Thermal scopes detect and display temperature variations and can use the infrared energy (heat) emitted by warm-blooded animals to create a distinct thermal profile. They produce an image that displays different temperatures in different colours which can be used to visibly detect the location of animals that may not otherwise be seen due to lack of light.

Thermal scopes are typically used to survey nocturnal or elusive species. Particularly useful when used in bat surveys, they can be used to identify roost access points with greater accuracy and can provide improved-quality images of animals in flight. Thermal scopes are also used in surveys for other wildlife, including bird ringing programmes and nest box monitoring, particularly for Pine Martens. This non-invasive technology allows ecologists to monitor wildlife whilst minimising disturbance, allowing for more accurate data reporting on wildlife behaviour. They can be used during both the day and night and offer different colour palettes to improve visibility in different environmental conditions.

Thermal scopes are designed with varied capabilities and are suitable for a range of users, from naturalists to ecologists. Here we explore a range of thermal scopes available on our website, including both affordable and more advanced options, and highlight the benefits and features of each.

Pulsar Telos XP50 Thermal Imaging Monocular

Featuring an industry-leading thermal sensor, this high performance monocular provides high resolution imagery in all conditions and has a built-in laser range finder (LRF) capable of long-distance measurements. Durable and user–friendly, these waterproof optics are suitable for all weather conditions and are designed with a wear-resistant rubberised body to maximise longevity.

Featuring an industry-leading thermal sensor, this high performance monocular provides high resolution imagery in all conditions and has a built-in laser range finder (LRF) capable of long-distance measurements. Durable and user–friendly, these waterproof optics are suitable for all weather conditions and are designed with a wear-resistant rubberised body to maximise longevity.

- Sensor: 640 × 480, 17µm, <18mK NETD

- Lens: 50mm/F1.0 Germanium lens

- Magnification: 2.5-10.0× (and 4× digital zoom)

- Frame rate: 50Hz

- Detection range: 1,800m

- Video/photo resolution: 1024 × 768

- Rating: IPX7

- Operating time: Up to 8.5hrs

- Weight: 720g with battery

Pixfra Sirius S650 Thermal Imaging Monocular

A compact, powerful monocular offering an incredible optical performance. This monocular has an impressive magnification and detection range, making it ideal for wildlife observation and recording thermal images at a distance. And with 64GB built-in storage, still images or video can be recorded at the push of a button.

- Sensor: 640 × 512, 12µm, <18mK NETD

- Lens: 50mm/F0.9

- Magnification: 3.45 ×

- Frame rate: 50Hz

- Detection range: Up to 2,600m

- Rating: IP67

- Operating time: Up to 6 hours

- Weight: 537g

Pixfra Arc 600 Series Thermal Imaging Monoculars

A great all-round choice at a competitive price point, this thermal monocular is compact, lightweight and has the widest field of view in the Pixfra range making it ideal for emergence surveys. A highly robust chassis and an IP67 rating mean that this monocular is incredibly durable and is built to withstand poor weather conditions, drops and scrapes in the field.

- Sensor: 640 × 512, 12µm, NETD <30mK

- Lens: 13mm/F1.0

- Magnification: 0.875×

- Frame rate: 50Hz

- Detection range: 670m

- Rating: IP67

- Operating time: Up to 6.5h

- Weight: 304g (excluding battery)

Pulsar Merger LRF XP50 Thermal Imaging Binoculars

High-spec, professional-level thermal binoculars, this device features a built-in laser range finder and a highly sensitive thermal sensor operating across a long detection range. Lightweight and durable, these advanced thermal optics are highly resistant to harsh environmental conditions and can be submerged in up to one meter of water for up to 30 minutes.

- Sensor: 640 × 480, 17 µm, NETD <25mK

- Lens: Fast aperture F50/1.0 germanium lens

- Magnification: 2.5×-20× (and digital 8× zoom)

- Frame rate: 50Hz

- Detection range: 1,800m

- Video/photo resolution: 1024p × 768p

- Rating: IPX7

- Operating time: Approx 10hrs

- Weight: 800g

Pulsar Axion 2 XQ35 Pro Thermal Imaging Monocular

A lightweight and highly portable mid-range monocular, this thermal scope features an industry-leading sensor and a high-quality aperture objective lens to ensure clear, distinguished viewing. Innovative in design, this monocular allows for still image and video recording to internal memory, and is Wi-Fi enabled to allow for easy downloads to a mobile device.

