Renowned for its incredible and diverse wildlife, it is no wonder that Skomer Island receives thousands of visitors year upon year. Famous for its thriving populations of seabirds, grey seals and its vast swathes of spring flowers, Skomer is a fantastic example of how carefully managed eco-tourism works alongside conservation.

Renowned for its incredible and diverse wildlife, it is no wonder that Skomer Island receives thousands of visitors year upon year. Famous for its thriving populations of seabirds, grey seals and its vast swathes of spring flowers, Skomer is a fantastic example of how carefully managed eco-tourism works alongside conservation.

Mike Alexander was Warden of Skomer for ten years, and has had links to the island for over six decades. He is now Chair of the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales and the Pembrokeshire Islands Conservation Advisory Committee. Illustrated with his own stunning photographs of the flora and fauna, this book is a comprehensive history of the island and its inhabitants.

Could you tell us a bit about your background and where the motivation for your book came from?

I first visited as a schoolboy in 1962, just a couple of years into Skomer’s incarnation as a nature reserve, and it was a day that changed my life forever. The most overwhelming idea that stayed with me from that day was that eventually, whatever it took, I would become warden of Skomer. I finally fulfilled that long-held childhood dream in the spring of 1976. Following 10 wonderful years on Skomer I moved to North Wales where initially I was responsible for the management of 5 spectacular National Nature Reserves and in 1991, I became responsible for supervising the management of the entire series of NNRs in Wales, a position I held for over twenty years. In 2018 I became the chair of the Pembrokeshire islands conservation advisory committee and so my commitment to Skomer continues.

I first visited as a schoolboy in 1962, just a couple of years into Skomer’s incarnation as a nature reserve, and it was a day that changed my life forever. The most overwhelming idea that stayed with me from that day was that eventually, whatever it took, I would become warden of Skomer. I finally fulfilled that long-held childhood dream in the spring of 1976. Following 10 wonderful years on Skomer I moved to North Wales where initially I was responsible for the management of 5 spectacular National Nature Reserves and in 1991, I became responsible for supervising the management of the entire series of NNRs in Wales, a position I held for over twenty years. In 2018 I became the chair of the Pembrokeshire islands conservation advisory committee and so my commitment to Skomer continues.

I had long dreamed of writing a book about Skomer, but in truth had little idea of how I might achieve that goal. Skomer is a cultural landscape shaped over thousands of years by people striving to make a living. I wanted to show how the island has evolved in response to changing human values, attitudes and interventions. I also wanted an opportunity to demonstrate what nature conservation means in practice. Reserves like Skomer are the most powerful advocate for nature that we could possibly have. The island gives visitors an almost magical insight into somewhere that transcends our ordinary world, where one close encounter with a puffin may speak more eloquently for conservation than a thousand words ever could.

Previous to the island becoming an NNR in 1959, you mention Skomer’s agricultural history. Could you tell us here a little about the island’s past?

Skomer’s time as a nature reserve spans barely a moment in its history. People have occupied Skomer for millennia, and archaeologist John Evans has described Skomer as possibly unique in the completeness of its archaeological remains. Present day visitors to the island can clearly pick out faint patterns of the distant past: field systems, lynchets, hut circles and more. Until recently, archaeologists and historians believed that apart from rabbit trapping and livestock grazing, the island had been abandoned after the Iron Age. However, new excavations in 2017 revealed the presence of medieval land clearance and ploughing.

During my ten years living on Skomer I became increasingly interested in the people who had lived there before me and most of all, the 19th century inhabitants who had farmed and made their living on the island. The people of the 19th century left the heaviest footprints as theirs was a time when people imposed their will on the island, shaping the land to meet their needs. This was a period of intense intervention and although it began to fade towards the end of the century, it was a time when people had the most impact on the island, its scenery and vegetation. How long will it be before the Victorian farmers’ footprints fade away? We, the later islanders, have become noninterventionists, and observers of nature’s progress. Ours should be the lightest of all footprints, and so perhaps the impact of the 19th century will, for now, be the most enduring of all human influences.

Recent news of Skomer’s thriving populations of seabirds like the puffin and Manx shearwater offer much hope. What major changes do you think are necessary to ensure species recovery and habitat restoration in Britain?

