From the author of The Seabird’s Cry, Adam Nicolson’s new book The Sea Is Not Made of Water offers a glimpse into the intricacies and minutiae of the intertidal zone. Blending ecology and human history, poetry and prose, Adam takes us on a fascinating journey to the shore.

From the author of The Seabird’s Cry, Adam Nicolson’s new book The Sea Is Not Made of Water offers a glimpse into the intricacies and minutiae of the intertidal zone. Blending ecology and human history, poetry and prose, Adam takes us on a fascinating journey to the shore.

Adam is a journalist and prize-winning author of books on history, landscape and nature – among many other accolades, he won the 2018 Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing. He has also made several television and radio series on a variety of subjects.

First of all, we loved The Seabird’s Cry and were very excited to learn of The Sea Is Not Made of Water about intertidal zones. Could you tell us about what drew you to this habitat and the inspiration behind your book?

For nearly thirty years now I have been going to stay in a small house at the head of a bay on the west coast of Scotland. It is somewhere my wife’s family have been going for generations and now our children and grandchildren love it too. It has everything you might long for from a place like that: cliffs, woods, waterfalls, a dark beach made of basalt sands, a lighthouse, a ruined castle, stories, beauty, birds, fish; but one thing it did not have because of the geology, was a rockpool. For years I have dreamed of making one – a place of stillness set in the tide, and this book is the story of how I made three of them in different parts of the bay; one dug in with a pickaxe; one made by damming a narrow exit to the sea from a hollow so that the dam held the pool behind it; and one by making a circular wall low down in the intertidal.

For nearly thirty years now I have been going to stay in a small house at the head of a bay on the west coast of Scotland. It is somewhere my wife’s family have been going for generations and now our children and grandchildren love it too. It has everything you might long for from a place like that: cliffs, woods, waterfalls, a dark beach made of basalt sands, a lighthouse, a ruined castle, stories, beauty, birds, fish; but one thing it did not have because of the geology, was a rockpool. For years I have dreamed of making one – a place of stillness set in the tide, and this book is the story of how I made three of them in different parts of the bay; one dug in with a pickaxe; one made by damming a narrow exit to the sea from a hollow so that the dam held the pool behind it; and one by making a circular wall low down in the intertidal.

The foreshore belongs here to the Scottish crown, and so I got permission to do this first and then set about making the pools – wanting them to be cups of what I learned to call bio-receptivity – beginning with quite literally a rock-pool, an empty planetary space, and then waiting to see what the sea would deliver to them. An enlargement of the habitat. A tiny gesture to counteract the lack of accommodation we are all making for the natural world. In a way, no more than making sandcastles, but sandcastles that would invite their inhabitants in and would last more than a single tide.

Shorelines and rock pools are incredibly biodiverse environments; how did you decide which species to write about?

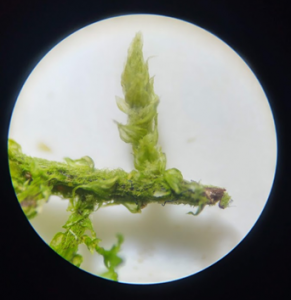

It was not about rarities. I thought for a while I should call the book ‘All the Usual Beauty’. And anyway the species selected themselves. I began at the top of the beach at the spring equinox, although there was not a hint of spring, when I started poking around in the seaweeds thrown up there by the winter storms. Nothing else seemed to be alive on this frozen March day, but lift away the lid of weed and quite literally the sandhoppers sprang into life around me. Again and again they went though their routine: leap, wriggle, play dead, leap, wriggle, play dead. Almost toy-like in their repetitions.

And so that provided the model – see what was there and look carefully at it. Of course, books like mine are entirely parasitic on the work of many generations of biologists and that too turned out to be the pattern. Watch the sand hoppers and then read about them. Read about them and see how much of what I read I could find on the shore. With prawns, winkles, shore crabs, anemones, limpets, sea-stars, urchins and barnacles, I simply oscillated between the pools and my books: what was there? What had people discovered about them? How did they interact? What were the principles governing their presence or absence? And with all of that came the repeated and slightly sobering realisation that unless I knew to look for something it was very difficult to see it was there. Mysteriously, we are often blind to what is in front of our eyes.

And so that provided the model – see what was there and look carefully at it. Of course, books like mine are entirely parasitic on the work of many generations of biologists and that too turned out to be the pattern. Watch the sand hoppers and then read about them. Read about them and see how much of what I read I could find on the shore. With prawns, winkles, shore crabs, anemones, limpets, sea-stars, urchins and barnacles, I simply oscillated between the pools and my books: what was there? What had people discovered about them? How did they interact? What were the principles governing their presence or absence? And with all of that came the repeated and slightly sobering realisation that unless I knew to look for something it was very difficult to see it was there. Mysteriously, we are often blind to what is in front of our eyes.

