In the lead up to the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in November of last year, as well as the months that have followed, we have been writing a series of articles looking at some of the toughest global climate crisis challenges that we are currently facing. This article looks at the increase in frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, their impacts, and how they are affected by climate change.

What are extreme weather events and why do they occur?

Extreme weather events can be split into four categories: geophysical (i.e. tsunami), meteorological (i.e. storms, tornadoes), hydrological (i.e. floods) and climatological events (i.e. extreme temperatures, drought, wildfires). They are usually defined as unusual, unexpected, unseasonal or severe weather. This extreme weather often has a significant impact on us and the environment, causing damage, loss of livelihood and even loss of life.

There is debate as to how much climate change is responsible for our changing weather patterns. There are a variety of causes for extreme weather, including tectonic plate shifts, changes in air pressure or movement, ocean temperatures, atmospheric moisture content, the reflection rate of solar radiation and even the tilt and orbit of the Earth. These are natural variations that cause naturally occurring extreme weather, therefore, the occurrence or even intensity of these events cannot only be blamed on climate change.

How does climate change affect extreme weather events?

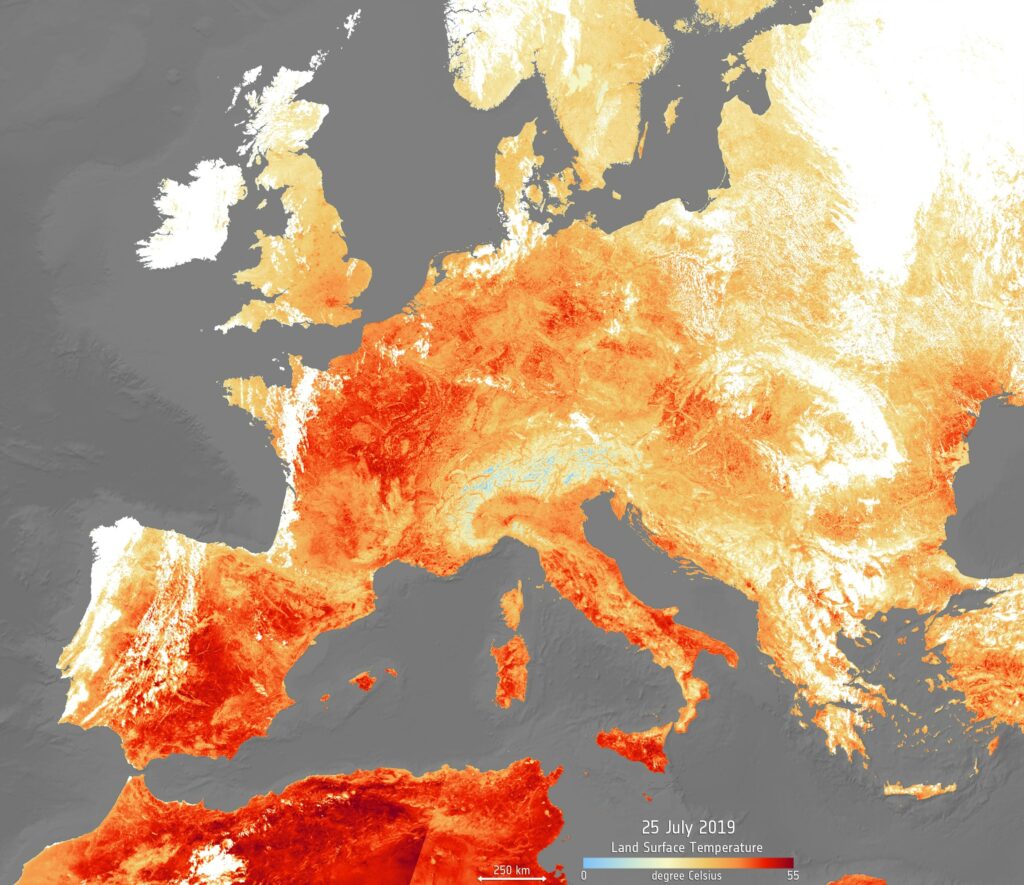

Many studies on weather events around the world have connected the increase in intensity and frequency of extreme heat, drought and rainfall to human influence. The picture is more complex for tropical storms (hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones). It is expected that these events will become more intense due to human influences, such as sea-level rise and anthropogenic warming. It is thought that these tropical storms will occur less frequently, however, although there is no consensus.

