Across the world, there have been significant declines in butterfly and moth populations. Since 1976, 76% of UK butterfly species have seen a decrease in abundance or distribution, with the abundance of larger moths declining by 33% since 1968. This trend is echoed across UK biodiversity, with 41% of all UK species declining since the 1970s. Butterflies and moths are clear indicators of the broader health of the environment; their decline is a stark warning about our natural world.

The UK has 59 butterfly species, 57 of which are resident. There are around 2,500 species of moths in the UK, split into two groups: larger macro-moths and smaller micro-moths. Almost 70 species of butterfly and moth have become extinct in the last 100 years. A variety of threats have contributed to these extinctions and the general decline of other species, including the destruction of habitats and major land-use changes, such as the intensification of agriculture. Climate change, chemical pollution and artificial light at night have also all be identified as threats to UK populations.

Butterflies and moths have an intrinsic value in their own right, but they are also an important component in many ecosystems. They provide environmental services, including pollination and pest control and are prey for many other species, such as birds, bats and other insectivores. Butterflies and moths are also important ‘model’ organisms, used for centuries to investigate different areas of biological research and are key to understanding many diverse fields, such as pest control, mimicry, genetics and population dynamics.

The Big Butterfly Count 2021

Butterfly Conservation, a UK nonprofit environmental charity, is determined to reverse this decline. Their vision is a world where butterflies and moths thrive and can be enjoyed by everyone, everywhere. To help with the assessment of the health of our environment, Butterfly Conservation runs an annual nationwide citizen science survey, the Big Butterfly Count. Launched in 2010, it is the world’s biggest survey of butterflies.

Big Butterfly Count 2021 ran between 16th July and 8th August (read our blog to see how our NHBS staff got on this year). The results of this count showed that the overall number of butterflies recorded per count is at its lowest since the event began. Over 150,000 counts were registered this year, more than ever before, but the results showed that the populations of some of our most-loved species, such as the peacock butterfly (Aglais io), are suffering. Luckily, it’s not all bad news, as some species, such as the marbled white (Melanargia galathea), appear to be bouncing back from last year’s low numbers. But the significant, long-term decline of many butterfly and moth species in Britain is alarming.

Butterfly Conservation’s new strategy

In their new 2021-2026 strategy, launched in October 2021, Butterfly Conservation outlines a bold, ambitious road map to bringing abundance back to nature. After 16 months of reviewing their position in butterfly and moth conservation, they have defined three new strategic goals:

- Reduce the number of threatened species of butterflies and moths by half,

- Improve the condition of 100 of the most important landscapes for butterflies and moths,

- Transform 100,000 wild spaces in the UK, not just for butterflies and moths, but also for people.

To help them deliver their strategic goals, Butterfly Conservation have five initiatives. The first initiative is focused on recovery, through refocusing their science program to increase the understanding of why species are declining and how to recover their populations. They will also establish a new Threatened Species program, which will target conservation action for 65 species at serious risk. Butterfly Conservation will also expand their monitoring program to follow species recovery and gather data on a country-wide level. By 2026, they hope to have increased their species recovery actions by 65%.

The second initiative aims to inspire and enable more people to enjoy the natural world by improving access to learning, particularly for younger audiences. The third initiative is focused on uniting for wildlife, and the fourth is to tackle the threats species face, such as artificial light at night. They’ll achieve these goals by collaborating with a network of supporters and increasing their investment in research by 80% to establish five habitat quality indicators to better understand the impact of conservation work or policy changes. The final initiative focuses on managing land sustainably, by creating a land management advisory hub and delivering and demonstrating best practice land management for butterflies and months across landscapes.

Butterfly Conservation believes that the next five years are key and, through their bold new steps to conserve butterflies and moths, they can help to restore biodiversity, mitigate the climate crisis and start to rebuild the relationship between us and the natural world.

Useful resources

- These Butterfly Conservation publications on The State of Britain’s Larger Moths 2021 and The State of the UK’s Butterflies 2015, as well as Butterfly Conservation’s new strategy.

- The Butterfly Red List for Great Britain, produced by Butterfly Conservation and Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC).

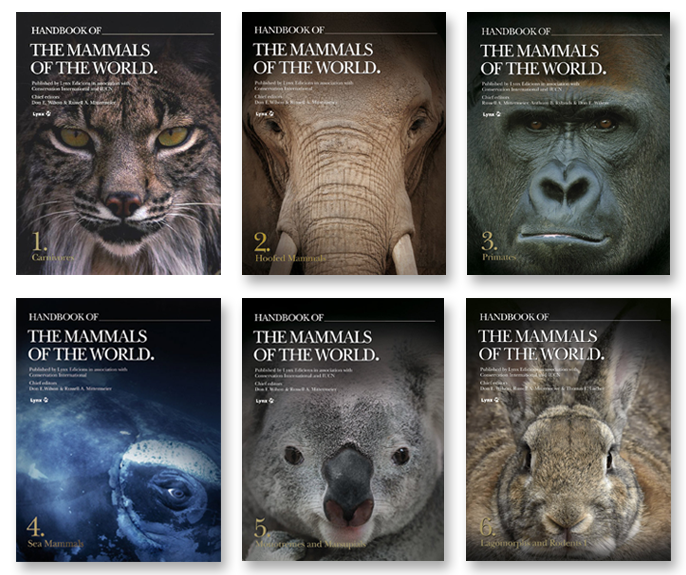

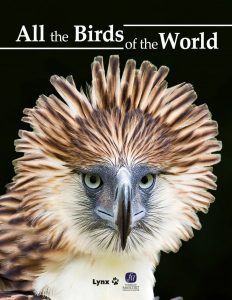

Lynx Edicions is a Barcelona-based publishing house, originally founded in 1989 to create the

Lynx Edicions is a Barcelona-based publishing house, originally founded in 1989 to create the

the line into extinction. In our Handbooks, Illustrated Checklists, Field Guides and most recently

the line into extinction. In our Handbooks, Illustrated Checklists, Field Guides and most recently

Acoustic detection is a popular and widespread method of environmental assessment, and its use is increasing, driven by the development of increasingly accessible and sophisticated detection devices.

Acoustic detection is a popular and widespread method of environmental assessment, and its use is increasing, driven by the development of increasingly accessible and sophisticated detection devices.