Haeckel’s Embryos: Images, Evolution, and Fraud

Haeckel’s Embryos: Images, Evolution, and Fraud

Written by Nick Hopwood

Published in hardback in June 2015 by Chicago University Press

Readers of our newsletter may remember Haeckel’s Embryos as my pick of 2015. A more in-depth review therefore seems in order.

The German naturalist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) is a figure I initially mostly knew from his beautiful Art Nouveau style drawings of animals and sea creatures, published as Kunstformen der Natur between 1899 and 1904. These perennially popular images have found their way into art books, an as yet unpublished pop-up book, and have of course not escaped the current colouring book craze.

Far more influential, however, are Haeckel’s contributions to the field of embryology and the now (in)famous images of grids showing embryos of humans and other backboned animals looking almost identical when just forming, and diverging in form during development. These images have become iconic, classics of textbooks right up to our current day, but are also some of the most fought-over images in the history of science, being the subject of three separate controversies, each one bigger still than the last one.

Haeckel’s Embryos is a study of how images of knowledge succeed and become the stuff of legends, or fail and fall by the wayside as forgotten side notes in history. Hopwood gives an incredibly detailed account of both the formation and the afterlife of Haeckel’s embryo drawings, and the accusations of fraud leveled at him. And you get a lot of book for your money, with 17 chapters running just over 300 pages and another 80 pages of notes and references. Measuring some 22 × 28 cm this is a large-format study that is richly illustrated (as befits a book of this type) with a large number of historical illustrations that have never appeared outside of their original context, a great many of which were dug out of the archives of the Ernst-Haeckel-Haus in Jena, Germany.