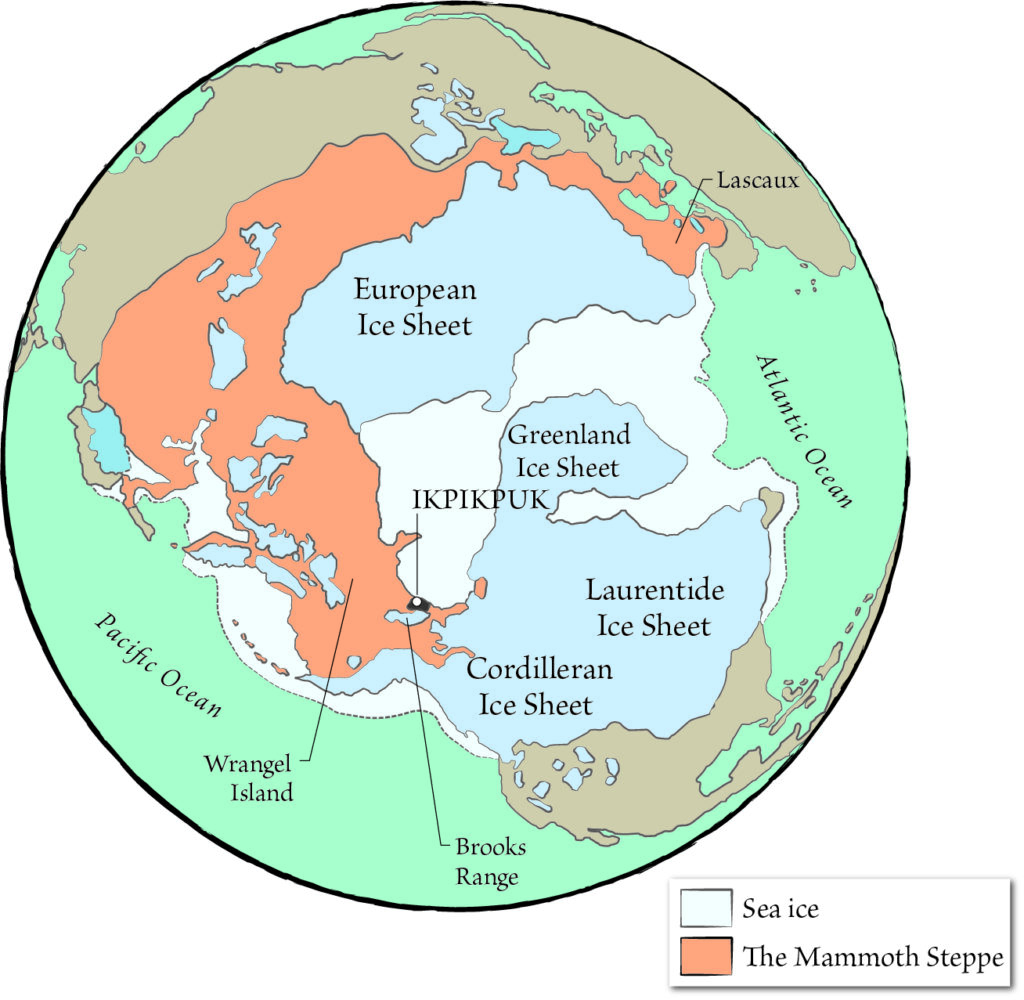

The increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide and greenhouse gases due to human activities is causing an increase in average global temperatures. This leads to other impacts, such as glacial and sea ice melting, which is affecting the global ocean circulation. This circulation acts as a conveyor belt, transporting cold water from the poles to the equator and warmer water and precipitation from the tropics back to the poles. A disrupted circulation, for instance due to the weakening of the Gulf Stream, could cause extreme weather events such as far colder winters in western Europe.

Actions such as deforestation can also cause changes in extreme weather events, as removing large sections of forest can impact the movement of water in the atmosphere. This can change precipitation patterns both locally and globally – if occurring on a large enough scale. Increased precipitation can cause flooding, whereas a decrease in rainfall can lead to drought. For more information, check out our previous Climate Challenges article on the local and global implications of deforestation and its relation to climate change.

What are the impacts of extreme weather events?

The damage from extreme weather events to both humans and the environment can be catastrophic. Beyond the direct loss of life, there is an impact on livelihoods, homes and other buildings, roads and infrastructure. The costs of these events can be incredibly high, and it can take years or even decades for areas and countries to recover from the worst of these events. This will only get worse as they become more intense and more frequent, as there will be more damage and less time to recover between events. During February of this year, a series of successive storms, including Dudley, Eunice and Franklin, brought widespread damage, leaving hundreds of thousands without power and millions of pounds in repair and clean-up costs.

Many cities are not built to withstand weather conditions outside of the norm for the area and, therefore, may not have the infrastructure in place to deal with certain extreme weather events. This was evident during the 2021 snowstorm in Texas, United States, where the state’s power supply was not equipped to deal with the record low temperatures. This led to many power outages for over 5 million people, with the total loss of life reported as 210 people.

Environmentally, habitats can be impacted. They can be altered or even destroyed, leading to the extinction of many species that are unable to rapidly adapt, particularly if their distribution is already restricted. It is usually generalist, resilient species that are able to adapt and survive this level of disturbance, therefore specialist species are more likely to become extinct. After a major disturbance event, ecological succession can take place and species recolonise the area. This phenomenon begins with pioneer species, such as plants, lichens or fungi, and the animals that rely on them, before developing in complexity to a stable ‘climax community’. This habitat can be vastly different from the original, depending on the species that survived the original event and those nearby that can recolonise the area. The climax community can also take decades or even centuries to develop, therefore the biodiversity of the area may be reduced or altered for an extended period of time.

