NHBS is working with the Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology (LIST), as part of the Camphibian Project, to help develop a novel approach that will improve amphibian monitoring using NEWTCAM, an underwater camera device. The Camphibian Project continues to improve and test the NEWTCAM to assess its value for biodiversity monitoring.

The problem

Amphibian species are facing global decline, due to a range of factors including climate change, habitat loss, infectious disease, and environmental contamination. As an important species group showing steep declines worldwide, amphibians are frequently used as biodiversity indicators, but our ability to document changes in amphibian population sizes and community structures is limited. Current methods for surveying and monitoring newts, such as eDNA, bottle trapping, netting and torching, are either unable to produce accurate population size estimates or very invasive, frequently risking the health of individuals. Furthermore, these methods can be weather dependant, as certain conditions, such as heavy rain or temperatures above or below optimal levels lead to surveys being called off. Reliable survey and monitoring methods are essential for assessing changes in populations and ecological communities, data which feed into environmental research and policy support.

The concept

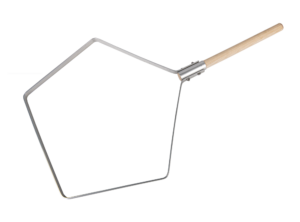

The automation of field observations has been improved in recent years with the development of camera traps, but to date there has been no viable aquatic camera trap. The NEWTCAM (originally developed as the Newtrap) is an open underwater tunnel with an integrated camera and lighting system that automatically captures high resolution time series of standardised images of aquatic animals. The NEWTCAM can be left unattended in the water for several days because the animals are free to enter and exit the NEWTCAM and are not captured or handled in any way, greatly improving survey effort, detection rates, and reducing stress on the animals.

In common with all camera traps the NEWTCAM produces 1000s of images and/or videos. These are managed with the NEWTCAM Manager (a separate web application) which supports all the steps of image processing by:

- Enabling the centralisation of data from multiple NEWTCAM devices, survey sites, projects, and even organisations.

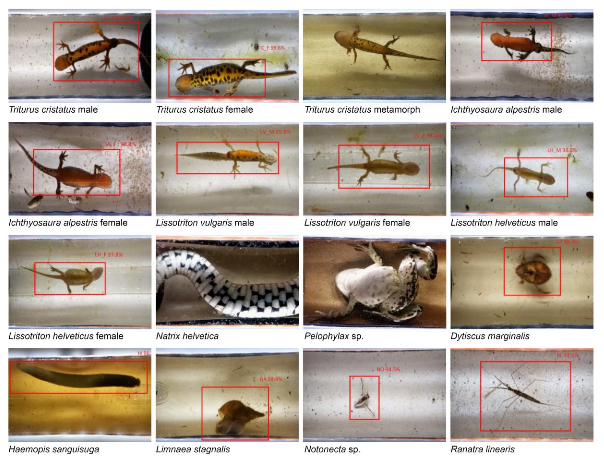

- The annotation of images and videos by species, stage, gender, and behaviour. The data can then be used as a reference image library to train a new AI algorithm or processed with an appropriate existing identification algorithm (for more information see RCNN).

In future, existing AI algorithms (e.g. for newts in North Western Europe) will be integrated into NEWTCAM Manager, enabling the analysis of data sets.

Standardisation

The NEWTCAM takes standardised images from a predetermined angle, for example the underside of a newt (or other target species), from which the species, sex, development stage, body measurements, and individual identification (if individual variation exists, such as the irregular pattern of dark spots on the underside of great crested newts) can be determined. This data can then be used to provide important information about the presence, population size and dynamics of the species or communities of interest.

Benefits when compared to traditional survey methods:

- Reduced disturbance to sensitive habitats because the NEWTCAM is placed in situ once, but can then record data for weeks or months.

- Zero handling of individuals because the NEWTCAM is an open tunnel that allows individuals to enter and exit at will.

- Reduced number of site visits compared to bottle trapping, netting, and torching.

