The National Biodiversity Network Trust has been supporting the sharing of wildlife data since 2000. The trust consists of over 200 members, ranging from world renowned organisations to individual enthusiasts and there are now more than 300 million wildlife records available through the NBN Atlas.

Mandy Henshall, communications and engagement manager for NBN tells NHBS about the early days of the trust, achievements so far, how you can get involved and their hopes for the next 25 years.

How did the NBN Trust come into being in 2000?

It might come as a surprise, but there’s never been a legal requirement for any one organisation to collect or manage biological records over the long term.

Despite, or because of this, the Biological Records Centre (BRC) was set up in 1964 to bring together data, mostly from volunteer recording groups, share it with conservation organisations and publish the findings.

The BRC has done a brilliant job, but without a joined-up approach or enough resources to support both local and national recorders, no single organisation could get a full picture of what was going on. As the need to report on environmental issues grew, so did the pressure to make data more accessible.

The push to create the National Biodiversity Network (NBN) came from the Biodiversity Action Planning process, which followed the 1992 Rio Summit. A report from the Coordinating Commission for Biological Recording helped bring together UK organisations in 1997 to pool their efforts and make sharing data easier.

That’s how the NBN Trust came to be. It was set up as an independent charity in 2000 to help build and support the Network.

If you want to delve a little deeper, you can find out more about our story and our founding members on the NBN Trust website.

What was the early work focused on?

In the beginning, the focus was all about getting things off the ground and developing projects and activities that would help move the NBN Trust forward and support the wider Network. Some of the key things we worked on included:

- Creating a shared set of principles for how data should be exchanged

- Hosting an annual Conference to bring people together, share ideas, and build connections across the partnership

- Launching the NBN Gateway — the first online platform for sharing biodiversity data (this was replaced by the NBN Atlas in 2017)

- Building the Species Dictionary (now called the UK Species Inventory – UKSI) in 2003, which enabled data to be indexed and searched

- Producing guidance on everything from managing and sharing data to handling sensitive information and intellectual property rights, so that data could be used more freely and confidently

- Creating mapping resources to support better mapping and recording

Much of this is still central to our work today.

What has been the biggest change for the NBN Trust and wildlife recording since 2000?

There have been two major changes over the years:

- The first is all about technology, specifically the launch of the NBN Atlas in 2017. This platform is based on the Atlas for Living Australia and was built to handle the growing amount of data being shared. When we moved from the NBN Gateway, we were making 117 million records available. Now, the NBN Atlas holds over 300 million species records, so almost double. Downloads have also increased significantly, with over 1 billion records downloaded by the end of 2024.

- The second big change is how much easier it has become for anyone to record and share wildlife sightings. Thanks to apps and websites like iNaturalistUK, iRecord, and other platforms, many more people are getting involved. This new and accessible technology helps to standardise record collection and gather more valuable data, from experts and citizen scientists alike, which can be used to protect and restore nature.

Looking ahead: What might the next 25 years hold for the NBN Trust?

Undoubtedly, technology will continue to keep evolving and changing how we record and share biodiversity data. We’ve already started seeing this with the rise of environmental-derived DNA (eDNA) datasets on the NBN Atlas, and that’s only going to grow. We’ve made big upgrades to the Atlas to keep up with technological advances and the sheer volume of data, and we’ll need to keep adapting as new tools and techniques come along.

