James Lowen is an award-winning writer whose work is regularly featured in The Telegraph, BBC Wildlife and Nature’s Home, among other publications. He is also an editor, lecturer, consultant and keen photographer.

James Lowen is an award-winning writer whose work is regularly featured in The Telegraph, BBC Wildlife and Nature’s Home, among other publications. He is also an editor, lecturer, consultant and keen photographer.

From hiking up mountains, to checking his garden moth-trap with his daughter, Much Ado About Mothing is a wonderfully written, engaging account of James’ travels in search of Britain’s rarest and most remarkable moths. James has kindly agreed to answer some of our questions about his latest book below.

Could you tell us a little bit about your background and how you came to write Much Ado About Mothing?

I’m a Norfolk-based naturalist and author who has written 12 books, all broadly sitting in the nexus of wildlife, travel and conservation. Two of those books: A Summer of British Wildlife and 52 European Wildlife Weekends, won Travel Guidebook of the Year awards, which was most pleasing and inspired me to both attempt some longer-form writing (Much Ado About Mothing is fundamentally a travel narrative – an exploration of Britain) and take on a more ‘challenging’ topic. And what could be more challenging than championing the very animals (moths) that the general public purports to hate?

I could readily understand where so many people were coming from in harbouring disdain for moths. For decades, I was also virulently anti-moth, (pre)judging them as uninteresting and usually irritating little brown jobs that remained invisible yet destroyed my suits. However, when a friend showed me a Poplar Hawk-moth, I remember the date precisely: 7 July 2012, my world changed forever. Wrapped in silver and grizzled with iron filings, this sweetly furry being opened my eyes, brought me to my senses and revolutionised the way that I engage with nature. Over time, I came to appreciate that moths provided a huge variety of incredibly rich tales about ecology and evolution, camouflage and conservation. The more I learned, the more I felt that moths were unduly maligned. So I set out to champion these underdogs through telling their stories in this new book, aiming to challenge people’s preconceptions, correct common misunderstandings and reboot our collective attitudes.

I really enjoyed reading about you and your daughter’s shared excitement when visiting your moth-trap. How do you think we can best encourage environmental awareness in young people on a broader scale?

First up, my daughter and I came to believe that moths provided surprisingly good ambassadors for natural beauty. This is by dint of their unexpected accessibility (there are probably hundreds of species living covertly around your garden), their unanticipated beauty (many moths ‘out-colour’ our butterflies!) and their welcome placidity (unlike most flighty insects, moths typically sit peaceably, thereby allowing prolonged perusal). To a certain extent, I think the same virtues, when converted into principles, apply to encouraging environmental awareness in youngsters, because there’s no substitute for first-hand experience. Let’s increasingly make wildlife accessible through urban nature reserves: Carlton Marshes on the outskirts of Lowestoft is a good recent example. Let’s showcase the beauty of animals and plants, running events that draw people’s attention to experiences that they would likely otherwise miss. And let’s put particular effort into helping people see non-skittish creatures: a close-up encounter with a ladybird is more likely to achieve a lasting impression than a distant view of a flying bird.

Your book is filled with extraordinary and surprising facts about moths. Do you have any particular facts or discoveries that you’d like to share with us here?

Gosh, there are so many amazing factual nuggets that it’s hard to pick just a few. For a start, I love moths’ tales of mimicry (clearwings disguise themselves as wasps), camouflage (some moths conceal themselves as desiccated leaves, twigs and even bird poo) and migratory prowess (tiny,  fragile creatures flying a thousand-plus miles). There’s wackiness too: china-mark moths, whose caterpillars live underwater; Sandhill Rustic, whose adults can swim underwater; Scarce Silver-lines, which sings from oak trees; various moths that are engaged in an evolutionary arms race with bats; Indian Meal Moth and Wax Moth, whose caterpillars can digest polyethylene and polypropylene (perhaps conceivably hinting at a solution to the global plastics problem?); and even one New World moth whose cells have proved critical for producing the Novavax COVID vaccine.

fragile creatures flying a thousand-plus miles). There’s wackiness too: china-mark moths, whose caterpillars live underwater; Sandhill Rustic, whose adults can swim underwater; Scarce Silver-lines, which sings from oak trees; various moths that are engaged in an evolutionary arms race with bats; Indian Meal Moth and Wax Moth, whose caterpillars can digest polyethylene and polypropylene (perhaps conceivably hinting at a solution to the global plastics problem?); and even one New World moth whose cells have proved critical for producing the Novavax COVID vaccine.

