Welcome to our annual round-up of the books and equipment we have enjoyed reading and using this year, all chosen by members of the NHBS team. Here are our choices for 2020!

The new Browning Patriot has really impressed me this year. It is very competitively priced for a top of the range camera and produces fantastic quality photos and videos. The standout features are the 0.15s trigger speed and 0.35s recovery time between pictures ensuring you catch even the fastest moving of animals. I would highly recommend this camera for professionals and naturalists alike.

Gemma – Wildlife Equipment Specialist

Orchard: A Year in England’s Eden

Orchard: A Year in England’s Eden

Orchards have been a traditional component of the British landscape for many centuries and their value for wildlife has long been underestimated. This passionate eulogy observes over a single year the abundant wildlife in one of the few traditional orchards left in Britain. It is a brilliantly written and informative insight into the ecological niche traditional orchards can provide and the benefit they can have for the larger ecosystems around them. Unfortunately, as in so much of the UK’s agricultural landscape, modern orchards are often deserts of biodiversity: depending on expensive machinery, pesticide controls and extensive pruning to keep competitive. However the authors make an excellent case for working with nature rather than against it, to control pests and maintain productivity that is both commercially viable and provides a haven for nature. I enjoyed this book immensely and it has inspired me to plant a couple of apple trees in my tiny back garden.

Nigel – Books and Publications

Field Guide to the Caterpillars of Great Britain and Ireland

Field Guide to the Caterpillars of Great Britain and Ireland

This recent addition to the Bloomsbury Nature Guides was published in March. All throughout the first UK lockdown, I spent a considerable amount of time in the NHBS warehouse, and the book’s popularity was very visible: spotting the bright orange spine on the book trolleys and the packing benches always cheered me. This field guide is very accessible with a comprehensive introduction, a lot of detail in the species accounts, and outstanding illustrations. It’s perfect for both the novice with a little curiosity, like myself, and for experienced naturalists.

Anneli – Head of Finance and Operations

I’ve loved reading British Wildlife this year, particularly the wildlife reports and columns. There’s been some amazing articles, including a recent Patrick Barkham article ‘Crisis point for the conservation sector’.

