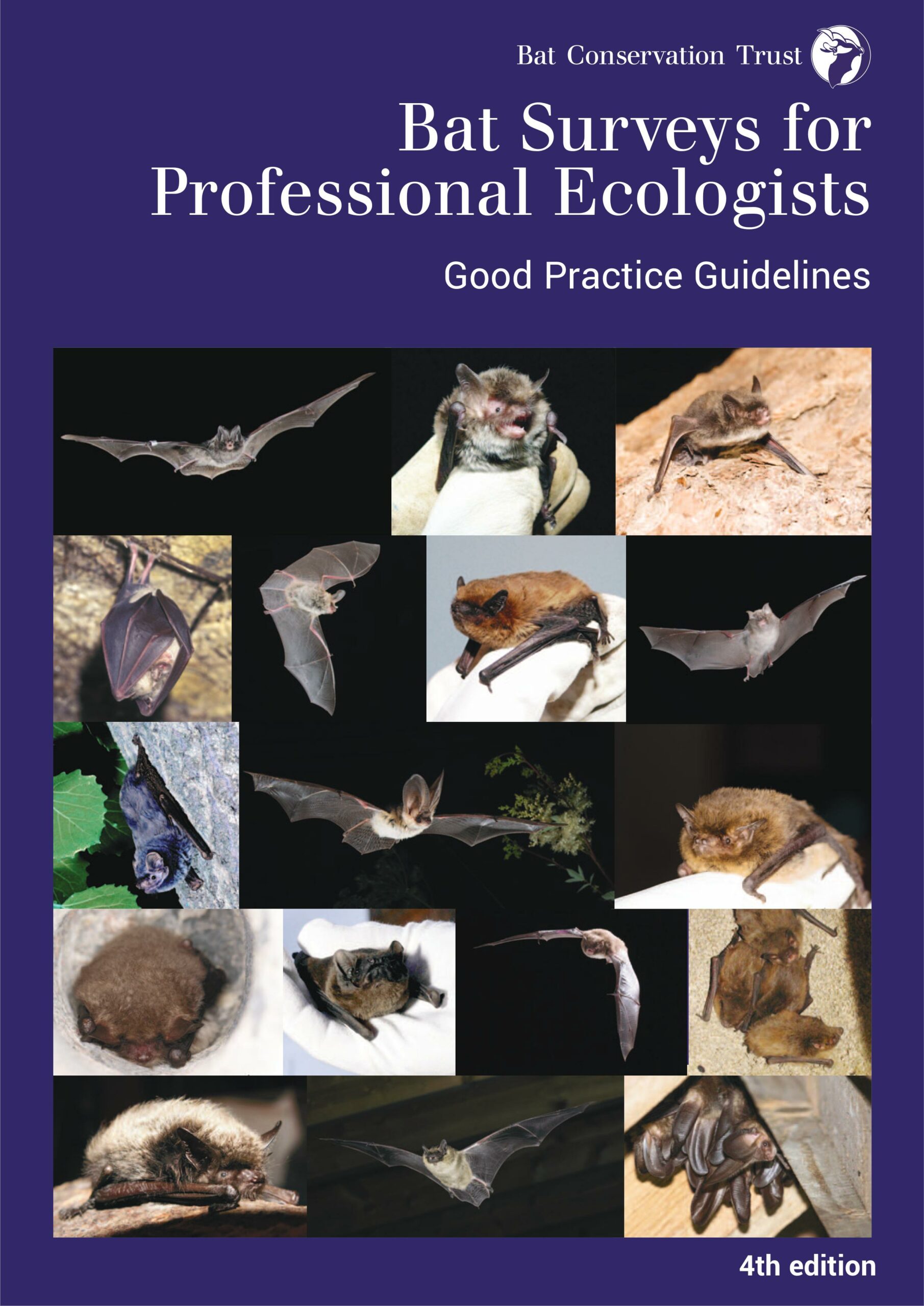

The 4th edition of Bat Surveys for Professional Ecologists: Good Practice Guidelines is the latest update of the Bat Conservation Trust (BCT) Guidelines and features new content on biosecurity, night-vision aids, tree surveys and auto-identification for bat sound analysis. Several key chapters have been expanded, and new tools, techniques and recommendations included. It is a key resource for professional ecologists carrying out surveys for development and planning.

Neil Middleton is a licensed bat worker and trainer. He is the Managing Director of BatAbility which offers bat-related and business skills development courses and training throughout the UK and Europe. He kindly agreed to take the time to write an article for us which will help ecologists and bat workers assess some of the key content and changes within the 4th edition of the Bat Survey Guidelines, and evaluate how this is likely to impact you, your colleagues and your business.

