Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera, meaning ‘sheath-winged’. They get their name from the adaptation of their front wings which have formed tough protective cases called elytra. This gives them an armour-like appearance while protecting the delicate wings underneath.

As one of the most diverse groups across the world, there are over 400,000 species – more than 4,000 of these can be found in the UK. In this post we will look at some of Britain’s beetles, detailing their key features and where to find them.

Rose Chafer (Cetonia aurata)

Conservation status: Common

Distribution: Widespread across the UK, but scarce in number. Most common in southern England.

Identification: This large beetle is instantly recognisable by its iridescent emerald green carapace. Up to 2cm long, this broad beetle will often have white streaks across its wing case, which can occasionally appear purple or bronze in colour. The underside is covered in fine, pale hairs and there is an obvious ‘V’ shape on its back where the wing cases meet.

Where to find them: Grassland, woodland edges, scrub and farmland. Rose Chafers can also be found in towns and gardens, where they are considered a pest. You can find them between May and October when they can be spotted in sunny weather.

Cock Chafer (Melolontha melolontha)

Conservation status: Common

Distribution: Widely distributed across the UK, more common in the south of England.

Identification: The UK’s largest scarab beetle, the Cock Chafer can grow up to 4cm in length. It has rusty brown wing cases with a black body and brown legs. Its underside is covered in fine, pale hairs and it has a pointed tail. It has distinctively large, fan-like antennae that can be used to distinguish the sex – males have seven feathers and females have six.

Where to find them: Meadows, farmland, grassland, woodland, heath and moorland, and gardens from April to July. These insects are mostly seen after sunset, where they can be found near streetlights and bright windows.

Stag Beetle (Lucanus cervus)

Conservation status: A globally threatened species, the Stag Beetle is listed as a priority species in Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.

Distribution: Nationally scarce. This species is mainly found in south-east England. It is most abundant in the Thames Valley and Hampshire and is locally common in some areas of the south-west.

Identification: A spectacular insect, the Stag Beetle is recognised for its antler-like mandibles. Males can grow up to 8cm, while the females grow to 5cm and have smaller mandibles. Both have a shiny black head, thorax and legs with chestnut-coloured wing cases.

Where to find them: They can be found from mid-May to late July in woodland, hedgerows, parks and gardens. Although usually found on the ground, males can be seen in flight during sunset on hot summer evenings.

Lesser Stag Beetle (Dorcus paralellapipidus)

Conservation status: Common

Distribution: Found throughout England and Wales.

Identification: Smaller than their threatened cousins, the Lesser Stag Beetle grows up to 3cm in length and can be distinguished by smaller mandibles and knobbed antennae. Although similar in shape and colour, this species has a broad head and matt black wing cases.

Where to find them: Hedgerows, woods, farmland, grassland, towns and gardens from May to September. They can often be found basking in the sun on tree trunks and can be seen flying near bright lights at night.

Rosemary Beetle (Chrysolina americana)

Conservation status: Common

Distribution: Widespread in the UK, particularly in south-west England. Distribution is patchier in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Identification: A small, shiny beetle growing up to 1cm in length, the Rosemary Beetle is a striking metallic green with orange and purple stripes. The head and thorax are mostly green with some red markings, and the legs are a brown-red.

Where to find them: Rosemary Beetles are found year-round but are commonly spotted between April and September. The species is closely associated with Lavender, Thyme and Rosemary.

Wasp Beetle (Clytus arietis)

Conservation status: Common

Distribution: Widespread across the UK, less common in Scotland.

Identification: A narrow-bodied longhorn beetle, this species has a long, black body with yellow horizontal stripes. The Wasp Beetle has short brown antennae and brown legs.

Where to find them: Wasp Beetles can be found in farmland, woodland, hedgerows, parks and gardens between April and July.

Red Soldier Beetle (Rhagonycha fulva)

Conservation status: Common

Distribution: Widespread in the UK.