Natt – Head of Sales and Marketing

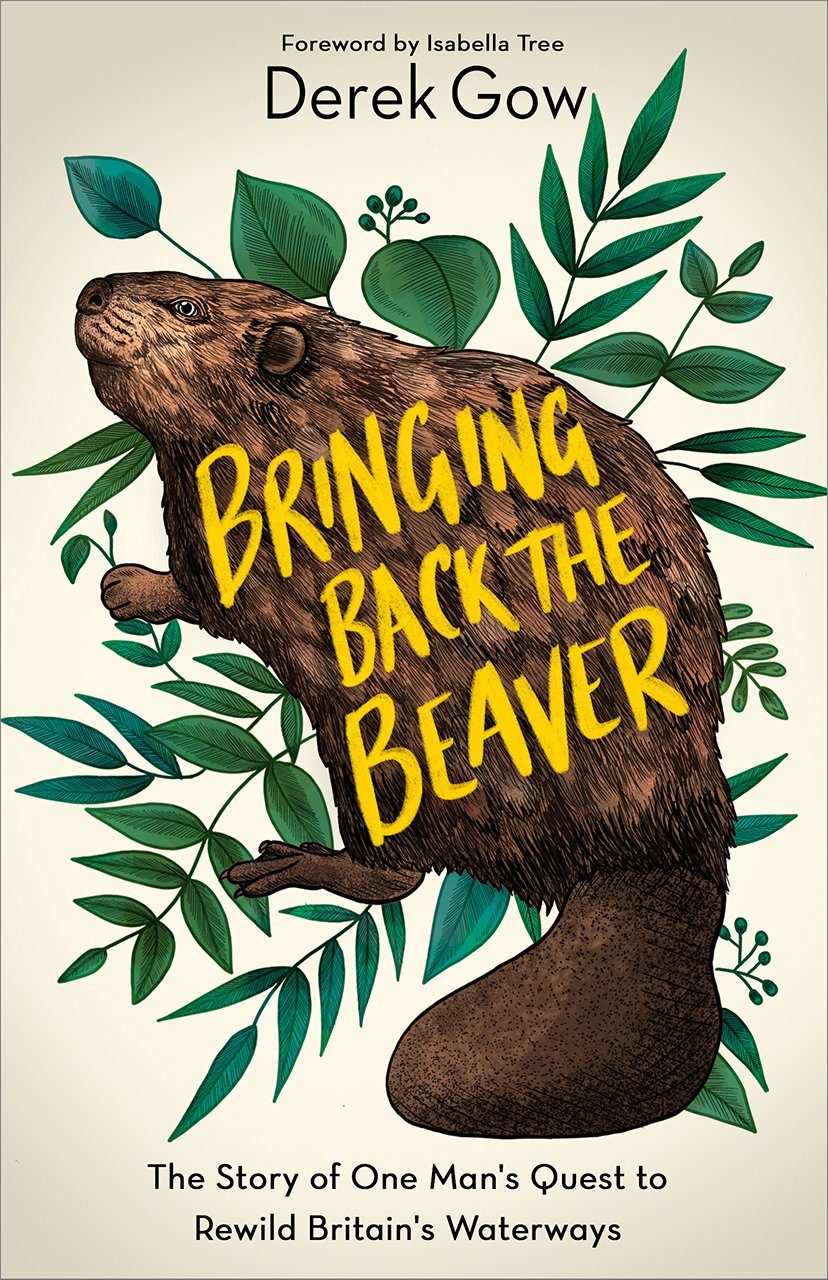

After having a previous life as a beaver researcher and seeing Derek Gow in action, Bringing Back the Beaver had to be my staff pick of 2020. Derek’s passion for beavers and nature in general really comes across and I was entertained from the first page to the last whilst being educated along the way.

Hannah – Operations Assistant

I bought this mug and notebook as gifts for my Mum who, as a trainee beekeeper, adored them! Both products are high quality, adorable and have some lovely words about the bumblebee on it. The hand-drawn bumblebee image is detailed, lifelike and adds to the charisma of the products.

In addition to this, for every sale made, a donation is given to the Bumblebee Conservation Trust! If you are a bee lover and would like to help make a difference to conserving this enchanting species, then I highly recommend these items.

Holly – Customer Services

My pick this year is the hedgehog nest box. When an underweight and sick hedgehog had to be rescued from outside our offices this year, we were advised to place a hedgehog box out for the hedgehog’s return once she had recovered. The Hedgehog Nest Box was an obvious choice, being sturdy, well-designed and tested extensively by the Hedgehog Preservation Society. The in-built tunnel ensures inhabitants are kept safe from draughts and any unwanted visitors, and the removable lid meant we could fit a nestbox camera inside the nesting chamber to keep an eye on the recently recovered hog.

Antonia – Deputy Wildlife Equipment Manager

1080p HD Wired Outdoor Bird Feeder Camera

1080p HD Wired Outdoor Bird Feeder Camera

I love being able to see the wildlife in my garden but never want to scare any of it away and this little camera is a great solution to that problem. It allows you to live stream footage in full HD straight to your TV or monitor, day and night. It is small enough to fit into a nest box and watch the “behind the scenes” of the start of garden birds’ lives, or the comings and goings of hedgehogs from their daytime refuge in a hedgehog box. But on top of that, with this camera’s completely weatherproof casing, it can be used outside of nest box season to watch feeders in the garden or small mammal highways with no additional protection.

Beth – Wildlife Equipment Specialist

Despite having only a ten minute walking commute to the office here in Totnes, the inclement winter weather means I have to be well prepared if I want to arrive dry and warm! That’s why my pick this year is the Aquapac Trailproof Daysack. Its all-welded construction and roll top seal make it a thoroughly reliable waterproof pack. I’ve used it for a variety of purposes, from wet weather running and hiking and even loading it with groceries! It’s 500d vinyl construction makes it a very rugged pack for day hikes and the padded straps mean it can hold a surprising amount of weight whilst remaining comfortable. If you’re looking for a versatile hard-wearing dry pack then this is it!

Johnny – Wildlife Equipment Specialist

Owls of the Eastern Ice is a spellbinding memoir of determination and obsession with safeguarding the future of this bird of prey that firmly hooked its talons in me and did not let go.

Leon – Catalogue Editor

Having worked as a freelance bat surveyor for a couple of years now, I can say that the BatBox Duet is by far my favourite entry/mid-level bat detector on the market. The main reason for this is that it enables me to simultaneously monitor calls via frequency division – meaning that a bat calling at any pitch will be heard in real time – and heterodyne feeds, affording me a rough idea of which species I’m listening to. It is robust and easy to use, and comes with BatScan pro, a comprehensive analysis program that allows recorded calls to be studied later. With an affordable price to boot, this detector is always an easy recommendation for those looking to advance their bat knowledge.

