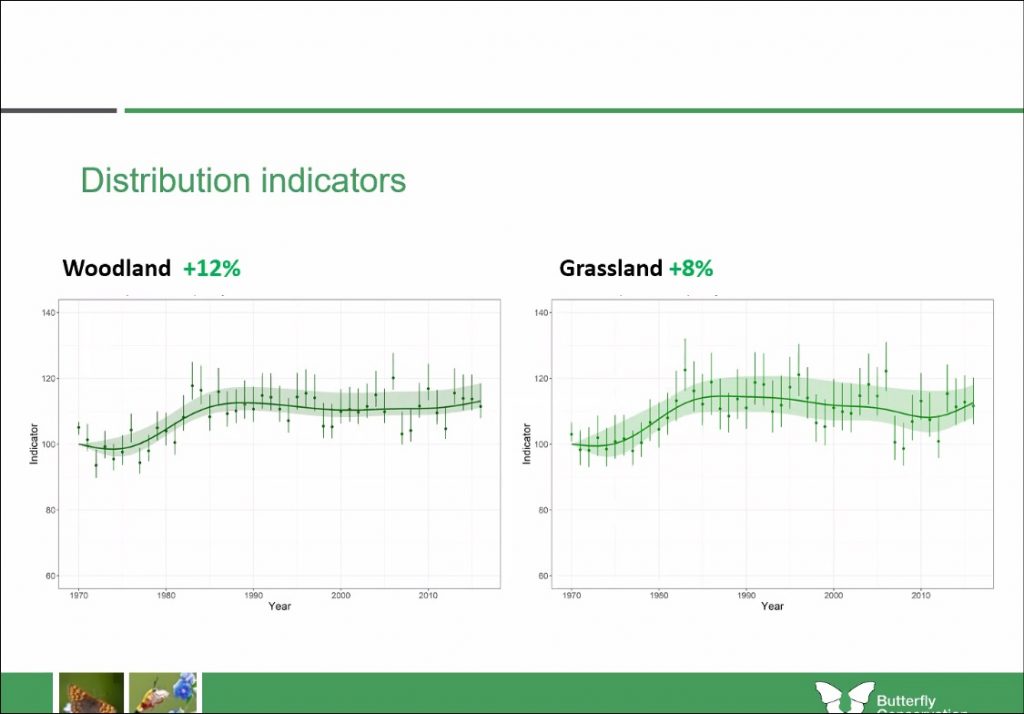

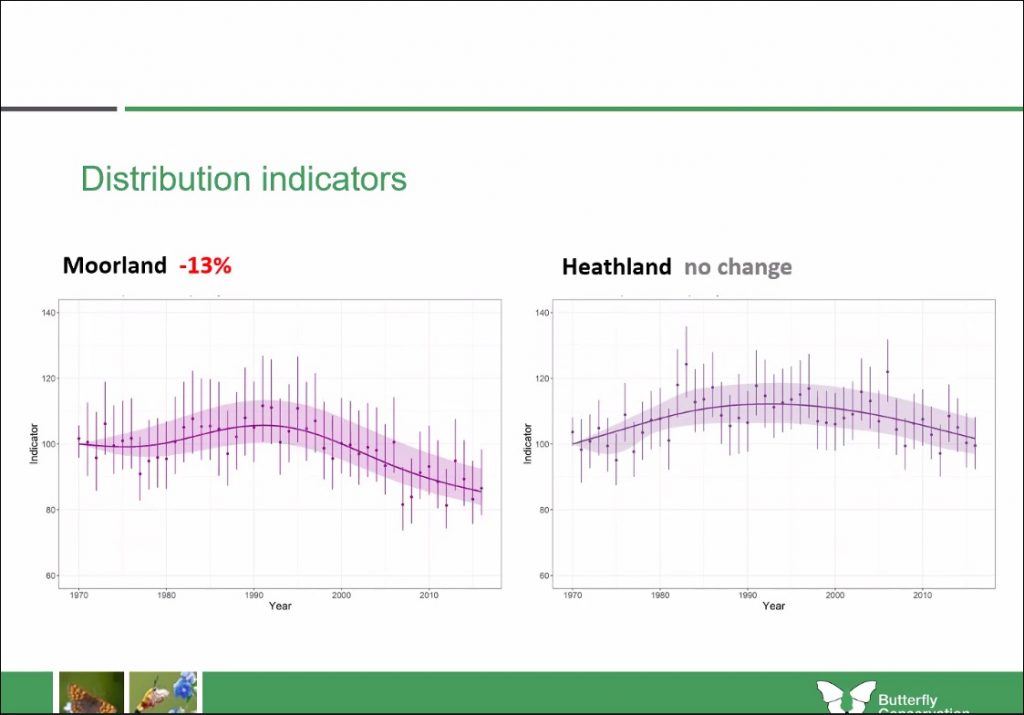

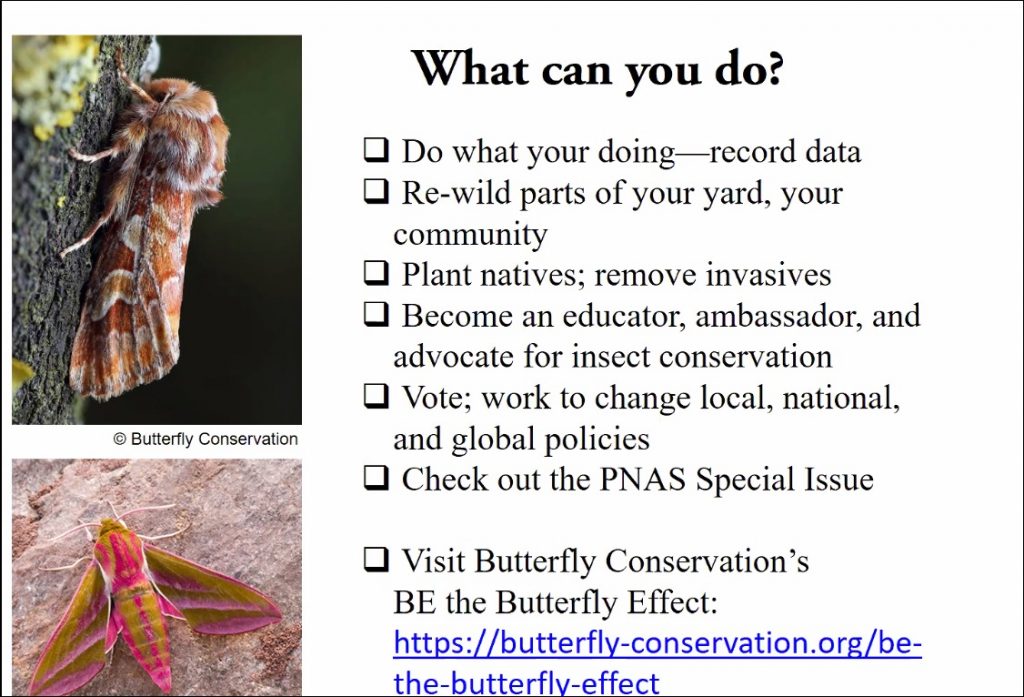

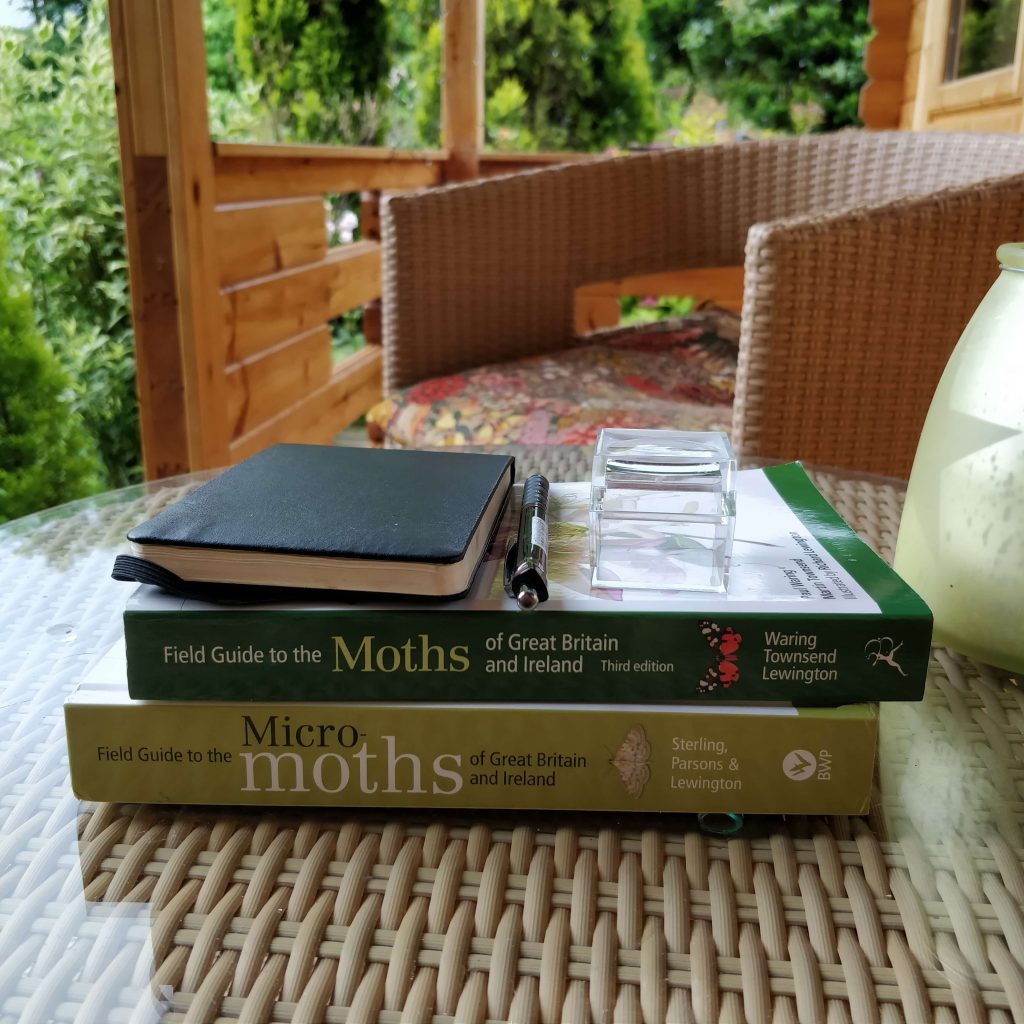

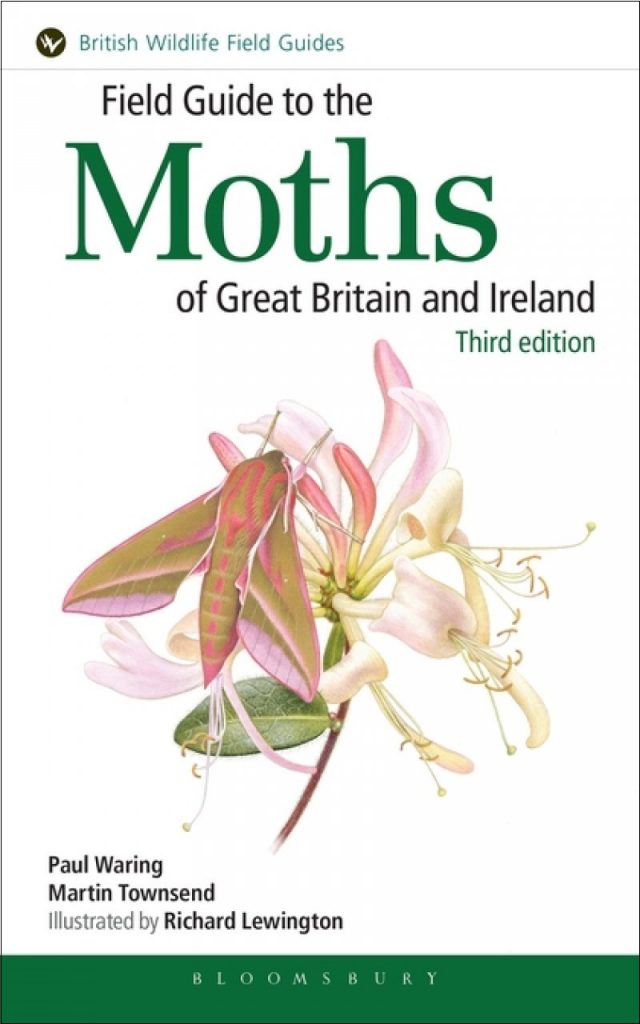

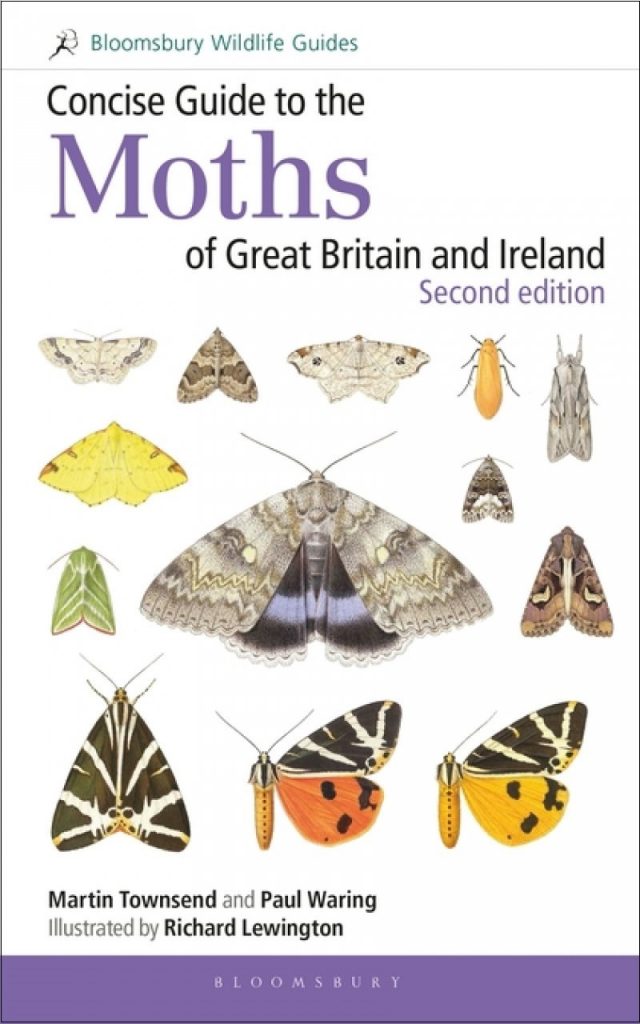

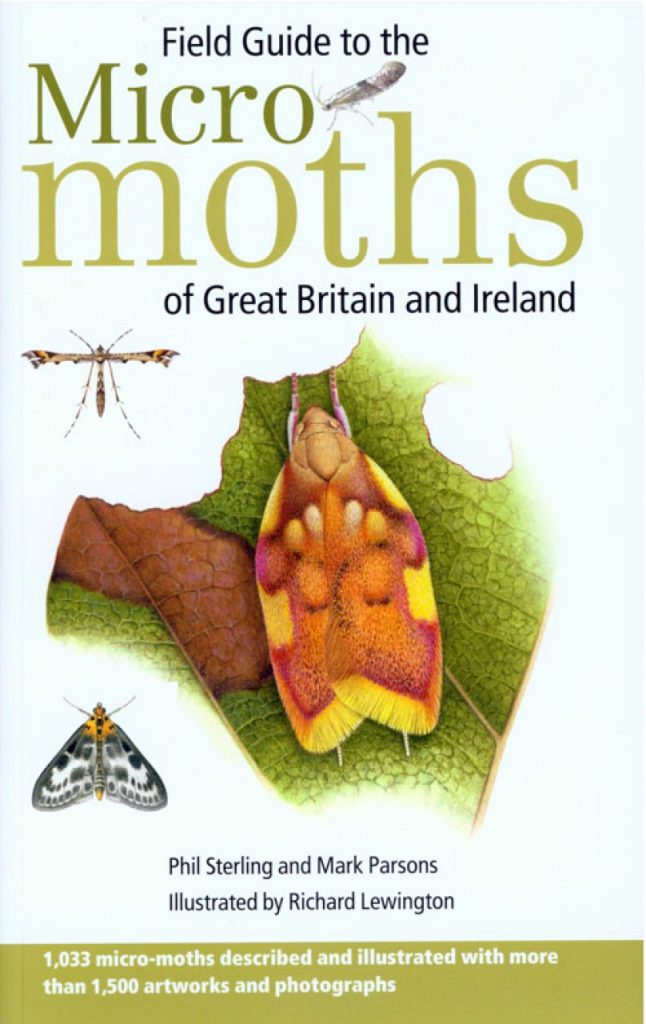

Katie spoke about the benefits of this widening pool of public participation suggesting that, not only does it expand our understanding of national biodiversity, but it also connects us meaningfully with wildlife and has positive effects on our own personal wellbeing. Public perception of moths and butterflies is improving through events like Butterfly Conservation’s Big Butterfly Count, which encourages people to log the species they see in their local patch for a set period of time using a dedicated app. The wealth of sightings that come through apps like this and iRecord – alongside information gathered from social media and anecdotal sources – has meant that the recording process is a vast and time consuming activity for volunteers. Katie spoke on how this process currently works and speculated on how it might be streamlined moving forwards.

