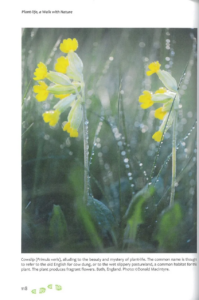

This adventurous and versatile book explores the wonders of our relationship with plants and our involvement with nature. Full of information on botanical science, ecological and environmental factors, artistic appreciation and philosophical reflection, Plant-Life offers a more holistic view of nature than in other books within this field. The text is supported by detailed images, diagrams and tables which provide a framework of understanding for the critical and questioning mind needed to approach biodiversity and climate change.

This adventurous and versatile book explores the wonders of our relationship with plants and our involvement with nature. Full of information on botanical science, ecological and environmental factors, artistic appreciation and philosophical reflection, Plant-Life offers a more holistic view of nature than in other books within this field. The text is supported by detailed images, diagrams and tables which provide a framework of understanding for the critical and questioning mind needed to approach biodiversity and climate change.

Author Edward Bent’s career was founded on a Botany degree from the University of Hull, followed by many years of experience spent working across different sectors, including research, marketing and education. After moving to Italy, he became a self-employed consultant and writer with many of his articles published in leading international publications, as well as a founding director of UK plant breeding company Floranova Ltd. While producing a series of botanical art compositions exploring spatial relationships in plant communities, Edward was inspired to research and write this book as a way of reflecting on his understanding of plants and the ways of nature.

Edward recently took the time out of his busy schedule to talk to us about the inspiration behind his book, why he chose to write in a journalistic style, other projects he’s currently working on, and more.

In the first chapter it says that you have always wanted to explore the beauty of plants and flowers and to share an appreciation of their world with others. How did you first develop this fascination and love of botany?

From an early age I liked to draw and paint plants and flowers to express an artistic temperament and reveal what I thought to be aesthetically pleasing. This extended to outdoor landscapes. At secondary school, I studied botany at ‘O’ and ‘A’ levels, followed by a degree course at University. During these scientific studies, significant periods of practical work allowed greater awareness of the beauty of plants and flowers and led me to make drawings. This same awareness continued through research and teaching, in parallel with a scientific frame of mind. I refer later to the influence of realising botanical compositions of wildflower communities while retaining a botanical coherence.

A dichotomous key was one of the first methods used to identify different plant species and variants through a hand lens before pictorial guides were developed. How do you think this early identification technique has affected the ways in which we observe and identify plants in the present day?

Pictorial guides to identify plant species represent a very useful shortcut, but, in many cases, just a few characteristics such as flower type, colour and leaf shape are sufficient to get the answer. While most guides also carry some detailed written descriptions, this is not commonly referred to except for professional reasons or uncertainty. The methodology of using a dichotomous key not only requires more time, but also attentive observation of far more plant characteristics. This helps develop powers of observation, or a trained eye, and better understanding of taxonomy, while providing an enjoyable sense of investigation. I believe that pictorial guides were developed to speed up the process of identification and to provide ordinary people, not just botanists, with an easier-to-use instrument.

I really enjoyed how Plant-Life touched on the relationship between botany and other disciplines such as art, poetry, maths and bio-economics. What inspired you to investigate these relationships throughout the book?

Firstly, reading Keith Critchlow’s book (see my answer to your question six), but also because of the impressions perceived of the beauty of spatial relationships in natural plant communities, through observation and realising the botanical compositions from pressed plant material. The aspect of bio-economics relates to the common denominator of chaos and complexity. Some years ago, I had also written another book that had prepared my mind to be more receptive to these relationships, and gave rise to my logo/trademark WOW – Walk on the Wild side.

When walking in the country, I always sought the big picture, since nature – of which we are part – is more than just the science. The concept of ‘Art of nature and Nature of art’ also came through in my research, strengthening the wish to break down perceived barriers between science, art and indeed philosophy. Scientific methodology works through separation, not only between different disciplines but also within them, while an examination of nature demands a more holistic approach.

What inspired you to write in a holistic, journalistic style rather than the more traditional, academic style that many ecology books demonstrate?

I think a holistic style is essential to understanding the ways of nature. It involved a strong desire to engage in artistic appreciation and philosophical/spiritual reflection on the perceived beauty of plants and wildflowers in their natural habitats. That is something I have, as long as I can remember, ‘taken aboard’ with a mixture of interest, observation and empathy. The artwork involved in the realisation of a series of botanical compositions also inspired the book and gave rise to logo, N-ART-URA – The Culture of Biodiversity.