My generation has grown up with an almost subliminal pessimism about the fate of our wildlife to the point where decline seems inevitable and we can only hope to slow the rate of it. To have seen Skomer thrive throughout its time as a nature reserve is contrary to nearly everything I have grown up to believe, and yet it is important to remember that Skomer once had the potential for so much more. We know from photographs taken around the turn of the last century, that there was a minimum island population of around 100,000 Guillemots: four times the present number. The photographs also show the grassy slopes above the cliffs thick with Puffins, where now they only form a thin fringe. Perhaps these things will not be possible again, but it is a vital reminder never to set our sights too low and to hold on to that vision of what the future could be.

Species and habitat recovery will only happen when our policies and legislation are translated into action. Good intentions alone will achieve nothing. It is quite ironic that despite the enormous growth in public concern and protest about the fate of our natural environment, governments are failing to provide the essential resources.

The NNRs, along with all other protected areas, will be a central and essential component of any species and habitat recovery or restoration programme. They are the stepping stones, the vital reservoirs and the crucial resources that will enable landscape scale recovery in Britain.

With restricted movement during the Covid-19 pandemic that many are referring to as the ‘anthropause’, people across the globe have noticed changes to their local wildlife. How has the lack of eco-tourism affected the wildlife on Skomer during this time?

Skomer is an extremely fragile island with hundreds of thousands of seabirds. Puffins and Manx Shearwaters nest in shallow burrows, while the cliffs provide homes for thousands of Guillemots, Razorbills and Kittiwakes. As a consequence, all visitors to the island understand that they must keep to the system of marked footpaths at all times. This has made it possible for us to claim with confidence that visitors to Skomer have no impact on the wildlife that they come to enjoy. So apart from overgrown paths, there has been no significant discernible impact.

There are plenty of signs from elsewhere that wildlife has responded positively to the lack of human disturbance. It may well be that some species will gain a short-term advantage, but I am not convinced that the impact of Covid-19 on wildlife will be anything more than a very minor, and almost irrelevant, hiccup, unless of course we can learn from the experience. We must learn to change our behaviour and realise that we will not survive on this planet if we regard unfettered consumerism as our main purpose in life.

Do you have any other projects on the horizon you’d like to tell us about?

I will take a break from writing and concentrate on photography. I was recently elected Chair of the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales and I am looking forward to devoting much of my time to working for the Trust.

Skomer Island

By: Mike Alexander

Hardback | Due April 2021 | £29.99

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

With the recent return of the white-tailed sea eagle to Britain and the mooted return of the Lynx, living with predators is becoming a much more frequent topic of conversation. In

With the recent return of the white-tailed sea eagle to Britain and the mooted return of the Lynx, living with predators is becoming a much more frequent topic of conversation. In  beautiful pictures were covering over a fractured, damaged world. Wild creatures are struggling to make their lives work in our increasingly human-dominated landscapes, and this rich, vibrant planet is thinning out. Over the years the press releases I read, particularly from Ireland, highlighting the decline of curlews were eye-watering. It ate away at me, this relentless destruction, and I decided I had to get more involved. Not so much in the fieldwork and practicality, but in doing what I had been trained to do – tell the stories of the earth and help make the problems accessible and understandable to people like me, non-specialists who care.

beautiful pictures were covering over a fractured, damaged world. Wild creatures are struggling to make their lives work in our increasingly human-dominated landscapes, and this rich, vibrant planet is thinning out. Over the years the press releases I read, particularly from Ireland, highlighting the decline of curlews were eye-watering. It ate away at me, this relentless destruction, and I decided I had to get more involved. Not so much in the fieldwork and practicality, but in doing what I had been trained to do – tell the stories of the earth and help make the problems accessible and understandable to people like me, non-specialists who care.

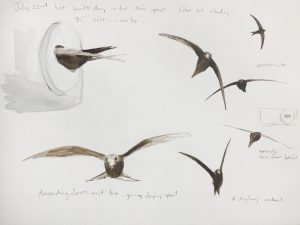

A summer visitor, the common swift appears suddenly with the change in season, swooping overhead with its unmistakeable call. From their travels to Africa, to their short breeding season in the UK, swifts appear to defy gravity with their extraordinary migratory feats, with some in flight for ten months of the year. In

A summer visitor, the common swift appears suddenly with the change in season, swooping overhead with its unmistakeable call. From their travels to Africa, to their short breeding season in the UK, swifts appear to defy gravity with their extraordinary migratory feats, with some in flight for ten months of the year. In

From the Sunday Times bestselling author of

From the Sunday Times bestselling author of

Heathlands defy ready definition. The diverse places that we call heaths are cultural landscapes which are overlain with the language of ecology. It is unnecessary to reconcile these different perspectives as both traditions offer a path to understanding what makes our heathlands special.

