Big, messy and mysterious – crossing paths with a Wild Boar can conjure fear and joy in equal measure. In Groundbreakers, Chantal Lyons gets up close and personal with this complex and intelligent species in the Forest of Dean, and investigates the people across Britain and beyond who celebrate the presence of these animals – or want them gone. From Toulouse and Barcelona where they are growing in number and boldness, to the woods of Kent and Sussex where they are fading away, to Inverness-shire where rewilders welcome them, join Chantal on a journey of discovery as she reveals what it might take for us to coexist with the magnificent Wild Boar.

Big, messy and mysterious – crossing paths with a Wild Boar can conjure fear and joy in equal measure. In Groundbreakers, Chantal Lyons gets up close and personal with this complex and intelligent species in the Forest of Dean, and investigates the people across Britain and beyond who celebrate the presence of these animals – or want them gone. From Toulouse and Barcelona where they are growing in number and boldness, to the woods of Kent and Sussex where they are fading away, to Inverness-shire where rewilders welcome them, join Chantal on a journey of discovery as she reveals what it might take for us to coexist with the magnificent Wild Boar.

Chantal Lyons is a naturalist, writer and science communicator. Having grown up in the tidy countryside of Kent, her encounters with the growing rewilding movement opened her eyes to the potential for restoring nature in Britain, and inspired her to study the relations between people and Wild Boar in the Forest of Dean. She currently lives in Cheltenham, never too far from the boar.

Chantal Lyons is a naturalist, writer and science communicator. Having grown up in the tidy countryside of Kent, her encounters with the growing rewilding movement opened her eyes to the potential for restoring nature in Britain, and inspired her to study the relations between people and Wild Boar in the Forest of Dean. She currently lives in Cheltenham, never too far from the boar.

Chantal recently took time out of her busy schedule to tell us about her first experience with a Wild Boar, her hopes and fears for the future of their populations in Britain, and more.

First of all, could you tell us a little bit about yourself and what led you to writing a book about Wild Boar in Britain?

Up until my mid-twenties I spent all my writing time churning out unpublishable fantasy and sci-fi novels, alongside a zig-zagging career in the charity sector. The journey to Groundbreakers was perhaps a ponderous one – it started when I went to the Forest of Dean in summer 2014 to research a Masters dissertation in environmental social science. The Forest of Dean was, and still is, one of the few places in the country where Wild Boar have returned since their extirpation from Britain around 700 years ago. I wanted to find out from local residents what it was like to suddenly find yourself living alongside a big, wild, and utterly unfamiliar creature. What I discovered from those interviews astounded me, and I was sure that some established nature writer would soon publish a book about the return of boar to Britain and what this meant for us. No one did. After seven years, I decided to send off a proposal to a publisher who I’d encountered on Twitter, and it snowballed from there.

Could you tell us about your first real life experience with a Wild Boar?

It was a long time in coming! While I was in the Forest of Dean doing the Masters research, I used every spare moment to explore the woods on my own, often following locals’ leads. It always came to nothing. The boar seem to be like cats – you seem to be more likely to meet them the less you want to. But eventually, at the tail end of summer, I went to a spot where I’d heard from someone that a sounder (a family group of boar, which is always led by a matriarch) had been foraging each evening. I heard them softly calling to each other, then there was a rustling in the bracken, and an adult stepped out onto the path to get a look at me. We stared at each other for about two seconds, she gave a belching alarm call, and then she vanished with her family.

I appreciated the ways in which you speak about rewilding, in particular the importance of nuance and accepting the unknown. Do you think that uncertainties about the best way to undergo reintroduction projects and their expected outcomes are a significant hindrance to their implementation?

I have heard many a time from rewilding practitioners that the inherent uncertainties in rewilding can make it especially challenging to gain funding, given that projects aimed at restoring nature have traditionally been expected to be able to set clear targets and end-goals. But beyond practicalities like money, I think the bigger challenge is the attitude that reintroducing species for rewilding purposes is too big an unknown, and therefore too big a risk. Of course we should aim to conduct as much scientific research and gather as much knowledge as possible, but we are running out of time to reverse the haemorrhaging of our biodiversity in Britain and globally. To me, it beggars belief that we seem quite happy to continue doing all kinds of things that we know are massively damaging the environment, but reintroducing species? Why, that’s a step too far!

One part of the book that particularly resonated with me was in ‘The Risks of Being Alive’ where you speak about how, for most modern humans, ‘nothing matters more in life than eliminating all risk to it – even at the cost of happiness’. What do you think it would take for humans to accept more wildness into their lives?

Maybe it’s a cliché to say this, but I think it hugely helps to engage children with nature from a young age, and to continue doing so as they grow up. That of course means ensuring that everyone can access nature.