In terms of personal discoveries, dedicating a year to moths provided a rich vein of opportunities to try and push the boundaries of knowledge, particularly where this helped conservation organisations. Two finds particularly stand out. Helping out on a Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust survey, we came across the first adult female Marsh Moth seen in Britain since 1948; in the intervening seventy years, only males of this quixotic species had been seen! Then, within a mile of my Norwich home, I contrived to track down a new site for one of our most threatened and poorly understood moths, Marsh Carpet. As far as I am aware, the three we caught were the only adults seen anywhere in Britain that year and more than anyone had caught in a single night for years. Even better, this set in train a relationship between Butterfly Conservation and the land manager (Environment Agency), which should help protect the moth here. Both discoveries speak volumes about both how much we have to learn about these wonderful animals and how readily even inexperienced and distinctly amateur moth-ers can make tangible contributions to conservation.

Which aspect of documenting the moths did you find the most challenging?

In a year-long quest to see rare and remarkable moths across the whole of Britain, failure constantly whispers its name. It only takes one thing to go wrong, from bad weather, early flight season or late emergence to inept choice of survey sites and elusive species, for the entire pursuit to fail. With relatively inflexible dates to boot, we really were reliant on everything going right on every trip, which is a high-risk strategy when, for example, driving eleven hours to Scotland’s Ardnamurchan Peninsula to look for a particular sun-loving, day-flying moth. I guess the other thing to emphasise is that whereas moth-trapping in your garden makes for gloriously lazy wildlife-watching, simply flick the switch and let the insects come to you, surveying moths in remote places is contrastingly hard work. After a long drive, often on the back of little sleep, you need to lug heavy generators and a fleet of moth traps up steep slopes or across difficult terrain. And then you need to stay alert all night to make sure you don’t miss anything. I didn’t get much sleep that year…

sun-loving, day-flying moth. I guess the other thing to emphasise is that whereas moth-trapping in your garden makes for gloriously lazy wildlife-watching, simply flick the switch and let the insects come to you, surveying moths in remote places is contrastingly hard work. After a long drive, often on the back of little sleep, you need to lug heavy generators and a fleet of moth traps up steep slopes or across difficult terrain. And then you need to stay alert all night to make sure you don’t miss anything. I didn’t get much sleep that year…

You mention in your book that climate change is fluctuating in its effect on moths, with some species thriving in the warmer temperatures, while others are under much more pressure. Having finished your book, do you feel hopeful for the future of lepidoptera?

Yes and no. Britain’s moth ‘balance sheet’ is pretty complicated, as a recent report by Butterfly Conservation shows. Since 1900, we’ve gained nearly 140 new colonists, but perhaps fifty species have gone extinct. Others seem likely to follow: roughly one in eight of our larger moths are nationally threatened or near threatened. Four times as many species are enduring long-term declines as long-term increases and that includes previously very common and widespread ‘generalist’ moths such as Garden Tiger and Garden Dart. Most worryingly of all, one-third fewer moths are flying today than fifty years ago.

On balance, that’s a gloomy picture. But there’s hope too. Among several environmental organisations, Butterfly Conservation is doing ever more to save moths, from an initiative to connect populations of Barberry Carpet to  intrepid endeavours to safeguard the UK’s only site for New Forest Burnet. This is underpinned by surging engagement with moths among folk interested in nature. During the first COVID lockdown, retailers sold out of moth traps such was the demand for the kit. In 2020, nearly 75% more people submitted records of moths to Devon’s county recorder than the previous year. There’s definitely a growing wave on enthusiasm and passion for moths, and that’s got to be a very good thing.

intrepid endeavours to safeguard the UK’s only site for New Forest Burnet. This is underpinned by surging engagement with moths among folk interested in nature. During the first COVID lockdown, retailers sold out of moth traps such was the demand for the kit. In 2020, nearly 75% more people submitted records of moths to Devon’s county recorder than the previous year. There’s definitely a growing wave on enthusiasm and passion for moths, and that’s got to be a very good thing.

Do you have any other projects in the pipeline?

Much Ado About Mothing is a book about people as well as place and moths. One of the things I learned during my travels is that many people are deterred from entering the world of moths by the difficulty of identifying them, ‘all the moths look the same’ was a regular refrain. Some brilliant field guides to moths exist, but there seemed to be a demand to complement them with a book that helped newcomers to the hobby easily put a name to our commoner species. The result is my next book, Britain’s Moths: A Gateway Guide, which came out in September 2021. It aims to be a ‘gateway’ to both the enchanting world of moths and to those more detailed field guides. I hope it inspires more and more people to discover these amazing animals – and then fall for them, just as I have done.