What can be done?

Similarly to many of the climate challenges in this series, the solution relies on limiting the rise of global average temperatures. This can be achieved through a combination of methods, many of which were discussed at the COP26 in November 2021. Some of these methods, such as switching to renewable energies and moving towards more sustainable agriculture, are already underway in the UK.

More work needs to be done, however, as even the 1.5°C limit in the rise in global average temperature that the Paris Agreement is aiming for could still have a huge impact on the climate. At 1.5°C, 14% of the world’s population will be exposed to severe heatwaves at least every five years. Rainfall will become more erratic, leading to more flooding, droughts, and reduced water availability. Extreme weather events will be more likely to occur and at a higher intensity.

While the impacts of a 1.5°C rise are thought to be less than those of a 2°C rise, they will still be devastating to many countries and people. And so it is key that countries begin to build resilience against extreme weather, support those most vulnerable and begin to protect and restore habitats. Countries were asked to produce an ‘adaptation communication’ for COP26, outlining what they are currently doing and their future plans to adapt to the impacts of climate change.

COP26 pledges

Following COP26, 90% of the world’s economy is now striving for net zero emissions, with many aiming for 2050; over 100 world leaders signed both The Glasgow Leader’s Declaration on Forest and Land Use and the Global Methane Pledge; and more than 40 countries signed the Coal Pledge, which aims for nations to move away from coal power by the 2030s for major economies and 2040s for developing countries. In addition, multiple countries, companies, philanthropic foundations and international development banks pledged funding to move away from financing fossil fuels and towards renewable energies.

While there are a number of faults with some of these pledges, with criticism over the perceived lack of strict accountability, a peer-reviewed study has found that these new policies could help to keep global warming below 2°C. This will hopefully limit the impact of climate change on extreme weather events, but to keep within the target of 1.5°C, far more needs to be done. The IPCC announced that emissions would need to peak before 2025 and significantly decline by 2030. Read more about the outcomes of COP26 in our blog: Climate Challenges: COP26 Round Up.

Summary

- Extreme weather events are unusual, unexpected, unseasonal or severe weather. They can cause massive damage and destruction to both us and the environment.

- Due to climate change, many extreme weather events may become more frequent and more intense. This will cause more damage and allow less time to recover, potentially pushing both communities and ecosystems beyond the point they can survive.

- The solutions rely on reducing the rise in global average temperatures by reducing the amount of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere.

Even at a rise of 1.5 degrees, the impact of extreme weather could increase. Therefore, a strategy of adaptation and protection for those most vulnerable is needed. - The policies and pledges signed at COP26 last year may be enough to keep global average temperatures below 2°C, but far more is needed to limit the rise to 1.5°C.

Useful resources:

The COP26 website page on their goal of adaptation: https://ukcop26.org/cop26-goals/adaptation/

NASA’s website on selected findings of the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming, highlighting the impacts of a 1.5°C versus 2°C rise. https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2865/a-degree-of-concern-why-global-temperatures-matter/

Our previous blog on Climate Challenges: What is COP26 and Why is it Important?, covering many of the impacts of an increase in global average temperatures above 2°C and the goals of the UK government.

Water Always Wins: Going with the Flow to Thrive in the Age of Droughts, Floods & Climate Change

Erica Gies

Available for pre-order | Hardback | £19.99

Drought, Flood, Fire: How Climate Change Contributes to Catastrophes

Drought, Flood, Fire: How Climate Change Contributes to Catastrophes

Chris Funk

Hardback | £19.99

Angry Weather: Heat Waves, Floods, Storms, and the New Science of Climate Change

Angry Weather: Heat Waves, Floods, Storms, and the New Science of Climate Change

Friederike Otto

Hardback | £18.99

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

I was originally studying how birds might choose their mates on the basis of certain immune genes, following the idea that animals could prefer mates with different genes than their own, leading to offspring with stronger immune systems. I was struggling to sequence these genes, and I complained to a colleague who happened to be studying bird brains. He said, “I don’t know why you’d study that in birds – information about those genes is sensed by smell, and birds don’t have much of a sense of smell.” I had never heard that before, and the idea that a whole group of animals would lack such an important sense seemed absurd to me. So, I started investigating.

I was originally studying how birds might choose their mates on the basis of certain immune genes, following the idea that animals could prefer mates with different genes than their own, leading to offspring with stronger immune systems. I was struggling to sequence these genes, and I complained to a colleague who happened to be studying bird brains. He said, “I don’t know why you’d study that in birds – information about those genes is sensed by smell, and birds don’t have much of a sense of smell.” I had never heard that before, and the idea that a whole group of animals would lack such an important sense seemed absurd to me. So, I started investigating.