- Easy deployment in the field meaning that more sites can be surveyed over a longer period and with a higher temporal resolution than when using standard methods.

- Standardised field observations – the NEWTCAM will enable the development of improved AI-based processing methods and their centralisation to produce well-formatted databases for large-scale and global change studies because the cameras produce images with the same size, resolution, background, specimen position and illumination.

- The potential to provide accurate population estimates through the identification of individuals (where individuating marking exist).

- Greater freedom to place the NEWTCAM at different sites and depths throughout the water body.

- Surveys can be carried out in adverse weather conditions including heat waves and heavy rain.

- The orientation of the NEWTCAM can be changed so that different target species can be filmed from different angles.

The Camphibian Project

The Camphibian Project – has two main aims, to improve the functionality, durability and versatility of the NEWTCAM and to assess its value as a user-friendly freshwater wildlife monitoring method.

These aims will be accomplished through a programme of technological development work at LISTs laboratories and the NHBS workshop followed by a series of field experiments conducted by LIST and early user field trials. These experiments will assess:

- Whether NEWTCAM offers a reliable and robust approach for detecting and estimating the population size and dynamics of a wide range of amphibian species.

- The NEWTCAMs ability to detect a range of different species and life stages in a wide variety of habitats.

- Whether the data produced by the NEWTCAM is sufficient to produce reliable population estimates for species with individuating patterns at the larval stage.

As the NEWTCAM is developed, there will be opportunities for ecologists to test the equipment and the NEWTCAM will be displayed at conferences and events (details to be confirmed). If you would like to find out more, please sign up to our mailing list.

NHBS is providing funding alongside Fonds National de la Recherche Luxembourg, and LIST (Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology).

NHBS is providing funding alongside Fonds National de la Recherche Luxembourg and LIST (Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology).

Wooden bat boxes

Wooden bat boxes  Woodstone and woodcrete bat boxes

Woodstone and woodcrete bat boxes Eco-plastic bat boxes

Eco-plastic bat boxes

There are also pole-mounted bat boxes (sometimes known as rocket boxes). These bat boxes are helpful alternatives in areas where there is nowhere to mount the bat box. An additional benefit is that they ensure that the bat box gains maximum sunlight in shaded areas.

There are also pole-mounted bat boxes (sometimes known as rocket boxes). These bat boxes are helpful alternatives in areas where there is nowhere to mount the bat box. An additional benefit is that they ensure that the bat box gains maximum sunlight in shaded areas. Lastly, there are bat roost access titles and bricks. These are designed to provide bats with access points within roof or ridge tiles. Some bats will roost in the confined spaces beneath the tiles and others will use the open roof space to roost.

Lastly, there are bat roost access titles and bricks. These are designed to provide bats with access points within roof or ridge tiles. Some bats will roost in the confined spaces beneath the tiles and others will use the open roof space to roost.

Alick Simmons is a veterinarian and a naturalist. During a career spanning 35 years he held the position of the UK Government’s Deputy Chief Veterinary Officer (2007-2016) and the UK Food Standards Agency’s Veterinary Director (2004-2007). In 2015 he began conservation volunteering, and has been involved in survey projects for both waders and cranes. He is currently chair of the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare and the Humane Slaughter Association. He also serves as a Trustee of the Dorset Wildlife Trust and chairs the EPIC disease control steering group on behalf of the Scottish Government.

Alick Simmons is a veterinarian and a naturalist. During a career spanning 35 years he held the position of the UK Government’s Deputy Chief Veterinary Officer (2007-2016) and the UK Food Standards Agency’s Veterinary Director (2004-2007). In 2015 he began conservation volunteering, and has been involved in survey projects for both waders and cranes. He is currently chair of the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare and the Humane Slaughter Association. He also serves as a Trustee of the Dorset Wildlife Trust and chairs the EPIC disease control steering group on behalf of the Scottish Government.