I have been asked to write this blog for NHBS regarding the recently published 4th edition of the BCT Bat Surveys for Professional Ecologists: Good Practice Guidelines. Straight away I feel I should say that, broadly speaking, we (BatAbility) are supportive of the overall spirit of intent that these new guidelines are seeking to achieve.

The contributors to the finished work and the editor of the final draft will have, I’m sure, had much debate about the final wording of the guidelines. It certainly cannot have been an easy task to come up with approaches that a broad range of experienced people, each with different backgrounds, were able to fully agree upon (or at least not disagree). In addition to which, these guidelines need to cater for all the component parts of the UK, where differences in legislation, planning, licensing etc. apply.

What follows are my thoughts on why you need to be up to speed with what’s happening. When I discuss some of the points you need to be aware of, it’s not that I am criticising or disagreeing with what has been produced, it is more that I am encouraging you to think about things that may not immediately be apparent when it comes to impacting (positively or negatively) upon your daily business operations.

Broadly speaking, these Good Practice Guidelines are what we all need to be referring to now for guidance and, barring any new properly released formal material direct from BCT (i.e. it doesn’t matter what someone says on a social media post or during a webinar) that either updates, changes or gives additional explanation to what is in the 4th edition, this is where we, as a community, are at. BCT have confirmed that a few changes to the text will be made by way of an amendment document and this, in conjunction with printed Q&A material resulting from BCT webinars (November 2023 and February 2024), will prove to be essential complimentary reading for everyone relying upon these guidelines during their day-to-day work.

Broadly speaking, these Good Practice Guidelines are what we all need to be referring to now for guidance and, barring any new properly released formal material direct from BCT (i.e. it doesn’t matter what someone says on a social media post or during a webinar) that either updates, changes or gives additional explanation to what is in the 4th edition, this is where we, as a community, are at. BCT have confirmed that a few changes to the text will be made by way of an amendment document and this, in conjunction with printed Q&A material resulting from BCT webinars (November 2023 and February 2024), will prove to be essential complimentary reading for everyone relying upon these guidelines during their day-to-day work.

At this stage, I feel that it is also important to say, and BCT have been very keen to emphasise this point (e.g. during their webinars on the subject), that the guidance is very clear about deviating from its approaches where specific cases and/or experienced, professional judgement suggests that a different approach can be taken for good reason, provided that it is fully disclosed and discussed within generated outputs (e.g. reports going to local planning departments). The material produced is described as ‘guidelines’ after all, and should not be used prescriptively when common sense, good scientific rationale or proportionality, as examples, suggests otherwise.

These updated guidelines were keenly awaited by bat workers for some time leading up to their publication.The driving force behind the update was thought mainly to be the integration of Night Vision Aids (NVAs) into our bat survey approach, as initially described within an Interim Guidance Note published in May 2022 and covered in this article on the BCT website.

I mention this for two reasons. Firstly, it’s what I feel almost everyone was genuinely expecting. Secondly, these revised guidelines don’t (as anticipated rightly or wrongly!) fully address some of the specific aspects of where the NVA debate is going to finally arrive. Regarding this aspect of bat work, the finer detail around this matter is now being tackled by a review panel, and BCT will inform us as/when they are in a position to do so. In the meantime, the Interim Guidance (2022) remains as an additional, essential point of referral. Having said that, within these new guidelines there are regular pointers, reminders and requirements that NVAs should be incorporated within survey design.

I mention this for two reasons. Firstly, it’s what I feel almost everyone was genuinely expecting. Secondly, these revised guidelines don’t (as anticipated rightly or wrongly!) fully address some of the specific aspects of where the NVA debate is going to finally arrive. Regarding this aspect of bat work, the finer detail around this matter is now being tackled by a review panel, and BCT will inform us as/when they are in a position to do so. In the meantime, the Interim Guidance (2022) remains as an additional, essential point of referral. Having said that, within these new guidelines there are regular pointers, reminders and requirements that NVAs should be incorporated within survey design.

So, why do we need to pay any attention to these new guidelines? If they are not telling us about the specifics of the NVA approach, then you may very well think that there’s not much value in getting your own copy and reading through, yet again, what was there before. Yes, you may very well think that. Yes, you would be very wrong.