- Sensor: 384 × 288, 17 µm, NETD <25mK

- Lens: Fast aperture Germanium 35mm/F1.0 objective lens

- Magnification: 2-8×,

- Detection range:1,300m @ 1.8m

- Video/photo resolution: 528 x 400p

- Rating: IPX7

- Operating time: Up to 11 hours

- Weight: 380g

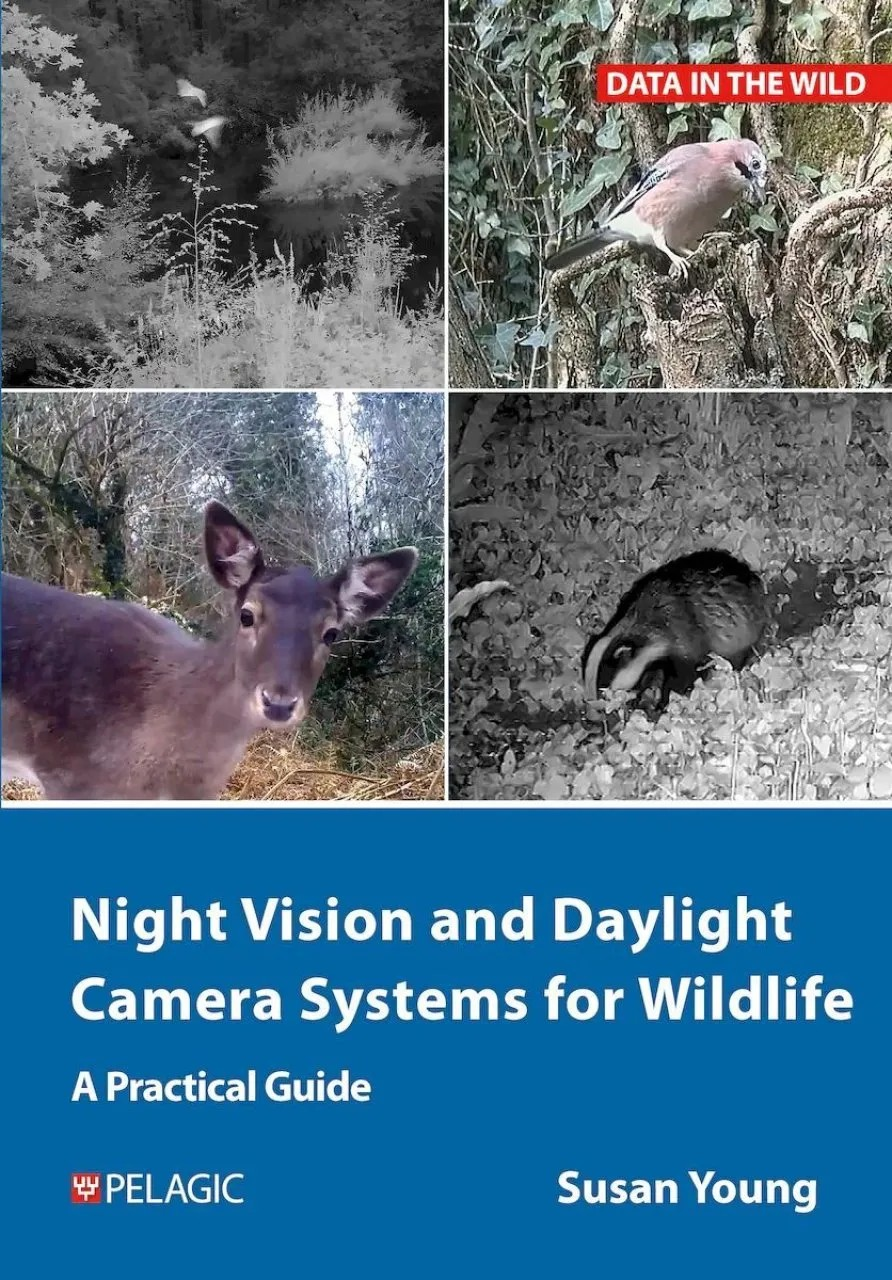

Recommended Reading:

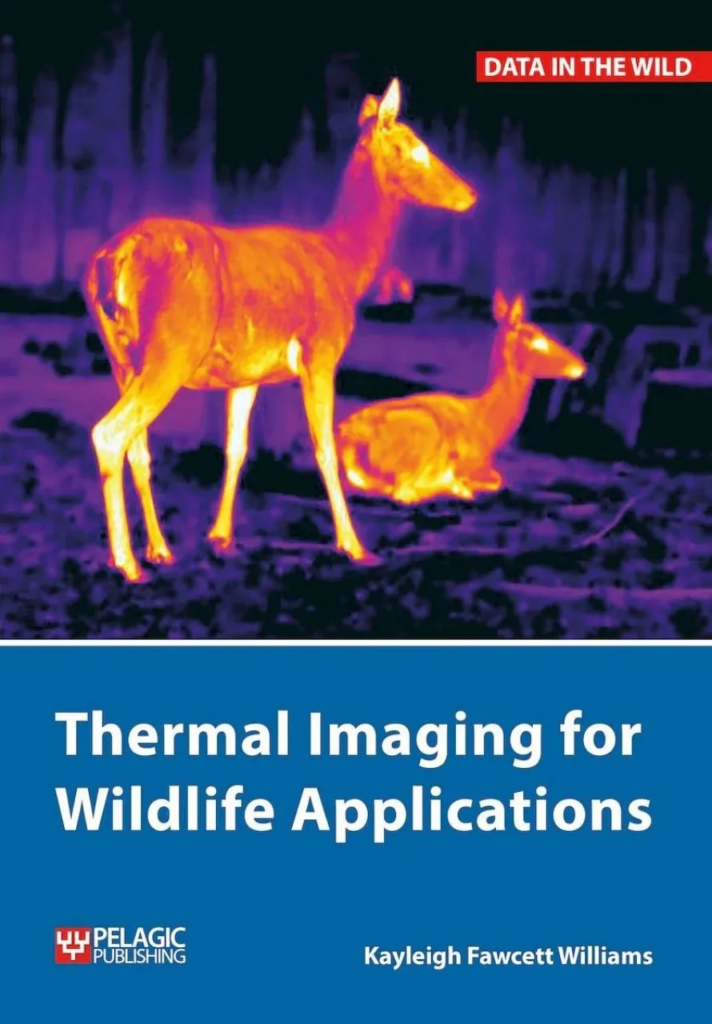

Thermal Imaging for Wildlife Applications

Thermal Imaging for Wildlife Applications

Paperback & Hardback | Oct 2023

A practical guide that collects findings from academic research and applied field protocols to inform readers on the fundamentals of the technology, its methods, equipment and applications.

Susan Young is a photographer and writer based in South Devon, who has a wealth of experience in wildlife photography. She has authored several books, including

Susan Young is a photographer and writer based in South Devon, who has a wealth of experience in wildlife photography. She has authored several books, including