Did you discover anything particularly interesting that you were previously unaware of during your research?

So much! I never knew that sandhoppers could inherit from their parents an understanding of where the sea was and how to get there. That winkles can tell if a crab has been in their pool. That crabs, even in the tiniest of larval  stages, can recognise the movements and timings of the tides. That sea anemones can identify other sea anemones that are not their relations and effectively destroy them. That prawns have an imagination – that might sound like too much, but it has been shown that they can remember past pain and project it into present and future anxieties. Anxiety is different from fear; it is a fear of what might be there. In other words a prawn can think beyond its present reality.

stages, can recognise the movements and timings of the tides. That sea anemones can identify other sea anemones that are not their relations and effectively destroy them. That prawns have an imagination – that might sound like too much, but it has been shown that they can remember past pain and project it into present and future anxieties. Anxiety is different from fear; it is a fear of what might be there. In other words a prawn can think beyond its present reality.

Some of my most treasured childhood memories involve investigating Dorset shorelines and delighting in the incredible variety of species I would find there. What do you think it is about the shoreline that people connect with so strongly?

I think maybe the shore is so alluring because it is both so strange and so easily to hand. It is a revelation of another world a yard or two away from our own. The temptation is to think of the pool as a natural garden, but it is a very odd and very wild garden. Looking perhaps as settled and delicate as a painting but in fact a theatre and cockpit of competition and rivalry. And  garden whose walls are dissolved twice a day, an enclosure that becomes part of the general world with every high tide. That ambiguity is what entranced me, the sense of its being a micro-ocean, a micro-arcadia, a micro-laboratory in which all kinds of intimacies and precision in natural beings can be witnessed an inch beneath your nose.

garden whose walls are dissolved twice a day, an enclosure that becomes part of the general world with every high tide. That ambiguity is what entranced me, the sense of its being a micro-ocean, a micro-arcadia, a micro-laboratory in which all kinds of intimacies and precision in natural beings can be witnessed an inch beneath your nose.

Although adaptable, rocky shore inhabitants are not invincible, what do you think is the biggest threat to the rocky shore ecosystem and are some species more at risk than others?

Sea-level rise should not cause the inhabitants of rocky shores too many problems. They will climb the rocks in time with the water. But other anthropogenic effects are quite likely to be catastrophic. Animals that depend on their shell for protection are living in an increasingly hostile world. Everywhere in the North Atlantic outside Europe, as the Dutch evolutionary biologist Geerat J. Vermeij has written, an increase in shell thickness has been taken as a response ‘to the spread of the introduced European green crab (Carcinus maenas), but these changes may also have resulted from an overall increase in the abundance of native shell-crushing crabs (Cancer spp.) and lobsters (Homarus americanus) as the predators (including cod) of these crustaceans were overfished’.

The destruction of the cod and the collapse of their position as an apex predator in the Atlantic has made it a sea of claws. That hugely increased claw count, and competition between the clawed animals, has risen to the point where the shell-dwellers are feeling the pressure and have responded as shell-dwellers and shell-wearers must: by thickening their defences and toughening their lives.

But modern life has provided them with another hurdle: the acidification of the world ocean. One-third of all the carbon dioxide that has been emitted since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution has been absorbed by seawater, turning it acid. Making shells and skeletons, drawing calcium carbonate from the water, is more difficult in an acid sea. All kinds of ripple effects will spread out from that: more crabs, fewer winkles, denser algae and a disruption of the entire coastal ecosystem.

The effect is more than purely chemical. When sea-fish are exposed to acid water, their senses of smell and hearing are both disrupted. Young fish find it more difficult to learn, become less frightened by danger and are even attracted to the smell of predators. The same now seems to be true of shellfish. Acid water is distorting the minds of animals in the entire ecosystem.

Do you have any further projects or books in the pipeline?

I do! I am writing a long piece on English chalk-streams and also slowly researching a book about the birds in the wood at home. And I would love to write something one day about the mammals of the Scottish sea. Otters, seals, whales and dolphins. One day!

The Sea Is Not Made of Water

The Sea Is Not Made of Water

By: Adam Nicolson

Hardback | Due June 2021 | £16.99 £19.99

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

The

The

And most importantly – just go out there and watch mammals. I may be biased, but for me there is nothing better than being out in the countryside early on a spring morning watching the hares chasing around and knocking seven bells out of each other. You might like to stay up late watching badgers or bats, or enjoy the crazy antics of a squirrel on a bird feeder. It’s important that we engage with nature and encourage our children to do the same. If we don’t see and understand wildlife, we won’t fight for it. And, trust me, we need to fight for it.