Josh – Wildlife Equipment Specialist

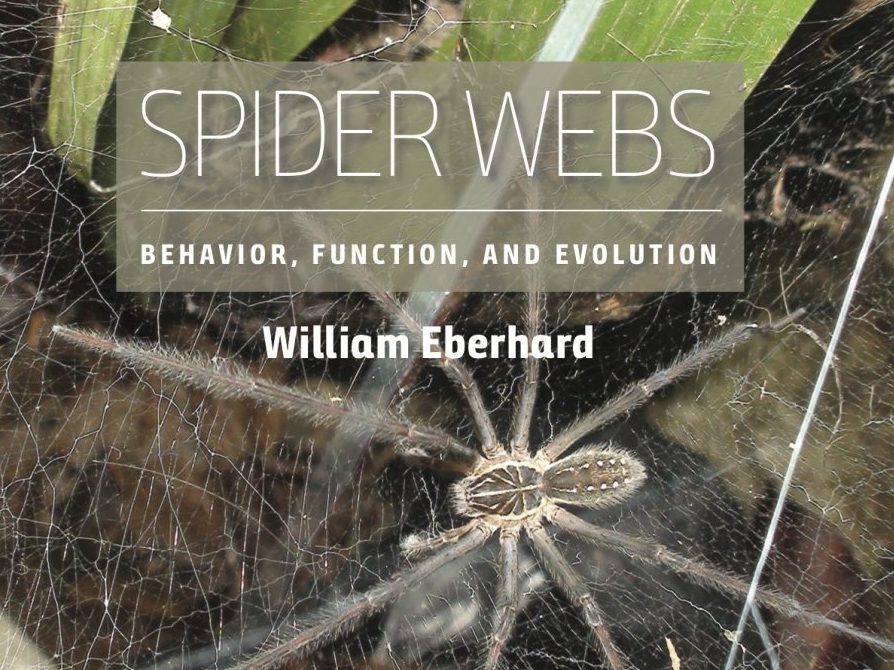

You point out that the majority of published behavioural observations have been of mature females. What do we know about males and immature spiders? Is web construction specifically a female activity? Or have we just not looked hard enough?

You point out that the majority of published behavioural observations have been of mature females. What do we know about males and immature spiders? Is web construction specifically a female activity? Or have we just not looked hard enough? You mention that orb webs are neither the pinnacle of web evolution nor necessarily the optimally designed structures that they are often claimed to be. Most organismal traits are a product of history and contingency as much as natural and sexual selection. I might be asking you to speculate here, but, in your opinion, are there any particular evolutionary thresholds that spiders have not been able to cross that would make a big difference for web construction?

You mention that orb webs are neither the pinnacle of web evolution nor necessarily the optimally designed structures that they are often claimed to be. Most organismal traits are a product of history and contingency as much as natural and sexual selection. I might be asking you to speculate here, but, in your opinion, are there any particular evolutionary thresholds that spiders have not been able to cross that would make a big difference for web construction? Producing a book of this scope must have been a tremendous job, and you remark that a thorough, book-length review of spider webs had yet to be written, despite more than a century of research on spiders. With the benefit of hindsight, would you embark on such an undertaking again?

Producing a book of this scope must have been a tremendous job, and you remark that a thorough, book-length review of spider webs had yet to be written, despite more than a century of research on spiders. With the benefit of hindsight, would you embark on such an undertaking again?

Has data from the Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) you have developed been used in your books?

Has data from the Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) you have developed been used in your books? Why did you choose Kestrels as the subject for your latest book?

Why did you choose Kestrels as the subject for your latest book? Did you encounter any challenges collecting data for your new book: Kestrel?

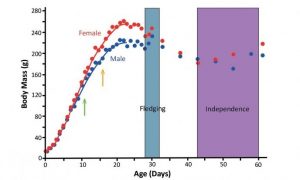

Did you encounter any challenges collecting data for your new book: Kestrel? For four successive years we set up an array of video cameras filming breeding Kestrels in a barn in Hampshire. We had one camera filming the comings and goings of the adults and, later the fledglings, and two cameras in the nest box watching egg laying, incubation, hatching and chick growth. We filmed 24 hours every day, turning on IR lights to film at night. We measured egg laying intervals to the nearest minute, found accurate hatch times and watched every prey delivery. We also set up live traps where we knew the male hunted so we could weigh the local voles and mice and estimate how many kgs of rodent it takes to make 1kg of Kestrel. The filming was interesting – over the years the adults brought in slow worms, lizards, frogs and moths, as well as voles, mice and shrews. One male also brought in a weasel. This has long been suspected, but never-before filmed.

For four successive years we set up an array of video cameras filming breeding Kestrels in a barn in Hampshire. We had one camera filming the comings and goings of the adults and, later the fledglings, and two cameras in the nest box watching egg laying, incubation, hatching and chick growth. We filmed 24 hours every day, turning on IR lights to film at night. We measured egg laying intervals to the nearest minute, found accurate hatch times and watched every prey delivery. We also set up live traps where we knew the male hunted so we could weigh the local voles and mice and estimate how many kgs of rodent it takes to make 1kg of Kestrel. The filming was interesting – over the years the adults brought in slow worms, lizards, frogs and moths, as well as voles, mice and shrews. One male also brought in a weasel. This has long been suspected, but never-before filmed.

After two decades of researching them, has your own attitude towards them changed?

After two decades of researching them, has your own attitude towards them changed? You mention many people seem to think adult flies lack brains, this misconception being fuelled by watching them fly into windows again and again. This may seem like a very mundane question but why, indeed, do they do this?

You mention many people seem to think adult flies lack brains, this misconception being fuelled by watching them fly into windows again and again. This may seem like a very mundane question but why, indeed, do they do this? You explain how insect taxonomists use morphological details such as the position and numbers of hairs on their body to define species. I have not been involved in this sort of work myself, but I have always wondered, how stable are such characters? And on how many samples do you base your decisions before you decide they are robust and useful traits? Is there a risk of over-inflating species count because of variation in traits?

You explain how insect taxonomists use morphological details such as the position and numbers of hairs on their body to define species. I have not been involved in this sort of work myself, but I have always wondered, how stable are such characters? And on how many samples do you base your decisions before you decide they are robust and useful traits? Is there a risk of over-inflating species count because of variation in traits?