Identification: Growing up to 1cm in length, the Red Soldier Beetle is small and narrow. It has a rectangular body that is a vibrant orange red with black tips to the wing cases. Their orange legs are tipped with black feet and they have long antennae.

Where to find them: This species can be found from June to August, usually on open-structured flowers such as daisies and Cow Parsley, in grasslands, hedgerows, woodland, parks and gardens.

Red-headed Cardinal Beetle (Pyrochroa serraticornis)

Conservation status: Common

Distribution: Widespread in England and Wales.

Identification: A mid-sized beetle growing up to 2cm in length, the Red-headed Cardinal Beetle has a vibrant orange-red head and wing case. Its legs and antennae are black, the latter long and toothed.

Where to find them: Adults can be found in woodland, hedgerows, farmland, parks and gardens from May to July.

Devil’s Coach Horse Beetle (Staphylinus olens)

Conservation status: Common

Distribution: Widespread in the UK.

Identification: The Devil’s Coach Horse, easily recognised by its scorpion-like stance when threatened, is a medium-sized black beetle growing up to 3cm in length. It has large, powerful jaws and a long, thick abdomen. The body is covered in fine black hairs and the wing cases are very short.

Where to find them: Devil’s Coach Horse Beetles can be found from April to October in hedgerows, grassland, farmland and gardens. They require damp living conditions and are often found under stones and in compost heaps.

Violet Ground Beetle (Carabus violaceus)

Conservation status: Common

Distribution: Widespread in the UK.

Identification: Growing up to 3cm in length, the Violet Ground Beetle has a distinctive metallic violet colouring running along the edge of a black thorax and smooth wing cases.

Where to find them: Violet Ground Beetles can be found from March to October in woodland, grassland, moorland and urban areas. They are frequently found under logs and stones.