Heathlands defy ready definition. The diverse places that we call heaths are cultural landscapes which are overlain with the language of ecology. It is unnecessary to reconcile these different perspectives as both traditions offer a path to understanding what makes our heathlands special. It is not inevitable that the catastrophic losses of the recent past are the destiny of our remaining heaths. Whilst there are still significant challenges to overcome, we know enough about these habitats to secure their place in the countryside of the future, as an integral part of British culture and home to a wealth of species that occupy ecosystems of immense richness.

It is not inevitable that the catastrophic losses of the recent past are the destiny of our remaining heaths. Whilst there are still significant challenges to overcome, we know enough about these habitats to secure their place in the countryside of the future, as an integral part of British culture and home to a wealth of species that occupy ecosystems of immense richness. Heathlands are a great deal more than just carpets of heathers. A heathland landscape can embrace habitats as diverse as rocks and lakes and bogs, even temporary stands of arable and wartime concrete. The component habitats of a large functioning heathland are naturally dynamic, with species dependant on all sorts of habitat formations, from bare ground to the decaying of cowpats. The great antiquity of heathland ecosystems is reflected in the network of interdependent species, many of which are associated with large herbivores, fire and occasional gross disturbance of the soil. Whilst charismatic birds and reptiles have traditionally claimed the limelight, the biological wealth of the heath is better expressed through its invertebrates, lichen and wildflowers.

Heathlands are a great deal more than just carpets of heathers. A heathland landscape can embrace habitats as diverse as rocks and lakes and bogs, even temporary stands of arable and wartime concrete. The component habitats of a large functioning heathland are naturally dynamic, with species dependant on all sorts of habitat formations, from bare ground to the decaying of cowpats. The great antiquity of heathland ecosystems is reflected in the network of interdependent species, many of which are associated with large herbivores, fire and occasional gross disturbance of the soil. Whilst charismatic birds and reptiles have traditionally claimed the limelight, the biological wealth of the heath is better expressed through its invertebrates, lichen and wildflowers.

Professor Jeff Ollerton is a researcher, educator, consultant and author, specialising in mutualistic ecological relationships – in particular, those between plants and their pollinators. Now one of the world’s leading experts on pollinators and pollination, he has conducted field research in the UK, Australia, Africa, and Tenerife, and published a huge body of ground-breaking research which is highly-cited and used at both national and international levels to inform conservation efforts. Jeff currently holds Visiting Professor positions at the University of Northampton in the UK and Kunming Institute of Botany in China.

Professor Jeff Ollerton is a researcher, educator, consultant and author, specialising in mutualistic ecological relationships – in particular, those between plants and their pollinators. Now one of the world’s leading experts on pollinators and pollination, he has conducted field research in the UK, Australia, Africa, and Tenerife, and published a huge body of ground-breaking research which is highly-cited and used at both national and international levels to inform conservation efforts. Jeff currently holds Visiting Professor positions at the University of Northampton in the UK and Kunming Institute of Botany in China.

While professional scientific research, alongside informed policy change, will obviously be key in directing the future of pollinators around the world, you also mention the importance of amateur naturalists and citizen scientists in collecting data and providing some of the legwork behind sustained long-term studies. What advice would you give to a non-professional individual who wishes to get involved with pollinator conservation? (eg. volunteering, donating to charities/organisations, lobbying for policy change etc.)

While professional scientific research, alongside informed policy change, will obviously be key in directing the future of pollinators around the world, you also mention the importance of amateur naturalists and citizen scientists in collecting data and providing some of the legwork behind sustained long-term studies. What advice would you give to a non-professional individual who wishes to get involved with pollinator conservation? (eg. volunteering, donating to charities/organisations, lobbying for policy change etc.) I discovered lots of interesting things from your book that I previously didn’t know – such as the fact that there are pollinating lizards! In all of your years of study, what is the most fascinating fact that you have learned about pollinators?

I discovered lots of interesting things from your book that I previously didn’t know – such as the fact that there are pollinating lizards! In all of your years of study, what is the most fascinating fact that you have learned about pollinators? Finally, what are you working on currently, and do you have plans for further books?

Finally, what are you working on currently, and do you have plans for further books?