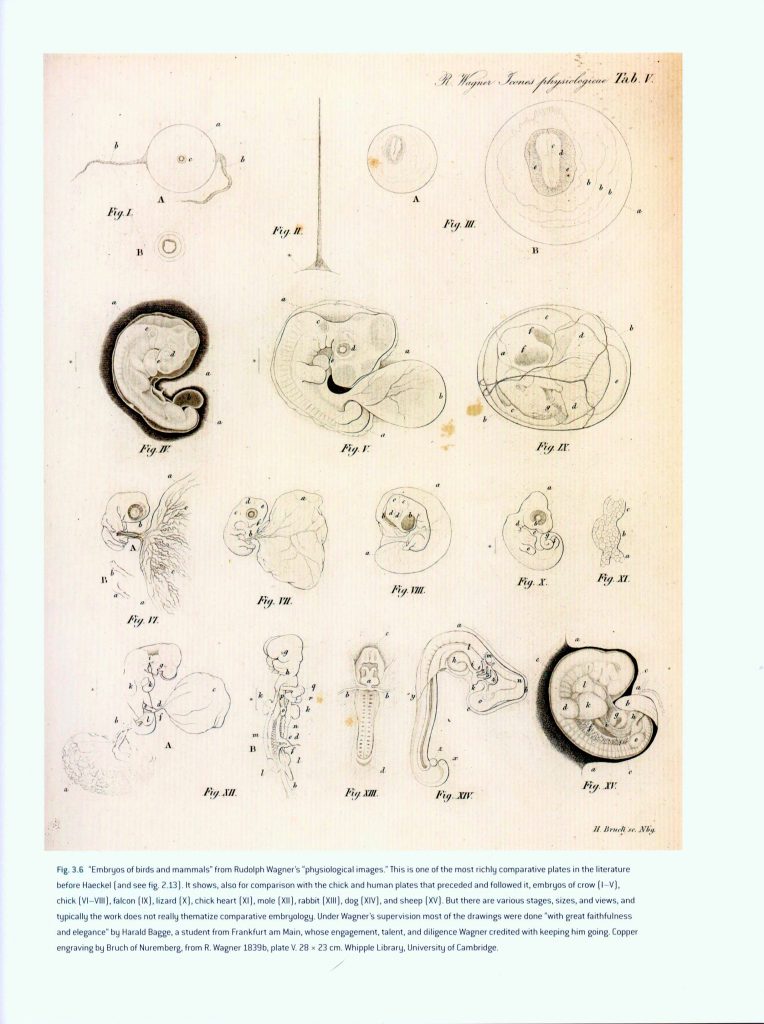

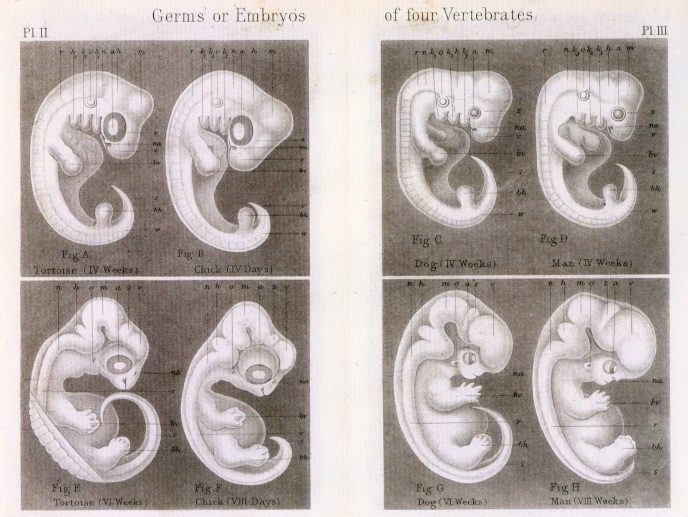

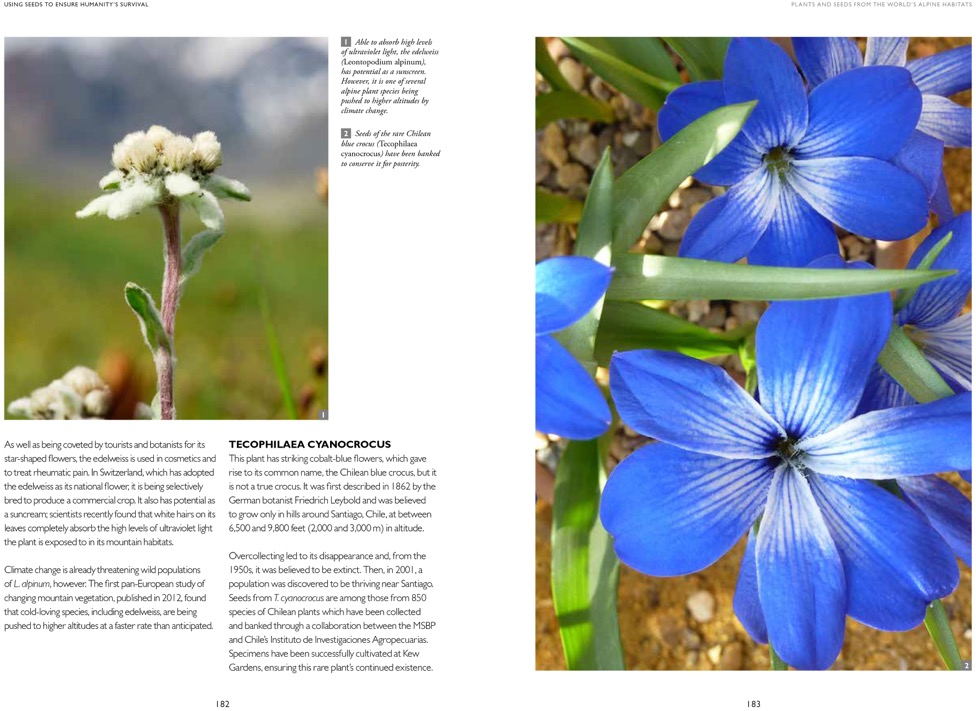

An example of embryological drawings circulating at the time

The book proceeds roughly chronologically, with the first three chapters setting the stage by reviewing the academic milieu into which Haeckel stepped, and the kinds of embryological drawings already circulating at the time. In chapter 5, then, Hopwood starts the investigation proper. He carefully reconstructs the making of the figures which were first published 1868 in Haeckel’s book Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte, and looks at each step from planning and drawing through to printing and publishing, mining Haeckel’s archives for both original drawings and correspondence with his publisher. This book went through eleven editions over more than forty years (1868-1909) and it is interesting to see how the famous grid developed gradually from initial pairs of drawings of two stages of dog, human, chick, and turtle embryos. The first “recognisable” grid (i.e. still circulating today ) didn’t emerge until inclusion in Haeckel’s more embryo-focused book Anthropogenie in 1874, which went through six editions until 1910.

Haeckel’s embryo grid during its development

His work immediately came in for criticism from fellow scientists, starting mid-1869 with the Swiss zoologist Ludwig Rütimeyer. Though no outright accusations of fraud and forgery were made, one of Rütimeyer’s concerns was Haeckel playing fast and loose with the public and with science by reusing the same woodcut illustration to represent early-stage pictures of dog, chicken and turtle. This was quickly rectified in the next edition, though Haeckel was slow to admit to his mistake. This barely caused a