A journalistic style in communicating information in straightforward language was obligatory after analysing big data – scientific papers, news releases, books etc – to make the writing more accessible to a wider and multi-level readership. This mission and ability stems from teaching and years of writing feature articles for the horticultural trade press and a few books. Equally, easier, pre-digested science would be unable to deal with some of the concepts and information presented in my book.

Do you think our plant life will reach a point where species will consistently be able to adapt to, and thrive within, the ever-changing environment that human activities have created?

Much depends on the timeframe. Our destruction of ecosystems can be total or partial (leaving intact corridors) and usually happens very quickly, whereas the process of plant adaptation is gradual and long drawn out. The protection and conservation of large areas of wilderness are fundamental to securing the absence of damaging human activities. Despite this, nature is programmed to fill any ecological voids that occur.

The so-called ‘generalist’ plant species adapt far more quickly to new environmental challenges, as opposed to more specialist species adapted to precise habitats, such as alpine flora . The latter have a much smaller gene pool when needing to adapt to new conditions, rendering them more vulnerable to extinction. So, the generalist species will adapt more quicky and spread more widely throughout areas of ecological disruption and damage caused by human activity.

Species distributions will become increasingly alike between different geographical areas and continents, caused by human activities – travel and transport, for example. There will be new opportunities for hybridisation, mutation and a few new species or sub-species. In a few cases, plant breeding and genetic manipulation in agricultural and horticultural crops, can ‘escape’, potentially affecting wild species from which crops were developed.

How did you develop your Holistic Notion diagram and what can this teach us about the relationship between nature and human emotions?

This diagram is central to my book and needs further development. The publication The Hidden Geometry of Nature (Floris Books) by the late Keith Critchlow was inspirational and highly informative in providing links to further thought and research. I highly recommend this important book to students and teachers of botany to give the subject a wider context.

The human mind reasons and analyses, whereas the human heart brings natural phenomena together, connecting with natural beauty; something that is impracticable in scientific study, because scientific methodology invariably needs to be separate. The Holistic Notion diagram seeks to present mathematical principles lying behind nature and the universe that translate to specific aspects of ‘being’, the substance of what we are and what we see. In holism, emotions and intuition are as important as the science in terms of understanding. Emotions stem from our interest and perception of form and substance, engendering a feeling of continuity and gratitude.

You briefly touched on the role of computers and artificial intelligence in creating ecological models that can be used to analyse data and potentially assist in the recovery of our environment. How important do you think these technologies will be in this process?

I believe that artificial intelligence and computer power will be very important in realising ecological models because of the huge amount of data and number of variables involved. What is less certain is the success of these instruments in terms of conservation or rewilding, because the whole picture can never be pinned down to one moment in time. Plant-life and nature are in constant evolution, even more so with the dramatic effects of climate change. I define nature as working through dynamic instability, choosing complementary interdependence as the means. So, recovery will depend on the progressive ‘load’ of environmental challenges on plant communities, the biosphere and the Earth system itself, caused by climate change. Just how can artificial intelligence predict these events?

Do you have any current projects in progress that you can share with us?

I am seeking ways to complete my NARTURA project by printing and publishing a series of nine botanical compositions, because earlier samples were well-received and complement the book. It requires, a printer, marketing, and distribution located in the UK. Living in Italy makes this more difficult, although I do have digital samples and plenty of ideas.

Edward Bent’s book Plant-Life, a Walk with Nature was privately published and is available on the NHBS website at Plant-Life: A Walk with Nature | NHBS Good Reads

Edward Bent’s book Plant-Life, a Walk with Nature was privately published and is available on the NHBS website at Plant-Life: A Walk with Nature | NHBS Good Reads

Kite Ursus Binoculars

Kite Ursus Binoculars GPO PASSION 10×32 ED Binoculars

GPO PASSION 10×32 ED Binoculars

In 1993,

In 1993,

My basic field kit apart from my wellington or gumboots, comprises a 30µm plankton net as seen in this photo, a basting pipette for mud surface collection, several numbered, wide

My basic field kit apart from my wellington or gumboots, comprises a 30µm plankton net as seen in this photo, a basting pipette for mud surface collection, several numbered, wide