And most importantly – just go out there and watch mammals. I may be biased, but for me there is nothing better than being out in the countryside early on a spring morning watching the hares chasing around and knocking seven bells out of each other. You might like to stay up late watching badgers or bats, or enjoy the crazy antics of a squirrel on a bird feeder. It’s important that we engage with nature and encourage our children to do the same. If we don’t see and understand wildlife, we won’t fight for it. And, trust me, we need to fight for it.

slow I would be overtaken by very old people on Zimmer frames. It seemed as though I’d hit 97 five decades prematurely.

slow I would be overtaken by very old people on Zimmer frames. It seemed as though I’d hit 97 five decades prematurely.

To the casual observer, global summits and the resolutions they produce can seem frustratingly ineffective – repeating cycles of targets set, missed and reset, with no obvious progress. Yet despite the apparent inertia, when used to good effect these processes can be powerful tools for positive change.

To the casual observer, global summits and the resolutions they produce can seem frustratingly ineffective – repeating cycles of targets set, missed and reset, with no obvious progress. Yet despite the apparent inertia, when used to good effect these processes can be powerful tools for positive change.  It’s hugely important. Not only do these treaties establish some of the most important conservation objectives, but they provide a means of learning from other experience. Typically, international treaties set a broad goal – such as ‘the wise use of wetlands’ in the case of the Ramsar Convention – but are much less prescriptive as to exactly how this will be delivered nationally. Accordingly, there is much to learn from the broad diversity of other national conservation experience in implementing treaty obligations. Such comparative experiences make these treaties fascinating and their study valuable.

It’s hugely important. Not only do these treaties establish some of the most important conservation objectives, but they provide a means of learning from other experience. Typically, international treaties set a broad goal – such as ‘the wise use of wetlands’ in the case of the Ramsar Convention – but are much less prescriptive as to exactly how this will be delivered nationally. Accordingly, there is much to learn from the broad diversity of other national conservation experience in implementing treaty obligations. Such comparative experiences make these treaties fascinating and their study valuable. Following on from the previous question, this book highlights the role and importance of NGOs (and a number of the authors themselves have been or are currently involved with NGOs). Do you think NGOs should have more involvement in environmental policy, both within the UK and on a global scale?

Following on from the previous question, this book highlights the role and importance of NGOs (and a number of the authors themselves have been or are currently involved with NGOs). Do you think NGOs should have more involvement in environmental policy, both within the UK and on a global scale?

James Lowen is an award-winning writer whose work is regularly featured in The Telegraph, BBC Wildlife and Nature’s Home, among other publications. He is also an editor, lecturer, consultant and keen photographer.

James Lowen is an award-winning writer whose work is regularly featured in The Telegraph, BBC Wildlife and Nature’s Home, among other publications. He is also an editor, lecturer, consultant and keen photographer.

fragile creatures flying a thousand-plus miles). There’s wackiness too: china-mark moths, whose caterpillars live underwater; Sandhill Rustic, whose adults can swim underwater; Scarce Silver-lines, which sings from oak trees; various moths that are engaged in an evolutionary arms race with bats; Indian Meal Moth and Wax Moth, whose caterpillars can digest polyethylene and polypropylene (perhaps conceivably hinting at a solution to the global plastics problem?); and even one New World moth whose cells have proved critical for producing the Novavax COVID vaccine.

fragile creatures flying a thousand-plus miles). There’s wackiness too: china-mark moths, whose caterpillars live underwater; Sandhill Rustic, whose adults can swim underwater; Scarce Silver-lines, which sings from oak trees; various moths that are engaged in an evolutionary arms race with bats; Indian Meal Moth and Wax Moth, whose caterpillars can digest polyethylene and polypropylene (perhaps conceivably hinting at a solution to the global plastics problem?); and even one New World moth whose cells have proved critical for producing the Novavax COVID vaccine. sun-loving, day-flying moth. I guess the other thing to emphasise is that whereas moth-trapping in your garden makes for gloriously lazy wildlife-watching, simply flick the switch and let the insects come to you, surveying moths in remote places is contrastingly hard work. After a long drive, often on the back of little sleep, you need to lug heavy generators and a fleet of moth traps up steep slopes or across difficult terrain. And then you need to stay alert all night to make sure you don’t miss anything. I didn’t get much sleep that year…

sun-loving, day-flying moth. I guess the other thing to emphasise is that whereas moth-trapping in your garden makes for gloriously lazy wildlife-watching, simply flick the switch and let the insects come to you, surveying moths in remote places is contrastingly hard work. After a long drive, often on the back of little sleep, you need to lug heavy generators and a fleet of moth traps up steep slopes or across difficult terrain. And then you need to stay alert all night to make sure you don’t miss anything. I didn’t get much sleep that year…  intrepid endeavours to safeguard

intrepid endeavours to safeguard