ripple on the pond, and Hopwood does a good job of making you realise why: this was an era in which discussions between scientists took place in either private correspondence, or in publications in obscure specialist literature, here the Archiv für Anthropologie, that was only circulated locally and will not have been read by more than a few hundreds of people. No, the first proper controversy did not take place until 1875, and saw Haeckel pitted against the Swiss anatomist Wilhelm His. One of the things they disagreed on was the similarity (Haeckel) or difference (His) of early embryos.

What is shocking is how Haeckel responded to this. I have never really had a good idea of the man’s character, and solely based on his beautiful artwork for Kunstformen der Natur have always thought of him benignly. Hopwood’s history reveals a rather different side to the man; he fashioned himself as a daring pioneer, here to enlighten the ignorant public (so much for humility), and his polemic responses to opponents bristle with arrogance, provocation and ad hominem attacks. He also refused to acknowledge mistakes, and countered charges of forgery – remarkably it was Haeckel himself who introduced this word in the discussion – as necessary deductions to fill in gaps, and as a logical consequence of presenting schematic figures. Although this soiled his reputation, the lack of a hostile consensus allowed Haeckel to draw ever more ambitious grids including more species. And the continued popularity of his work meant that the sheer number of books and later pamphlets in circulation made his pictures the most widely known and accessible in this era of print. It did spur his colleagues to set higher and higher standards for vertebrate embryology and push the field as a whole forward.