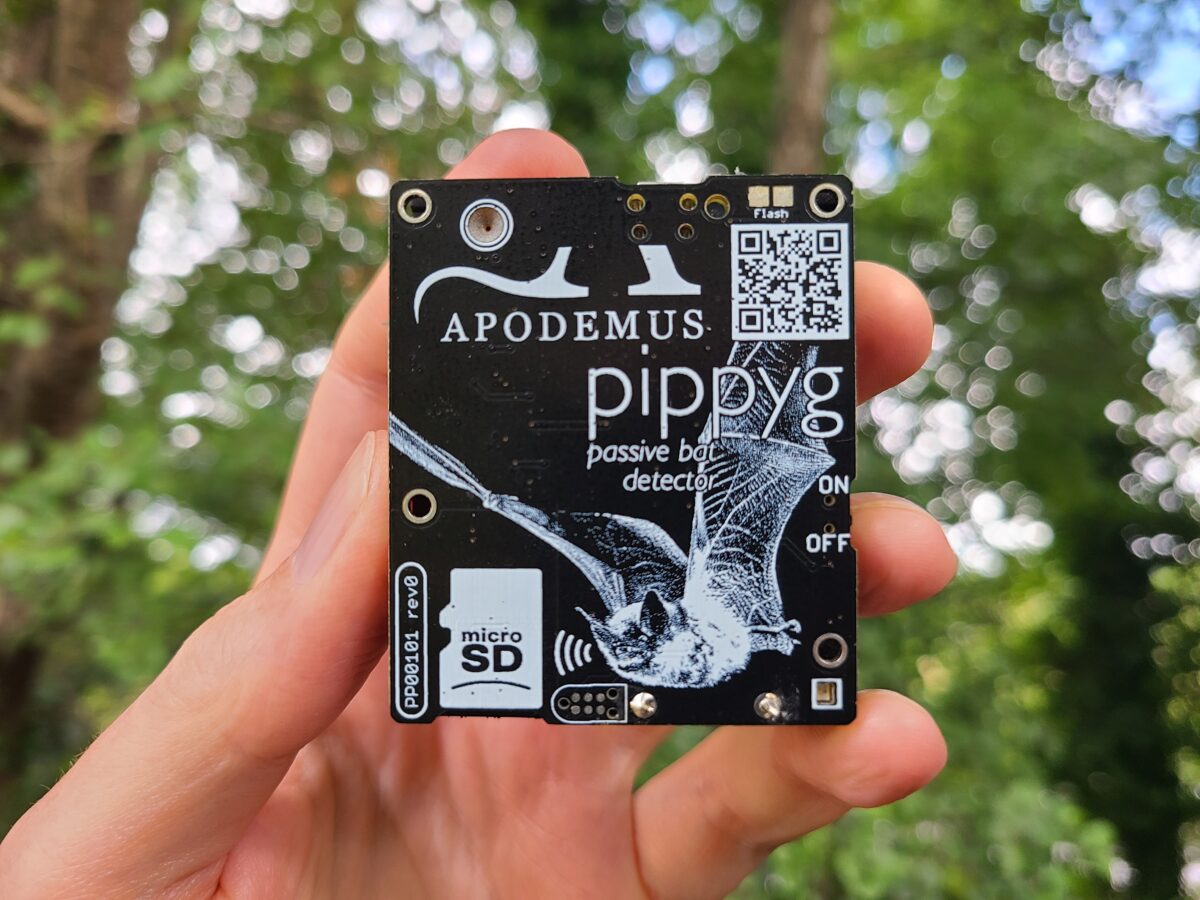

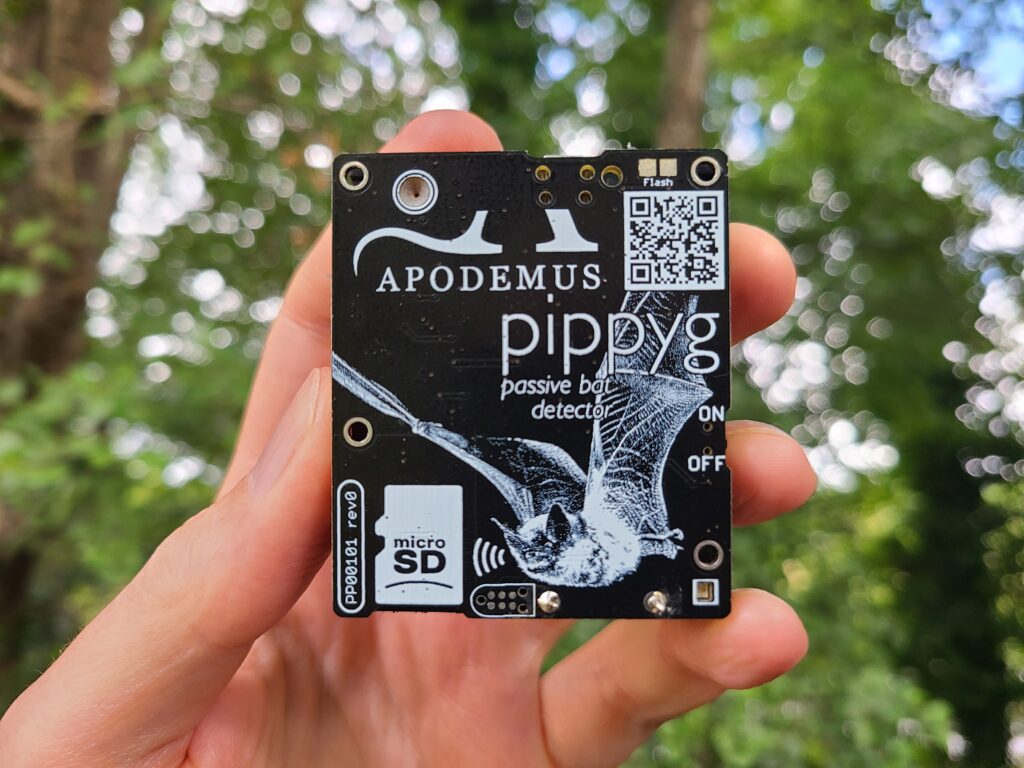

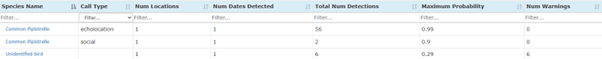

We might also see more automated data collection, like AI-powered species identification from photos or sounds, and even drones or remote sensors helping to monitor habitats in real time. These kinds of innovations could make recording faster, more accurate, and accessible to even more people.

It’s not just about technology though, who we engage with in the future will be crucial to our success. We’d like to increase our impact and our mission by working not only with data collectors, academics, and policy makers, but also with businesses, financial institutions, and the private sector all of whom have a crucial role to play in tackling the planetary emergencies through data, collaboration, and investment in nature. This will be a key change for us, but one which is really exciting.

Despite these broader changes, the heart of the Network will still be the recorders: the volunteers, the citizen scientists, and the organisations who collect, share and verify data. Without them, there wouldn’t be an NBN Atlas, or a National Biodiversity Network.

So, as we celebrate being 25, we’d like to say a huge thank you to everyone who’s part of the NBN community. Whether you’re a member of or donor to the NBN Trust, a partner in the NBN, a data provider to the NBN Atlas, or someone who’s just started recording wildlife – you’re helping us to make data work for nature.

How can people get involved?

We’ve already talked about the importance of people and data to the Network, so one really important activity for people to do is to record the wildlife they see and to share the details. We’ve got information about this on the website – https://nbn.org.uk/record-share-explore-data/record-wildlife-a-fun-way-to-help-nature/

We have our annual NBN Conference on 20th November in Bristol. This will be themed around our 25 years anniversary and will delve into the past, present and future of the NBN. It’s also a great occasion to come together and celebrate the amazing people already recording nature through the NBN Awards for Wildlife Recording. The Awards’ shortlist can be found here and NHBS is one of our generous sponsors.

Finally, as a UK registered-charity, income generated from our donations and partnerships helps fund our vital work supporting the whole UK nature recovery sector with wildlife data.

We’re nothing without our members, supporters and donors and we’re grateful to every individual and organisation that contributes to our work. If you would like a future where nature is thriving everywhere, in all its diversity, please consider a donation. Every penny will go directly to our work – to make data work for nature. Thank you. https://nbn.org.uk/support-us/