Katie spoke about the benefits of this widening pool of public participation suggesting that, not only does it expand our understanding of national biodiversity, but it also connects us meaningfully with wildlife and has positive effects on our own personal wellbeing. Public perception of moths and butterflies is improving through events like Butterfly Conservation’s Big Butterfly Count, which encourages people to log the species they see in their local patch for a set period of time using a dedicated app. The wealth of sightings that come through apps like this and iRecord – alongside information gathered from social media and anecdotal sources – has meant that the recording process is a vast and time consuming activity for volunteers. Katie spoke on how this process currently works and speculated on how it might be streamlined moving forwards.

The compilation of data for the new

The compilation of data for the new

Professor Jeff Ollerton is a researcher, educator, consultant and author, specialising in mutualistic ecological relationships – in particular, those between plants and their pollinators. Now one of the world’s leading experts on pollinators and pollination, he has conducted field research in the UK, Australia, Africa, and Tenerife, and published a huge body of ground-breaking research which is highly-cited and used at both national and international levels to inform conservation efforts. Jeff currently holds Visiting Professor positions at the University of Northampton in the UK and Kunming Institute of Botany in China.

Professor Jeff Ollerton is a researcher, educator, consultant and author, specialising in mutualistic ecological relationships – in particular, those between plants and their pollinators. Now one of the world’s leading experts on pollinators and pollination, he has conducted field research in the UK, Australia, Africa, and Tenerife, and published a huge body of ground-breaking research which is highly-cited and used at both national and international levels to inform conservation efforts. Jeff currently holds Visiting Professor positions at the University of Northampton in the UK and Kunming Institute of Botany in China.

While professional scientific research, alongside informed policy change, will obviously be key in directing the future of pollinators around the world, you also mention the importance of amateur naturalists and citizen scientists in collecting data and providing some of the legwork behind sustained long-term studies. What advice would you give to a non-professional individual who wishes to get involved with pollinator conservation? (eg. volunteering, donating to charities/organisations, lobbying for policy change etc.)

While professional scientific research, alongside informed policy change, will obviously be key in directing the future of pollinators around the world, you also mention the importance of amateur naturalists and citizen scientists in collecting data and providing some of the legwork behind sustained long-term studies. What advice would you give to a non-professional individual who wishes to get involved with pollinator conservation? (eg. volunteering, donating to charities/organisations, lobbying for policy change etc.) I discovered lots of interesting things from your book that I previously didn’t know – such as the fact that there are pollinating lizards! In all of your years of study, what is the most fascinating fact that you have learned about pollinators?

I discovered lots of interesting things from your book that I previously didn’t know – such as the fact that there are pollinating lizards! In all of your years of study, what is the most fascinating fact that you have learned about pollinators? Finally, what are you working on currently, and do you have plans for further books?

Finally, what are you working on currently, and do you have plans for further books?

After two decades of researching them, has your own attitude towards them changed?

After two decades of researching them, has your own attitude towards them changed? You mention many people seem to think adult flies lack brains, this misconception being fuelled by watching them fly into windows again and again. This may seem like a very mundane question but why, indeed, do they do this?

You mention many people seem to think adult flies lack brains, this misconception being fuelled by watching them fly into windows again and again. This may seem like a very mundane question but why, indeed, do they do this? You explain how insect taxonomists use morphological details such as the position and numbers of hairs on their body to define species. I have not been involved in this sort of work myself, but I have always wondered, how stable are such characters? And on how many samples do you base your decisions before you decide they are robust and useful traits? Is there a risk of over-inflating species count because of variation in traits?

You explain how insect taxonomists use morphological details such as the position and numbers of hairs on their body to define species. I have not been involved in this sort of work myself, but I have always wondered, how stable are such characters? And on how many samples do you base your decisions before you decide they are robust and useful traits? Is there a risk of over-inflating species count because of variation in traits?

Bumblebees: An Introduction

Bumblebees: An Introduction