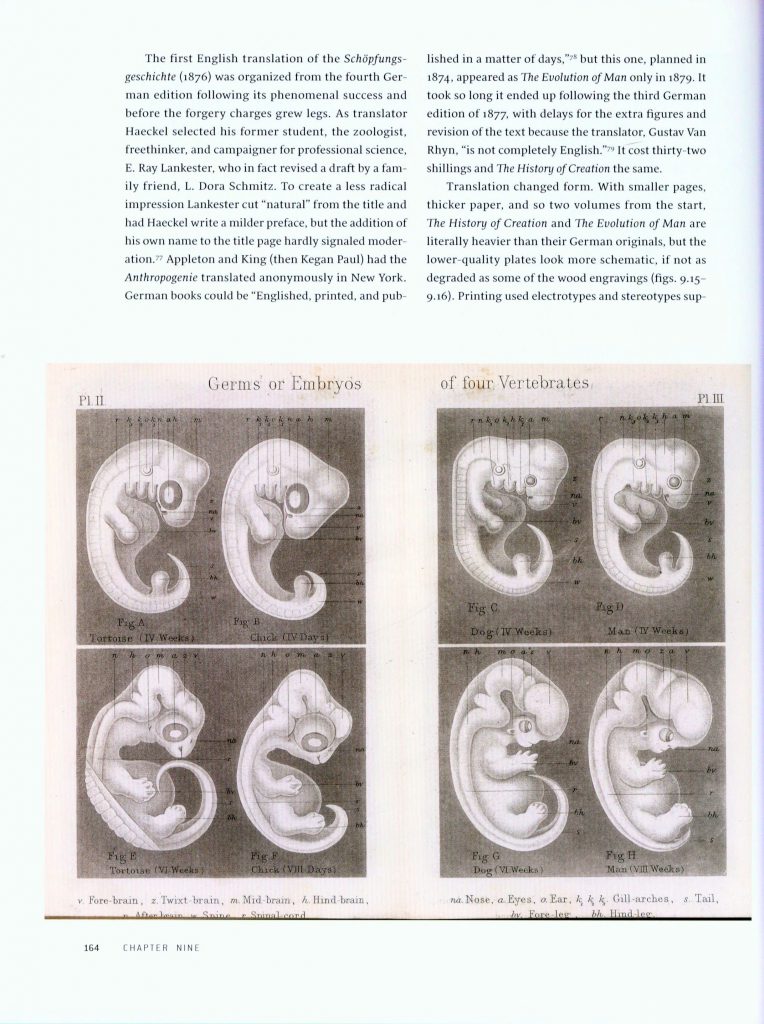

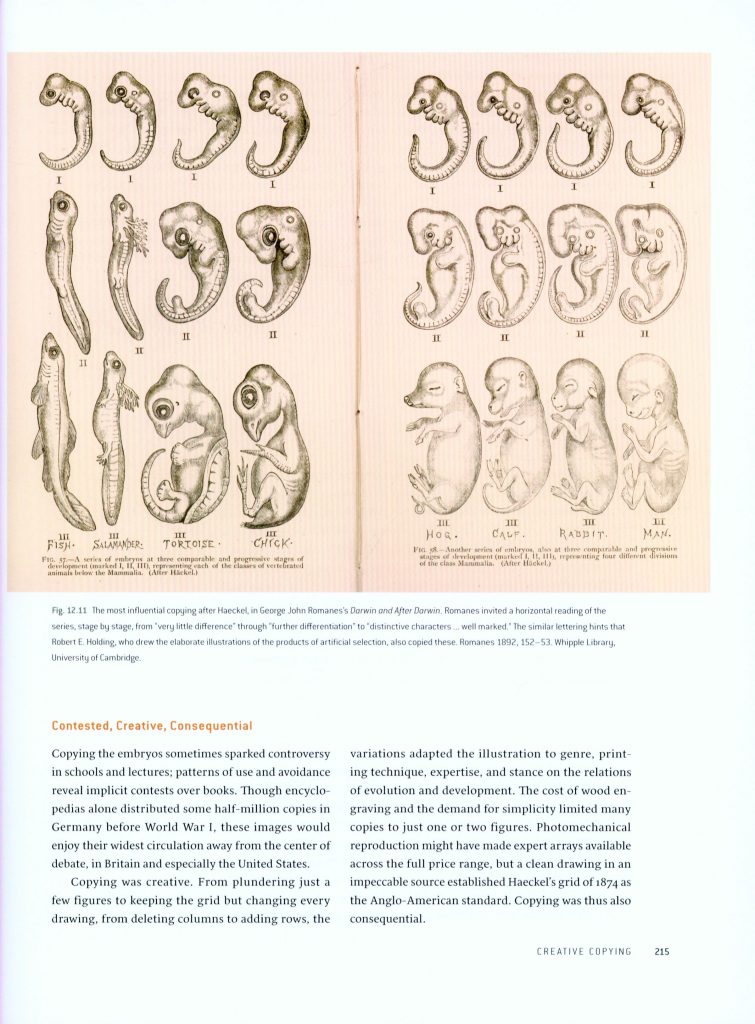

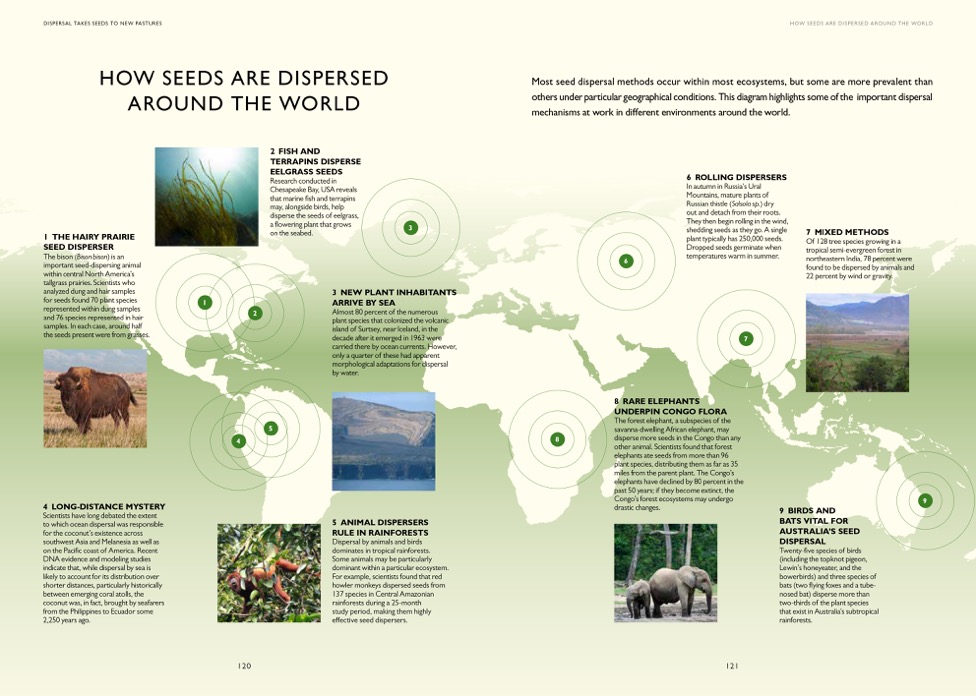

The next couple of chapters explore the 1870s to 1900s, discussing the expansion of Haeckel’s grids, how non-scientists encountered his work, how his work was reproduced and copied, and how critics kept the issue of forgery alive by repeating the allegations. These chapters make for especially revealing reading. Although Haeckel’s drawings were more available in Germany, the critics were also more numerous here, so copying was more extensive in Britain and the US. This also largely had to do with the available techniques for image reproduction at the time, which were both cumbersome and costly. And it was not until 1892 that George John Romanes reproduced the entire grid in his book Darwin and After Darwin. This reproduction also graces the dustjacket of Haeckel’s Embryos and to this day is the most reproduced and recognisable figure in Anglophone textbooks. But most copying was creative, with authors borrowing a few figures, deleting columns, adding rows, changing drawings, etc.

Romanes’s version of the grid

The second big controversy erupted around 1908-1910, when private scholar Arnold Brass became a spokesman for the freshly formed Kepler League, a club formed in response to a large public lecture that Haeckel gave. Following a lecture by Brass in which he attacked Haeckel, Haeckel returned the attack in a magazine, in response to which Brass privately published a slanderous pamphlet. The ensuing backing and forthing played out not in difficult books and serious periodicals, but in widely read newspapers. Brass’s pamphlet was so radical that it embarrassed even his own Kepler League. And it back-fired when morphologists recruited a large number of professors and museum directors to sign a declaration (“the declaration of the forty-six”), which, while not justifying Haeckel’s actions where his drawings were concerned, could see no motive for fraud. At the same time the declaration condemned Brass and the Kepler League for slandering such a respected biologist. This largely ended this controversy, partially in Haeckel’s favour. In his late life in Germany Haeckel was defended, forgiven, or reviled, depending on people’s political and religious inclinations. But the scientific community at large was more than happy to let bygones be bygones.