Much Ado About Mothing

Much Ado About Mothing

By: James Lowen

Paperback

In the latest issue of

In the latest issue of  CLM is published four times a year in March, June, September and December, and is available by

CLM is published four times a year in March, June, September and December, and is available by

I first visited as a schoolboy in 1962, just a couple of years into Skomer’s incarnation as a nature reserve, and it was a day that changed my life forever. The most overwhelming idea that stayed with me from that day was that eventually, whatever it took, I would become warden of Skomer. I finally fulfilled that long-held childhood dream in the spring of 1976. Following 10 wonderful years on Skomer I moved to North Wales where initially I was responsible for the management of 5 spectacular National Nature Reserves and in 1991, I became responsible for supervising the management of the entire series of NNRs in Wales, a position I held for over twenty years. In 2018 I became the chair of the Pembrokeshire islands conservation advisory committee and so my commitment to Skomer continues.

I first visited as a schoolboy in 1962, just a couple of years into Skomer’s incarnation as a nature reserve, and it was a day that changed my life forever. The most overwhelming idea that stayed with me from that day was that eventually, whatever it took, I would become warden of Skomer. I finally fulfilled that long-held childhood dream in the spring of 1976. Following 10 wonderful years on Skomer I moved to North Wales where initially I was responsible for the management of 5 spectacular National Nature Reserves and in 1991, I became responsible for supervising the management of the entire series of NNRs in Wales, a position I held for over twenty years. In 2018 I became the chair of the Pembrokeshire islands conservation advisory committee and so my commitment to Skomer continues.

With the recent return of the white-tailed sea eagle to Britain and the mooted return of the Lynx, living with predators is becoming a much more frequent topic of conversation. In

With the recent return of the white-tailed sea eagle to Britain and the mooted return of the Lynx, living with predators is becoming a much more frequent topic of conversation. In  beautiful pictures were covering over a fractured, damaged world. Wild creatures are struggling to make their lives work in our increasingly human-dominated landscapes, and this rich, vibrant planet is thinning out. Over the years the press releases I read, particularly from Ireland, highlighting the decline of curlews were eye-watering. It ate away at me, this relentless destruction, and I decided I had to get more involved. Not so much in the fieldwork and practicality, but in doing what I had been trained to do – tell the stories of the earth and help make the problems accessible and understandable to people like me, non-specialists who care.

beautiful pictures were covering over a fractured, damaged world. Wild creatures are struggling to make their lives work in our increasingly human-dominated landscapes, and this rich, vibrant planet is thinning out. Over the years the press releases I read, particularly from Ireland, highlighting the decline of curlews were eye-watering. It ate away at me, this relentless destruction, and I decided I had to get more involved. Not so much in the fieldwork and practicality, but in doing what I had been trained to do – tell the stories of the earth and help make the problems accessible and understandable to people like me, non-specialists who care.

Formed in 2010, the core aim of the

Formed in 2010, the core aim of the  Sadly there are many threats to badgers and, despite gaining legal protection in 1992, badger persecution is on the increase. In England, one of the biggest threats badgers face is the government licenced badger cull. Since the cull began in England in 2013, a total of 140,991 badgers have been killed, 30,345 of which have been in Devon.

Sadly there are many threats to badgers and, despite gaining legal protection in 1992, badger persecution is on the increase. In England, one of the biggest threats badgers face is the government licenced badger cull. Since the cull began in England in 2013, a total of 140,991 badgers have been killed, 30,345 of which have been in Devon. In 2019, through some very generous grants and donations, the DBG was able to fund two members to train to become licenced lay vaccinators. I was lucky enough to be one of them. Since then, we have worked in collaboration with the Somerset Badger Group to vaccinate badgers in Devon and Somerset, which has allowed us to gain valuable experience. We hope this will continue and expand in the future.

In 2019, through some very generous grants and donations, the DBG was able to fund two members to train to become licenced lay vaccinators. I was lucky enough to be one of them. Since then, we have worked in collaboration with the Somerset Badger Group to vaccinate badgers in Devon and Somerset, which has allowed us to gain valuable experience. We hope this will continue and expand in the future.

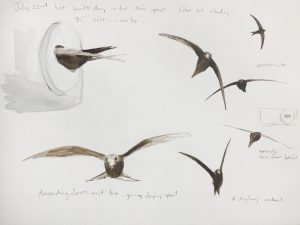

A summer visitor, the common swift appears suddenly with the change in season, swooping overhead with its unmistakeable call. From their travels to Africa, to their short breeding season in the UK, swifts appear to defy gravity with their extraordinary migratory feats, with some in flight for ten months of the year. In

A summer visitor, the common swift appears suddenly with the change in season, swooping overhead with its unmistakeable call. From their travels to Africa, to their short breeding season in the UK, swifts appear to defy gravity with their extraordinary migratory feats, with some in flight for ten months of the year. In