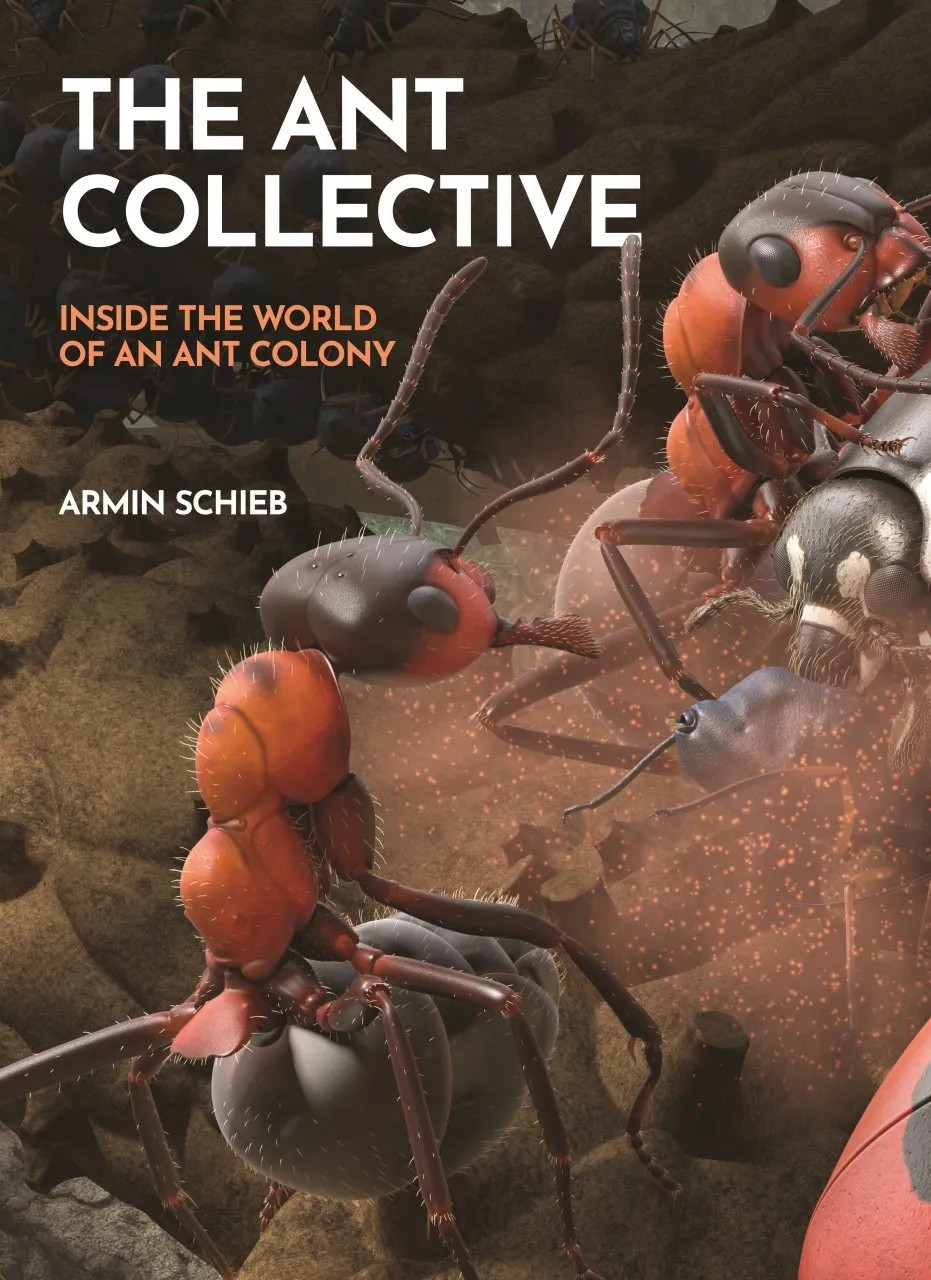

The promotional blurb for the book mentions it draws on the latest science though I was left somewhat confused when I finished it. Schieb is obviously not an entomologist but a graphic artist. There is no mention of the project having benefited from one or several entomologists acting as consultants to give the contents the once-over for scientific accuracy. There is no acknowledgements section where Schieb credits scientists for advice and input. There is not even a list of references or recommended reading included. Or is there? Since I do not have access to the German original I had to resort to some online sleuthing and found a preview on Amazon.de that includes the reference list on p. 126. This reveals that, yes, he has consulted books and scientific papers in both English and German, including that evergreen The Ants, an older edition of Insect Physiology and Biochemistry, and both specialist and general German books on forest insects. So, Schieb did his homework, Kosmos referenced it, but for some bizarre reason, Princeton simply omitted it, as the page between 125 and 127 is… blank! Did I just happen to receive a dud to review? Checking eight other copies at our warehouse confirmed that, no, this is a feature, not a bug. Hopefully, if there are future print runs, this is a detail that can be rectified, as it could easily leave readers with the wrong impression.

The promotional blurb for the book mentions it draws on the latest science though I was left somewhat confused when I finished it. Schieb is obviously not an entomologist but a graphic artist. There is no mention of the project having benefited from one or several entomologists acting as consultants to give the contents the once-over for scientific accuracy. There is no acknowledgements section where Schieb credits scientists for advice and input. There is not even a list of references or recommended reading included. Or is there? Since I do not have access to the German original I had to resort to some online sleuthing and found a preview on Amazon.de that includes the reference list on p. 126. This reveals that, yes, he has consulted books and scientific papers in both English and German, including that evergreen The Ants, an older edition of Insect Physiology and Biochemistry, and both specialist and general German books on forest insects. So, Schieb did his homework, Kosmos referenced it, but for some bizarre reason, Princeton simply omitted it, as the page between 125 and 127 is… blank! Did I just happen to receive a dud to review? Checking eight other copies at our warehouse confirmed that, no, this is a feature, not a bug. Hopefully, if there are future print runs, this is a detail that can be rectified, as it could easily leave readers with the wrong impression.