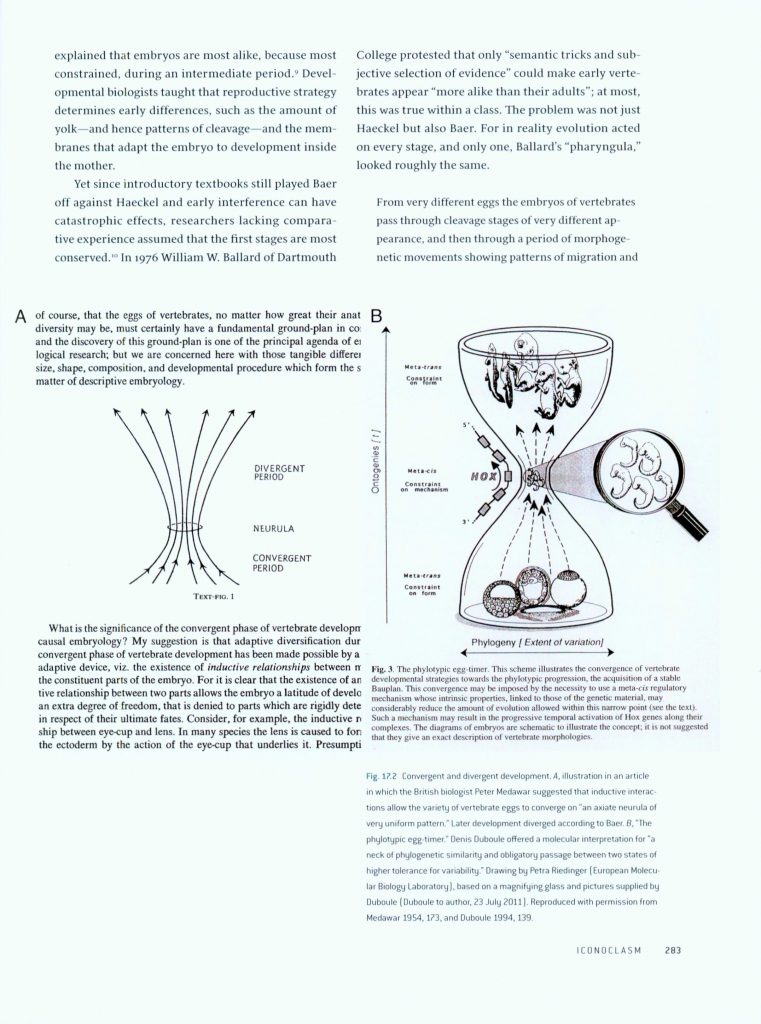

In the English-speaking world, in the meantime, too few of the exact allegations regarding his images were known in-depth, which meant the images still had a lease of life. And chapter 16 is a very interesting chapter telling the story of how the grid images survived into modern textbooks. Although faux-pas in postwar Germany, and only occasionally adopted in British schools, they were a relative staple in American textbooks. A combination of the higher profile of evolution as a subject in the American system in the early 20th century, and little knowledge of the forgery charges, meant the pictures could survive there. The rising and falling tides of anti-evolutionist sentiment did mean they were often modified and redacted, leaving out the human embryos. This further ensured their survival as it made them less radical. Another factor of influence was the inner workings of the textbook industry, where busy authors tended to copy each other or themselves rather than spend time to go back to the sources. Later on, the shift from authors to production teams meant that authors critical of Haeckel had less influence. In a further ironic twist, the Romanes drawing of Haeckel’s grid was often used while at the same time criticizing Haeckel in the accompanying body of the text. Interestingly, embryology textbooks long excluded the drawings, as their focus was not on evolution at the time. Experimental embryology as a field languished for decades until the 1960s when the field was reframed as developmental biology, although it took until the mid-1980s for Haeckel’s figures to be introduced to this discipline. By that time a new generation was only vaguely, or not at all, aware anymore of the accusations leveled at Haeckel. This knowledge was by now mostly limited to historians of biology, and even then many Anglophone historians were unaware. The few that weren’t did not realize how much the pictures were still in use (Hopwood counts himself among this group). This nicely undercuts the assumption that images and theories are linked so closely together that they live and die in unison. And this sets the stage for the third and final controversy surrounding these images.