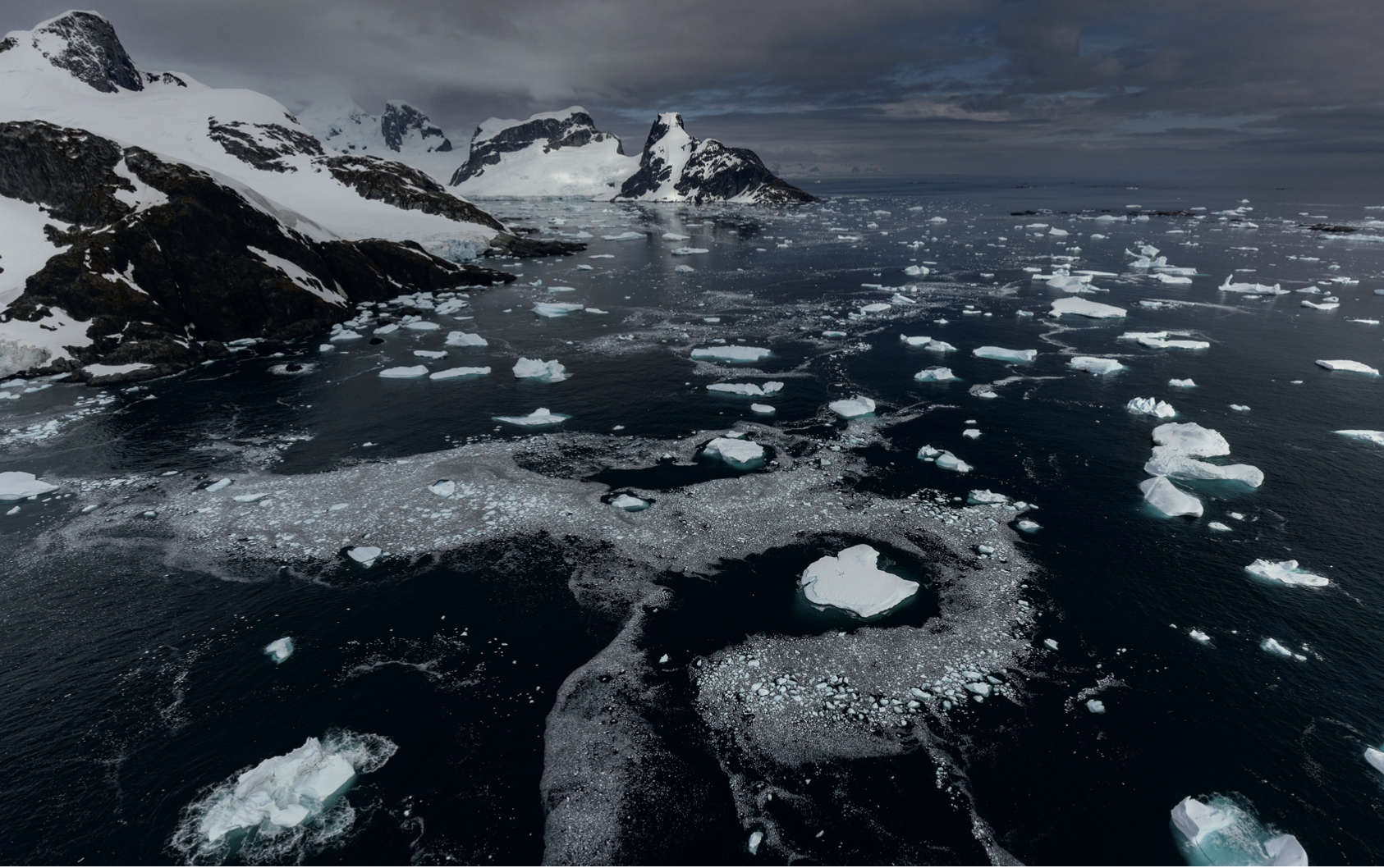

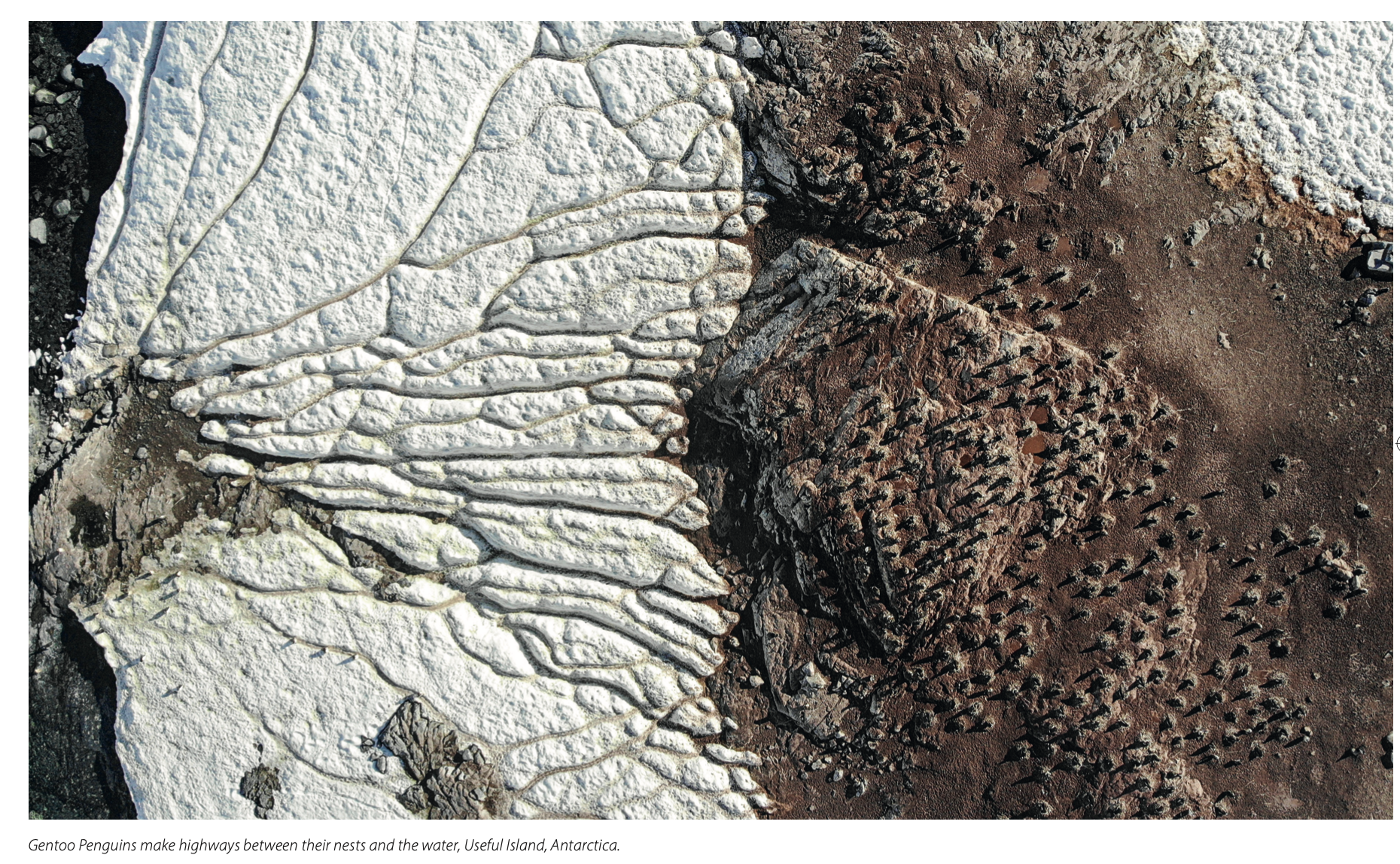

This stunning photographic book, written in collaboration with penguinologist Dr Tom Hart, offers a unique view of Antarctica from above and captures the wonders of this magical place, from vast icebergs to penguin colonies in their thousands. Each chapter includes an array of incredible captioned images, taken from both land and air, and describes the resident wildlife and conservation efforts in this remote area.

This stunning photographic book, written in collaboration with penguinologist Dr Tom Hart, offers a unique view of Antarctica from above and captures the wonders of this magical place, from vast icebergs to penguin colonies in their thousands. Each chapter includes an array of incredible captioned images, taken from both land and air, and describes the resident wildlife and conservation efforts in this remote area.

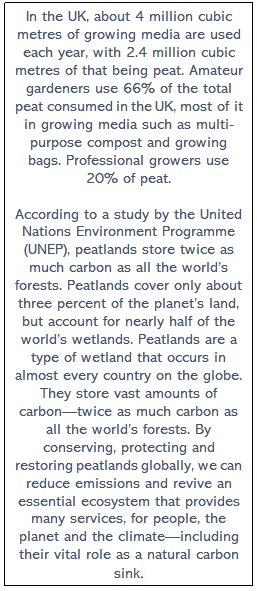

Proper Job in Chagford, Devon, is a registered charity that aims to protect and preserve the environment by promoting waste reduction, re-use and recycling. Its roots wriggle all the way back to 1993 when a group of environmentally conscious allotment holders launched a community composting project. They had noticed how much reusable, recyclable and compostable material was being dumped in the rural skip and started collecting anything that could be reused or recycled. In 1995, this resulted in the founding of a community business that was committed to principles of sustainability and the creation of jobs.

Proper Job in Chagford, Devon, is a registered charity that aims to protect and preserve the environment by promoting waste reduction, re-use and recycling. Its roots wriggle all the way back to 1993 when a group of environmentally conscious allotment holders launched a community composting project. They had noticed how much reusable, recyclable and compostable material was being dumped in the rural skip and started collecting anything that could be reused or recycled. In 1995, this resulted in the founding of a community business that was committed to principles of sustainability and the creation of jobs.