Beyond that, the question of how to convince people to accept more wildness is an incredibly tricky one, especially in a place like Britain which suffers so badly from ‘ecological tidiness disorder’ (as Benedict Macdonald puts it in Rebirding). The problem is that most of us have not made the connection between our tidy sterilised surroundings and the loss of nature. There is a lack of understanding that the majestically bare plains of Dartmoor or our rolling green fields mean an absence of life; and that you need all manner of species, including big ones, to ensure healthy ecosystems. I didn’t realise this for years. But once you know, you can’t stop wanting to bang the drum.

What are your biggest hopes and worst fears for the future of Wild Boar populations in Britain?

I want the planned, country-wide reintroduction of Wild Boar to become accepted both politically and societally. In the meantime, I hope that the few boar we do have are allowed to thrive. That means more oversight of people carrying out legal shooting of them on their land, and – in the case of the Forest of Dean population – better censusing methods to ensure they are not over-culled (though some culling will always be needed, as the boar currently lack other predators).

What am I most afraid of? That very soon, a disease called African Swine Fever (ASF) which burns through pig populations like wildfire will make its way into Britain. Since Brexit, border controls on pork imports have been so lax that experts think it’s only a matter of time before ASF reaches us. Forestry England is primed to wipe out every last boar in the Forest of Dean if the disease is ever detected in the population. And once they’re gone, it seems very unlikely that they would ever be reintroduced (legally or illegally) again. We will miss a miraculous chance to kickstart the landscape-scale restoration of nature in Britain.

Finally, what is occupying your time at the moment? Are there plans for further books in the pipeline?

I work full-time as a science communicator, which does narrow my research and writing windows! But I am currently working on a proposal for book number two. It’s intended to be something of an evolution of Groundbreakers, picking up a thread that often emerged during my research interviews with people, but which I couldn’t possibly have fitted into this first book…

Groundbreakers is available from our online bookstore.

Groundbreakers is available from our online bookstore.

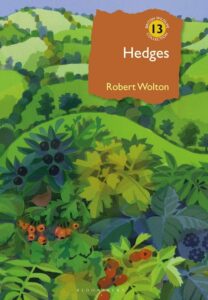

In Hedges, Robert Wolton brings together decades of research and personal experiences from his farm in Devon to explore the ecology, biology, nature conservation and wider environmental values of the hedges in the British Isles. Containing over 300 photographs and figures, this latest addition to the British Wildlife Collection offers a detailed commentary on hedges and their importance in our landscape.

In Hedges, Robert Wolton brings together decades of research and personal experiences from his farm in Devon to explore the ecology, biology, nature conservation and wider environmental values of the hedges in the British Isles. Containing over 300 photographs and figures, this latest addition to the British Wildlife Collection offers a detailed commentary on hedges and their importance in our landscape. Robert is an ecological consultant and writer specialising in the management of farmland and associated habitats for wildlife. He is a former hedgerow specialist for Natural England, the founder, chair, editor and lead author of the Devon Hedge Group, has been involved in Hedgelink since it began, and has written a number of reports and articles specialising in hedges.

Robert is an ecological consultant and writer specialising in the management of farmland and associated habitats for wildlife. He is a former hedgerow specialist for Natural England, the founder, chair, editor and lead author of the Devon Hedge Group, has been involved in Hedgelink since it began, and has written a number of reports and articles specialising in hedges.

What has stayed the same?

What has stayed the same?

Renowned rewilder Derek Gow has a dream: that one day we will see the return of the wolf to Britain. As Derek worked to reintroduce the beaver, he began to hear stories of the wolf. With increasing curiosity, Derek started to piece together fragments of information, stories and artefacts to reveal a shadowy creature that first walked proud through these lands and then was hunted to extinction as coexistence turned to fear, hatred and domination.

Renowned rewilder Derek Gow has a dream: that one day we will see the return of the wolf to Britain. As Derek worked to reintroduce the beaver, he began to hear stories of the wolf. With increasing curiosity, Derek started to piece together fragments of information, stories and artefacts to reveal a shadowy creature that first walked proud through these lands and then was hunted to extinction as coexistence turned to fear, hatred and domination.

Even in children’s tales, the wolf invariably represents a character of fear, violence and threat. Do you think these types of stories have a significant role to play in the development of our feelings towards wolves as adults?

Even in children’s tales, the wolf invariably represents a character of fear, violence and threat. Do you think these types of stories have a significant role to play in the development of our feelings towards wolves as adults?

Finally, what is occupying your time this winter? Do you have plans for more books?

Finally, what is occupying your time this winter? Do you have plans for more books?