An example of the embryo drawings surviving into contemporary books

The final two chapters detail the third and (for the moment) final controversy, which was set in motion by Michael Richardson (incidentally a lecturer of mine when I was studying at Leiden University in the 2000s). In several low-profile publications he criticized Haeckel’s drawings and, after comparing a wide range of vertebrate embryos, he concluded that “there is no highly conserved embryonic stage in the vertebrates”. To really get the spotlight on his findings however, he lured the press with a charge of forgery which was picked up by the Times, followed by Science and New Scientist. From here on outwards the story exploded and was rapidly exploited by creationists and the burgeoning Intelligent Design movement who threw around wild claims that “a primary pillar of evolution had finally been revealed as fraudulent” and, gasp, evolution was truly “a theory in crisis”. Richardson, embarrassed by the misappropriation of his publications and the misinformation that was being spread, started back-pedalling, and came under critique from colleagues in the field. He could have seen this one coming after all. But many came to his defense and even Stephen Jay Gould weighed in with a column in Natural History magazine, separating Richardsons’s “good science” from “careless reporting” and “media hype”. Richardson publisher a further long review, finding only “some evidence of doctoring”. Evo-devo aficionados debated the issue among themselves for a few more years, and the general consensus to come out of that was that on a fundamental level Haeckel was right, but he had taken artistic license in schematising his drawings. This was too late to affect mainstream perception though, and creationists, headed by the conservative think-tank The Discovery Institute, kept on adding fuel to the fire with books, public TV debates and, with the rise of the internet, websites and blogs. Ironically, recent research in developmental biology showed that embryological similarity between species at early stages isn’t just limited to morphology, but extends to gene expression patterns. In spite of this, Intelligent Design proponents have kept the focus on the most problematic images. Hopwood likens them to the iconoclasts of the Protestant Reformation, showing off beheaded statues as emblems of defeat. It is not in their best interest to remove all traces of these images, but rather to constantly exhibit them to vilify and condemn evolutionary theory and further their own agenda. Throughout all this circus the images were of course reproduced, copied and spread further and wider than ever before.

When I read about this book, I was hoping it would answer the question “Given what we now know about embryology, how do Haeckel’s images compare? What details did he change that gave rise to all these controversies?”. Seeing that this book claims to be a definitive history, and in pretty much all other respects is, I would have liked to see a concluding chapter laying out our current state of biological knowledge and see the old images compared to what we know now. Hopwood does reproduce some of the comparative images that Richardson published in his articles, but if you really want to get to the bottom of those questions, you will have to take a look there. This is understandable though: Hopwood is a historian, so the book focuses foremost on the history of these images, not so much on the biology behind it. And when he describes the third controversy he does mention the current consensus (Haeckel embellished but fundamentally makes a valid point) and the various opinions that now circulate. But a separate chapter laying out and summarizing just the biological facts then and now would for me have really completed the work, even at the risk of repeating what is already present diffusely throughout the book.

A lot more things are covered than I have mentioned here, and particular attention is paid to the religious and political milieu in Germany at the turn of the 19th century in which the first two controversies took place. A lot of this will be unfamiliar territory for today’s readers (it certainly was for me), and the book might have benefited from some side boxes introducing certain historical periods or schools of thought.

Those criticisms aside, in my opinion Hopwood offers readers an incredibly thorough and objective account of the complete 140+ year history of these controversial images. And I expect Haeckel’s Embryos will rapidly become the go-to work for both biologists and historians to understand their full, rich, and complex history.

Haeckel’s Embryos is available to order from NHBS.

This excellent field guide

This excellent field guide