There is so much in here that is going to make your life as a bat consultant different to how it was up until last year (2023). There are undoubtedly elephants potentially in some people’s rooms. But an hour after sunset when it’s too dark to see, some people may not be aware that elephants lurk (well not unless they have an NVA, and it’s pointing in the right direction). There are resourcing implications, cost implications, tendering implications, health and safety implications – there are all of these and more that you need to be aware of. And by implications I mean a mix of positives and negatives. It is a classic situation whereby in solving a range of issues and making clarifications on others, new issues and opportunities inevitably arise.

From a surveyor’s point of view, the dreaded dawn work is mostly redundant, although I feel there are still going to be occasions from a bat behaviour point of view, and from a health and safety point of view (e.g. working within busy town centre areas) where dawns could still occasionally be a better, or even a desirable approach. The guidelines certainly don’t say you should never do a dawn survey again, full stop.

From a business owner’s perspective there are matters that will need serious consideration and budgeting for. This could impact (again negatively or positively) upon your turnover, your approach to tendering, resourcing, the deployment of staff and equipment, as well as the careful balancing of your team’s time at their desks versus time in the field. All of this, of course, needs to be considered against the benefits to bat conservation. The challenge on the business model is not necessarily a bad thing, provided you are fore-armed and have seriously thought through how these changes impact upon your organisation.

From a business owner’s perspective there are matters that will need serious consideration and budgeting for. This could impact (again negatively or positively) upon your turnover, your approach to tendering, resourcing, the deployment of staff and equipment, as well as the careful balancing of your team’s time at their desks versus time in the field. All of this, of course, needs to be considered against the benefits to bat conservation. The challenge on the business model is not necessarily a bad thing, provided you are fore-armed and have seriously thought through how these changes impact upon your organisation.

Please don’t construe that I am not supportive of what these guidelines are seeking to achieve. In many respects, from a conservation perspective, I feel things have moved closer to where they should be. Balanced against this, however, I urge you to be aware that you need to get your head around the new approaches as a matter of urgency, and build into your day-to-day workings methods of adapting to the changes.

There is neither the time nor the space to cover it all here, and to do so would merely be to repeat what was contained in the guidelines in any case. What I am seeking to do is alert you to the fact that, despite how much you may have seen on social media etc. relating to the NVA debate, there are arguably equally as BIG matters contained within the new edition that don’t relate to the use of NVAs.

Here are some key points of where things have really changed, in my view:

- Dawn surveys are pretty much redundant, as we are now pressed to doing dusk surveys with NVAs. This is great from a work-life balance, but it also removes up to 50% of the previously available time slots on your survey calendar.

- NVAs are to be deployed on pretty much every emergence survey, covering the survey subject as fully as possible, with the associated implications for reviewing all that footage and storage of data. Video footage is much larger than the pure audio that you will have been accustomed to.

- A licenced bat worker is required to be present for any field work where a licensable situation could occur, no matter how likely or unlikely, be that structures or trees. Following the definite statements in the 4th edition, there is no longer any ‘wiggle room’ on this issue.

- Bats and Trees – aerial assessment (be that by ladder, rope or MEWP) is pretty much the desired approach, meaning that this will be a greater part of these jobs and, in conjunction with this, licensed bat worker(s) will need to be present.

- Due to the increased requirement for licensed bat workers to be present far more often than previously was the case, and the increase in tree climbing work where licensed bat worker(s) should also be used, there are resourcing implications that need to be considered when it comes to training in these areas. It is important to be aware that not every licensed bat worker within a business is either capable of or desires to climb trees. Also, in some business models, the licensed person/people are in more senior positions where their presence in the field conflicts directly with the role they are being asked to perform for the business (e.g. team management, client meetings, tendering, business process improvement). So, for some businesses, depending upon their current resources of licensed bat workers, there may need to be a rethink.

What I have described above is most definitely not the full suite of changes, but hopefully it’s enough to demonstrate that you need to get on top of what’s in there.

The key message is, if you haven’t already got yourself a copy and read it through in detail, then as a matter of urgency you should do so. Then you will be able to consider how you are going to achieve what is required.

The 4th edition of Bat Surveys for Professional Ecologists is available as a downloadable non-printable version direct from the BCT website.

Also available as hard copy from nhbs.com – remember to use your BCT membership number to get a 20% discount.

Broadly speaking, these Good Practice Guidelines are what we all need to be referring to now for guidance and, barring any new properly released formal material direct from BCT (i.e. it doesn’t matter what someone says on a social media post or during a webinar) that either updates, changes or gives additional explanation to what is in the 4th edition, this is where we, as a community, are at. BCT have confirmed that a few changes to the text will be made by way of an amendment document and this, in conjunction with printed Q&A material resulting from BCT webinars (November 2023 and February 2024), will prove to be essential complimentary reading for everyone relying upon these guidelines during their day-to-day work.

Broadly speaking, these Good Practice Guidelines are what we all need to be referring to now for guidance and, barring any new properly released formal material direct from BCT (i.e. it doesn’t matter what someone says on a social media post or during a webinar) that either updates, changes or gives additional explanation to what is in the 4th edition, this is where we, as a community, are at. BCT have confirmed that a few changes to the text will be made by way of an amendment document and this, in conjunction with printed Q&A material resulting from BCT webinars (November 2023 and February 2024), will prove to be essential complimentary reading for everyone relying upon these guidelines during their day-to-day work. I mention this for two reasons. Firstly, it’s what I feel almost everyone was genuinely expecting. Secondly, these revised guidelines don’t (as anticipated rightly or wrongly!) fully address some of the specific aspects of where the NVA debate is going to finally arrive. Regarding this aspect of bat work, the finer detail around this matter is now being tackled by a review panel, and BCT will inform us as/when they are in a position to do so. In the meantime, the Interim Guidance (2022) remains as an additional, essential point of referral. Having said that, within these new guidelines there are regular pointers, reminders and requirements that NVAs should be incorporated within survey design.

I mention this for two reasons. Firstly, it’s what I feel almost everyone was genuinely expecting. Secondly, these revised guidelines don’t (as anticipated rightly or wrongly!) fully address some of the specific aspects of where the NVA debate is going to finally arrive. Regarding this aspect of bat work, the finer detail around this matter is now being tackled by a review panel, and BCT will inform us as/when they are in a position to do so. In the meantime, the Interim Guidance (2022) remains as an additional, essential point of referral. Having said that, within these new guidelines there are regular pointers, reminders and requirements that NVAs should be incorporated within survey design. From a business owner’s perspective there are matters that will need serious consideration and budgeting for. This could impact (again negatively or positively) upon your turnover, your approach to tendering, resourcing, the deployment of staff and equipment, as well as the careful balancing of your team’s time at their desks versus time in the field. All of this, of course, needs to be considered against the benefits to bat conservation. The challenge on the business model is not necessarily a bad thing, provided you are fore-armed and have seriously thought through how these changes impact upon your organisation.

From a business owner’s perspective there are matters that will need serious consideration and budgeting for. This could impact (again negatively or positively) upon your turnover, your approach to tendering, resourcing, the deployment of staff and equipment, as well as the careful balancing of your team’s time at their desks versus time in the field. All of this, of course, needs to be considered against the benefits to bat conservation. The challenge on the business model is not necessarily a bad thing, provided you are fore-armed and have seriously thought through how these changes impact upon your organisation.

180ml Collecting Pot

180ml Collecting Pot

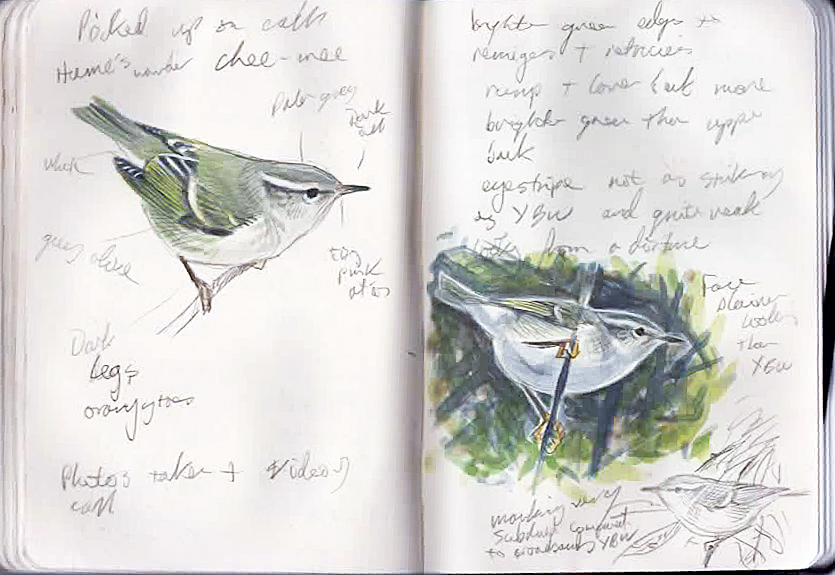

Mike Langman has been a full-time illustrator specialising in birds since 1992 and has published a total of 85 books

Mike Langman has been a full-time illustrator specialising in birds since 1992 and has published a total of 85 books